Every day I experience a ghost.

This ghost takes many different forms. Sometimes it’s a photograph uploaded to Facebook and stumbled upon at 2 or 3am, an old snapshot in which not all those photographed are still alive. At other times, the ghost is an email, a former acquaintance reaching out from beyond the grave of a friendship, attempting to channel our old selves. Occasionally, the ghost is just the buzzing of a fully-charged phone, oddly similar to a whisper. Always, the ghost is no ghost at all but rather a metaphor, a memory, a foothold between this world and one that no longer exists.

When unexpected, the ghost can startle, even frighten, and lately the rate at which they crop up has been quickening. ‘In a sense,’ wrote Leonard Woolf in his memoirs, in a quotation I think of with increasing frequency, ‘I have never become reconciled in London to the rhythm and the tempo of the whirring and the rushing cars.’ He was referring to his two centuries, a Victorian boyhood and the adulthood that followed; a life before and after the car, before and after speed. ‘And the tempo of living in 1886 was the tempo of the horses’ hooves, much more leisurely than it is today when it has become the tempo of the whirring and the whizzing wheels.’ The whirring and the whizzing years.

The pace of 2016 is even greater. The internet has done to the 21st century what the car, the telegraph, and electricity did to the 20th, compressing time and distance into a rush of too much information. Every morning I cradle my phone in bed, already overwhelmed by the ding of messages received, the swoosh of emails sent. The noise of productivity. The pace of life has changed since my childhood in the late 20th century, when I had only the slow melody of dial-up to contend with. It is quicker now, and with that pace comes the opportunity to be confronted daily with a new sense of time, one in which the past can be accessed in an instant and the dead are never really dead, just uploaded. These days I am, in a sense, haunted by the internet, and alongside that haunting there’s now a community online of people interested in more literal ghosts, with a fervour that hasn’t been seen since last century.

Ghosts aren’t real, not exactly. But what is not real is still often believed in, and what is called belief is nothing more than the existence, however brief, of uncertainty. When it comes to belief in the paranormal, most Americans are uncertain. Nearly one in five US adults – more than 18 per cent of people polled – claim, according to a 2009 Pew Research Center survey, to have seen ghosts, while a similar Gallup poll reveals that three out of four Americans believe in some form of the paranormal, be it ghosts or astrology or aliens or some other kind of supernatural phenomenon. On the other side of the Atlantic, a 2013 poll indicated that 52 per cent of British adults also believe in ghosts and spirits.

The numbers aren’t declining. Since the 1970s, the number of American adults who say they believe in ghosts has risen from one in 10 to one in three. At first glance, this growth seems irrational, considering that the rapid advance of technological progress was expected by many to make the world more rational and secular. But when websites such as the Wayback Machine archive websites for posterity and social media accounts linger on after our deaths, a new digital afterlife has been created, one that we can’t necessarily control. It’s this lack of control, this inability to resist the increasing speed and permanence of the digital life, that’s brought new vitality to paranormal belief. As technology grows more present, the ghost is this anxiety over the new impermanence writ large.

It has happened before. Two centuries ago, the Fox sisters dealt with the increasing speed of being human in a familiar way: they experienced a ghost.

Hydesville, New York; a dark evening in late March, blustery and cold. For weeks, the two youngest daughters of the Fox family – Margaretta, or ‘Maggie’, aged 14, and Kate, 11 – had reported hearing a series of noises echoing every night through the rooms and hallways of their childhood home. A tapping, is how they described it, or a rapping, like knuckles against their walls and windows. That evening – March 31, the night before April Fool’s – a neighbour came to investigate and with the girls and their mother, waited for the noises to begin.

One rap, two raps – I imagine it like popcorn popping. ‘I am certain this house is haunted,’ said Mrs Fox, according to the National Spiritualist Association of Churches in a rather dramatic account of the events, ‘and some unhappy presence is here. I feel it.’ Three raps, four raps. Kate, still only 11, remember, asked the supposed spirit to mimic her finger snaps, and it did. Mrs Fox then asked it to tap out the exact ages of all her children, which it did, including that of an infant who had died years earlier. How could it have known, Mrs. Fox and the neighbour wondered, frightened. As the night continued, the girls called the spirit Mr Splitfoot, as though it were the devil, and maybe, just maybe (thought the neighbour and Mrs Fox), it was.

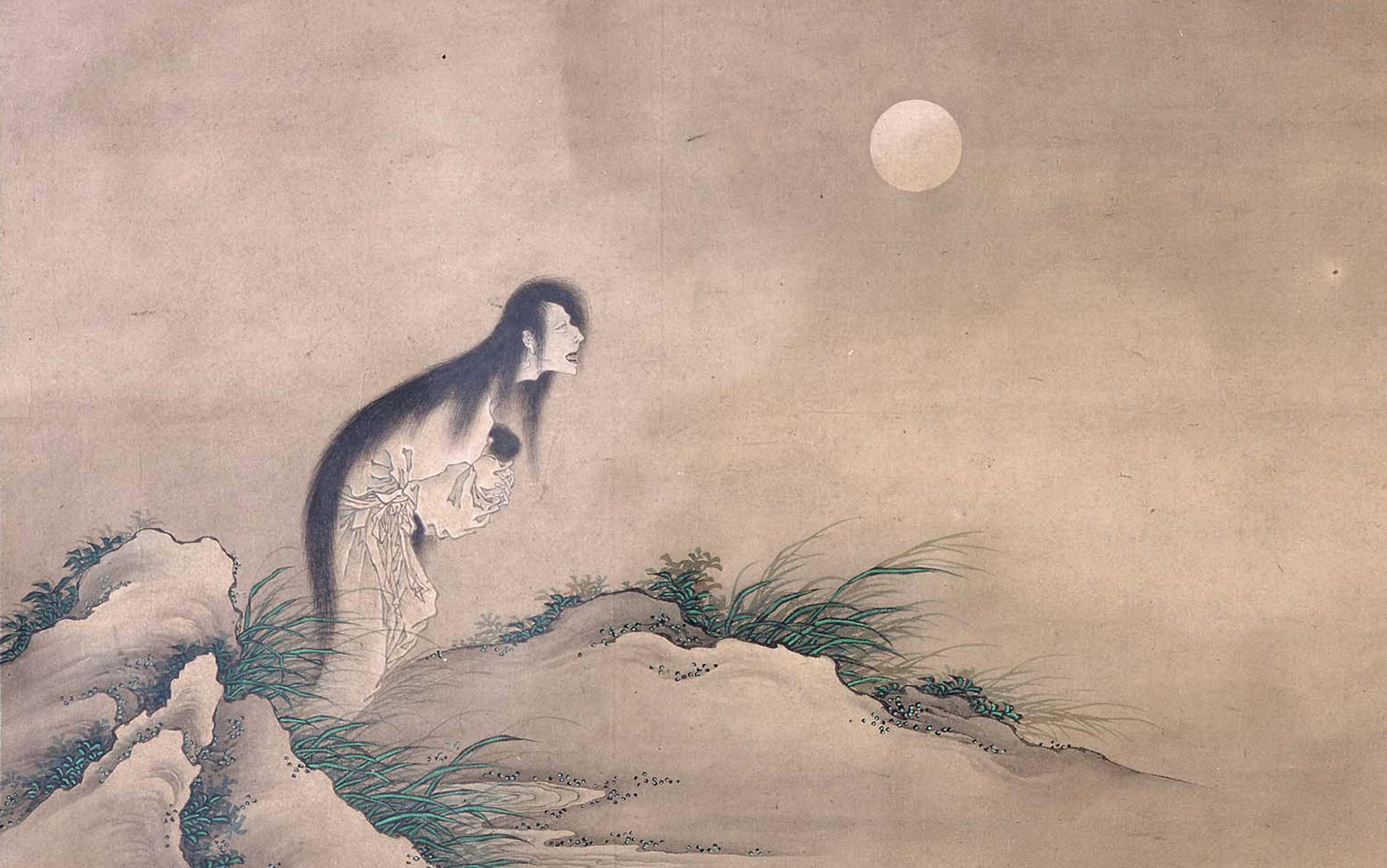

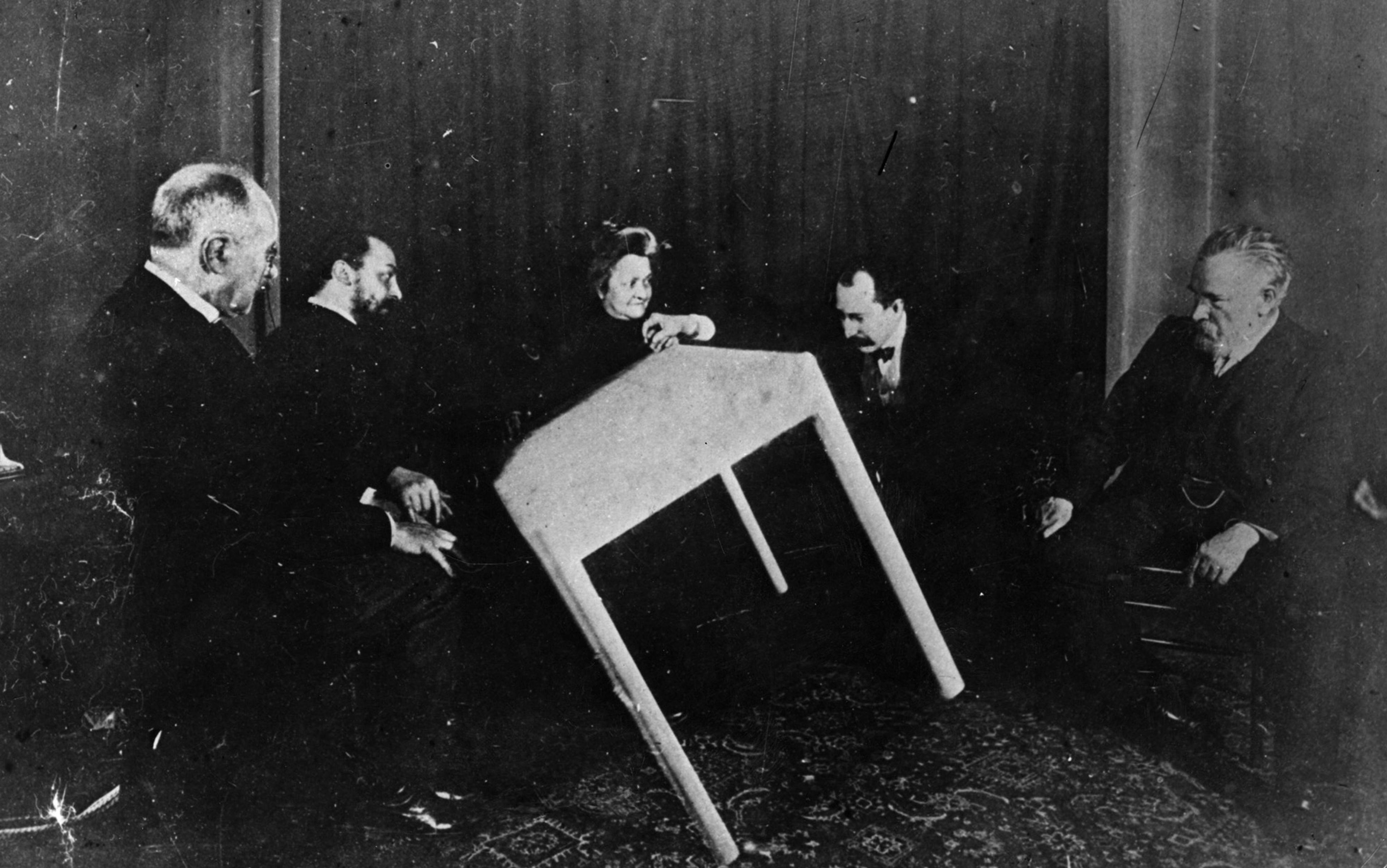

The Fox sisters would soon devise a corresponding system of raps and alphabet letters, allowing them to string together messages from ‘spirits’, and with this the organised Spiritualist movement, a popular folk religious movement that swept the United States and Europe from roughly 1848 to the 1920s, was born. Looking back at old photographs and mementos from the craze, it’s hard for contemporary eyes, so used to the complexities of Photoshop, to understand how anyone could have believed the crude and obviously doctored ‘evidence’ the mediums, spirit photographers, and hypnotists of the time used to trick their audiences.

The supposed ectoplasm spirits conjured up by the Scottish medium Helen Duncan, for example, were later exposed as simply dummies made of cheesecloth, rubber gloves, and magazine clippings. (In 1944, towards the end of her life, Duncan became the last person in Britain to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act of 1735.) The escape artist Harry Houdini, famous for his successful crusade of debunking mediums, remarked to the Los Angeles Times that ‘it takes a flimflammer to catch a flimflammer’, and most of Spiritualism’s most famous personalities – the Fox sisters included – were flimflammers.

It’s no coincidence that Spiritualism arrived alongside social progress and some of the 19th century’s greatest scientific theories – Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, for example – nor that the Fox sisters’ first tappings were heard during the same decade that witnessed the widespread adoption of the telegraph. This was the birth of modernity, when knowledge of human nature shifted and changed, and new technologies rendered possible what was once only magic: the wireless spread of information, the representation captured by the photograph, pictures that could move before one’s own eyes. ‘Spiritualism,’ writes the communications historian John Durham Peters in his Speaking Into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communications (1999), ‘explicitly modeled itself’ on the telegraph’s ability to receive remote messages.

Though the ambition of forging contact with the dead via mediums is ancient and widespread, Spiritualism’s birth as an organized practice dates to 1848, four years after the successful telegraphic link of Baltimore and Washington.

This is the thread holding all of these deceptions together: the want to believe. The desire to believe that another life exists beyond our own

So, too, did mediums such as the Fox sisters and their imitators successfully link the physical world to the fantasy of the immaterial. Also invented at this time was the Ouija board, with its spiral of letters and its planchard connecting human hand to ghost. Now anyone could be a medium, provided they had the proper accessories and as long as they believed.

Spirit photography was another, equally popular attempt to force the new technologies to accommodate old beliefs. The spirit photograph essentially relied on double exposure, a photographic technique that captures two different images in one photo, and was ‘discovered’ by the Boston-based engraver William Mumler in 1861. Mumler’s photos, like other spirit photographs of the time, are strange and deceptively mysterious: grim faces peer out from cloudy wisps that hover near the portrait subject’s shoulders or head, all culled from other photographs. In a famous Mumler portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln, a tall, stretched-out figure grips the former First Lady’s shoulders, a portrait of Abraham Lincoln soldered on to that of his widow. How dearly do her eyes want to believe that something would appear, that some vision of her late husband would exist beyond the assassination; Mumler had to have known this. He, too, was a fraud.

This is the thread holding all of these deceptions together: the want to believe. The desire to believe that another life exists beyond our own, or that our loved ones who left too soon will someday contact us again. Whenever a new device or a new form of communication is popularised, ghost stories quickly absorb it, turning the rational into the irrational, the haunted, and the human. Spiritualism did this to the telegraph and the photograph, while later in the post-war 1950s, increasingly sophisticated audio recording devices led to the rise of supposed ‘electronic voice phenomenon’, or EVP – ghost recordings, essentially. The message left on the answering machine by the grandmother who’s already dead, the haunted car that killed James Dean, the cursed videotape that’s trying to kill the print media reporter (and maybe it’s a metaphor for the entire newspaper business) – when new technologies scare us, we in turn make them scary.

And this is, as it turns out, is a wildly popular formula. In Paranormal Media: Audiences, Spirits, and Magic in Popular Culture (2010), by the media scholar Annette Hill, the British television executive Richard Woolfe tells us how he commissioned the ghost-hunting reality show Most Haunted after buying a copy of every women’s magazine he could find and realising they all had one thing in common: stories of the paranormal.

In 2012, an Illinois family experienced strange appearances and disappearances in the grounds of their suburban home, as flowers, food and sand that had not been ordered began arriving, like unwanted offerings, on their doorstep. Invisible fingers traced their email inboxes and their online bills, one by one, as each of their private accounts was attacked and compromised. Though the Straters were in fact the victims of human hackers, what’s interesting about the language that Fusion used when reporting their story in October 2015 is that it was the language of an exorcism: ‘poltergeist’, ‘haunted’, a ‘digital ghost story’. Somehow, even when the culprits are flesh and blood, our anxiety concerning the speed and shape of machines and their owners’ sudden, mysterious lack of control leaks over, colouring our perceptions. The internet is nothing more than a transmitter of ghosts and their longings.

It’s only a fork in the road, after all, that separates the ghost story from science fiction, where hackers-gone-mad and computers acting of their own accord have long been familiar tropes. Also a trope: the cyborg, that Frankenstein mishmash of human and machine. Even death, which is so animal, is now taking on a strange cyborg flair, as the obituary goes digital and the information we upload online about ourselves becomes difficult, even impossible, to access.

Death has compelled social media platforms to devise policies concerning their users’ accounts, with the strange consequence that is the memorial page. Facebook’s official policy is to turn an account into such a memorial, where ‘people can save and share their memories of those who’ve passed’. Twitter will deactivate a deceased user’s account following a loved one’s official request, while YouTube and Gmail will allow friends and family to access the deceased’s accounts. Yahoo’s email users, though, are out of luck: in 2005, a Michigan man named John Ellsworth had to sue the company for the release of his deceased son’s emails. Apple isn’t innocent, either: a 72-year-old Canadian widow is currently battling with the company following its refusal to release her dead husband’s Apple account login details to her. It’s now possible to treat one’s social media feed as something akin to a digital graveyard, or a 21st century version of that medieval maxim memento mori: “Remember, you will die.”

Then there are grim forums like MyDeathSpace, its name a play on the early social networking site MySpace and its purpose the pooling of dead users’ social media accounts. The site first gained attention in 2006, shortly after its invention, and was heavily criticised; today, it still exists, and its forum members have a special predilection for compiling the profiles of the murdered, the suicidal, and overdose victims. While humans have certainly been morbid concerning other people’s deaths for centuries – public hangings come to mind – sites like MyDeathSpace have a peculiar mirror-like effect: the more you read it, the more you start speculating about your own death, and how it will be perceived. ‘My death space, as they call it,’ goes a line in the Bruce Bond poem named after the website, ‘as though it’s me / who died. A life, we know, is complex. / But death is simple. A place to talk shit, / to license grief, or barring that, kill it.’ For all of their voyeurism, speculation, and occasional, disturbing glee, sites like MyDeathSpace also have a distancing effect: yes, someone died. But it’s only real on a computer screen.

Some of us are coping with this nihilism in a familiar way: online, people are telling each other stories of their ghost experiences.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter what is true or false, supernatural or true crime. What all of the stories have in common is the intent to provoke one specific emotion: fear

‘I woke up in the middle of the night,’ goes one, ‘with the weirdest feeling that someone was watching me…’ ‘My father said he’s frequently seen a woman in a white dress at the top of our stairs,’ another might begin. ‘My mum used to clean house, until she didn’t.’ ‘The patient was at the top of the bed and looked at me and said, “Don’t let them take me!”’ The tales are familiar: all the storytellers fear that their peers might consider them crazy, but they have to confess what they may or may not have seen. Mostly, they’re believed. To all ghost stories there is a pattern: someone sees something and, for at least a moment, believes.

With the rise of the internet has come a popular surge in people looking to be freaked out. The genre of stories they created, known as ‘creepypasta’ – a perversion of ‘copy paste’, the keyboard commands – take as their material the frightening, the inexplicable, and the weird. Most are assuredly made up – Slender Man, created by members of the Something Awful forum, is the most prominent example, but other famous stories include things like Ted’s Caving Page, an Angelfire website straight out of the 1990s about a spelunking trip gone wrong – but others are simple confessions, a recounting of something ‘off’ or weird that happened to the writer. Often, they draw inspiration from aspects of millennial childhoods, like a series on haunted Pokémon games that’s popular on the main creepypasta wiki.

Other sites, like the occasional paranormal-themed question on Ask Reddit, contend that their answers are true, but who knows? NoSleep, a Reddit community dedicated to what it terms ‘original horror stories’, displays the mantra, ‘Everything is true here, even when it’s not’. In the end, it doesn’t really matter what is true or false, supernatural or true crime. What all of the stories have in common is the intent to provoke one specific emotion: fear.

To be frightened, after all, is to reaffirm an essential mortality. It’s to feel the physicality of the human heart beating, human blood rushing; it’s the adrenaline that reminds us that we’re bone and breath and brain. Not every creepypasta reader believes in ghosts, but many of us need them in order to remind ourselves what it’s like to be alive. When death is increasingly digital, and when the daily round is so connected to new technologies, something about life can feel very foggy and distant. So we read a scary story, snap our laptops shut in fear, and dive under the covers, human once more, until morning comes and the tempo speeds up again.

There is no such thing as a ghost. There are only memories, and the stories of them that we tell. Still, sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night, and swear I see a phantom. When I blink, I realise that it’s only the fickle light of my computer screen, unearthly blue and glowing.