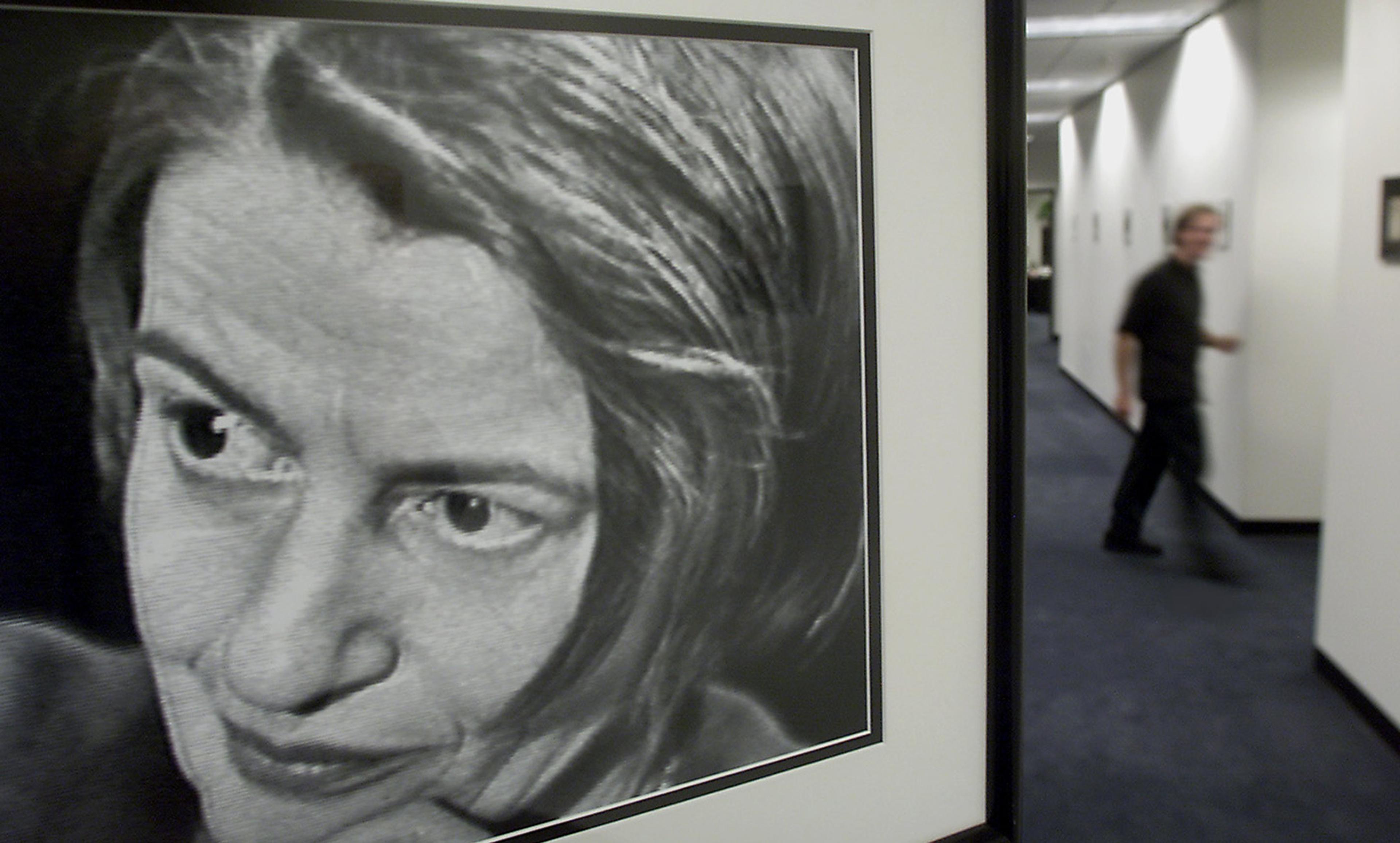

Charlotte Perkins Gilman addressing members of the Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1916. Photo by Getty

Charlotte Perkins Gilman is best known today for ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ (1892), a widely anthologised short story that mixes Gothic conventions with feminist insights, and a chilling dissection of patriarchy that seems as if it might have been co-authored by Edgar Allan Poe and Gloria Steinem. Fewer people know that Gilman began her career as a speaker and writer on behalf of Nationalism, a short-lived political movement inspired by Edward Bellamy’s best-selling utopian novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (1888). She ended it as a writer of her own utopian fictions, including Herland (1915), a playful novel about an ideal all-female society.

What does Gilman’s utopian feminism have to say to us now, when the dystopian pessimism of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) is resurgent?

As a young woman, Gilman was drawn to Bellamy’s utopian socialism because of his stance on women’s economic independence; in the society depicted in Looking Backward, every woman and man earns an ‘equal credit’. Bellamy was certain that, from this economic parity, gender equality would follow. Gilman took a different approach. She believed that the realisation of utopia depended on women’s ‘mother instinct’, and advocated what she called the ‘larger motherhood’. As she wrote in her Bellamyite poem ‘Mother to Child’ (1911):

For the sake of my child I must hasten to save

All the children on earth from the jail and the grave.

Her life’s work centred on the concept of what she called the ‘World’s Mother’ – the selfless, nurturing woman-spirit who loves, protects and teaches the entire human race.

During the first decade of the 20th century, following the collapse of Bellamy’s Nationalist movement, Gilman turned to utopian fiction, producing three novels, a novella, and a flock of short stories. All were variations on the same utopian blueprint: the ideal society could be achieved peacefully in a remarkably short time if only women were freed from conventional housework and childrearing (she envisioned a combination of communal living and professional childcare) in order to spread the self-sacrificing ethics of the larger motherhood.

In 1915, she broke this fictional mould with Herland, a utopian fantasy that combines the plot of Alfed, Lord Tennyson’s The Princess (1847) – the discovery of an all-female society – with the conventions of the masculine adventure tale. Three bold young men on a scientific expedition to a remote part of the globe hear tales of a land inhabited only by women, located in an inaccessible mountain range. The men obtain a biplane and pilot it into the mountains, where after landing they soon spy three beautiful young women and give chase. The athletic young women, sensibly attired in utopian bloomers, easily outrun the men, who are captured by a phalanx of unarmed but well-disciplined women who chloroform them and place them under house arrest in a guarded fortress.

At this point, the novel transitions into utopian exposition, with long disquisitions on Herland’s society. Gilman was remarkably indifferent to the typical concerns of utopian fiction: work, politics, government. Instead, she used her fantastical premise to focus on her own interests, such as animal rights. Herlanders have eliminated all domesticated animals because of the cruelty inherent in slaughtering them for food. They are appalled at the idea of separating cows from their calves. Any interference with the natural processes of mothering is abhorrent to them.

Mothering is at the centre of Herland society. The word ‘mother’ or its variants appears more than 150 times in the novel. The women of Herland reproduce parthenogenetically, bearing only daughters, who are raised communally: each child is regarded as the child of all. ‘We each have a million children to love and serve,’ one of the women explains. Gilman evidently felt no need to explain Herland’s economy because it seemed to her so obvious: these ‘natural cooperators’, whose ‘whole mental outlook’ is collective, have no use for the individualism and competitiveness inherent in capitalism. Instead, a motherly state meets every citizen’s basic needs.

Herland depends on Gilman’s interpretation of women’s ‘maternal instinct’, an idea she clung to despite her own disastrous experience as a mother. Following the birth of her only child, a daughter, when Gilman was 24, she was plunged into a horrendous depression, an episode that she drew on for ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’. When her daughter was three, Gilman separated from her husband; six years later, she divorced him and gave up custody of their child. Herland enabled her to reconcile the contradictions between her utopian celebration of the maternal spirit and her difficult personal experience. Although every woman in Herland is capable of parthenogenetic reproduction, only an elite is entrusted with rearing children, in a collectivised and professionalised fashion. Gilman’s interest in the topic blended her conviction that women, like men, owed it to the world to work outside the home with her self-exculpating belief that the raising of children is so vital to the future race that it must be entrusted to professionals. Gilman derided the smallness, the possessiveness of the average woman’s conception of motherhood: my children, my family, my home. Herlanders see every child as theirs, the entire population as one family, the nation as home.

Herland dropped out of view soon after its publication. Gilman had serialised the novel in The Forerunner, her self-published magazine, which folded soon after, and it never came out in book form. The novel was resurrected in the late 1970s by the American scholar Ann J Lane, who edited a paperback edition. Initially, the novel was hailed as a rediscovered feminist classic. Later scholars were more critical. They singled out its gender essentialism, but also the eugenic regime that underlay Gilman’s utopianism: her obsession with improving the strategically undefined ‘race’. Drawing on Gilman’s other writings, they convincingly argued that white racism is central to her utopian project.

Four decades after its rediscovery, Herland no longer seems the purely playful, light-hearted speculative fiction it once did. Nor does its central theme of collective child-rearing seem that different from the gendered regimes animating The Handmaid’s Tale – which, with an unabashed sexist and racist in the White House, serves as a powerful cautionary tale for progressives. Dystopian fiction, however, lacks the visionary inspiration – what the German philosopher Ernst Bloch in the 1950s called ‘the principle of hope’ – that utopianism provides.

Despite Herland’s time-bound shortcomings, we need its vision of a society without poverty and war, where every child is precious and inequalities of income, housing, education and justice are nonexistent. For all its faults, Herland remains an eloquent expression of the nonviolent democratic socialist imagination. As fully as any work in the utopian tradition, Herland reminds us of the truth of Oscar Wilde’s aphorism: ‘A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.’

The Last Utopians: Four Late 19th-Century Visionaries and Their Legacy (2018) by Michael Robertson is published via Princeton University Press