Photo by Ahmad Odeh/Unsplash

I’m a lifelong dancer and a political theorist. ‘Work’ and ‘thinking’ in one part of my life are entirely physical, while in the other part they’re wholly intellectual. For most of my career, dancing and academic research were two separate but equally weighted spheres. However, over the years, I have become more and more aware that many people viewed dance as a less valuable way of thinking and working. Dance, in their minds, was a purely emotive activity consisting of uncritical, spontaneous movement or a purely athletic endeavour whose sole purpose is to defy our body’s physical limits.

Part of the reason why this view of dance persists, I think, stems from a deeply rooted prejudice against embodied vocations. In Aristotle’s ideal state in the Politics, for example, mechanics, farmers, shopkeepers and those living a banauson bion – a life of physical and menial labour – are excluded from full citizenship. Their modes of existence leave no time for leisure, yet their physical labour is essential to support those who carry out the deliberative actions of the city. Today, we continue to stratify work into ‘high-skilled’ and ‘low-skilled’ hierarchies. We wrongly presume that those whose work is primarily physical have little to contribute to those whose work is primarily mental, and vice versa.

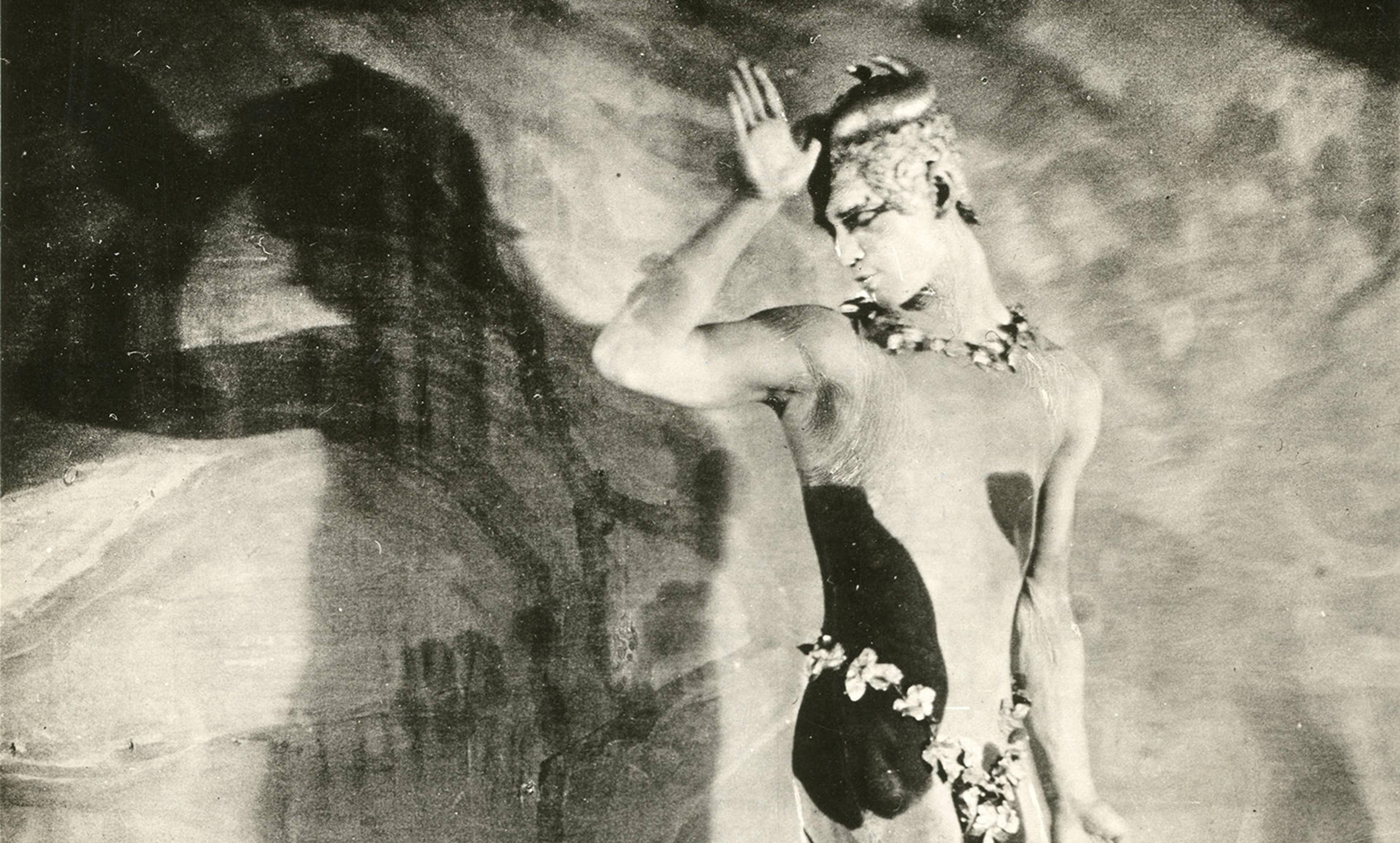

Dancers exist on the cusp of this prejudice. Our bodies are the primary instruments with which we absorb, distil and produce ideas that are intangible and ephemeral. But, in doing so, we are also seen as high artists. And it is precisely our highly trained capacity to combine physical with mental thinking that makes dance not only possible but powerful.

We dancers learn, maintain and teach what’s possible with physical expression. I, like many, began very young, and was quickly programmed into a world of rules, patterns and habits. Left hand on the barre to start, and always turn towards the barre to switch sides. Close in fifth position, but go through first. Front-side-back-side. Elbows, wrists, fingers; heel, arch, toes. As a dancer in training, you learn to dissociate your self from your body, to relinquish your agency to the structure and aesthetic of the form – whether that’s classical ballet, modern dance or something else. But treating dance purely as a physical form to which we subject our personhood is deeply problematic. As the American choreographer and dance writer Theresa Ruth Howard argues, it ‘romanticises the dehumanisation of the body by regarding it as an instrument, a tool akin [to] clay’. It turns our physical bodies into mere instruments for the ideas, beliefs and expressions from some external source – whether the teacher, the choreographer or even our own ideal of what the technique demands. Where, then, does the dancer find space for freedom, for individual agency in the strictures of this kind of physical practice?

The practice of cultivating agency and autonomy is essential to our physical and moral selves. I learned how to appreciate and respect agency relatively late in my dance career, but relatively early in my work as a political theorist. In 2013, I’d started graduate school and was continuing to dance and perform contemporary works, though the majority of my routine practice was in classical ballet. I had sustained multiple injuries and undergone a surgery. I became anxious that my body was past its prime, no longer suited to the demands of the art form, and that it was time to quit and find a different outlet. But a moment in a ballet class changed my mind.

Muriel Maffre, a former principal dancer at San Francisco Ballet and my then-ballet teacher at Stanford University, called our attention between combinations. ‘Dancers,’ she said, ‘get into the habit of breaking habits. Demonstrate you have agency over your body.’ There was only a brief pause before the accompanist gave us four counts before the battement-tendu combination started again, but the words resonated in my mind and my body for the rest of class. For most of my life, I believed that dancing consisted solely of building particular physical habits – habits that I could unthinkingly execute as soon as I crossed the threshold between the ‘real world’ and the dance studio. But Maffre’s admonition helped me see the wisdom in questioning and even undoing some of the habits, both physical and mental, I’d worked for decades to build. This didn’t mean that suddenly ballet itself – its organisation, combinations, its vocabulary and its grammar – was turned upside down. Instead, it meant that even the most technical, formal structures of the form had to be filled with my own agency.

I scrutinised my movements from the largest jumps to the tiniest gestures, wondering about their origins. An overextended port-de-bras in an arabesque – the iconic ballerina pose – puzzled me: it threw off my balance, but somehow I thought it looked beautiful. Where did the integrity of arabesque come from: my sternum, my standing leg, or my fingertips? Other times, things that manifested themselves as physical ticks or involuntary movements were actually within my control, but had a long physical history that I needed to investigate. I scrunched my toes too much, even when I didn’t need to balance. I premeditatively ‘fell’ out of an additional turn even though I had the physical power for one more revolution. And I thought I cast my gaze downward as a stylistic choice, but really I was checking out my feet. I started noticing and observing dance differently on my own body and on other dancers. The simplest movements, gestures and steps could convey such a wide range of textures, sensations and feelings. Tendus, I decided, were a display not of the arch of my feet but of the floor’s resistance. A renversé – my favourite step – was not just a shape I could make with my legs and arms, but an expression of my back body moving forward in space. Instead of striving for an appearance of weightlessness, I practised giving in to gravity and harnessing the power of my weightedness.

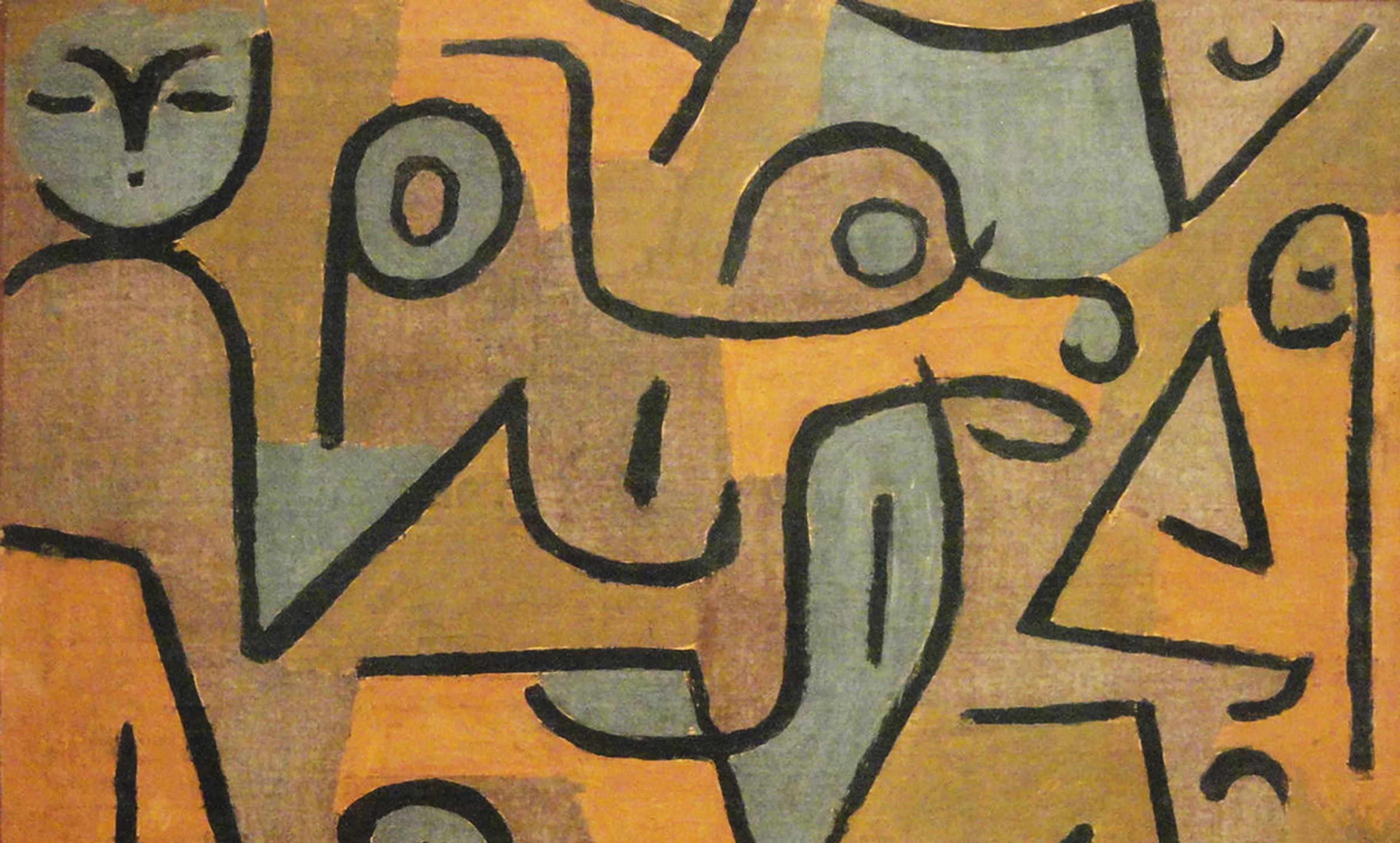

That all these qualities, which constituted the dancer’s artistry, were subject to choice inspired me. Dance, then, was my physical practice of independent and critical reflection – on received ideas, on formed habits, on the basic values and beliefs I held – not just about dance but also on what it means to be a flourishing human being. It was at that moment that I realised that my education as a dancer and scholar were converging and becoming inseparable ways of investigating ideas about personhood and the good life. The knowledge I acquired as a dancer physically expressed ideas about autonomy and freedom that I was investigating as a political theorist. My dance practice was an everyday, real and, above all, physical experience of what it means to have the capacity to direct one’s life, to be able to redirect it, and to see those capacities ‘as testimony of the strength rather than fragility’ of our fundamental personhood, as Rob Reich puts it in his book Bridging Liberalism and Multiculturalism in American Education (2002).

We learn by practice, the American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham once said. Our practices – both physical and intellectual – can be so much more than routine work and the accretions of habits. By choosing to perform the ‘dedicated precise sets of acts’ that we do, we can access ‘achievement, a sense of one’s being, a satisfaction of spirit’. We embody our autonomy and our humanity.