Mine! Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/Getty.

In 1859, around 450 passengers on the Royal Charter, returning from the Australian goldmines to Liverpool, drowned when the steam clipper was shipwrecked off the north coast of Wales. What makes this tragic loss of life remarkable among countless other maritime disasters was that many of those on board were weighed down by the gold in their money belts that they just wouldn’t abandon so close to home. Humans have a particularly strong and, at times, irrational obsession with possessions. Every year, car owners are killed or seriously injured in their attempts to stop the theft of their vehicles – a choice that few would make in the cold light of day. It’s as if there is a demon in our minds that compels us to fret over the stuff we own, and make risky lifestyle choices in the pursuit of material wealth. I think we are possessed.

Of course, materialism and the acquisition of wealth is a powerful incentive. Most would agree with the line often attributed to the actress Mae West: ‘I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor – believe me, rich is better.’ But there comes a point when we have achieved a comfortable standard of living and yet we continue to strive for more stuff – why?

It is unremarkable that we like to show off our wealth in the form of possessions. In 1899, the economist Thorstein Veblen observed that silver spoons were markers of elite social position. He coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’ to describe the willingness of people to buy more expensive goods over cheaper, yet functionally equivalent, goods in order to signal status. One reason is rooted in evolutionary biology.

Most animals compete to reproduce. However, fighting off competitors brings with it the risk of injury or death. An alternative strategy is to advertise how good we are so that the other sex chooses to mate with us rather than with our rivals. Many animals evolved attributes that signal their suitability as potential mates, including appendages such as colourful plumage and elaborate horns, or ostentatious behaviours such as the intricate, delicate courtship rituals that have become markers of ‘signalling theory’. Due to the unequal division of labour when it comes to reproduction, this theory explains why it is usually the males who are more colourful in their looks and behaviour than the females. These attributes come at a cost but must be worth it because natural selection would have disposed of such adaptations unless there was some benefit.

Those benefits include genetic robustness. Costly signalling theory explains why such apparently wasteful attributes are reliable markers of other desirable qualities. The poster child for costly signalling is the male peacock, who has an elaborately coloured fantail that evolved to signal to peahens that they possess the finest genes. The tail is such a ludicrous appendage that in 1860 Charles Darwin wrote: ‘The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail makes me sick.’ The reason for his nausea was that this tail is not optimised for survival. It weighs too much, requires a lot of energy to grow and maintain, and, like a large Victorian crinoline dress, is cumbersome and not streamlined for efficient movement. However, even if heavy displays of plumage might pose a disadvantage under some circumstances, they also signal genetic prowess because the genes responsible for beautiful tails are also those associated with better immune systems.

Both male and female humans also evolved physical attributes that signal biological fitness but, with our capacity for technology, we can also display our advantages in the form of material possessions. The wealthiest among us are more likely to live longer, sire more offspring and be better prepared to weather the adversities that life can throw at us. We are attracted to wealth. Frustrated drivers are more likely to honk their car horn at an old banger than at an expensive sportscar, and people who wear the trappings of wealth in the form of branded luxury clothing are more likely to be treated more favourably by others, as well as to attract mates.

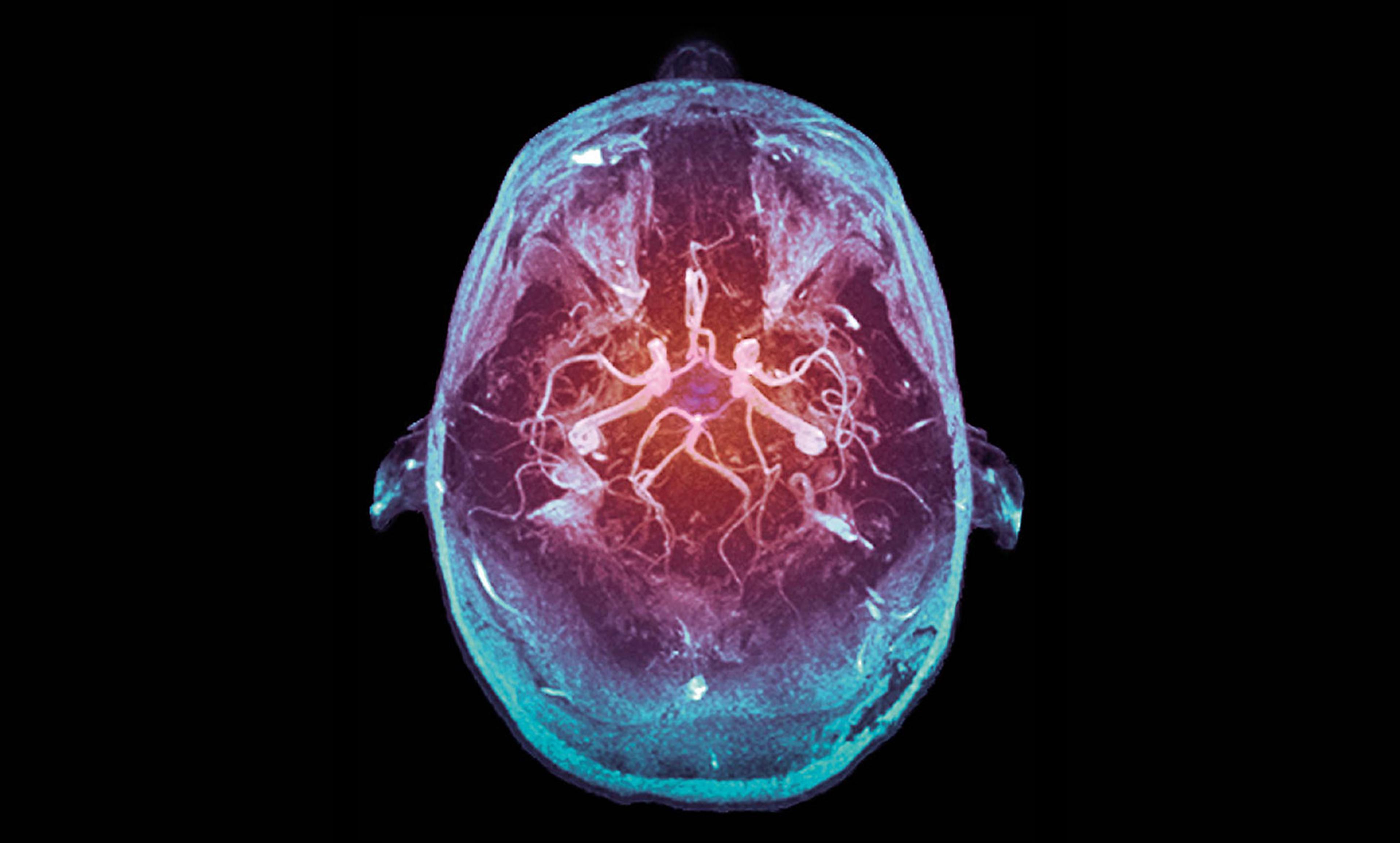

While having stuff signals reproductive potential, there is also a very powerful personal reason for wealth – a point made by Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, when he wrote in 1759: ‘The rich man glories in his riches, because he feels that they naturally draw upon him the attention of the world.’ Not only does material wealth make for a more comfortable life, but we derive satisfaction from the perceived admiration of others. Wealth feels good. Luxury purchases light up the pleasure centres in our brain. If you think you are drinking expensive wine, not only does it taste better but the brain’s valuation system associated with the experience of pleasure shows greater activation, compared with drinking exactly the same wine when you believe it to be cheap.

Most importantly, we are what we own. More than 100 years after Smith, William James wrote about how our self was not only our bodies and minds but everything that we could claim ownership over, including our material property. This would later be developed in the ‘extended self’ concept by the marketing guru Russell Belk who argued in 1988 that we use ownership and possessions from an early age as a means of forming identity and establishing status. Maybe this is why ‘Mine!’ is one of the common words used by toddlers, and more than 80 per cent of conflicts in nurseries and playgrounds are over the possession of toys.

With age (and lawyers), we develop more sophisticated ways of resolving property disputes, but the emotional connection to our property as an extension of our identity remains with us. For example, one of the most robust psychological phenomena in behavioural economics is the endowment effect, first reported in 1991 by Richard Thaler, Daniel Kahneman and Jack Knetsch. There are various versions of the effect, but probably the most compelling is the observation that we value identical goods (eg, coffee mugs) equally until one becomes owned, whereupon the owner thinks that his or her mug is worth more than a potential buyer is willing to pay. What is interesting is that this effect is more pronounced in cultures that promote greater independent self-construal compared with those that promote more interdependent notions of the self. Again, this fits with the extended-self concept where we are defined by what we own exclusively.

Normally, the endowment effect doesn’t appear in children until around six or seven years of age, but in 2016 my colleagues and I demonstrated that you can induce it in younger toddlers if you prime them to think about themselves in a simple picture-portrait manipulation. What is remarkable is that the endowment effect is weak in the Hadza tribe of Tanzania who are one of the last remaining hunter-gathers where ownership of possessions tends to be communal, and they operate with a policy of ‘demand-sharing’ – if you’ve got it and I need it, then give it to me.

Belk also recognised that the possessions that we see as most indicative of ourselves are the ones that we see as most magical. These are the sentimental objects that are irreplaceable, and often associated with some intangible property or essence that defines their authenticity. Originating in Plato’s notion of form, the essence is what confers identity. Essentialism is rampant in human psychology as we imbue the physical world with this metaphysical property. It explains why we value original works of art more than identical or indistinguishable copies. Why we would happily hold a biography of Adolf Hitler detailing his atrocities but feel repulsed to hold his personal cookbook with no mention of his crimes. Essentialism is the quality that makes your wedding ring irreplaceable. Not everyone acknowledges his or her essentialism, but it is at the root of some of the most acrimonious disputes over property, which is when they have become sacred, and part of our identity. In this way, possessions not only signal who we are to others, but remind us who we are to ourselves, and of our need for authenticity in an increasingly digital world.

This piece is based on the book ‘Possessed: Why We Want More Than We Need’ (2019) © Bruce Hood, published by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books