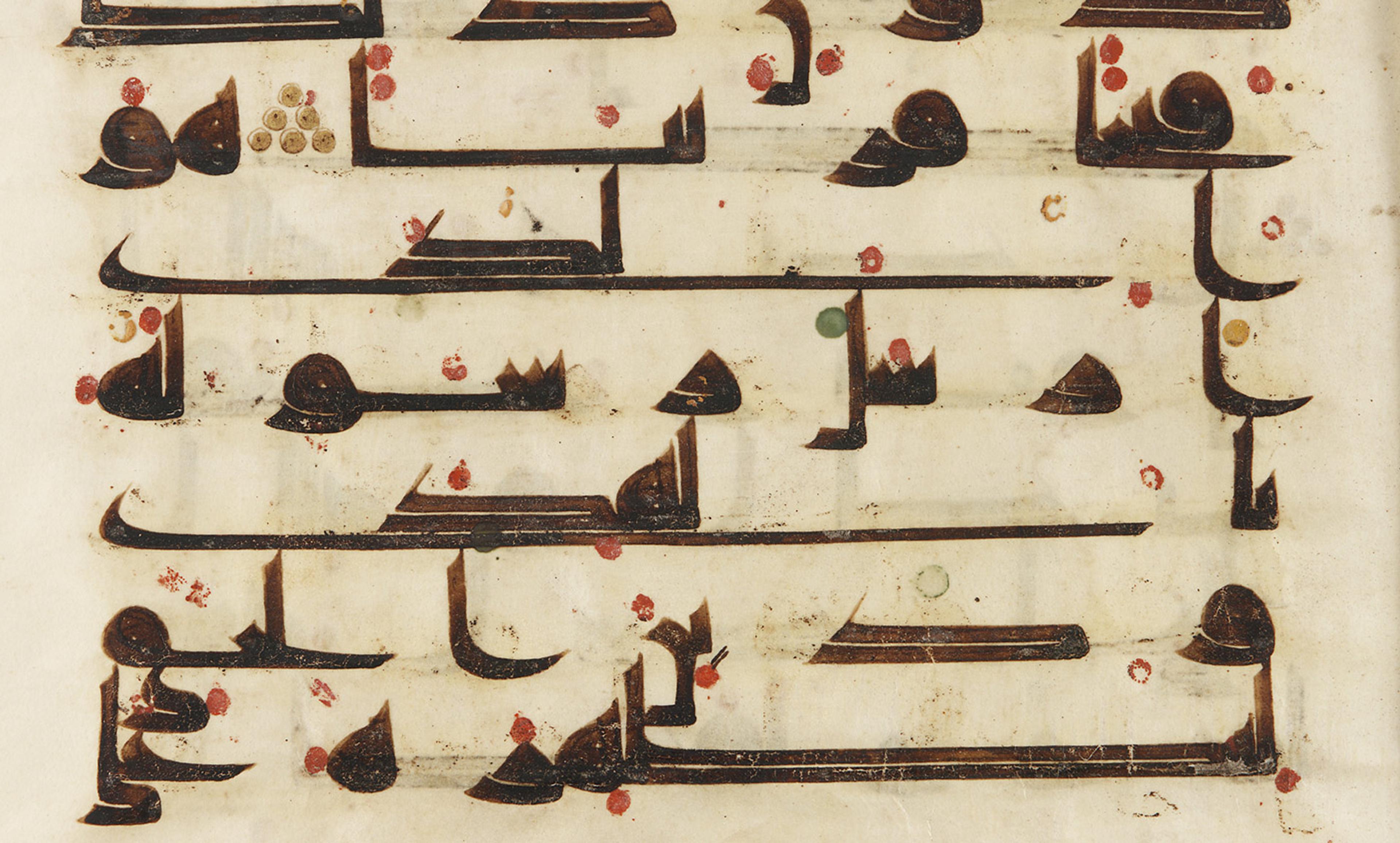

Quranic script from the 8th or 9th century. Courtesy Wikipedia

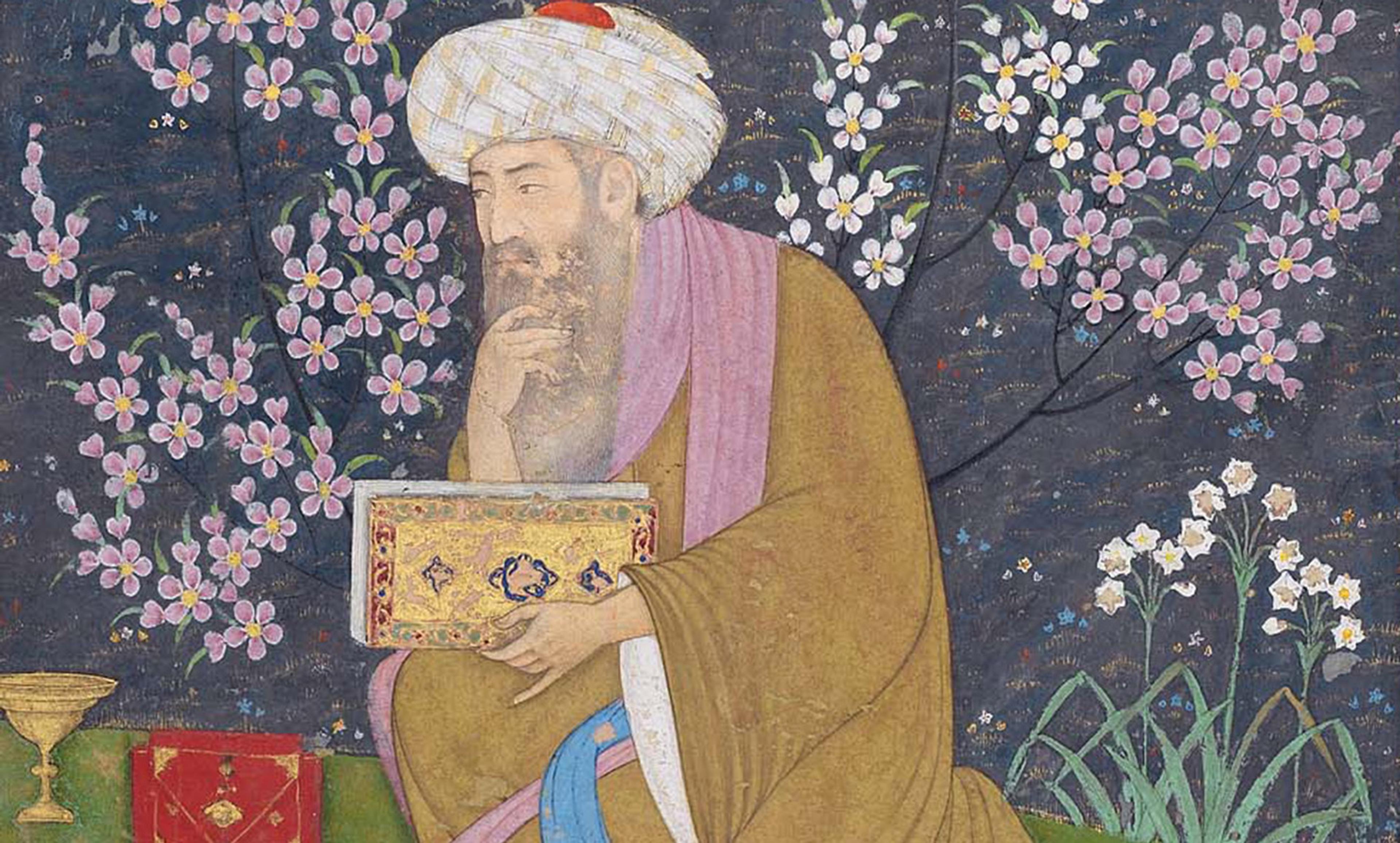

You might not be familiar with the name Al-Farabi, a 10th-century thinker from Baghdad, but you know his work, or at least its results. Al-Farabi was, by all accounts, a man of steadfast Sufi persuasion and unvaryingly simple tastes. As a labourer in a Damascus vineyard before settling in Baghdad, he favoured a frugal diet of lambs’ hearts and water mixed with sweet basil juice. But in his political philosophy, Al-Farabi drew on a rich variety of Hellenic ideas, notably from Plato and Aristotle, adapting and extending them in order to respond to the flux of his times.

The situation in the mighty Abbasid empire in which Al-Farabi lived demanded a delicate balancing of conservatism with radical adaptation. Against the backdrop of growing dysfunction as the empire became a shrunken version of itself, Al-Farabi formulated a political philosophy conducive to civic virtue, justice, human happiness and social order.

But his real legacy might be the philosophical rationale that Al-Farabi provided for controlling creative expression in the Muslim world. In so doing, he completed the aniconism (or antirepresentational) project begun in the late seventh century by a caliph of the Umayyads, the first Muslim dynasty. Caliph Abd al-Malik did it with nonfigurative images on coins and calligraphic inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the first monument of the new Muslim faith. This heralded Islamic art’s break from the Greco-Roman representative tradition. A few centuries later, Al-Farabi took the notion of creative control to new heights by arguing for restrictions on representation through the word. He did it using solidly Platonic concepts, and can justifiably be said to have helped concretise the way Islam understands and responds to creative expression.

Word portrayals of Islam and its prophet can be deemed sacrilegious just as much as representational art. The consequences of Al-Farabi’s rationalisation of representational taboos are apparent in our times. In 1989, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa sentencing Salman Rushdie to death for writing The Satanic Verses (1988). The book outraged Muslims for its fictionalised account of Prophet Muhammad’s life. In 2001, the Taliban blew up the sixth-century Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. In 2005, controversy erupted over the publication by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten of cartoons depicting the Prophet. The cartoons continued to ignite fury in some way or other for at least a decade. There were protests across the Middle East, attacks on Western embassies after several European papers reprinted the cartoons, and in 2008 Osama bin Laden issued an incendiary warning to Europe of ‘grave punishment’ for its ‘new Crusade’ against Islam. In 2015, the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine in Paris that habitually offended Muslim sensibilities, was attacked by armed gunmen, killing 12. The magazine had featured Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission (2015), a futuristic vision of France under Islamic rule.

In a sense, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas was no different from the Rushdie fatwa, which was like the Danish cartoons fallout and the violence wreaked on Charlie Hebdo’s editorial staff. All are linked by the desire to control representation, be it through imagery or the word.

Control of the word was something that Al-Farabi appeared to judge necessary if Islam’s biggest project – the multiethnic commonwealth that was the Abbasid empire – was to be preserved. Figural representation was pretty much settled as an issue for Muslims when Al-Farabi would have been pondering some of his key theories. Within 30 years of the Prophet’s death in 632, art and creative expression took two parallel paths depending on the context for which it was intended. There was art for the secular space, such as the palaces and bathhouses of the Umayyads (661-750). And there was the art considered appropriate for religious spaces – mosques and shrines such as the Dome of the Rock (completed in 691). Caliph Abd al-Malik had already engaged in what has been called a ‘polemic of images’ on coinage with his Byzantine counterpart, Emperor Justinian II. Ultimately, Abd al-Malik issued coins inscribed with the phrases ‘ruler of the orthodox’ and ‘representative [caliph] of Allah’ rather than his portrait. And the Dome of the Rock had script rather than representations of living creatures as a decoration. The lack of image had become an image. In fact, the word was now the image. That is why calligraphy became the greatest of Muslim art forms. The importance of the written word – its absorption and its meaning – was also exemplified by the Abbasids’ investment in the Greek-to-Arabic translation movement from the eighth to the 10th centuries.

Consequently, in Al-Farabi’s time, what was most important for Muslims was to control representation through the word. Christian iconophiles made their case for devotional images with the argument that words have the same representative power as paintings. Words are like icons, declared the iconophile Christian priest Theodore Abu Qurrah, who lived in dar-al Islam and wrote in Arabic in the ninth century. And images, he said, are the writing of the illiterate.

Al-Farabi was concerned about the power – for good or ill – of writings at a time when the Abbasid empire was in decline. He held creative individuals responsible for what they produced. Abbasid caliphs increasingly faced a crisis of authority, both moral and political. This led Al-Farabi – one of the Arab world’s most original thinkers – to extrapolate from topical temporal matters the key issues confronting Islam and its expanding and diverse dominions.

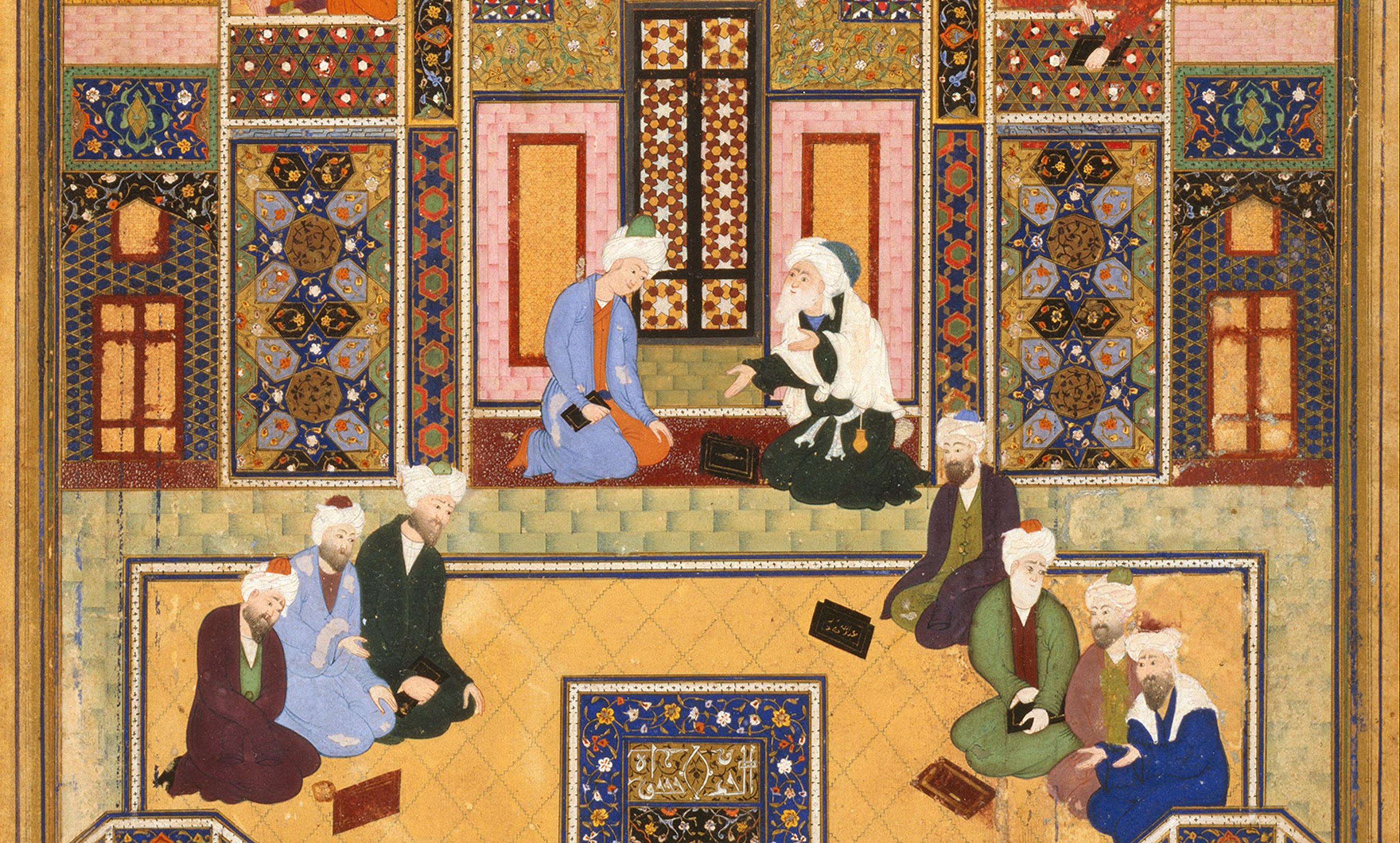

Al-Farabi fashioned a political philosophy that naturalised Plato’s imaginary ideal state for the world to which he belonged. He tackled the obvious issue of leadership, reminding Muslim readers of the need for a philosopher-king, a ‘virtuous ruler’ to preside over a ‘virtuous city’, which would be run on the principles of ‘virtuous religion’.

Like Plato, Al-Farabi suggested creative expression should support the ideal ruler, thus shoring up the virtuous city and the status quo. Just as Plato in the Republic demanded that poets in the ideal state tell stories of unvarying good, especially about the gods, Al-Farabi’s treatises mention ‘praiseworthy’ poems, melodies and songs for the virtuous city. Al-Farabi commended as ‘most venerable’ for the virtuous city the sorts of writing ‘used in the service of the supreme ruler and the virtuous king.’

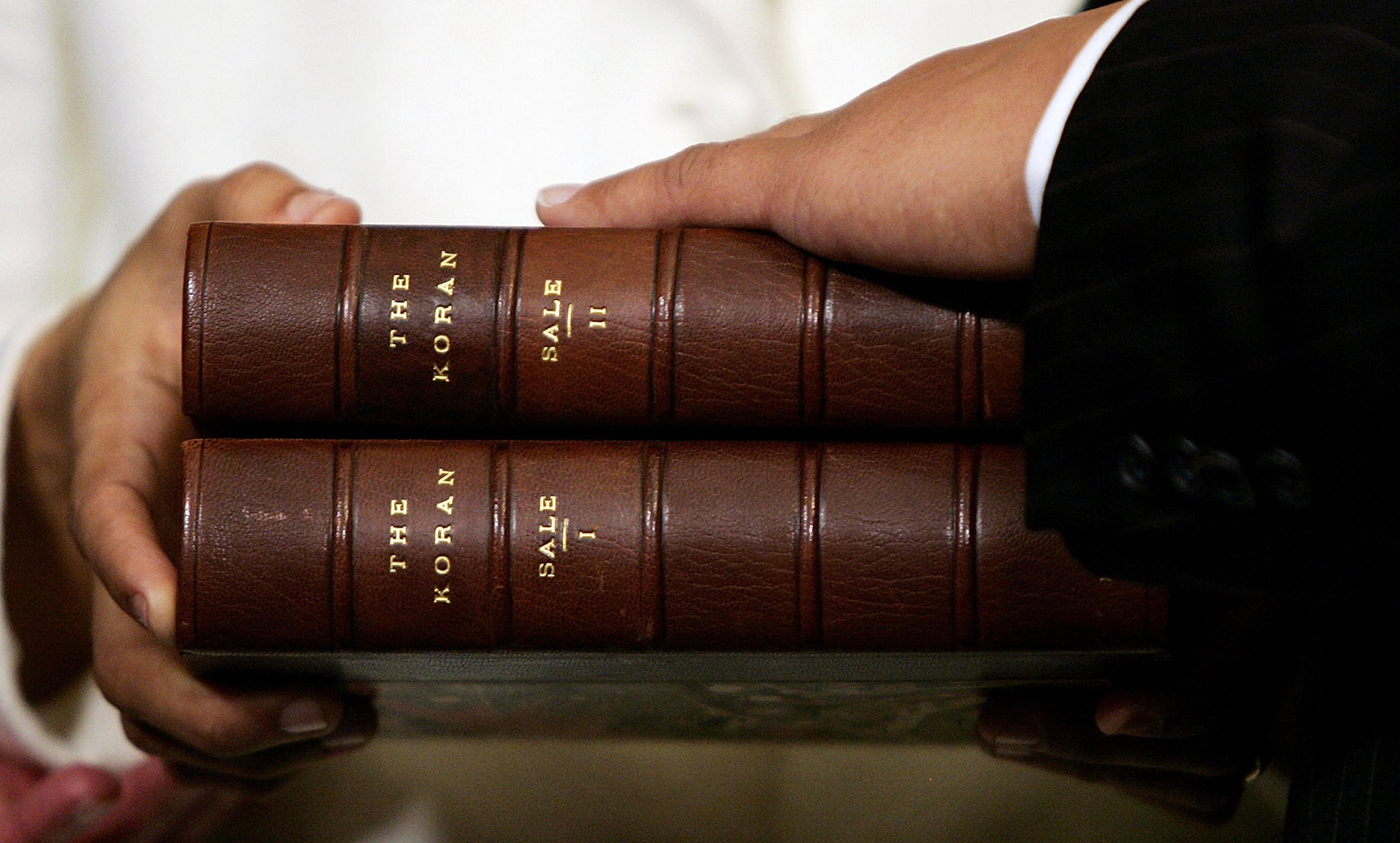

It is this idea of writers following the approved narrative that most clearly joins Al-Farabi’s political philosophy to that of the man he called Plato the ‘Divine’. When Al-Farabi seized on Plato’s argument for ‘a censorship of the writers’ as a social good for Muslim society, he was making a case for managing the narrative by controlling the word. It would be important to the next phase of Islamic image-building.

Some of Al-Farabi’s ideas might have influenced other prominent Muslim thinkers, including the Persian polymath Ibn Sina, or Avicenna, (c980-1037) and the Persian theologian Al-Ghazali (c1058-1111). Certainly, his rationalisation for controlling creative writing enabled a further move to deny legitimacy to new interpretation.