An owl from a bestiary (c1226-50), England. MS Bodley 764, Folio 73v. Courtesy Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

The owl watches you from the raised seat on the medieval misericord in Norwich Cathedral in the east of England. Surrounding the owl are birds with feathers like the scales of a pangolin. The birds are focused on the owl. The owl pays them no mind.

The motif of this scene would have been familiar to the woodcarver who made it and to the abbey monks who leaned against it during the long hours of Mass. But the associations the people of the Middle Ages made when they saw the scene on the misericord seat were different from how we would interpret it today.

A medieval person would have looked upon the owl and the birds and seen a Christian parable. Drawing from the Roman tradition of associating owls with death and sickness, the medieval person would have seen a filthy animal further defiled by its nocturnal habits. He would also have seen a Jew.

Similar to how the owl avoids the light of day, the parable went, so the sinner avoids the light of Christ. The birds surrounding the owl are neither listening to it nor admiring it, as perhaps we would think today when viewing an image of Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and war. No, these birds are attacking the owl and, through their act of violence, the birds represent the virtuous who react to the sinner in their midst.

Befitting the agenda of the medieval Church, the owl was the perfect animal to represent the Jews. According to the Church, no other group turned away from Christ more decisively than them. Anyone who was not with Christ was with the Devil, and consequently evil. Evil dwells in darkness and is unclean, just like the owl. The owl surrounded by the attacking birds is the Jew surrounded by Christians vanquishing evil. In short, what we see when we look at the scene on the seat of the misericord in Norwich Cathedral is an example of medieval antisemitism.

The scene of the owls and the birds, and the knowledge of its symbolic meaning, come from a medieval book genre known as a bestiary. Bestiaries were popular during the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly in England where they became an important part of religious didactic literature. The history of the bestiary as book genre is long. Even so, its exact origins are hazy. What we do know is that the story of how the bestiary came to be begins in early Christian Egypt.

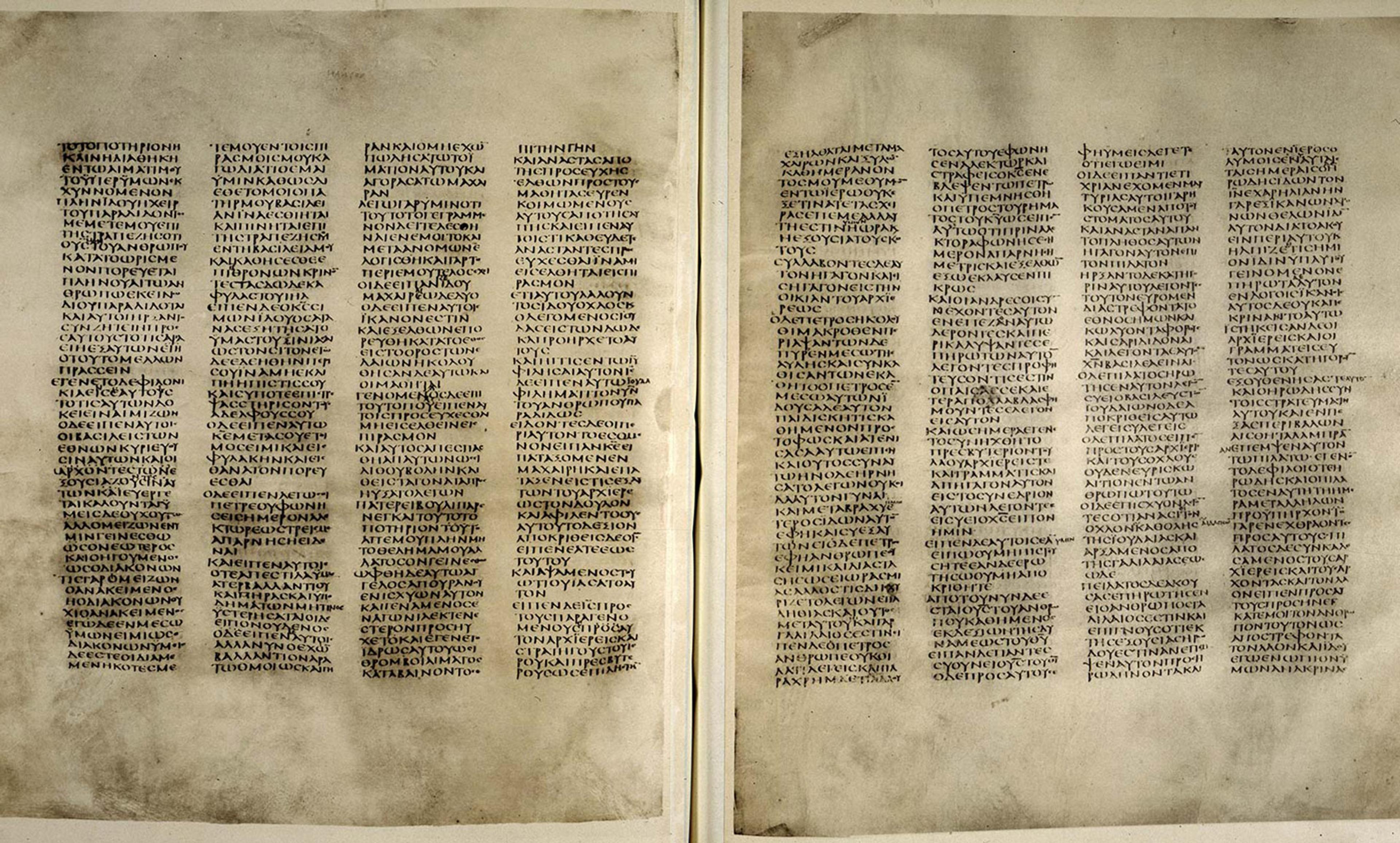

Some 1,900 years ago, an anonymous author in Alexandria created a book known as the Physiologus. This is the earliest known book that organises animal stories into short narrative chapters. The stories of the Physiologus drew from the animal lore of the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa, and placed them within a Christian framework. Originally written in Greek, the Physiologus was translated into several different languages, and spread across the Mediterranean and Europe.

Fast-forward to Andalusia in Spain, 500 years later, when Archbishop Isidore of Seville was busy working on a momentous task – an encyclopaedia meant to gather and explain all the knowledge of the world. Unfinished at the time of his death in 636, Isidore’s encyclopaedia (called the Etymologiae) would go on to become one of the most influential books of learning in the Middle Ages.

At some point in time, the Physiologus and the Etymologiae crossed paths, and the bestiary was born. A bestiary consists of images of real and fantastical animals accompanied by an explanation of the characteristics of each animal. Its African origins are clear. As well as European animals such as farm horses, dogs, red foxes and bunny rabbits, there are also elephants, crocodiles, giraffes and lions.

The main purpose of the bestiary was not to teach about the animal kingdom, but to teach people how to lead the life of a virtuous Christian. To make this point as clear as possible, the bestiaries divide all animals into groups of good and evil. Which animal belonged to which group was explained in the text, and through the placement of the animal’s illustration on the page. Good animals were at the top of the page facing right. Evil animals were at the bottom of the page, facing left. Good animals, such as the stag, the phoenix and the panther, represented Christ and his followers. Evil animals represented the Devil. Here we find the dragon, the hyena, the weasel and, of course, the owl.

The antisemitism found in the bestiaries is only one of the many ways that the anti-Jewish agenda of the Church expressed itself in the Middle Ages. This agenda was powerfully codified by the influential Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, when the conditions for Jewish life in Latin Christendom became officially regulated.

The turning point in the popularity of the bestiaries is the Edict of Expulsion, issued in 1290 by King Edward I of England. This edict forced all Jews to leave the country without exception. England would not have a permanent Jewish population again until the mid-17th century. Soon after the Edict had gone into effect and all the Jews had left, bestiaries all but ceased to be produced.

The key to the bestiary’s influence on medieval English society was its images. With support from the stories told in the weekly sermons held in parish churches, these images made the allegories accessible to those who couldn’t read or were unable to afford their own bestiary. So influential were they that bestiary images showed up in places unrelated to them long after they had gone out of style and the Jews of England were gone. The scene of the owl and the birds in Norwich Cathedral is one of many examples of this antisemitism without Jews; the misericord and its seat were placed in the cathedral in the 15th century, almost 200 years after the Edict of Expulsion.

Since the Middle Ages, the owl has come to symbolise wisdom. Yet the legacy of the bestiary lives on, and comparing Jews to undesirable animals remains a common antisemitic trope.