Jack*, a yacht captain from Florida, became addicted to prescription opioids in the early 2000s. He had been born with flat feet and, starting from the age of 15, had several botched surgeries to reconstruct them. This left him in severe pain, for which he was prescribed Percocet by a ‘pill mill’ in Fort Lauderdale. This ruined his life. After graduating from high school, Jack used his parents’ money to pay for street drugs, not only opioids but also weed, ecstasy and acid.

An uncle, also a yacht captain, who had inspired Jack’s love of sailing, sent him to a rehab centre, but the draconian rule of routine and abstinence clashed with the adventurous nature of Jack’s work. He exhausted the two approved medical treatments for opioid withdrawal symptoms and cravings, both synthetic opioids that replaced a riskier drug with a safer one: methadone was ineffective, and buprenorphine worsened his dope sickness. Joining Narcotics Anonymous and going to therapy helped, but not enough.

In 2018, Jack drove up to Pensacola to visit his best friend who had discovered a drink called Vivazen. It came in small red bottles almost identical to the energy drink 5-Hour Energy, and was advertised as a herbal supplement derived from kratom, a tree in the coffee family indigenous to parts of Southeast Asia.

Of the many medicinal plants touted as opioid replacement therapies, kratom has become the most widely accessible, and the most controversial. At low doses it acts as a stimulant, much like tea, and at high doses it acts on the same receptors in the brain as opioids. You can find it in most urban head shops and some gas stations, with industry estimates placing the number of active American consumers as high as 15 million.

When the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) tried to make kratom illegal in 2016, advocates and researchers responded with the assertion that kratom use amounted to ‘harm reduction’, much like methadone and buprenorphine, opioids that are used because they reduce opioid-related mortality. Any of these have the potential for misuse, but harm reductionists would argue that they are far preferable to street opioids like heroin, which is increasingly being laced with fentanyl.

Kirsten Smith, an addiction researcher who studies kratom use at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, told me that, with adequate regulation, people benefitting from kratom should be listened to rather than punished. ‘We have to take people’s kratom stories seriously,’ she said. ‘Buprenorphine is an amazing treatment and we should make it more accessible, but so far it has done virtually nothing to slow down the opioid crisis.’

Harm reduction is a contested and evolving concept that was first used in the 1980s as a shorthand for practices to reduce the spread of hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS such as syringe exchange programmes. In general, it refers to public policies or practices that aim to reduce the negative consequences of drug use without necessarily reducing drug consumption. However, the term is also sometimes applied to any measure that could theoretically encourage socially divisive and risky behaviour, such as mandating seat belts or recommending teenagers be vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV).

Can the consumption of kratom, or herbal supplements in general, conducted almost exclusively without consultation with physicians or other drug addiction institutions in the US, be considered as harm reduction? For Jack, as for an extremely high percentage of opioid users in a 2020 survey study by Smith and her colleagues, kratom was effective in alleviating withdrawal symptoms (87 per cent) and reducing cravings (80 per cent) and pain (86 per cent).

‘When I took Vivazen,’ Jack said, ‘my dope sickness was gone.’ Within a year, he was completely off non-prescription opioids and back to sailing wealthy clients from San Marino around the Mediterranean.

‘Not a single one of my kratom patients told me it should be legal’

What started as two shots of Vivazen in the morning, however, quickly became five or six shots that he needed immediately when he got out of bed, followed by a bag of capsules containing another kratom extract called OPMS. ‘I was completely addicted,’ Jack told me. ‘Anyone who says kratom is not addictive has never tried it. I probably spent over $120 a day on kratom, way more than I had spent on oxies.’

Tucker Woods, a relation of Jack’s and the chief medical officer of a substance use centre in New York, caught wind of Jack’s new addiction. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Woods had never heard of kratom, which, from my interactions and interviews, appears true of most doctors who are not specialists in toxicology or addiction medicine. Yet, in 2021, Woods found that up to a 10th of his patients were suddenly struggling with dependence on the atypical opioid.

Many of the stories he encountered mirrored Jack’s. ‘I had one patient who had started out taking a bag of kratom capsules a day,’ Woods told me. ‘But he developed a tolerance and kept doubling his dose. When he saw me, he was taking over 80 capsules within a few minutes of waking up so that he wouldn’t go into withdrawal.’

Seizures, liver failure and cardiac arrest are rare complications of kratom use that almost exclusively occur in people taking the high doses found in extracts along with other illicit substances, although these extreme cases tend to occupy an outsized portion of media coverage about the plant. Woods sent Jack case reports of kratom patients needing liver transplants and articles about the first wrongful death lawsuits against companies selling extracts. ‘Not a single one of my kratom patients told me it should be legal,’ Woods said to me. ‘At the very least, we need to put a stop to the free-for-all.’

In the United States, dietary supplements are regulated more like food than like drugs. Not only does this allow companies to market their products as natural and replete with vague health benefits, but it also places them under the auspices of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. Under DSHEA, companies are not required to send the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information about ingredients in their products before selling them on the market. Thus, the FDA mostly relies on reactive, post-market surveillance methods, such as irregular factory inspections or adverse-event reporting from healthcare providers, to inform possible recalls.

In contrast, the regulation of ‘nutraceuticals’ in the European Union (EU) and in Asian-Pacific countries such as China are far more restrictive. The EU, for example, employs regulations to protect consumers from the potential health risks of low-quality products through the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which continuously evaluates and studies approved food supplements. For every approved product, the EFSA recommends a maximum and minimum level of daily consumption after verifying its nutritional content, which must be included on packaging with the label ‘food supplement’.

Krypton, a kratom product sold online, caused nine deaths in Sweden

As a result, American consumers have equal access to high-quality nutraceuticals, but they also have greater access to poor-quality ones. The benefits of proactive regulation in the latter case are clear. Placing a ban or a recall on a supplement is not an easy feat, especially for an under-resourced institution like the FDA. The Administration took seven years to ban the amphetamine derivative 1,3-dimethylamylamine, and another seven years to ban the Chinese medicinal herb ephedra, marketed as an athletic performance enhancement supplement, which generated more than 18,000 adverse-event reports and, in 2004, killed seven people in the US.

Furthermore, the FDA does not have a clear role in banning drugs; that’s more of the responsibility of the DEA, and so it’s unclear which agency has the mandate to recall supplements when consumers are harmed. In the crosshairs of this confusion was Krypton, a kratom product sold online that, between 2009 and 2010, caused nine deaths in Sweden, where kratom is now a controlled substance, because it was tainted with lethal doses of O-desmethyltramadol, a powerful opioid. In the past few years, in fact, there have been efforts at both the state and federal levels to remove the FDA’s aegis over kratom so that the primary kratom lobbying group, the American Kratom Association, can institute its own set of rules over quality control.

Physicians like Woods depend on the FDA to provide information and ‘black box’ warnings of potential serious side-effects to guide clinical decision-making, especially when it comes to off-label supplement use. However, as a result of DSHEA, the FDA lacks a robust infrastructure for reviewing the safety of products and creating clear delineations between indications and risks. This disincentivises researchers from investing time and money into studying their efficacy, and clinicians from even trying to make an educated assessment of risks and benefits, because most supplements fall outside their ‘scope of practice’.

This was Woods’s conundrum. There was not enough strong evidence that kratom extracts were safe in small amounts, and it was obvious that, in high amounts, they had addiction potential and could cause disastrous outcomes, even death. On the other hand, kratom seemed preferable to other non-prescription opioids, heroin in particular, and he met with patients who genuinely felt that kratom had helped them achieve remission when buprenorphine and methadone had not. Even if it led to dependence, Woods thought, self-medication had given his patients autonomy to make medical decisions in the context of whole lives spent struggling to find adequate relief in abusive and restrictive medical systems that had themselves played a major role in creating the opioid crisis in the first place. Telling a patient like Jack to simply stop taking kratom even though it allowed them to function was not likely to yield a trusting rapport, perhaps the most essential step to building an effective patient-doctor relationship.

Is there a middle ground, where providers can try to learn as much as possible about the supplements that their patients are taking while allowing some uncertainty to permeate future decisions? How can physicians promote patient wellbeing without exerting the disciplinary power characteristic of paternalistic medical systems that has thus far failed to curb overdose deaths from opioids?

In 2021, only 22 per cent of Americans with opioid addictions received effective care

This is where harm reduction narratives come into play. Many contend that, instead of supporting patients who self-medicate their addictions with unregulated supplements, we should focus on increasing the availability of approved treatments like buprenorphine and methadone.

The counterargument rests in the sheer difficulty of getting these medications. As a medical student, I was taught that the fundamental flaw of these medication-assisted treatments for addiction was the attached stigma and the structure of delivery. Buprenorphine, up until recently, required doctors who are not addiction specialists to obtain waivers from the government to prescribe it. Methadone is effective but siloed within opioid treatment programmes that are often not geographically accessible, and need daily follow-up and strict adherence from patients. For these reasons, in 2021, only 22 per cent of Americans with opioid addictions received effective care and, for patients who were women, Black, unemployed or living in rural communities, the percentage was much smaller.

Jack’s issue was not access, however. He came from an affluent, white family supportive of his hopeful recovery. He had been able to go down every avenue available, including medications, psychotherapy, inpatient rehab and Narcotics Anonymous. When all conventional options had been exhausted, was self-medication a valid mode of harm reduction?

Harm reduction is utilitarian. It doesn’t deem drugs inherently good or evil, and instead treats them as means to an end, leaving out beliefs about morality to crack down on rates of mortality. Jack’s own doctor knew about his kratom dependence and yet did not demand that he quit. Instead, the doctor did his best to inform Jack of what he knew about kratom and its potential interactions with other drugs Jack was taking while remaining nonjudgmental. This kind of relationship, while not strictly obeying the principle of ‘do no harm’, respects patient autonomy by carving out an environment where someone like Jack doesn’t feel the pressure to either break the therapeutic relationship or, even worse, continue the relationship while hiding their supplement use.

As a resident physician, I often hold back from enquiring deeply about a patient’s supplement use. Indeed, taking a standard medical history includes questions about smoking, use of alcohol and illicit substances – and over-the-counter supplements, as well. Most of the time, however, when a patient tells me that they take lion’s mane or ginkgo, I don’t say anything at all. Truthfully, I know almost nothing about even the most common herbal supplements and would, in all instances, prefer to educate my patient from a place of knowledge and research than a place of plain bias.

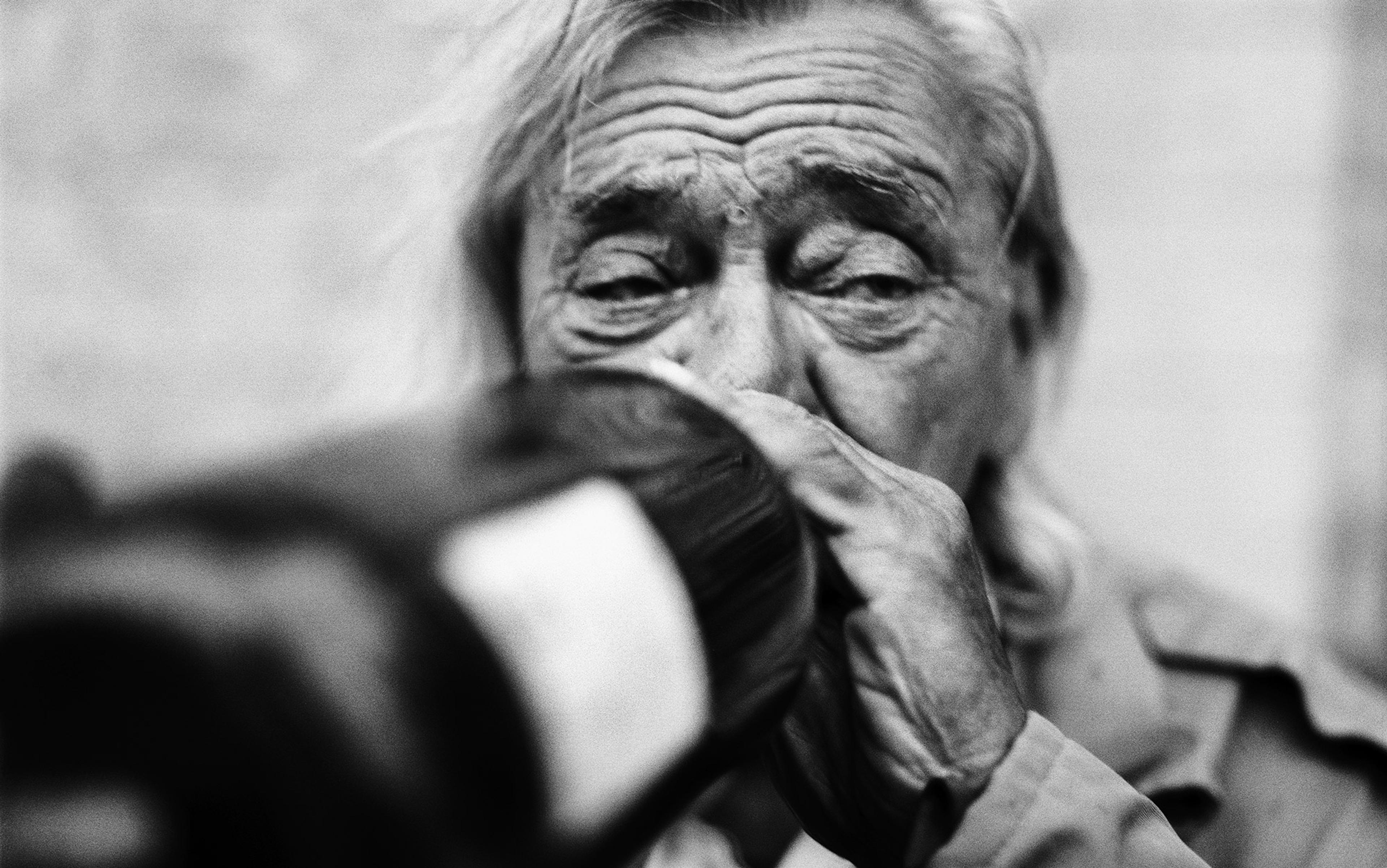

As Jack’s doses of self-administered kratom extracts increased, he found himself without the desire to eat

Partly, I’ve adopted a harm reduction approach to self-medication where I acknowledge that, in the majority of cases, a patient will continue to take their supplements regardless of what I say. And I would assert that trust and authority are qualities that are earned over time rather than demanded by the two letters after my name. It would be infinitely worse, I believe, for a patient to feel alienated from me because I’m sceptical of a supplement that they are benefitting from and then not want to return to see me.

And yet, this approach ultimately made things worse for Jack. As his doses of self-administered kratom extracts increased, he found himself without the desire to eat. In the fall of 2022, he weighed only 115 pounds. Depressed and weak, Jack was lured into trying crack cocaine by a guest at a yacht party, and he quickly developed an addiction to that as well. The combination of high-dose kratom and cocaine made his day-to-day life volatile and, over time, clients and family found him intolerable to be around. And, throughout this entire affair, Jack was still seeing his doctors.

How could Jack have proceeded? In a 2021 article for Harm Reduction Journal, a group of psychotherapists in Portland, Oregon, talking specifically about self-medication with psychedelics, argue that therapists should ‘adopt a non-coercive stance and help clients identify the risks and benefits of their behaviours’. Rather than assuming that a patient’s goal is abstinence, or that they are uncomfortable with having an open discussion about their supplement use, providers should openly solicit personal goals from the patient, and then have a discussion that centres around safety and education to guide the patient towards their desired life. After all, counselling a patient with incomplete information can also lead to harm.

In October 2022, on the advice of a friend who was also a therapist, Jack made a last-ditch escape to Cancún, Mexico, to undergo a week-long series of treatments with the psychedelic ibogaine, another controversial plant derivative that has shown potential in treating opioid addiction – but, unlike kratom, is illegal everywhere in the US and in most EU member states.

Jack was rail thin and, throughout his flight and the taxi ride to the resort clinic, he was wracked by chills. He could think about nothing besides finding a lighter and a pack of cigarettes. Arriving at the clinic felt like arriving in paradise. The resort staff included nurses and the doctor who administered him ibogaine, Felipe Malacara, a Mexican general practice physician who had almost two decades of experience with the drug. Jack had never met such kind people.

Days went by. Jack tripped for more than 12 hours as part of the treatment and then received several ‘booster’ doses when that had no effect. On the day before his flight back home, Jack stared at the sunlight reflecting off the calm surface of the resort’s pool and began to cry violently. He was enduring the worst withdrawals of his life and was about to return to Florida without a plan for the future.

Malacara happened to be walking by and tried to steady Jack’s tremoring, wailing body with a hand on the shoulder. ‘All the pain that you have inside of you,’ Malacara said to him, ‘just give it to me. Give it all to me, and I will do everything in my power to carry it for you so that you can live.’

Jack looked up and thought he saw the warm, assured, thickly bearded face of his uncle who was waiting for him on the other side with an invitation to dinner in his home. Malacara helped Jack to his feet, which no longer pained him. They hugged, and then Malacara left in silence. By New Year, Jack was back to sailing yachts.

* Some names have been anonymised for reasons of privacy.