Courtesy PxHere

I am a flake of snow in a young girl’s Christmas dream. I leap and flit across the stage among dozens of fellow flakes. Our long skirts brush past each other as we twirl and whirl on the tips of our toes, sweeping our arms skyward. We move as one, effortlessly, to the gently lilting music. A slow sprinkle of confetti snow falls from above.

It must appear that the laws of physics and the limitations of the human body do not apply to us ballerinas. We are darting fairies eschewing gravity, swirling sylphs shunning inertia. But gravity is real and ballerinas are human.

I am a nervous teenager attempting to remember all the right moves in the right order so as to stay in step with the other girls. The tulle fabric of my skirt itches my legs. Sweat plumes under my arms and then begins to blossom on my forehead, threatening to reveal the acne hiding beneath a dense layer of stage makeup. My toes are blistered and bleeding. I smile as I choke on a mouthful of paper snow.

Pointe shoes are a strangely enduring anachronism that epitomises the enduring desire for ballerinas to embody the unnatural, to portray an illusion. And their intention as a tool to evoke ethereal beings is in direct contrast with their actual biological impact on very real humans.

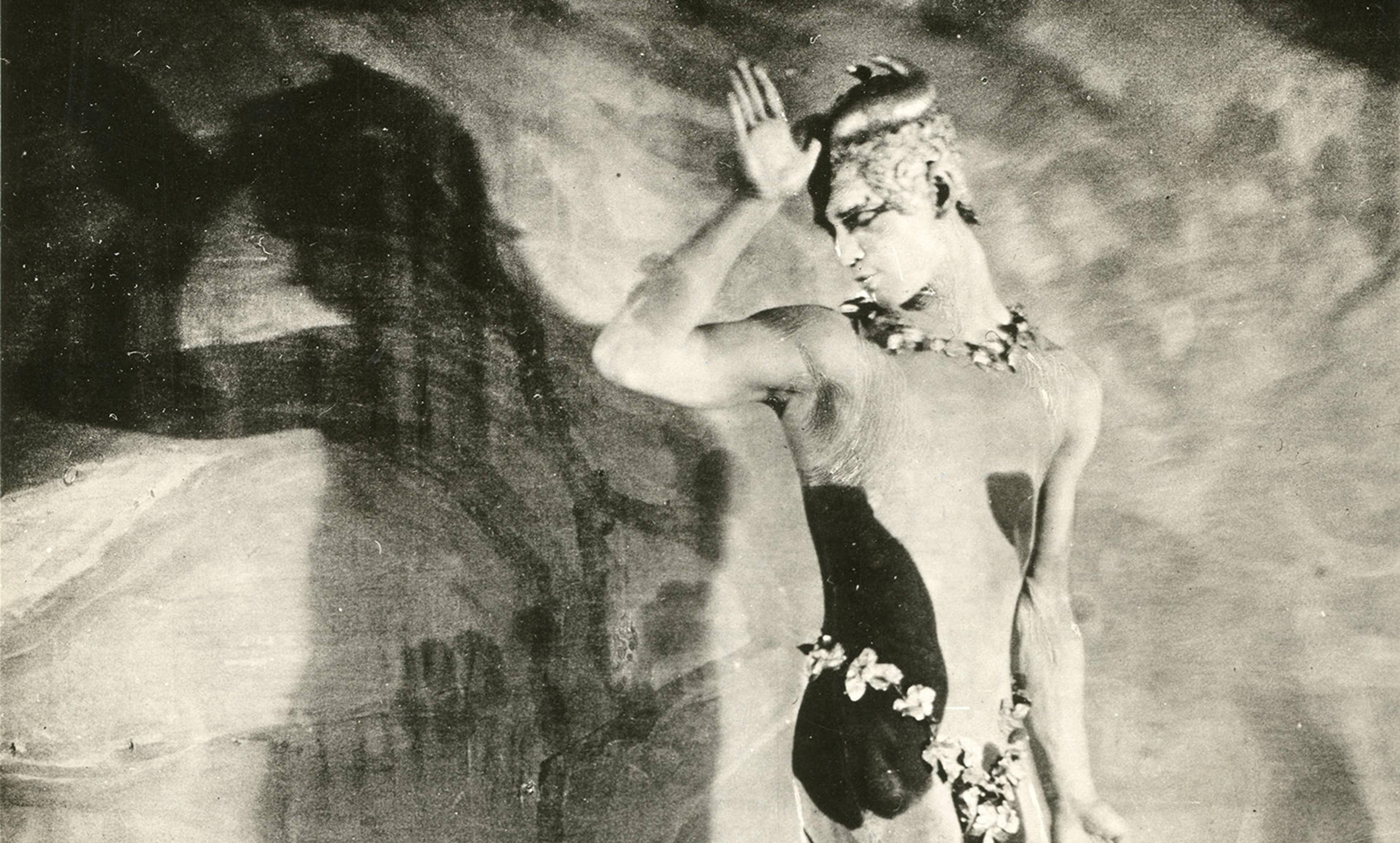

Like other transcendental themes explored in Romantic-era arts, pointe work in ballet began as a backlash to the mechanistic worldview of Newtonian physics. The roots of pointe can be traced back to 1794, when the French choreographer Charles Didelot used ropes and pulleys to lift his dancers just off the ground. Before that, dancers would occasionally rise beyond a ‘half pointe’ to a three-quarter pointe or fully on their toes without any type of special shoe as a sort of quick trick. One late-18th-century account describes a proto-pointe technique, in this case performed by a man, as appearing ‘to be supernatural’.

After initial success with audiences, Didelot improved his ‘flying machine’ and was soon the toast of the London performing scene. Pointe shoes meant that ballerinas could convincingly portray nonhuman characters: floating, hovering creatures in dreamy, fluffy skirts and wings. So many of ballet’s coveted main roles are nonhuman: swans, fairies, flowers, firebirds, butterflies, dolls, candy, ghosts, sylphs (flying supernatural spirits), Wilis (undead spirits who dance men to death). And these ballets are still some of the most popular performed today. As former dancer Ken Ludden writes in his 2014 book, Academy Method, on the history of pointe technique, the ballerina is ‘the symbol of beauty, nature, love, the supernatural, immortality. [She] is always depicted as a woman not bound to the earth, so dainty she can balance on a flower.’

Indeed, the Swedish dancer Marie Taglioni, who is credited as the first to dance a ballet en pointe when she starred in La Sylphide in 1832, had a flower set-piece crafted so that she could stand atop it. But it’s likely that she is merely the one whom history remembers as the first because her performance was so famous and she popularised the practice. In the journal Technology and Culture, Whitney Laemmli, a historian at Columbia University in New York, writes: ‘Already known for her uncommon delicacy and grace, Taglioni’s fame skyrocketed when she rose momentarily to her toes, fleetingly entering the titular sylph’s otherworldly realm.’

The pointe shoe too gained significant cultural cachet. Taglioni wore soft satin slippers with leather soles, whose sides and tips she darned to give them more support. But the first boxed-toe pointe shoe wasn’t used until 1841, by the Italian dancer Carlotta Grisi. Taglioni became such a celebrity that, after her final performance in Russia in 1842, her biggest fans apparently bought her used shoes, cooked them and ate them with sauce.

‘Today, the pointe shoe has lost little of that popular mystique,’ writes Laemmli. ‘The iconic footwear adorns the bedrooms of countless young girls, while the bloody feet of professional dancers are objects of widespread fascination … Nearly 200 years later, the Romantic-era links between the pointe shoe and the supernatural, the transcendent, and the effusively feminine are still strong.’

The phenomenon of female dancers as beyond the bounds of a human body is not just confined to the Romantic and early classical periods. With the Russian-born choreographer George Balanchine came ballerinas styled as geometry – essentially portraying objects. Dancers are abstractions: lines and angles making shifting shapes in three-dimensional space. In many of his ballets, female dancers simply wear a black leotard and pink tights. When they are characters, they are jewels or Greek statuary. It’s a stripped-down simplicity that shines the spotlight directly on the technical prowess of the dancer: what she can do with her body, how easily she can shun its apparent limitations.

Balanchine co-founded the New York City Ballet in 1948, but had been choreographing in Europe since the 1920s and in the US since the ’30s. His style favours speed, strength, musicality, flexibility, precision. His dancers were long and lean. They jumped higher and balanced longer and spun more rotations.

Early on, Balanchine sought the help of the Italian shoemaker Salvatore Capezio to make what would be the first major revamp of pointe shoes. Early pointe shoes boxes were made of heavy layers of fabric and glue, with shanks of leather and cork. Dancers stuffed lambswool or cotton padding inside under the tips of their toes. Balanchine thought these shoes too hard and heavy. His style demanded a softer, sleeker shoe. So Capezio crafted one that harkened back to the lighter Romantic-era shoes, one that required dancers to be stronger in order to use them.

These modern shoes, together with new technical demands, saw ballet dancers become true athletes: training for hours and hours a day, pushing and contorting their bodies to perform and perfect these predetermined shapes and movements codified in France hundreds of years earlier. For these performers, great effort is exerted to appear effortless. To trick audiences into seeing you as transcending your corporeal nature, you must indeed push your body past its natural limits.

Alas, there’s nothing supernatural, or even natural, about balancing all your body’s weight on two square inches. Compared with bare feet, merely walking around in pointe shoes more than doubles the pressure on the foot from 60 psi to 125 psi. The average pressure on the toes while standing en pointe is 220 psi. The big toe generally bears the brunt of this pressure.

In my 13 years of ballet training, I learned that the price of pushing the boundaries of biomechanics in the name of evoking the otherworldly is steep: I’ve endured joint surgery, broken bones, ingrown toenails, perpetual blisters. Even now, a decade after hanging up my dancing shoes, my hips still pop, my knees still strain from ‘turning out’. One by one, in my first years of dancing in pointe shoes, each of my toenails turned a shocking shade of eggplant and wilted off. I wonder if that ever happens to fairies.