Close your eyes, and envision a glowing crystal suspended in infinite space. Now breathe in slowly, counting backwards from 10. Energy pulses along the interstices of the crystal. Exhale, and imagine a second crystal, precisely like the first – then a dozen, a hundred, 100,000 crystals multiplying into an infinite void. And 100,000 dream catchers. And semiprecious stones inscribed with chakras. And ‘Coexist’ bumper stickers, Alex Grey posters, Tibetan prayer flags, wellness magnets, and ionising Himalayan salt lamps.

Now open your eyes and imagine how much they all cost.

It’s easy to scoff at the totemic kitsch of the New Age movement. But it’s impossible to deny its importance, both as an economic force and as a cultural template, a way of approaching the world. The New Age is a powerful mixture of mass-market mysticism and idealistic yearning. It’s also, arguably, our era’s most popular ex novo spiritual movement, winning adherents with a blend of ancient wisdom traditions, post-Enlightenment mysticism and contemporary globalisation that is as nebulous as it is heady.

It’s worth noting at the outset: New Age is not so much a discrete collection of beliefs as it is a Venn diagram (or a mandala, if you like) of intersecting interests, objectives and motifs. The New Age ‘movement’ is not a single movement at all. The term contains multitudes.

Arguably, the aspect of New Age that is easiest to pin down is also the most superficial: the look. The term conjures visions of chakra charts, indigo auras, psychedelic paintings of bodies radiating energy, crystals, candles, ambient music and dream catchers. One can guess with reasonable certainty that the crowd at a New Age gathering – a solstice ceremony in Golden Gate Park, say – will display a collective taste for dreadlocks, aromatherapy, South Asian or Andean textiles and accoutrements such as utility kilts, gnarled oaken staffs and coin pouches that wouldn’t look out of place at a Renaissance Fair. The aesthetic is one of unabashed pastiche.

So, too, are the beliefs undergirding it. Even scholars who have spent years studying the New Age movement disagree about what precisely it is. For the sociologist David J Hess of Vanderbilt University, ‘New Agers’ are religious seekers ‘who accept the paranormal in the context of a broader quest for spiritual knowledge’. The anthropologists Ruth Prince and the late David Riches of the University of St Andrews, who conducted a study of Neo-Druids at Glastonbury in the late 1990s, framed the New Age as a form of social organisation that recreates hunter-gatherer patterns of life and seeks ‘to rethink in terms of first principles the very nature of human society’. In 1994, Christoph Bochinger, now a professor of religion at the University of Bayreuth in Germany, wrote a monograph on the New Age movement, despite arguing that the term is in fact an ‘invention of the media’. Meanwhile, many in the natural sciences and the skeptic community use ‘New Agers’ indiscriminately as a blanket term for contemporary snake-oil salesmen who profit from a recent turn away from Western medicine.

I would argue that if there is one thread that binds together the various New Age movements, it is that they represent a resurgence of magical beliefs in a modern world supposedly stripped of them.

In his now-classic book Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971), the Oxford University historian Keith Thomas framed religion and magic as antagonistic social forces. In his view, when early modern Protestant and Catholic religious leaders persecuted witches, they were effectively trying to eliminate their competition as explainers of the unexplainable. In this, they largely succeeded. Because representatives of institutionalised religion had ‘all the resources of organised political power’ on their side, they were able to force magical practitioners into the shadows: ‘Magic had no Church, no communion symbolising the unity of believers,’ Thomas writes. ‘The official religion of industrial England was one from which the primitive “magical” elements had been very largely shorn.’ In the process of this rejection of supernatural explanations, post-Enlightenment religious beliefs became increasingly standardised and grounded in the concept of natural laws that it was within the ability of human minds to fathom.

As the German sociologist Max Weber put it 100 years ago, a distinguishing feature of modernity is ‘the disenchantment of the world’. For Weber and the countless historians and social scientists who have taken his theories as starting points, the rise of modern science and ‘scientifically oriented technology’ replaced the ‘mysterious incalculable forces’ that pervaded pre‑modern worldviews.

But what if Weber and Thomas were wrong? Ironically, at precisely the time when Thomas was anatomising the death of magic in the 1970s, bohemian mystics in places such as California and London were reviving it. Perhaps the sole characteristic shared by the modern-day inheritors of the 1960s and ’70s counterculture – from Neo-Druids in Stonehenge and eco-feminist witches in San Francisco to practitioners of alternative medicine, Indigo children and aura readers – is this desire to ‘re-enchant’ the world.

Yet if New Agers seek to recapture a pre‑modern belief in ‘mysterious incalculable forces’, they do so using all the tools of contemporary technology and the networks of modern globalisation. It’s not coincidental that the earliest calls for a ‘New Age’ of spiritual awakening coincided with the Industrial Revolution. Or that the triumph of a more formalised and commoditised New Age movement in the second half of the 20th century converged with the rise of television infomercials, books on tape, local‑access cable channels, and the early internet. Today, New Age aesthetics and modes of thought have filtered into mainstream society, influencing everything from the rise of alternative medicine (a $34 billion industry, by one recent estimate) to the triumph of yoga in the suburbs.

Meanwhile, formal religious affiliation is on the decline in the Western world, but this rejection of traditional organised religion does not imply a rejection of spirituality. Instead, it has created a vacuum in which the eclecticism and vagueness of the New Age movement emerge as strengths rather than weaknesses. Which begs the question: if the early modern era witnessed a ‘decline of magic’ and a rise in institutionalised religious affiliation, are we now witnessing the opposite?

A solemn Englishman wearing a faux silver circlet, a green cape and a white knight’s doublet beats out a martial rhythm on bongo drums. He stands in a circle alongside a dreadlocked youth with a guitar and an older woman leaning on a wooden staff. At the center of the circle, a regal, snowy-haired environmental activist and former biker named Arthur Uther Pendragon anoints a kneeling man wearing face paint. The members of the circle welcome the newest druid of 2014.

It’s the summer solstice at Stonehenge, one of the epicentres of the Neo-Druid movement. The robed crowds that gravitate to Stonehenge on important dates in the lunar calendar see themselves as upholding ancient, pre-Christian rites. Despite a falling out with the leaders of the Druid Council, Arthur Pendragon remains one of the movement’s most charismatic leaders. (Not long ago, he anointed Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols as a bard of his breakaway order, the Loyal Arthurian Warband.)

In Pendragon’s earlier life, he was a working-class lad called John Timothy Rothwell from Yorkshire. After stints in the British Army and as the leader of an outlaw biker gang known as the Gravediggers, he experienced a spiritual awakening in the early 1980s and changed his name by deed poll in 1986. Pendragon began to regard himself as the reincarnation of King Arthur, even going so far as to buy the sword used as a prop in the film Excalibur (1981). A self-declared ‘English eccentric’, he and his former colleagues in the Druid Council proudly lay claim to a tradition of pagan practice that stretches back five millennia.

Considering his rakish, outlaw-biker-turned-legendary-king persona, Pendragon was remarkably easy to track down, and he proved to be both personable and generous with his time – not for nothing is he planning another run for the UK Parliament. Although members of the press frequently associate Pendragon and his druid followers with the New Age movement, he doesn’t see anything ‘new’ about it. ‘I personally do not see myself as New Age or Neo-Pagan, nor do I see myself as a part of the druid revivalist movement,’ Pendragon told me. ‘I feel that I am a druid practising the same belief structure and philosophy as was practiced by the ancients.’

As an historian, my impulse is to poke holes in claims to ‘authentic’, unbroken traditions. As the English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper pointed out in his essay ‘The Invention of Tradition’ (1983), even the tartan clan kilts of Scotland are in fact a product of a 19th-century reimagining of pre‑modern Highland Scots dress, owing far more to Romantic-era nostalgists such as Sir Walter Scott than to the rugged Highlanders of centuries past. By seeking to restore traditional customs that industrialisation had cast into shadow, nationalist writers and thinkers in the 19th and 20th centuries actually helped invent new ones.

the value of these claims to unbroken tradition lies not in their factual accuracy, but in their ability to instill a sense of empathy with the deep past

It’s tempting to apply the same argument to the Neo-Druids – that their enactment of ancient ceremonies based on spotty historical evidence is an invention of traditions, a 21st-century parody of Bronze Age beliefs about which even academic specialists can claim only the most tentative knowledge.

Yet perhaps those who would dismiss such re-enactments for their scholarly inaccuracy are missing the point. Folklorists and anthropologists have long sought to reconstruct pre‑modern magical practices – Gaelic charms, prayers to mother goddesses, bacchanalian rites – that resonate on an emotional and spiritual level, even if many of their details remain contested. Perhaps the value of these claims to unbroken tradition lies not in their factual accuracy, but in their ability to instill a sense of empathy with the deep past.

In Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret History (1992), a group of Classics students in rural Vermont becomes obsessed with recreating the ecstatic Dionysian frenzies of the Ancient Greek Bacchae, reliving pagan rites that had lain dormant for 2,000 years. Their leader Henry initially approaches the task as an anthropological challenge, a matter of systematically reconstructing ritual and gesture. But he soon realises that ‘it had to be approached on its own terms, not in a voyeuristic light or even a scholarly one’. In the end, Henry recalls: ‘I was struck by something rather obvious – namely, that any religious ritual is arbitrary unless one is able to see past it to a deeper meaning.’

In the 1970s and ’80s, the Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas argued for the existence of a matriarchal ‘Old European’ culture in the Neolithic (approximately 7,000 to 3,000 BCE). These were the forgotten peoples who had been conquered and subsumed by the Indo-European tribes that would become the Celts, the Germans, the Greeks and Romans, and the Persians. The Indo-Europeans tended to place male deities at the summit of their pantheon, often lightning-wielding sky gods such as Thor or Zeus. Yet Gimbutas conjectured that the Old Europeans were of the culture of the Mother Goddess, the upholders of a tradition that stretches back to the very earliest known sculptures made by human beings: the so-called Venus figurines of the Paleolithic period, some 25,000 years ago.

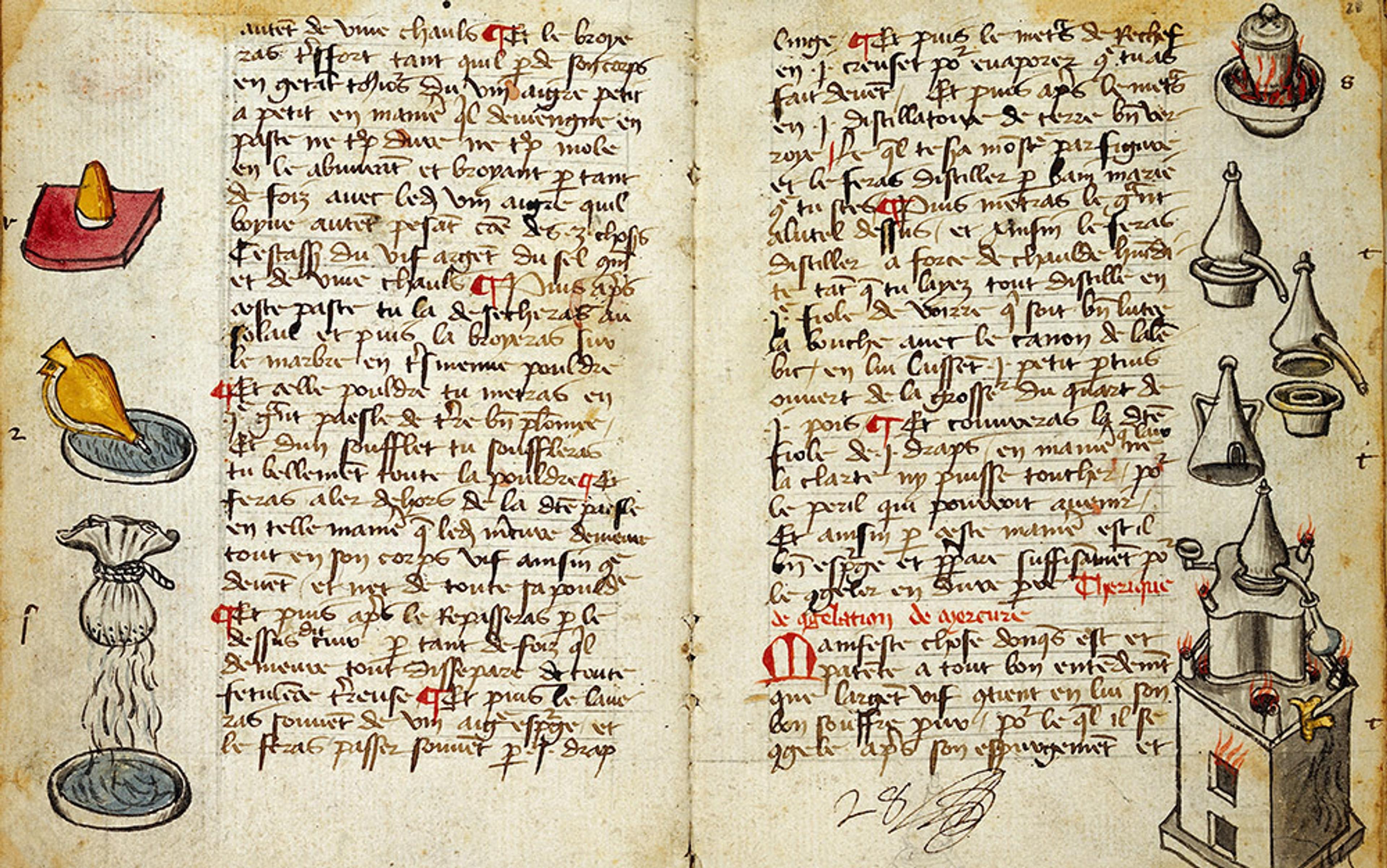

Building on the work of Gimbutas, some have argued that traces of this age-old religious tradition have survived to the present. Among academic historians, the fiercest debates over the survival of prehistoric matriarchal traditions in Europe have been waged over the question of the early modern witchcraft trials. Despite attempts to link the historical witch craze of the 16th and 17th centuries to the survival of ancient pre-Christian pagan practices, most historians of witchcraft and magic remain unconvinced. Yet in The Night Battles (1966), his celebrated ‘microhistory’ of a secret society of witch-fighters in 17th‑century northern Italy, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg, now of the University of California, Los Angeles, advances a similar, though more specific, claim. The witch-fighters, or ‘good walkers’ (i benandanti), Ginzburg speculates, were a vestigial remnant of a pre-Christian fertility cult that retained some of the ancient shamanistic traditions of Bronze Age Eurasia.

there is a ‘direct link’ between the occult movements of the late Enlightenment and the New Age movements of today

Such debates, though fascinating, are unlikely to be satisfactorily resolved. Yet even if we keep our minds open to the possibility that some fragments of ancient pagan practice can be recreated or survive through the millennia, in other respects the New Age movement is actually a product of the Enlightenment.

As the historian Paul Kléber Monod has pointed out in his book Solomon’s Secret Arts (2013), the Enlightenment was obsessed with the occult. From Isaac Newton (whom the British economist John Maynard Keynes called ‘not the first of the age of reason’ but ‘the last of the magicians’) to the secret societies of the Rosicrucians, the Freemasons and the Bavarian Illuminati, we find a culture simultaneously obsessed with attaining a perfect mastery over nature and the universal patterns pervading all spiritual traditions. Monod told me that he believes there is a ‘direct link’ between these occult movements of the late Enlightenment and the New Age movements of the present day.

But tracing that link takes us into shadowy territory: the vast metropolis of Victorian London, a hub of empires that pulled a variety of spiritual seekers into its fog-shrouded orbit. The figures involved in the creation of a more formalised New Age movement – people such as Aleister Crowley, Madame Blavatsky and George Gurdjieff – rarely saw eye to eye. But one thing they had in common was a mystical conviction that the world on the cusp of the 20th century was about to undergo an epochal change. They were right.

‘I have always considered myself a voice of what I believe to be a greater renaissance – the revolt of the soul against the intellect – now beginning in the world,’ wrote a 27-year-old W B Yeats in 1892. The Irish poet was an early follower of Madame Blavatsky, a Russian-German spiritual medium with a mesmerising gaze that was Rasputin-like in its intensity. Blavatsky is in some ways the ur-figure of the New Age movement, a modern-day prophet whose blending of ancient wisdom traditions with technologies of mass communication set a pattern that would play out again and again in the decades to come.

The members of the Theosophical Society that Blavatsky co-founded in New York in 1875 regarded their work as another manifestation of the march of scientific and technological progress, but they also believed they were tapping into supernatural realms of experience. ‘There is a hidden side to life,’ wrote Annie Besant and C W Leadbeater, both members of the Society, in their book Thought-Forms (1901). ‘Each act and word and thought has its consequence in the unseen world which is always so near to us, and that usually these unseen results are of infinitely greater importance than those which are visible to all upon the physical plane.’ Although they were writing here of invisible auras produced by music or emotional states, the authors could just as easily have meant Sigmund Freud’s notion of the subconscious, or a young PhD student named Albert Einstein’s work investigating the invisible medium of the ‘luminiferous aether’.

Science and technology went hand in hand with the dawning of the New Age. It’s no coincidence that beliefs about alternate worlds and invisible forces coalesced at the same time that telegraph cables and radio waves began to encircle the globe. Late Victorian London was the centre of this global technological network, but it was also the home to an emerging group of bohemians who tapped into these new technologies even as they reacted against them.

The 1920s and ’30s witnessed an efflorescence of new spiritual movements that embraced technologies of mass communication. Some represented outright breaks with organised religion, like the Kentucky-born mystic Edgar Cayce’s prophecies of Atlantis and extraterrestrials. (Cayce proved to be adept at attracting media attention from newspapers and radio broadcasters, and nurtured an early celebrity clientele that included everyone from President Woodrow Wilson and the composer George Gershwin to the inventor Thomas Edison.) Others, like the French philosopher and Jesuit priest Teilhard de Chardin blended the Judeo-Christian tradition with an eclectic mélange of concepts taken from Eastern religions, folk beliefs, physic and philosophy. The result was ideas such as Chardin’s notion of an ‘Omega Point’ when all human consciousness would merge and become one. The universalising science of the Enlightenment had mutated to become a universalising spiritual movement.

During the 1960s and ’70s, the diverse points of origin for New Age thought coalesced into identifiable subcultures. Groups such as the Wicca/Goddess movement, the Rainbow Family, the Human Potential Movement and proponents of Transcendental Meditation expanded the social framework for New Age beliefs away from purely spiritual organisations and toward a more lifestyle-based orientation.

Parsons would chant Aleister Crowley’s hymn to the Greek God Pan before every rocket test

In his PhD dissertation ‘The Rocket and the Tarot’ (2010), the historian Matthew Tribbe, now at the University of Connecticut, identified the years following the final Apollo moon landing (1972) as the moment when a broad-based societal belief in technological progress lost ground to interest in the occult, the esoteric, and the irrational. ‘Millions of Americans defected from their secularised mainline congregations to form new, more spiritual-focused parishes, or even bolted their denominations all together in favour of the evangelical and fundamentalist or New Age faiths that mushroomed in the early 1970s,’ writes Tribbe. ‘This religious revival was only one part of a much larger cultural upheaval that saw a widespread questioning and often rejection of the more general rationalism of the postwar era.’

Yet we might also regard the New Age movements of the 1970s as arising from – rather than defeating – this Apollo-era conviction in the power of technology. In the 1930s, while he was immersing himself in the theoretical physics that underpinned the first atomic bomb, for instance, the young physicist J Robert Oppenheimer was also learning Sanskrit and compulsively reading (and comparing himself to) ancient Vedic scripture. Similarly, even as the rocket scientist Jack Parsons was co-founding the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Cal Tech, he was becoming immersed in alchemical lore and occultism, performing ‘sex magic’ in his Pasadena mansion with a rotating cast of bohemian Los Angeles characters. Parsons would chant Aleister Crowley’s hymn to the Greek God Pan before every rocket test, and he claimed his discovery of solid rocket fuel in 1942 (which laid the groundwork for the Apollo space program) derived from his mystical ‘intuition’.

Before Parsons accidentally blew himself up in his home alchemical lab in 1952, he had welcomed into his Pasadena home a Second World War veteran who’d been expelled from the Navy for psychological instability: L Ron Hubbard. The two men shared a love for science fiction and black magic. But in 1946 Hubbard ran off with Parsons’ mistress Sara – and his yacht. Parsons invoked a Babylonian god and (he believed) stirred up the typhoon that caused their boat to capsize, but Hubbard and Sara survived. The next year, Hubbard would begin writing Dianetics, which mingled Crowley-esque occultism with Atomic Age scientific jargon. Indeed, by this time, Hubbard was claiming to be a nuclear physicist. Scientology would emerge a few years later.

Is the New Age a mere cultural fad, a set of aesthetic signifiers and intellectual fashions that will fade as a societal force? Certainly, one breed of New Age aficionado seems destined to age out of 21st-century society. These are the types that the English novelist Edward St Aubyn assembled for his satire On the Edge (1998), which narrates the adventures of 12 spiritual seekers on the road to the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, with a blend of bemused horror and empathy. The hapless protagonists – Crystal, Krater, Stash, Jean-Paul, and the rest – are undoubtedly modelled in part on St Aubyn’s mother Lorna, an Anglo-American heiress who retreated from family tragedy by converting her French château into a New Age institute. But if the crystals-and-auras guise of the New Age has begun to take on a distinctly vintage character, this does not tell the whole story.

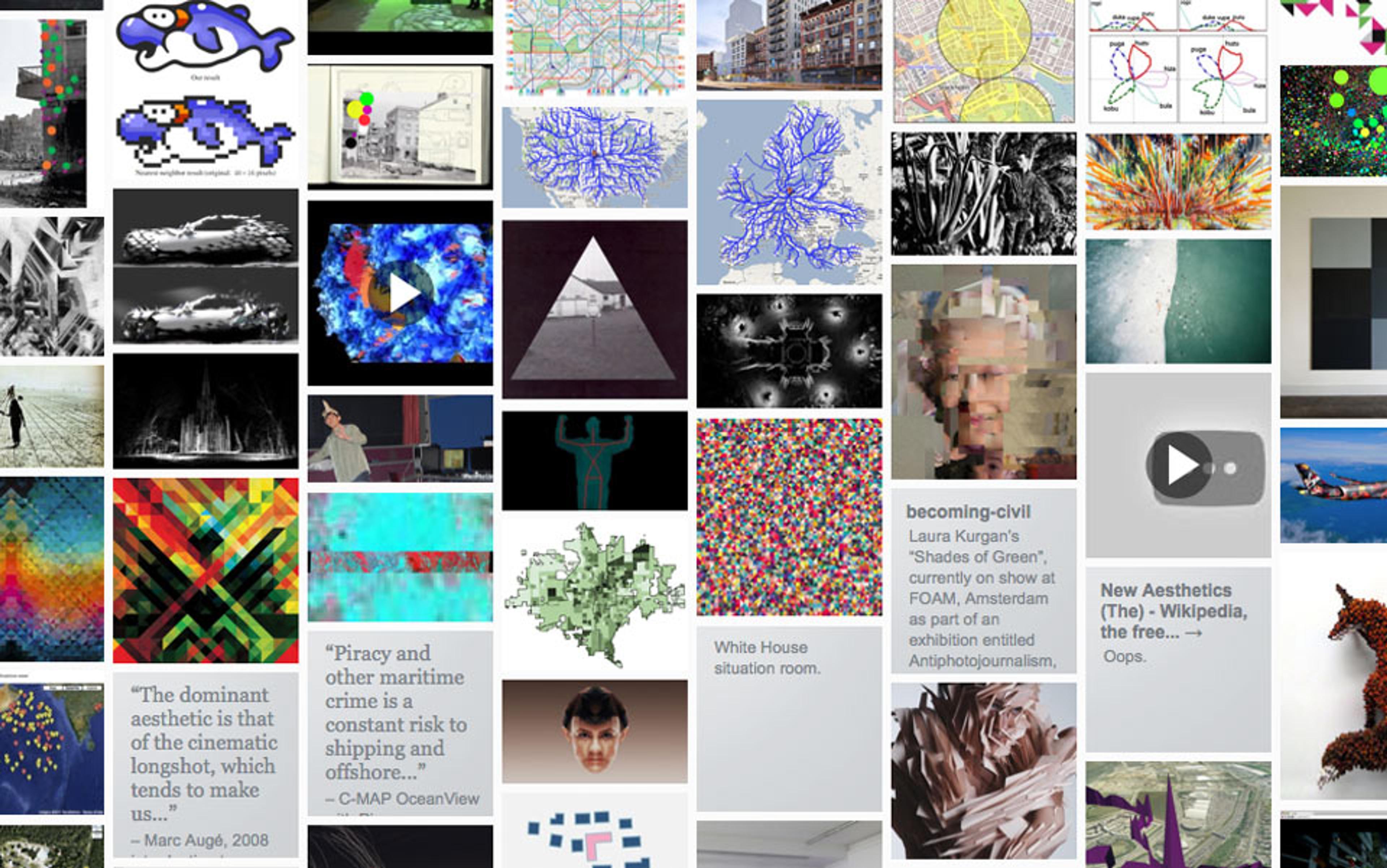

Take Silicon Valley in California, which began with the skinny-tie IBM engineer aesthetics of the 1950s but began to acquire its contemporary contours thanks to the LSD-inflected eclecticism of the 1970s. From Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog to the holistic take on computing promulgated by an India-roaming psychedelic enthusiast named Steve Jobs, elements of the New Age counterculture have been encoded in the DNA of Silicon Valley almost from the beginning.

the line between those who seek transcendence in technology and a ‘re-enchantment of the world’ will become increasingly blurred

In Who Owns the Future (2013), the US computer scientist Jaron Lanier describes a shift in emphasis from what we might call the ‘traditional’ New Age milieu of the 1980s San Francisco Bay Area tech scene – macrobiotic cooking, self-actualisation, spiritual gurus, et al – and the trans-humanist faction that prevails in the 2010s. Trans-humanists or Singularitarians represent the revolutionary vanguard of Silicon Valley’s technological utopianism, but their intellectual lineage is an eclectic one. As the open source advocate Tim O’Reilly put it at his Long Now Foundation talk ‘Birth of the Global Mind’ (2012), Teilhard de Chardin’s post-Second World War vision of a mystical expansion of human life into the furthest bounds of the universe was ‘the Singularity of its day’. Yet for the Singularitarians, Teilhard’s vision will become realised not only by a blossoming of human consciousness, but by the melding of that consciousness with a new breed of what the US computer scientist Ray Kurzweil calls ‘spiritual machines’. The interconnected nature of social media and the internet of things, which draws individual human minds into communion with the built environment that surrounds them, thus takes on an almost spiritual dimension.

To be sure, techno-utopians embrace a far more straightforward view of technological progress than their New Age counterparts, and one doubts that a Kurzweil would find much common cause with the Neo-Druids. But in the decades to come, I expect the line between those who seek transcendence in technology and a ‘re-enchantment of the world’ to become increasingly blurred.

Already in 1941, when T S Eliot versified in Four Quartets about Londoners who try ‘To communicate with Mars, converse with spirits/ To report the behaviour of the sea monster/ Describe the horoscope, haruspicate or scry… fiddle with pentagrams/ Or barbituric acids’, the line was blurring. The esoteric fringes of modern science were becoming entanged with ancient traditions such as astrology and the Tarot. For Eliot, a former dabbler in Blavatsky’s Theosophism who by this time associated true religious profundity with the Catholic tradition, these magical practices were all manifestations of a superficial spirituality, the ‘usual/ Pastimes and drugs, and features of the press’.

Eliot was on to something in that final phrase. Technologies of mass communication allowed the various beliefs that coalesced under the New Age banner to establish themselves as popular alternatives to traditional religion. With such metrics of allegiance to organised religion as churchgoing and tithing in decline, New Age eclecticism (amplified by radio, newspapers and eventually the internet) emerged as a kind of modern magic. Weber might have been right that the rise of modernity required the death of the enchanted world. But in that sleep of death, what dreams may come?