Not William Penn. Photo by Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images

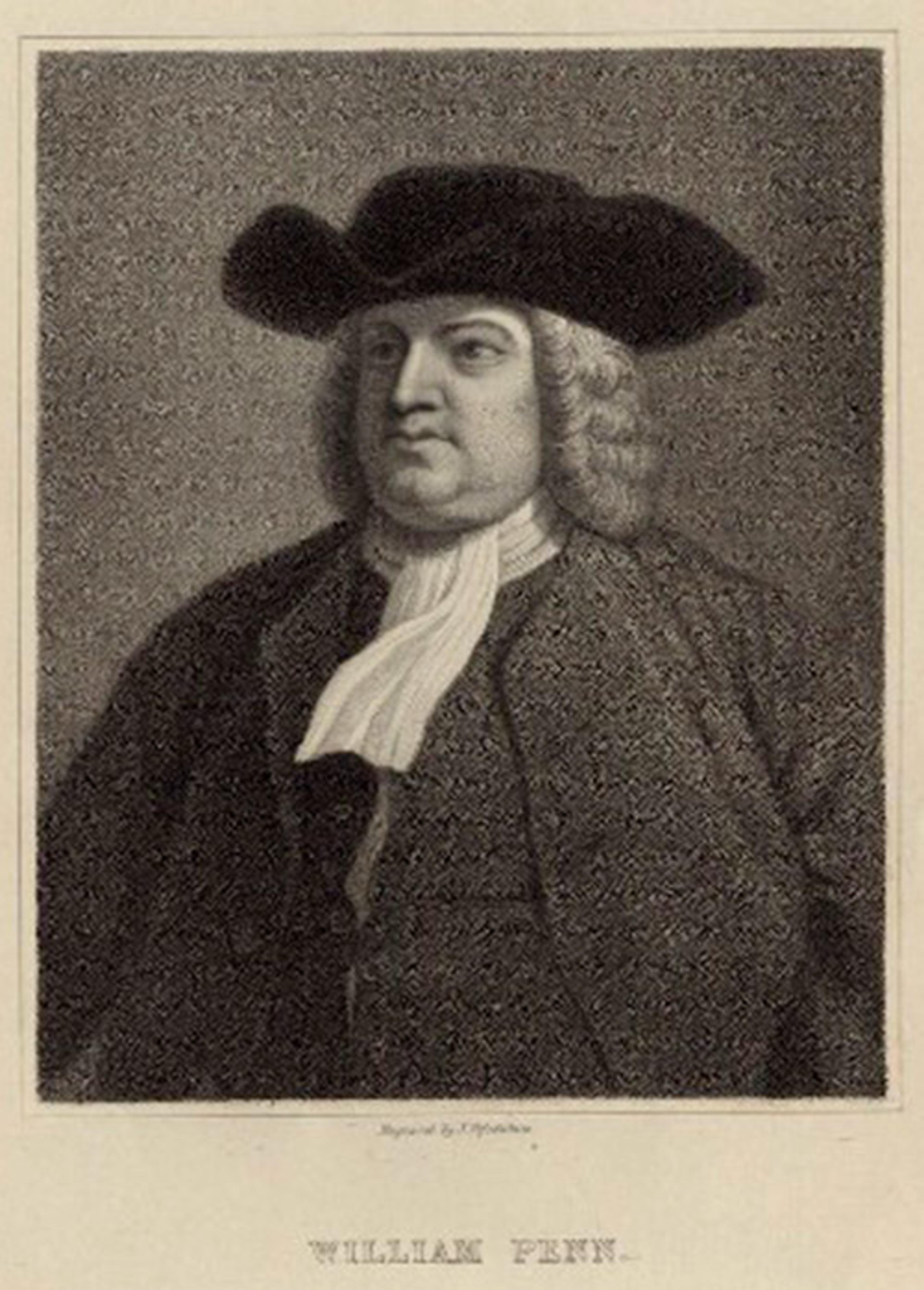

This year marks the 300th anniversary of the death of William Penn. For someone with such a prominent name, he remains a little-known and much-misunderstood figure. Iconic representations abound, of course, none more prominent than the 37-foot bronze statue atop Philadelphia City Hall. In that rendering, decked out in lace cuffs and holding his colonial charter, Penn looks every bit the far-seeing, visionary founder. Many assume that the familiar face on the Quaker Oats box, with its peaceful mien and slightly bemused smile beckoning the viewer to a healthy breakfast, is Penn. And then there is the portly older Penn, wearing a serious expression – a scowl, almost – and a vest that seems barely to button around his midsection.

There are others, of course, including the images of Penn meeting with the Lenni Lenape under the Treaty Elm at Shackamaxon, which both reflected and reinforced Pennsylvania’s powerful founding mythos differentiating Penn’s just treatment of natives from the violence countenanced by other colonial founders.

But how much do we really know about Penn? The meeting under the Treaty Elm probably never happened. And neither the City Hall statue nor the rotund elder – and certainly not the Quaker Oats label – give any sense of the drama of Penn’s life, the heady successes and crushing failures, his grand vision and his tendency to self-pity and grudge-holding.

William Penn. Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Penn was a man of paradoxical qualities. He espoused a radically egalitarian Quaker theology, insisting that something divine resided within each individual, yet he owned slaves on his American estate. He praised representative institutions such as parliament and the jury system, but spent years in hiding for his loyalty to an absolutist king. ‘I am like to be an adopted American,’ he wrote shortly after arriving in Pennsylvania in 1682, but spent only four of his remaining 36 years there. And he was chronically incapable of managing money, spending eight months in an English debtors’ prison in his 60s, even while his colony quickly became a commercial success.

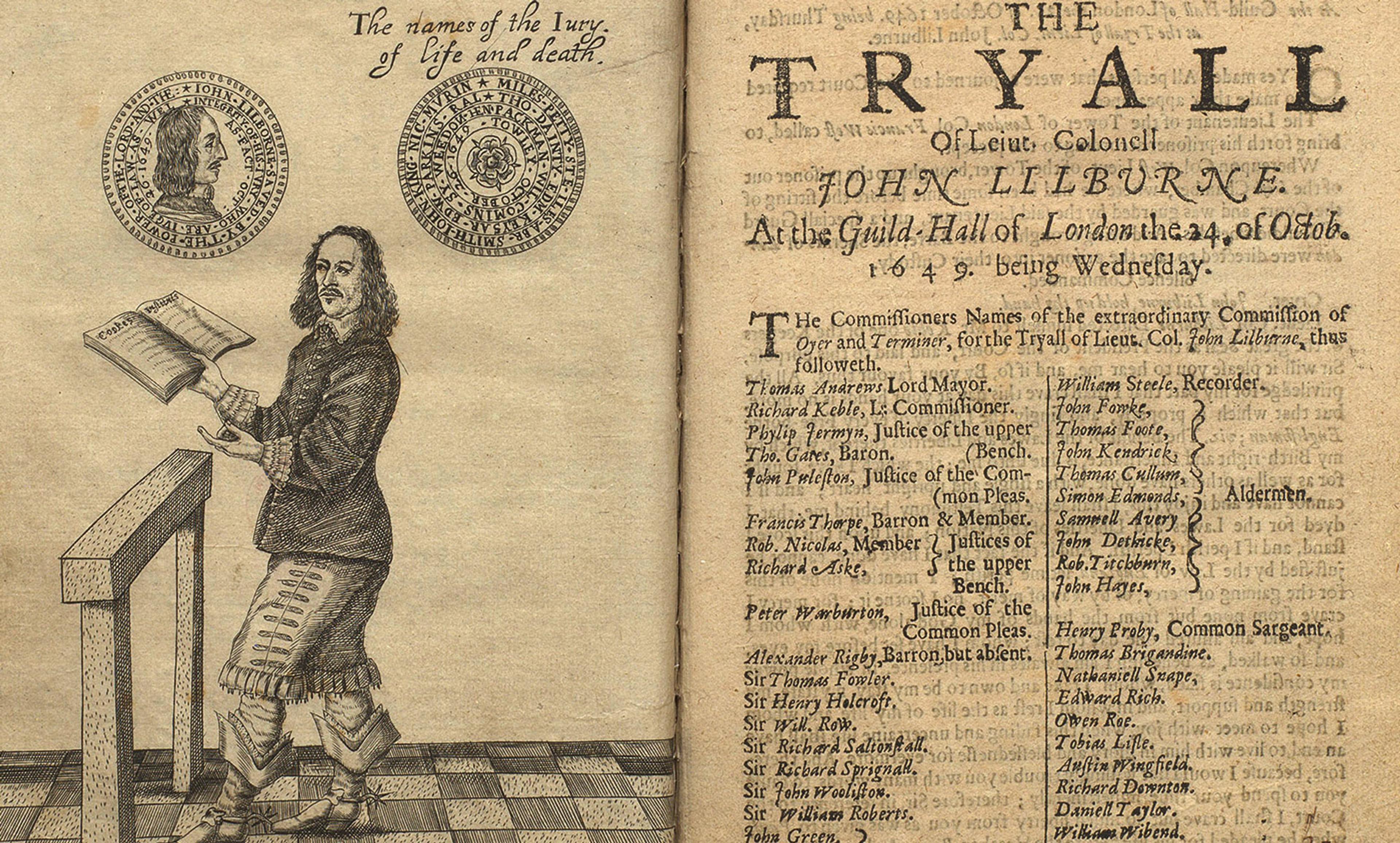

Born in 1644, Penn was groomed by his father, a naval hero who owned thousands of acres of expropriated Irish land, for a life of privilege and influence. That plan suffered its first setback when a teenage William was sent home from the University of Oxford – training ground for England’s elite – for religious nonconformity. But it really collapsed when Penn had a profound spiritual transformation in Ireland in 1667, joining the Quakers (aka the Society of Friends), one of the most radical and unpopular sects around. His faith cost Penn four imprisonments while still in his 20s, and his father kicked him out of the family home for his conversion.

But as one door closed, another opened, and Penn soon became one of the best-known religious dissenters in England. Over the course of the 1670s, he travelled throughout England and across Europe, spreading the Quaker message and advocating liberty of conscience in dozens of publications and appeals to political authorities. By the end of that decade, as a political crisis gripped England, and Quakers faced continuing persecution, Penn hit upon a new idea: an American colony that might offer a kind of ‘holy experiment’ – perhaps even grow into the ‘seed of a nation’ – where adherents of many religions might live in peace, mutually committed to each other’s welfare even while each worshipped as they saw fit. He parlayed a debt from the Crown into a massive American land grant, named it for his father (or, perhaps, himself), and sailed for America in 1682.

Penn’s was not the only settlement offering a measure of respite from the religious strife roiling Europe. But he was an especially prominent figure, charismatic and well connected, and thousands of settlers made their way to his settlement during the 1680s.

Penn remained in his colony from 1682 to 1684, enthusiastically overseeing the business of founding. Before long, however, he encountered the proverbial fly in the ointment, in the person of Charles Calvert (Lord Baltimore), his southern neighbour. Conflict over control of what were then known as the ‘Lower Counties’ – the present-day US state of Delaware – lay at the heart of the dispute. By mid-1684, both men had returned to London to argue their cases in person. Penn emerged victorious but, instead of returning to America, he opted (in what has been called ‘the greatest mistake of his life’) to stay in England, where he had an old friend in the new king, James II. Aided by Penn, James embarked on an ambitious effort to do away with persecutory legislation and enact liberty of conscience by bypassing parliament and ruling by royal decree. It was an extremely controversial campaign that came crashing down when William of Orange invaded England in 1688, and James was ejected from the throne. Penn likely saw nothing ‘glorious’ in this revolution.

Penn’s Treaty with the Indians by Edward Hicks, c1840-1844. Courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington

James was fortunate enough to flee to France; Penn was not so lucky. Imprisonments on suspicion of treason followed, along with years in hiding and temporary loss of control over Pennsylvania. The next five years were a low point, and only in 1699 did he make his long-delayed return to Pennsylvania. But it was hardly the same place, and he was not the same man: the founding magic had gone. It seemed almost a relief to all concerned when Penn, worried about potential parliamentary legislation to strip colonial governments from their proprietors, decided to return to England after just two years.

After his second, and final, departure from Pennsylvania, Penn’s life was a series of struggles to maintain control of his colony, remain relevant in English politics, and get his ever-problematic finances in order. He was not entirely successful on any of these fronts, spending much of 1708 in a debtor’s prison, ultimately deciding to sell the government of Pennsylvania back to the Crown in return for a cash payment. And even this promising financial windfall would prove elusive, as he suffered a debilitating stroke in 1712 and was incapacitated for the remaining years of his life. He died in 1718, and was buried in the grounds of the Jordans Meetinghouse, about 30 miles west of London.

But Penn’s death was hardly the end of his influence, and his disappointment at Pennsylvania’s affairs is surely not the final word. The settlement he brought into existence had thrived in spite (or because?) of the founder’s long absences, and it continued to flourish after his death. Philadelphia quickly emerged as an intellectual, economic and political powerhouse on American shores. Culturally vibrant and ethnically and religiously diverse, it would host Continental Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, and served as the new nation’s capital between 1790 and 1800.

The Grave of William Penn by Edward Hicks, c 1847-48. Courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington

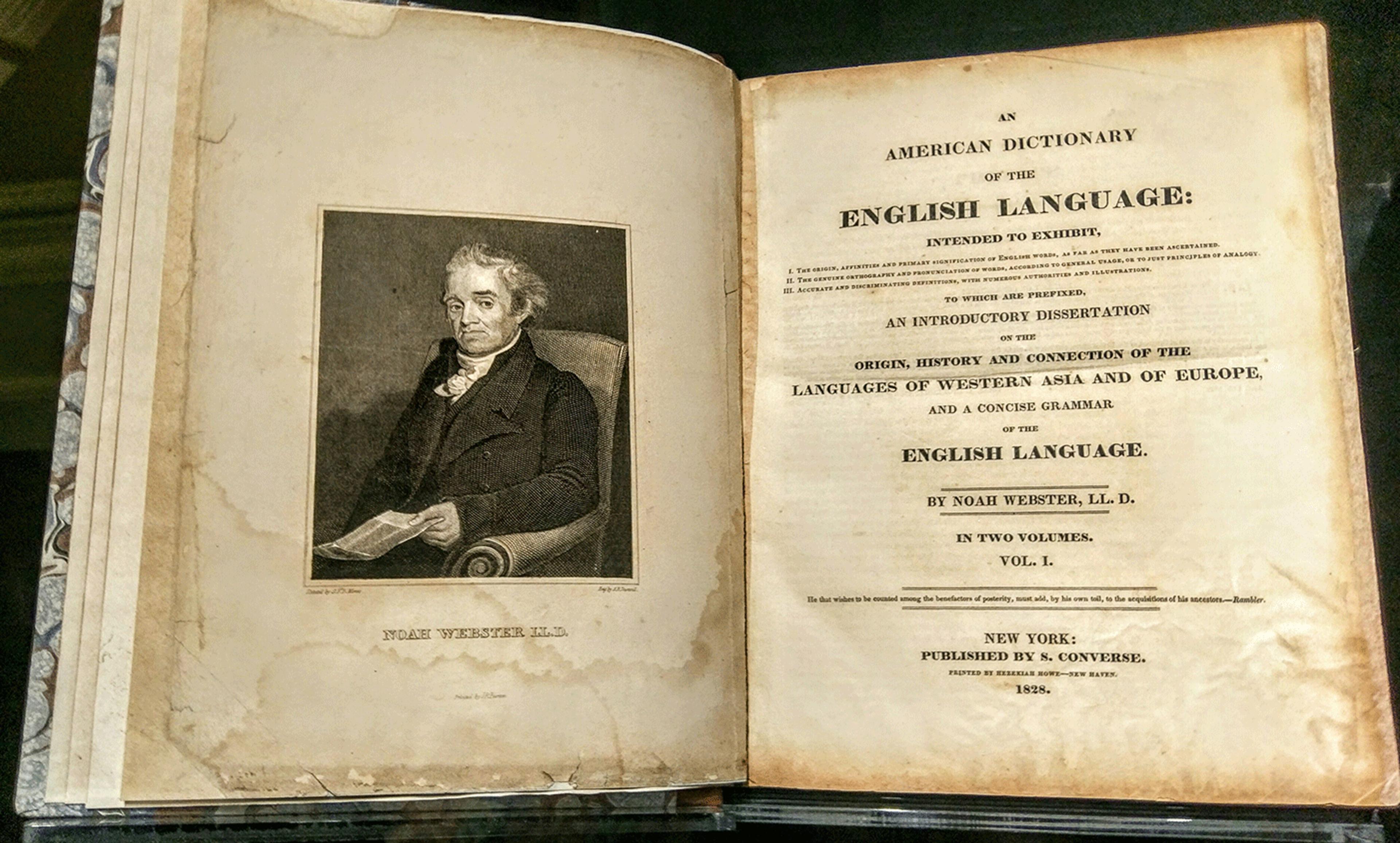

It is surely no accident that, just five years after Penn’s death, a young freethinker named Benjamin Franklin found a congenial home in Philadelphia. Penn might tower over Philadelphia from the top of City Hall, but Franklin surely remains the city’s most famous resident. Yet Franklin’s career is difficult to imagine without Penn’s foundational work envisioning a settlement in which one’s civic status did not depend on one’s religious affiliation. In 1984, the US president Ronald Reagan honoured Penn and his second wife Hannah with posthumous honorary American citizenship. A little late, perhaps, but still a recognition of Penn’s contribution. And for the record, that jolly face on the Quaker Oats box? Company officials insist that it belongs to someone called Larry, who has nothing to do with Penn.

Liberty, Conscience and Toleration: The Political Thought of William Penn (2016) and William Penn: A Life (2019) by Andrew Murphy are published via Oxford University Press.