Fresco showing a skeptical-looking young man with a scroll labelled ‘Plato’, from Pompeii. Courtesy Wikimedia

I have published widely on Islamic political thought, including an encyclopaedia entry on the topic. Reading the Quran, Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), philosophy (falsafa) and Ibn Khaldun’s history of the premodern world, the Muqaddimah (1377), has enriched my life and thought. Yet I disagree with the call, made by Jay L Garfield and Bryan W Van Norden in The New York Times, for philosophy departments to diversify and immediately incorporate courses in African, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American and Native American ‘philosophy’ into their curriculums. It might seem broadminded to call for philosophy professors to teach ancient Asian scholars such as Confucius and Candrakīrti in addition to dead white men such as David Hume and Immanuel Kant. However, this approach undermines what is distinct about philosophy as an intellectual tradition, and pays other traditions the dubious compliment of saying that they are just like ours. Furthermore, this demand fuels the political campaign to defund academic philosophy departments.

Philosophy originates in Plato’s Republic. It is a restless pursuit for truth through contentious dialogue. It takes place among ordinary human beings in cities, not sages and disciples on mountaintops, and it requires the fearless use of reason even in the face of established traditions or religious commitments. Plato’s book is the first text of philosophy and a reference point for texts as diverse as Aristotle’s Politics, Augustine’s City of God, al-Fārābī’s The Political Regime, and the French philosopher Alain Badiou’s book Plato’s Republic (2013). The British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once said that the history of philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato. Even philosophers who do not mention Plato directly still use his words – including ‘ideas’ – and his general orientation that prioritises truth over piety. Philosophy is the love of wisdom rather than the love of blood or country. It is in principle open to everybody, and people all around the world heed Plato’s call to live an examined life.

I am wary of the argument, however, that all serious reflection upon fundamental questions ought to be called philosophy. Philosophy is one among many ways to think about questions such as the origin of the Universe, the nature of justice, or the limits of knowledge. Philosophy, at its best, aims to be a dialogue between people of different viewpoints, but, again, it is a love of wisdom, rather than the possession of wisdom. This restless character has often made it the enemy of religion and tradition.

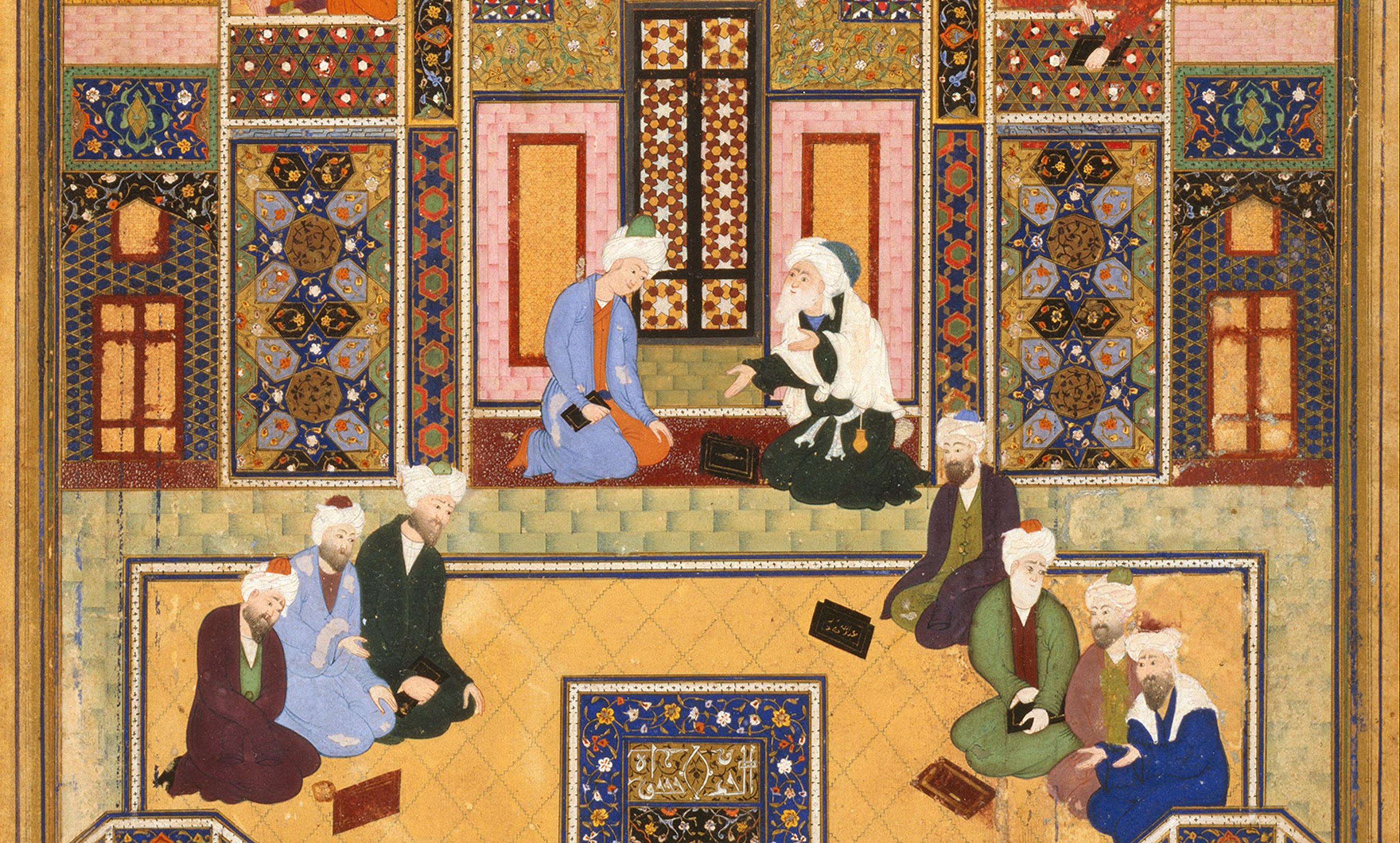

Consider the outlook of Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058-1111), a towering figure in Islamic thought. In Deliverance from Error, al-Ghazali recounts his time reading Plato, Aristotle and their ostensibly Muslim readers. He asserts: ‘We must reckon as unbelievers both these philosophers themselves and their followers among the Islamic philosophers, such as Ibn Sina, al-Farabi and others.’ Al-Ghazali recommends that Muslims ‘shut the gate so as to keep the general public from reading the books of the misguided as far as possible’. Even though he himself makes philosophical arguments, he does not want to enter the tradition of falsafa and is widely credited with trying to end this tradition with books such as The Incoherence of the Philosophers. If one wants to study Islamic political thought in the centuries after al-Ghazali, scholars should primarily study theology (kalam) and jurisprudence (fiqh), not falsafa.

Likewise, Confucius (551-479 BC) might be worth reading, but it stretches terms too far to call him a philosopher. In The Analects, ‘The Master said, “When someone’s father is still alive, observe his intentions; after his father has passed away, observe his conduct. If for three years he does not alter the ways of his father, he may be called a filial son.”’ Confucius presents a comprehensive doctrine of a good life that includes filial piety and respect for elders. By contrast, in the opening pages of the Republic, Socrates ridicules the old man Cephalus for his poor understanding of the meaning of justice. Plato’s message is that philosophy has no patience for elderly people who like things the way they are and don’t want to wrestle on the terrain of ideas. For the Confucian, Plato’s defence of critical thinking might seem like a recipe for family strife and social disharmony.

I doubt that philosophy departments are the natural home for scholars of Islamic jurisprudence or Confucian ethics. Philosophy departments support the teaching and research of logic (the rules of thinking), metaphysics (the study of being), epistemology (the theory of knowledge), aesthetics (the study of art), ethics (the investigation of personal morality), and politics (the pursuit of justice). Philosophy as an academic discipline has consistency insofar as it originates from the Socratic-Platonic tradition. Should philosophers converse with scholars of different religious and moral traditions? Of course. But it makes little sense for philosophers, say, to become amateur Islamic jurists or for Quranic scholars to study philosophy as a prerequisite for their doctorates.

To understand why the limits of philosophy matter, we need to situate the debate within ongoing debates about the funding of higher education. Last year, the Republican senator Marco Rubio said: ‘We need more welders than philosophers,’ a blunt articulation of a widely shared view among taxpayers and policymakers looking for reasons to eliminate, cut or defund philosophy departments. In that New York Times op-ed, philosophy departments are accused of being ‘temples to the achievement of males of European descent’. The implication is that academic philosophy is racist, sexist and worthy of an imminent demise. This will be welcome news for policymakers who want to prohibit federal funds from subsidising the study of philosophy, say, at community colleges or state universities.

As someone who loves to read, study and, on occasion, do philosophy, I would consider this a tragedy. Let philosophy departments evolve organically as scholars convince their peers that a new author, idea or tradition is worth engaging. And encourage universities to explore ways to broaden their scopes of inquiry to learn about other intellectual traditions. But demanding that philosophers treat al-Ghazali or Confucius as one of their own is unreasonable, and provides ammunition to people who are ready to banish philosophers from their midst.