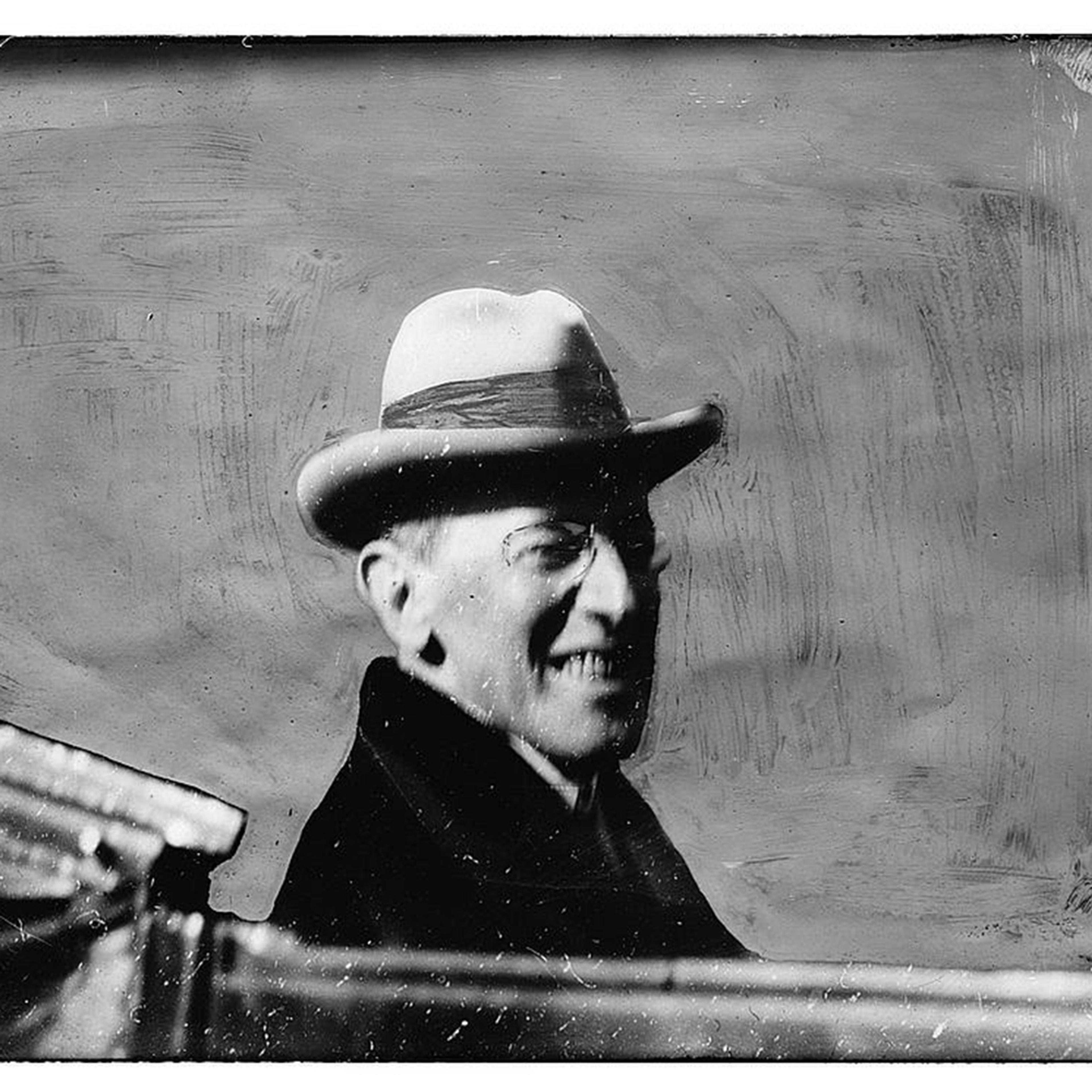

A formal dinner at Magdalene College, Cambridge. Photo by Martin Parr/Magnum

Benedictus, Benedicat, per Jesum Christum, Dominum Nostrum. Amen.

Please be seated. It’s dinner time in St Paul’s College, Sydney, where I’m dean and head of house at Graduate House. The members of the High Table, wearing academic gowns, have processed into the refectory to a table laden with candelabra and silver accoutrements from the college treasury, each place set with cutlery and glasses. The students, also in gowns, rise from their seats to acknowledge the High Table, and stand until the presider has finished the Latin grace (this is the shorter one – a longer version is kept for feasts). Now that all are seated, a three-course meal is served, accompanied by poetry, music, announcements and general well-dressed merriment. Port is served. A final grace is said after dinner, then all retire to the common room for coffee (or more port) and further conversation. The men wear ties. The women dress up. Diners bow to the High Table when excusing themselves, and the High Table bows back when departing from dinner.

This is, by no means, an entirely unique ritual. Everywhere the British empire planted its flag, its two great universities of Oxford and Cambridge spread their collegiate model, and so Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States all have their colleges, each with their traditional ways of dining and living. St Paul’s is the oldest such college in Australia, but it’s different from the others (and from those in Britain) in a significant respect. St Paul’s contains two communities – undergraduate and postgraduate – each with their own buildings, dining halls, common rooms, and leadership; each almost a college unto itself, but joined in many endeavours. The undergraduate community was founded in 1856, and Graduate House, which I lead, in 2019. Yet, despite this difference in antiquity, the description above describes dinner in either community, every week.

When I started as dean of Graduate House, there was no Graduate House, only an incomplete construction site and an idea. My brief was to recruit the students and academics, fill the buildings with people, set up student leadership, and design and define the culture and practices of a new college-within-a-college.

I didn’t want for unsolicited advice. The most common sentiments I heard were unsurprising: ‘a new college can be modern’, ‘you don’t need gowns’, ‘you don’t need formal dinner’, ‘graduate students in a new college will want it casual!’

We wear gowns. To formal dinners. It is not casual. It is not ‘modern’.

I hold an unpopular view. I believe, firmly and invariably, that life in the 21st century is too informal and empty of ritual, and that we should encourage and erect more needless formality. Formality, ritual and ceremony – not casual approachability – are among the most effective ways of making the world and its institutions more inclusive and egalitarian. We all need much more formality in our lives.

The past century has been a good one for individual freedoms – in almost every respect. This wholesale liberalisation has included the freedom of individuals to dress, dine and discourse how they like it. And how they like it is invariably: ‘casual’, ‘low key’, ‘without too much fuss’, ‘not too precious’, ‘not too pretentious’, ‘not ostentatious’ or, as I heard just the other day, ‘not too “bougie”’ (qua ‘bourgeois’)… in short, informal. Comfort is king in the modern world; and comfort is the excuse proffered for the evaporation of formality from daily life.

While formality and its rituals persist in little pockets, they do so only where they are bolstered by elaborate protective struts. In general (though decreasingly), government ceremonies remain somewhat formal. With ever increasing exceptions, weddings and funerals cling to formal traditions. The High Church has positioned itself as the last refuge of formal practice – a claim that would have no teeth had not the Low Church so effectively abolished the bells and smells and hymns and ceremony in favour of appealing to parishioners who want a service that ‘isn’t too fussy’.

Comfort has won, and most formality is gone. But the freedom of informality comes at a cost. Formality is the bulwark against some of the nastiest human impulses, and acts as a vaccine against our most dangerous tendency: forming in-groups and out-groups.

There’s nothing you or I or the Pope or the United Nations could do to stop humans from forming clubs, inventing or elevating meaningful markers of difference, and building fences and corrals that keep one’s group together while keeping the ‘others’ out. We are a tribal ape with a brain built to exaggerate our allegiance to our small band while manning the barricades against others distinguished by vanishingly tiny differences. Individuals can, with great effort, consciously suppress this nasty bit of programming, but populations on the whole will fail.

Groups can form around any distinguishing feature, from the harmless, such as sporting teams, schools attended or favourite novels, to the nefarious, such as race, class or sex. Each person can disavow some marks of difference while clinging to others – and no person can disavow them all.

This mental virus might be incurable, but there is a vaccine: formality. Formality gives us something harmless around which to form an in-group: namely, knowledge of the rules of that particular formality, with its own trials of membership and rules of initiation.

‘Ah yes, the dress code is a bit difficult to understand… You see, it’s based on Edwardian standards, of course, so “semiformal” actually means black tie! No, no, don’t worry a bit, it is unusual…’

The opportunity to be a crowing pedant about the rules of formality gives one something to do instead of in-grouping around more exclusionary traits, such as to which expensive school one went. More importantly, the rules of formality are ultimately accessible to all. Anyone can learn the etiquette and wear the tie, and so become part of the ever larger, ever more diverse in-group that practices the formality of the event.

The livery companies of the City of London are some of the more formal and traditional institutions in the United Kingdom today; formal dinners, ceremonies in Tudor (or mock-Tudor) garb, and incredibly convoluted elections are their standard fare. Despite their finery and antiquity, they aren’t – nor have they ever been – aristocratic. More than a century ago, they were already associated with upwardly mobile plebs, so much so that Gilbert and Sullivan poked fun at the House of Lords’ collective disdain for the Common Council (composed of many livery company members) in their comic opera Iolanthe (1882). The companies began as workmen’s guilds and preserve those class associations, but they are formal, traditional organisations, because this helps to bind their members together, despite their differences, making them all feel as one.

This is a common pattern. While the London gentlemen’s clubs are well-dressed and traditional, they’re largely devoid of ceremony; instead, they’re well-appointed places to relax over meals or drinks and sniffingly observe shibboleths of the upper classes, from which syllable to stress in ‘patina’, to why one ought not to own fish knives. Meanwhile, foundationally working-class clubs, such as the Knights of Columbus or the Freemasons, deck themselves in formal ceremony and ritual. The already powerful can afford not to make too much fuss. For the up-and-coming, or the downtrodden, formality gives an unparalleled sense of membership to a grander body.

Universities and colleges once knew this well. They remain some of the only institutions still using formality to their advantage, though often grudgingly and falteringly. I lived and worked in a number of colleges in Oxford before moving to Australia, and watched as various members of the leadership tried – sometimes successfully, sometimes not – to strike away little elements of salubrious formality, when they felt the striking was good. And so, dinner’s fourth course went, but second dessert was preserved. Another night of the week became informal, but Sunday was still black tie. They chip away at traditions, forgetting that, for students, visiting fellows and new academics, these are the very things that cause rapture and delight.

In 2019, it was an act of fortitude to stand before 100 newly enrolled graduate students – mostly Australian, few with any experience of an ancient college – and insist that in this brand-new, modern building, at our very first dinner, we would wear academic gowns, say grace in Latin, and pass decanters to the left. It was harder still to say the same to a dozen busy and seasoned academics who joined us. But it was the right choice, and the college is better for it. In this modern university, my students and academics come from every political, religious, social and economic background one can imagine; they don’t have anything extrinsic in which to believe together. College gives them something to believe in as a whole.

The college needs ritual, tradition, anachronism and whispers of the numinous to bind together this diversity. Not to smooth it out, but to unite it in true engagement. Any apartment building can fill itself with diverse residents who politely acknowledge each other in the hallways, then keep to themselves. It takes a formal, traditional, ritual-filled ancient college to make them all feel as though they’re truly of one kind – even if that ancient college is only a year old.

Benedicto, Benedicatur, per Jesum Christum, Dominum Nostrum. Amen.

Postscript: This Idea was conceived and written in early 2020, in a time when COVID-19 was but a suppressed whisper. Reading it now, when ceremony and togetherness are rightly halted for the good of global health, feels like reading a dispatch from a different world. But I do hope this crisis, which is, underneath the medical crisis, a social one, will provide a chance for reflection on how we interact, and that a global community resuming its usual business will embrace the opportunity to repair our broken institutions of formality and ceremony. In short, I hope we all come out of quarantine wearing our Sunday best, ringing bells, lighting candles and burning incense.