Make a model of the world in your mind. Populate it, starting with the people you know. Build it up and furnish it. Draw in the lines that connect it all together, and the ones that divide it. Then roll it into the future. As you go forward, things disappear. Within a century or so, you and all the people around you have gone. As things go that are certain to go, they leave empty spaces. So do the uncertainties: the things that may not be things in the future, or may take different forms — vehicles, homes, ways of communicating, nations — that from here can be no more than a shimmer on the horizon. As one thing after another disappears, the scene fades to white. If you want a vision, you’ll have to project it yourself.

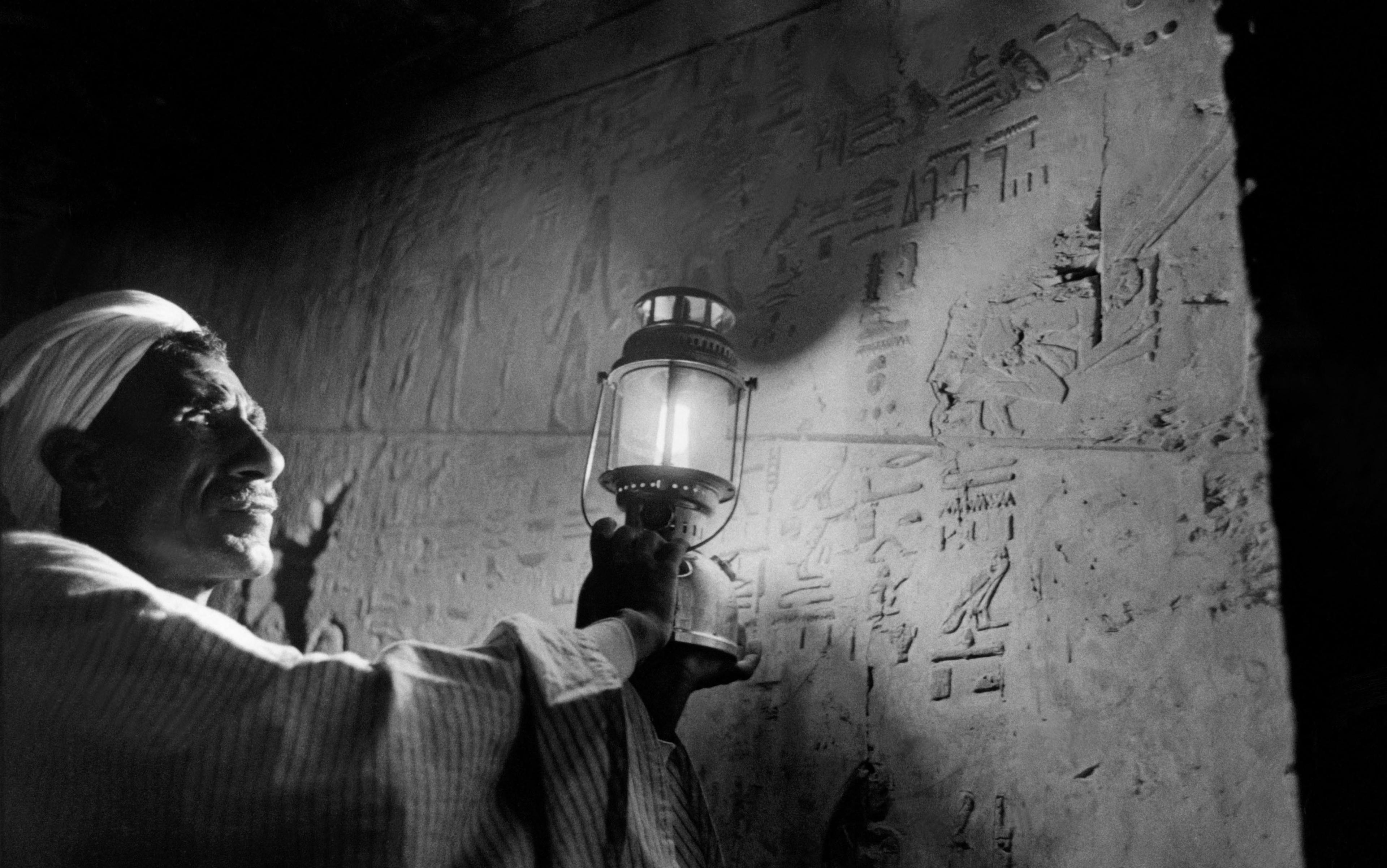

Occasionally, people take steps to counter the emptying by making things that will endure into the distant future. At a Hindu monastery in Hawaii, the Iraivan Temple is being built to last 1,000 years, using special concrete construction techniques. Carmelite monks plan to build a gothic monastery in the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming that will stand equally long. Norway’s National Library is expected to preserve documents for a 1,000-year span. The Long Now Foundation dwarfs these ambitions by an order of magnitude with its project to build a clock, inside a Nevada mountain, that will work for 10,000 years. And underground waste disposal plans for the Olkiluoto nuclear power plant in Finland have been reviewed for the next 250,000 years; the spent fuel will be held in copper canisters promised to last for millions of years.

An empty horizon matters. How can you care about something you can’t imagine?

A project can also reach out to the distant future even if it doesn’t have a figure placed on its lifespan. How many blueprints for great works, such as Gaudí’s Sagrada Família cathedral in Barcelona, or Haussmann’s Paris boulevards, or even Bazalgette’s London sewers, were drawn with the distant future in the corner of the architect’s or the engineer’s eye? The value of longevity is widely taken for granted: the 1,000-year targets for the Iraivan Temple, the new Mount Carmel monastery and the National Library of Norway are declared with little explanation as to why that particular round number has been chosen.

Instead, they play to intuition. A 1,000-year span has an intuitive symmetry for nations such as Norway that have a millennium of history behind them: it alludes to the depth of the nation’s heritage while suggesting that the country has at least as much history yet to come. For spiritual institutions, 1,000 years is short enough to be credible — England, for example, is dotted with Norman churches approaching their millennium — and long enough to refer to a timescale that extends beyond normal human capacities, thus pointing to the divine and the eternal.

People don’t generally reach out to the distant future for the future’s sake. Often what they chiefly want to reach is a contemporary audience. Going to extreme lengths to prevent vestigial nuclear hazards the other side of the next ice age is a demonstration of capacity, commitment to safety, and attention to detail. If this is what we’re doing for the distant future, it says to an uneasy public, you can be absolutely sure that we’ve got every possible near-term risk covered, too.

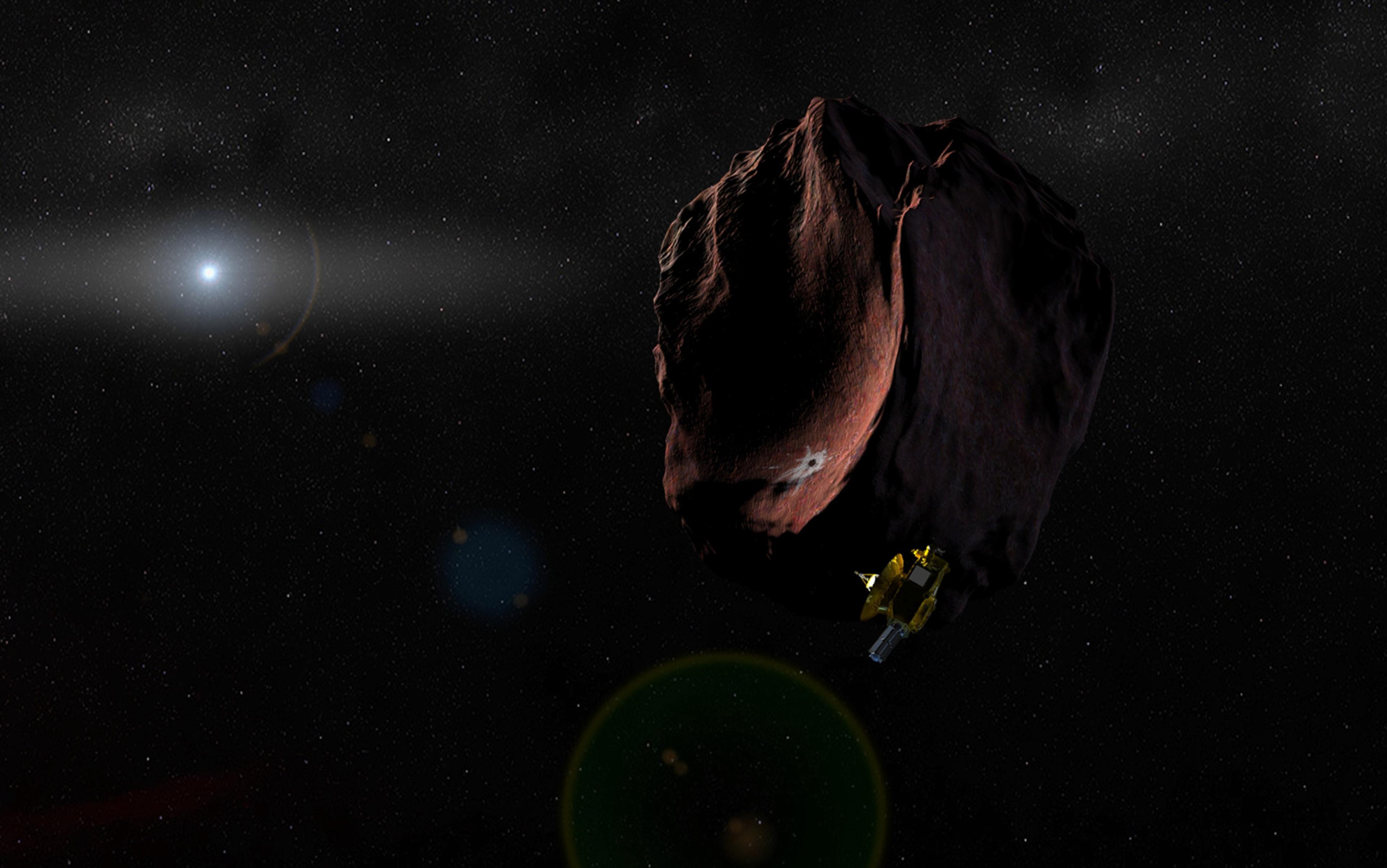

At the ultimate extreme, the Voyager space probes are carrying samplers of human culture, on golden disks, out of the solar system and on into infinite space. The notional beneficiaries are life forms that are not known to exist, from planets not yet detected, at distances the probes will not reach for millions of years. But the real beneficiaries were the people who reflected on our species and its place in the universe as they assembled the records and their content. The golden disks were mirrors of the culture that made them.

Any project with a distant time-horizon can be explained away as an exercise that invokes the future in the pursuit of immediate goals. But even if such a project is all about us, that doesn’t mean it’s not about the future too. The Long Now Foundation is an attempt to cultivate a consciousness that expands the horizons of the present. (Its name emerged from Brian Eno’s observation that in New York what people meant by ‘now’ was markedly shorter than what people meant by it in Europe.) By expanding ‘now’ to multi-millennial proportions, it makes us part of the future, and the future part of us.

A conceptual foundation that is building a 10,000-year clock may at first glance appear to have little in common with an Australian public highway operator and its new road bridge. But both have found ways to integrate the present with the distant future. Queensland Motorways chose a design lifespan of 300 years for its second Sir Leo Hielscher Bridge, rather than the 100 years typical for such projects, on the grounds that this would represent a better return for the community on the investment. It was worth spending public money now to benefit people in 300 years’ time, and it was justified because those people will be part of the community that exists today. The idea of ‘us’ that this practical, cost-conscious engineering project factored into its calculations is unconditionally generous, implicitly uniting everybody who resides in the area for the next 300 years at least, regardless of how they are related to each other, or whether they have contributed to the investment themselves.

A significant factor in the Queensland authorities’ calculations was that building a bridge to last for three centuries doesn’t cost three times as much as building it to last for a single century. One study has estimated that building a structure to last 300 years might be only 10 per cent more expensive than building it to last 30 years. Another was that a long design life might keep maintenance costs down.

These considerations are generally applicable. The prospects for reaching a distant time horizon will be improved if a long reach offers near-term benefits, and if the near-term costs of reaching out to the distant future are modest. In other words, the present and the future should have shared interests in the project, and the conflicts between the interests they do not share should be minor. The sense of common interest will be heightened if the benefactors and future beneficiaries are felt to be members of the same group, ‘us’ rather than ‘us and them’.

Any project that succeeds in establishing itself, whether by building a physical structure or by making an explicit commitment to deep posterity, will create a point on the empty horizon towards which people can gaze. It may be no more than a single pixel, but that’s better than a blank screen. Even a tenuous image of the distant future is of value at a geohistorical moment in which human actions may determine planetary conditions on a millennial scale. There are good scientific reasons to believe that if the world’s temperature goes up, it will stay up for the rest of the millennium and longer, while sea levels will continue to rise as the oceans slowly warm through and expand. We may well be on the verge of causing profound, irreversible disturbance to the earth’s systems. That places moral responsibilities on us at least to consider with a corresponding seriousness what our responsibilities to the future may be, and how we might make those responsibilities hold our attention.

That’s why an empty horizon matters. How can you care about something you can’t imagine? For all but the most rigorous moral philosophers, caring requires more than a logical reckoning of duty. People need visions of things they feel attached to, or find beautiful, or moving. They have to be able to imagine a future the failure of which to materialise would feel like a loss. Points on the horizon that help people to see something in the far future may help them feel connected to it. They may also encourage people to believe that there actually will be a future.

After you have systematically cleared the horizon of time and it has faded to white, imagine what is likely to happen if you let someone else get their hands on your vacant landscape. Like as not, they will strew apocalypse all over it: ruins, mutants, scattered bands armed against each other. People seem irresistibly drawn to the end of the world — but if they catch glimpses of a future in which spiritual edifices or ancient documents endure, they might be more inclined to help secure it, and less inclined towards nihilistic fantasy.

They don’t have to have a view of the far horizon in order to factor the distant future’s interests into their actions. The interests of their children and grandchildren will be more alive in their minds: serving them may well serve those of more distant generations, too. But at this possibly critical moment, when our imaginative sympathies need all the help they can get, it’s worth trying to focus a 1,000-year stare.