An infant is born. The radiant mother holds the baby in her arms and immediately begins to scan the infant’s face, softly caressing the little fingers while uttering repetitive sing-song vocalisations, her face lighting up in an affectionate smile. She has never had a baby before but intuitively knows what to do. Proud and oblivious, she feels no one has ever cared for such a gorgeous child; yet she stands along a great line of mammalian mothers who lick, groom, sniff, smell, touch, poke, nurse and handle. Rats do it, sheep do it, even educated chimps do it … let’s fall in love.

Behind our loving mother, evolution works with its quick-and-dirty tools to ensure the bond is cemented, the infant finds the nipple, the mother engages; brain meets the world. The synchronous dance of mother and child begins and, upon its unique rhythms, a relationship is formed. This relationship will incorporate, like expanding ripples, the child’s emerging abilities across development and into dialogue: babbling, creating imaginary scenarios, the capacity to collaborate, feel the pain of others, comprehend emotions, discuss conflicting positions, argue convictions, until the child grows and can meet the mother in a full adult-to-adult relationship of empathy, intimacy and perspective-taking. Like the 12-bar-blues, synchrony gains in range, repertoire, complexity and timbre, but its basic rhythms stay safe and secure.

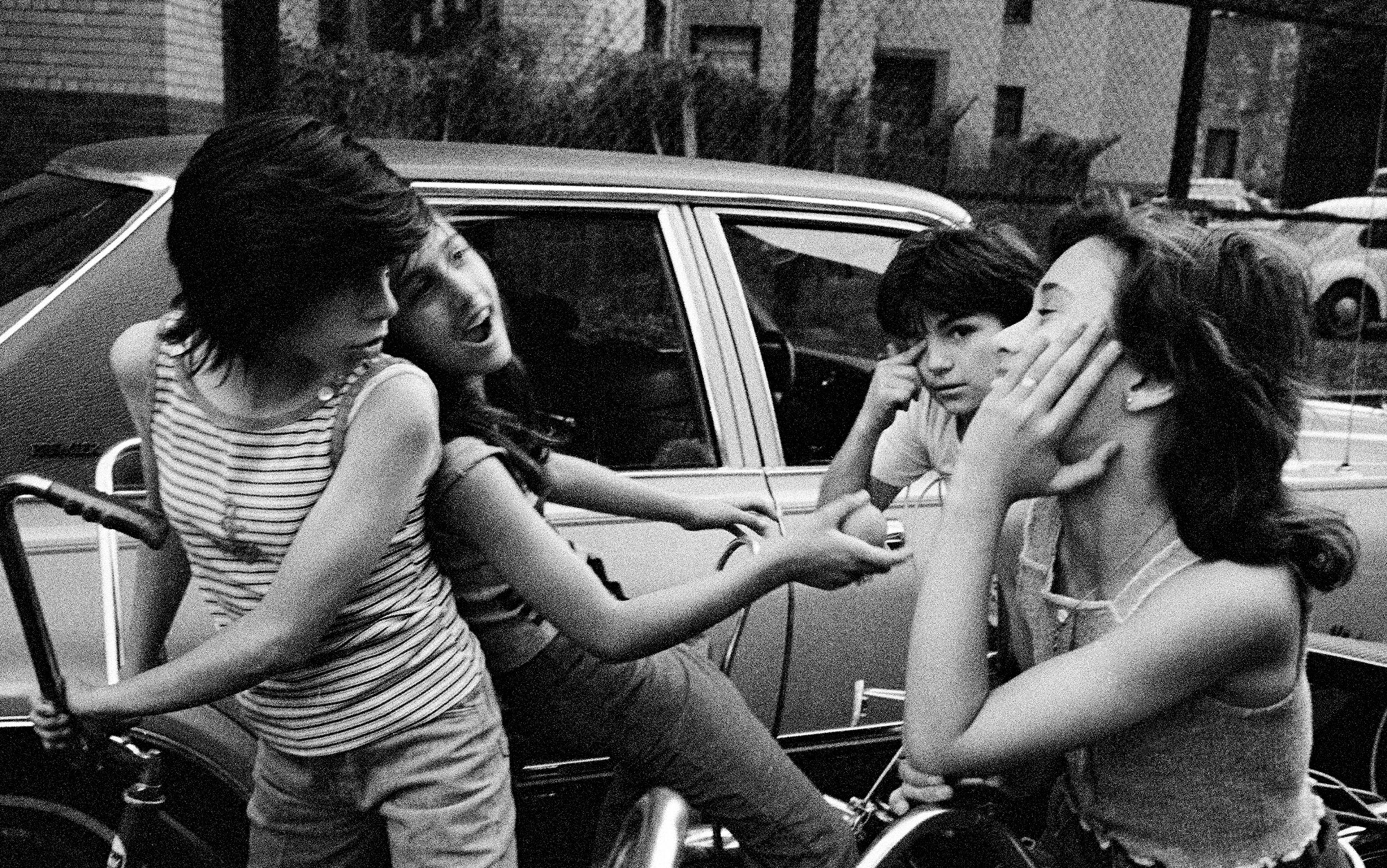

The synchronous mother-infant dance will set the stage for the child’s affiliative bonds throughout life: with father and siblings at home, with close friends in school, through adolescence and first love and, finally, as parents to children of their own. Those affiliations, and the terms of endearment they set, will guide the child’s conduct within society-at-large, shaping the empathy, responsibility, collaboration and self-restraint by which he or she will meet fellow-humans: co-workers, neighbours and strangers.

Evolution is thrifty, and once a trick works, it will be repurposed endlessly. A new mother and infant enter the world tapping the social patterns, habits, beliefs, customs, fears, hopes, joys and rituals of the old ones. The family, the group, the tribe lives on from one generation to the next. Resilience, endurance and the durability of the group can be achieved only by coordinating action among kin, first genetically and then symbolically. Infants acquire the capacity for coordinated action in the context of the mother’s body and its unique provisions: a mother’s smell, touch, heart rhythms, eye-gaze, smile. Then it expands across time, place and person. But such massive expansion does not come without its risks.

What tricks of the trade does evolution utilise to ensure that bonding, so critical for survival and continuity of life on Earth, happens as planned and all pieces of the puzzle fall safely into their place? After decades following thousands of mother-infant dyads, hundreds from birth to young adulthood, my lab has mapped the ‘neurobiology of affiliation’ – the emerging scientific field that describes the neural, endocrine and behavioural systems sustaining our capacity to love. The foci of our research – the oxytocin system (based on the neurohormone of bonding); the affiliative, or social, brain; and biological synchrony between mother and child – are all marked by great plasticity, and sculpted throughout animal evolution to reach their exquisite complexity in humans. And they all lean on automatic and ancient machinery that runs the risk of turning love on its head into fear.

Oxytocin, the first element in the neurobiology of bonding, is an important driver of both care and prejudice. A large molecule produced mainly by neurons in a small region of the brain called the hypothalamus, oxytocin is known for coordinating bonding, sociality, and group living. From the hypothalamus, oxytocin targets receptors in the body and the brain, primarily the amygdala, a centre for fear and vigilance; the hippocampus, where memory resides; and the striatum, a locus of motivation and reward. Through these pathways, the bonding hormone, oxytocin, functions with the precision of a neurotransmitter and the longevity of a hormone, reaching faraway locations and broadly influencing behaviour. Importantly, oxytocin is released not only through the central part of the neuron, but also its extensions, called dendrites. The dendrites are primed to increase oxytocin release whenever attachment memories are invoked. This way, early attachments prime us for a lifetime, and we keep seeking echoes of early experiences in later relationships, whether being carried on mother’s back throughout the day or exploring nature with father.

Memory of these early attachments helps us re-enact the unique state that Sue Carter, a neurobiologist at the University of Indiana, calls ‘immobility without fear’. These same memories enable what the English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott in 1958 described as ‘the capacity to be alone’ in the presence of someone in a state of peace, serenity and transcendence, where aloneness is not loneliness. In our studies, we found that, throughout life, during periods of bond-formation – for instance, when we fall in love or form a close friendship – oxytocin production increases to cement the new bond, as it does at birth. During birth, a surge of oxytocin triggers uterine contractions, and oxytocin release initiates milk letdown. Maternal oxytocin is then transferred to the infant through the mother’s milk, touch and caregiving behaviour. It bonds mother and child forever but it also reorganises the infant’s brain to what it means to be in love and what it takes to feel safe. This is how cultures ‘stamp’ the infant’s brain with the distinct social patterns that reflect their philosophies on human relationships, particularly those across the generational divide – for instance, are adults and children allowed to be in direct eye contact and dialogue as equals?

The same oxytocin that supports love and kindness also underlies prejudice and parochialism

Still, oxytocin is an ancient system that functions in a quick-and-dirty way; no time for complexities when the lion is at your door. The oxytocin molecule presumably evolved approximately 600 million years ago, and is found in all vertebrate and some invertebrate species. Its role across animal evolution was to help organisms manage life in harsh ecologies. Hence the system supports regulation of basic life-sustaining functions: water conservation, thermoregulation or energy balance in species such as nematodes, frogs or reptiles.

With the evolution of mammals, oxytocin became integrally involved in controlling birth and lactation; as a result, the young acquired life sustaining functions and skills not in the context of the group but within the intimacy of the mother-infant bond. This created the main schism I wish to underline, the core conflict of the human condition: mammals learn to manage hardship through relationships, and bonding is their key mechanism for stress reduction. Being born a mammal, then, implies that oxytocin, the very system that sustains parental care, pair-bonds, group sharing, and consoling behaviour, also became intensely sensitive to danger. Oxytocin protects against danger by immediately differentiating “friend” from “foe” based on nuances of social behaviour.

When mammals perceive slight alterations in social behaviour, they identify the approach of ‘others’, activating the alarm systems of the fight-or-flight response and their bodies prepare to attack. Those ‘others’ may indeed intend to eat us up for supper, or they could just as readily be going about their daily social life in ways that seem to us odd, unfamiliar, or even disrespectful. They could be like the ‘enemies’ Dr Seuss describes in The Butter Battle Book, a parable about the Cold War: ‘those who eat their bread with the butter side down’. But when the stakes are so high, why take a chance?

Through it all, the oxytocin system is integrally involved. Oxytocin neurons stand in close proximity to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-producing stress-sensitive neurons in the hypothalamus. Human studies, both ours and others, have repeatedly shown that the same oxytocin that supports love and kindness, also underlies prejudice, parochialism, and outgroup derogation, even when the ‘outgroup’ comprises those who wear a blue shirt while the ‘ingroup’ wears red.

The second element in the neurobiology of bonding is the affiliative brain. Research into its role in maternal care began in the 1950s with the work of Jay Rosenblatt at Rutgers University-Newark in New Jersey and colleagues, who wished to chart the brain structures that enable rodent mothers to care for their offspring. Following decades of careful work by several research groups, the scientists were able to describe the ‘mammalian maternal brain’ both in terms of its neural networks and, more recently, their molecular composition. Primed by oxytocin’s increase during pregnancy, the hypothalamus (specifically, the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus) sends projections to the amygdala, and this sensitises an oxytocin-amygdala ‘line’ that makes mothers extremely attuned to signs of infant safety and danger. This line of constant vigilance and worry is implanted into the maternal brain as soon as an infant is born and, without it, our fragile offspring might not survive.

In human mothers, the amygdala activates four times more than in fathers: from the moment of birth and, I believe, forever thereafter, mothers sleep with their amygdala open. Imagine this: a 15-year-old goes to a party. You trust her, have arranged for your best friend to pick her up, and know who she’s with. You go to sleep, but your amygdala is open. It is 3am and you hear the door open and her footsteps tiptoeing in. You turn to the other side and finally sleep in earnest. The ‘care’ and the ‘scare’ become inseparable the minute you love someone for real. It is precisely this entanglement that defines, in my mind, the ancient curse: ‘In sorrow thou shalt bring forth children’ – not the birth itself, which we soon forget due to the analgesic properties of oxytocin.

Yet, at the same time that the tracks for the oxytocin-amygdala line are set, the oxytocin-primed hypothalamus sends another projection, this time to the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the brain’s dopamine factory, and the striatum, where dopamine receptors abound, to make the infant the most rewarding stimulus for its mother. The infant’s smell, soft skin and cute round face become addictive, and mothers can spend hours looking at, sniffing and licking their baby. Even infant reminders become imbued with reward: the pacifier, the crib, the nursing chair all trigger the brain’s reward system and initiate a state of bliss. Our lab found that it is enough to put a picture of an unfamiliar infant on a side screen when parents discuss a conflict to quiet their sympathetic arousal, decrease their hostile tone, and increase their empathic concern for each other.

The evolutionary role of the oxytocin-dopamine line is to ‘glue’ the mother to her baby so she can tolerate the sleepless nights, physical pain and endless mess. This oxytocin-dopamine line is even engraved into the neurons. The nucleus accumbens, a node in the striatum, contains neurons that encode both oxytocin and dopamine, enabling the brain to combine the motivation and vigour of dopamine with the social focus of oxytocin in order to set the parent’s – and, via the cross-generational cycle, the infant’s – reward system for a lifetime of longterm attachments. When the connection between oxytocin and dopamine breaks, results are devastating. When dopamine is directed to neural targets unrelated to sociality, a risk is addiction; when dopamine and oxytocin are produced out of synch, depression can result.

A neurological triangle, including the oxytocin-producing hypothalamus at the top for sociality and the two arms of ‘scare’ and ‘bliss’, underpins mammalian mothering. In species where mother and father parent together, this same system also supports paternal care, and recent molecular studies show that mothering and fathering are underpinned by the same brain structures, though with different populations of neurons involved. This network enables mammalian mothers, from rats to elephants, to recognise, invest, attend, feed, bond, teach and provide a secure habitat for their young.

Humans can fight for their god with the intensity and cruelty with which a gorilla will protect her baby

Still, for humans, the ‘apex of evolution’, this neural network, is insufficient to transmit the immense knowledge, linguistic competencies, social cognition, executive functions and mental abstractions we acquired over our lengthy history. Human parenting incorporates several additional higher-order networks controlled from the seat of cognition, the cortex, that enable planning, resonance, and the ability to communicate and share affect; all of this is superimposed on the subcortical brain structures giving immediacy and motivation to caregiving. These include the empathy network (located in the brain’s anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula), enabling parents to feel the infant’s pain and affect in real time; the embodied simulation network (within the brain, traversing the supplementary motor area, inferior parietal lobule, and inferior frontal gyrus), through which parents represent the infant’s motions and emotions in their own brain; the mentalising network (superior temporal sulcus/gyrus, temporo-parietal junction, temporal pole), allowing parents to reflect and give meaning to the infant’s nonverbal signals; and the emotion-regulation network (frontopolar cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex) that helps parents multitask, set longterm goals, and plan their parenting according to the culture at hand.

Such an integrated human caregiving system supports the complex, extensive and multidimensional task of raising human children and preparing them for a life of commitment, industry and social involvement. Because the period after childbirth marks the time of greatest plasticity in the adult brain, human parenting can take on multiple forms, depending on culture and habitat, and still raise a loving, healthy child. Furthermore, thanks to the parsimony principle of evolution, this same flexible system of caregiving also evolved to support other human attachments, such as romantic love and close friendship, in aggregate comprising the human ‘affiliative brain’. Other mammalian species follow the same path; the neuroscientist Larry Young at Emory University in Atlanta and colleagues, studying the monogamous prairie vole, showed that mating and parenting utilise the same neural, cellular and molecular processes, including a molecular ‘fingerprint’ of the attachment target.

The human brain, with its ancient and advanced, automatic and controlled, bottom-up and top-down components, affords a massive expansion of love. It enables humans to extend love well beyond their immediate attachments to pets, to the Earth’s flora and fauna, and – stretching these systems to the limit – to abstract ideas, such as homeland, God or workers of the world. All these abstract forms of love can elicit intense commitment, even sacrifice of one’s life; yet they are all triggered by a 500-million-year-old, nine-amino-acid molecule that surges in the pregnant dam’s hypothalamus.

With such complex neurobiology underlying human love, we fall right back into the human condition. Here is the schism: the extensive brain structures that enable the abstraction of love beyond the here and now – giving meaning to human suffering, inspiring resilience in the face of trauma, and enabling humans to transcend death by acts of kindness – are still connected via multiple ascending and descending projections to the ancient oxytocin-amygdala-dopamine triangle. The ancient and the more-recently evolved parts of the love network cohere into a single, unified system. On the one hand, this lights up an energetic and motivational hearth underneath our love (shall we call it ‘libido’?) that can invigorate, energise and compel our abstract commitments; without it, our life’s road would feel rough and barren.

Yet, on the other hand, the blind, automatic force of the ancient, subcortical triangle does not allow our love to remain abstract, that is, touched by the light of reason, tempered by the perception of multiple perspectives, and seasoned by equanimity and (evolutionary) age. Humans can fight for their god (or their workers-of-the-world god) with the intensity, cruelty and short-sightedness with which a gorilla will protect her baby from predators, whether or not it would cost her life. When it comes to love for one’s tribe, country, religion, code of dress, political system, historical narrative or holy scriptures, a breeze in the leaves becomes a panther, aeons of carefully sculpted mental functions melt and, even within the automatic love triangle, the ‘scare’ overrides the ‘care’. Almost always, the winner is the amygdala, the ever-alert sentinel of encroaching danger, the fount of emotion and fear, all the way to destruction of human spirit and lives.

The third major factor in the neurobiology of bonding is synchrony. Unlike oxytocin and the affiliative brain, synchrony is not a system but a process. Yet it tells much the same story; it is ancient, it evolved to exquisite complexity in Homo sapiens, and its evolutionary roots lurk constantly in the background. Like the Flaming Sword by the Garden of Eden guarding the Tree of Knowledge (the first symbol of multiple perspectives), it can swiftly switch between good and evil.

Synchrony describes the coordinated action among organisms in the service of the group’s survival and resilience. The first scientist to describe the biological underpinnings of synchrony was probably the American entomologist William Morton Wheeler, author of the influential work The Social Insects (1928). Like many children fascinated by a trail of marching ants, Wheeler came to empirically describe the social mechanism that enables these small industrious creatures to carry a grain of wheat much greater than their size. (Indeed, another famed American entomologist, Edward O Wilson, argues that social cohesion made ants the most resilient species among invertebrates, paralleling human conquest of the vertebrate world.) Wheeler suggested that the coordination of leg movements among ants synchronises with the ants’ other neurobiological processes, from neural firing to hormone release, all in sequence and lockstep. In short, he proposed, one ant’s leg movements triggered neural firing in the brain of the next, causing leg movements and then neural firing in a third ant, and so on. Hence, by coordinating across biology and behaviour, the strength of the group is far greater than its individual members would suggest. The same type of synchronous mechanism enables a group of tiny swirling fish to ward off a shark, or a flock of small birds to undertake an amazingly complex, thousand-mile trip toward warmer climates, painting our evening skies with their exquisite dance, autumn after autumn. The wisdom, strength and fortitude that enable small creatures to survive harsh conditions lie within the group, and require total subordination to its rhythms. An injured bird departing from the pack will die in winter.

Humans, by belonging to the class Mammalia and by virtue of their moral reasoning, departed from this coordinated rhythmic submission, but not quite. Throughout human history, this evolutionary heritage has served us well, instilling energy and purpose during work, dance and cultural rituals. For millennia, farmers have harvested via coordinated hand movements, sailors have left shore via a unified lifting of oars, believers have chorused at houses of prayers, and such synchronous activity matched none in its capacity to uplift, instil a sense of purpose, and generate moral elevation. A group in unison creates a far grander and loftier experience than any achieved in solitude or even in a one-on-one encounter. Recent evidence, including studies that film crowds from helicopters and use machine-learning algorithms, shows that humans have ‘herding’ tendencies; they synchronise their walking in large streets, match movements while waiting in long lines, and coordinate running in big marathons. Such synchrony of large crowds, underpinned by the molecule that glues us together, is comforting; it cements our sense of belonging to humankind, a race whose legs are stuck in dirt but with heads that can reach the stars, as so beautifully described by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath (1939).

We are unique in our ability to synchronise via coordination of facial signals without physical touch

Yet coordinated action through the synchrony of the crowd not only unites us but also propels us to derogate, fight and, eventually, kill. It vitalises soldiers in battle and lulls skepticism in hateful political rallies. The ‘together we stand’ in joint union sends a not-so-subtle, ominous message to those who pose real or imaginary danger to our loved ones. We are easily triggered by ‘scare’ to separate ‘us’ from ‘them’, and to go after ‘them’ with zest and zeal. Soldiers receive extensive training for this very goal so that, on any given doomsday, they’ll execute with precision while sublimating thought. It is the group that marches on, not its members. The 20th century has seen countless images of soldiers marching in perfect unison, treading to a variety of gods, goals and goods. Guns on their shoulders and faces undistinguishable, humans have adapted the coordinated leg movements of their ancestor ants while neglecting the ants’ humility, industry, and foresight.

What, then, can differentiate the ‘care’ and the ‘scare’, both evolved from the same ancient mechanisms that helped fish, ants and birds to bond for survival? Here we can be helped by the fact that humans are mammals and, as such, bond within the intimacy of the ‘nursing dyad’.

Also in our favour: the long history of primate evolution that expanded our social brain, lengthened the period of infant dependence, perfected our empathy and, most important, created the uniquely human way of communicating through the face. Indeed, primates, particularly chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas, can show admirable social abilities beyond parental care. For instance, chimpanzees resolve aggressive conflict with group members by consoling behaviour, stimulating oxytocin. Gorillas form coalitions among large groups of unrelated kin in ways that resemble a small human village. But humans are the only species that orients to, and attaches through, the face. Human neonates selectively attend to the human face, humans communicate affectionately in a face-to-face position, and humans are unique in their ability to synchronise via coordination of facial signals without physical touch.

My research group has studied this face-to-face synchrony for years; when partners synchronise their gaze, smile or emotional expression, that spurs coordination of physiological response. For instance, mothers and infants coordinate their heart rhythms during moments of social synchrony, but not during non-synchronous moments; both mother-child pairs and romantic partners show brain-to-brain synchrony of gamma waves during episodes of behavioural coordination but not otherwise. And synchrony of alpha waves in the frontoparietal regions of the brain and gamma waves in temporal regions emerges during ‘support giving’ moments between affiliated partners (romantic couples, close friends) but also among strangers, particularly when the dialogue is empathic. Face-to-face synchrony requires intimacy and intent, invokes reflection and awareness, and obligates significant effort. When parents can validate their infant in a face-to-face exchange during the sensitive period between birth and nine months of age, they orient their child’s brain to the social world and its wonders. When synchrony fails – for instance, when mothers are depressed or when stress is heightened by poverty, war or abuse – the consequences to the social brain can be devastating, and children can develop psychopathology, loneliness, dysregulated conduct or affective disorders that can limit their capacity to engage.

Is there a solution to the human condition? Given that human love is layered over blind forces that react automatically to the slightest sign of danger, is there any chance for redemption, or are we bound to endless cycles of aggression and destruction?

While any random look at human history tells a grim story and gives ample evidence for a hopeless view, I see three types of solutions based on the work of three great thinkers. I call them ‘face’ (the Levinas solution), ‘light’ (the Freud solution), and ‘humour’ (the Kundera solution). Each witnessed fear and cruelty under pressure, and the immense destruction brought by war. Each in his own way tries to free us from the natural way that our brain interprets the world.

The first of these, the ‘Levinas solution’, is based on the work of the 20th-century French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and his recognition of ‘the face’. How can one create an account of the world that describes what ‘is’ (ontology) without resorting to unchanged, abstract, or metaphysical ideas (the work of Parmenides, Plato, and Descartes come to mind)? How can one ground existence in the daily experience of the self-within-the world (as Martin Heidegger does) without placing the self as the cornerstone of all that is knowable? Levinas suggests that the ‘Other’, as presented through the Other’s face, defines unknown territory that cannot be immediately incorporated into the self. That Other, that face, argues Levinas, substantiates the self and, upon seeing the Other’s face, the only possible response is: ‘Here I am,’ fully committed to that person’s wellbeing and safety or, in Levinas’s words: ‘To see a face is already to hear: “thou shalt not kill”.’ Only then can true knowledge – that is, knowledge that can reach the stars, as Levinas says in Totality and Infinity (1961) – be acquired.

I spent countless hours microcoding videos of parent-infant face-to-face interactions, gradually coming to understand that only upon the parent’s attuned face, careful echo and radiant smile can the infant build a bridge to a reality that is often harsh, painful and oblivious. ‘At first was the gaze,’ says the Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos; humans need a loving gaze to start on their life’s road. Looking at your enemy’s face, we hypothesised, makes it impossible to wish him harm.

For the first 500 milliseconds, the adolescents responded equally to others’ pain, whether their ingroup’s or outgroup’s

Several years ago, we put this hypothesis to the test. We developed a dialogue-based intervention for Israelis and Palestinians aged between 16 and 18 years, when group subordination is at its peak. For eight weeks, the adolescents became familiar first with the cultural rituals, then with the immediate habitat, and finally with the family habits and personal preferences, hopes and struggles of each member, creating a common ground where the ‘other’ became familiar and similar. While each session covered a distinct topic (affiliation, conflict resolution, empathy, prejudice), sessions began with coordinated group activities that involved reciting famous poems and holy texts in both languages, face-to-face encounters for a ‘conflict dialogue’ (on a conflict topic of their choice), empathic giving, joint planning or group games involving joint movement and dance. The adolescents were randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. Before and after each intervention they were tested extensively for social behaviour, opinions and attitudes, and hormonal profiles; we also monitored the social brain using magnetoencephalography (MEG).

Our findings on the empathic response were eye-opening. To conduct our study, we exposed our participants to a well-validated set of pictures showing hands and feet in physical pain – examples included a hand burnt by an iron or a foot stuck in a door – which reliably elicit the brain’s empathic response. Before each stimulus, a screen announced the protagonist: ‘This is Danny from Tel Aviv.’ Or ‘This is Ahmed from Kafr Qara.’ Adolescents observed an equal number of stimuli where pain was inflicted on members of their ingroup or outgroup. We found that, for the first 500 milliseconds (representing the brain’s automatic response), the adolescents responded equally to others’ pain, whether their ingroup’s or outgroup’s.

However, after this half-second of grace, the outcomes were different depending on whether our dialogue-based intervention was in play or not. Without the intervention, the brain’s top-down mechanisms began shutting down the neural empathic response to the outgroup, keeping activations only for the ingroup. This later, more cognitive-empathic neural response is critical in order to understand the feelings of others, generate compassion, and form a plan of action. Aborting neural empathy midway doesn’t allow the brain to sustain a fully human response that can activate emotional resonance and practical help.

But adolescents who underwent the dialogue intervention learned to include the Other in their ingroup and display a fully human empathic response to members of the outgroup. The face, as Levinas maintains, indeed compels us, even neurally, to save the Other from pain.

The second solution, from Sigmund Freud, looks to light. From Freud’s immense contribution to human self-understanding, I wish to stress his relentless effort to shed light on our deepest (and ugliest) drives, and his conviction that shining the light of consciousness on those hidden, blind and automatic motivations can rescue us from our cruel and pleasure-seeking nature. What a radical position to suggest that sheer awareness can combat the push-and-pull of the subconscious! While Freud emphasised that the road to light is long and arduous, involves walking in the thickets of defences and contradictions, and requires stubbornness and severity, he was the first to suggest that the ‘way out’ of the human condition is through dialogue. Although I have a hard time accepting his neglect of the face for the couch in this important human dialogue, Freud’s model was the first to offer a carefully crafted route to healing through knowledge, toiled by two.

Freud’s quest for light echoes the ancient Greek ‘know thyself’. But I am also reminded of an old Talmudic verse, probably dated from the same era as Socrates: ‘If you meet the devil, shine on it the light of knowledge. If it is stone, it evaporates; if it is metal, annihilates.’ What a triumph to the human spirit is the belief that the hardiness, nastiness and ‘stone-ness’ of our nature can be overcome by the ‘light of knowledge’.

My third solution, humour, is inspired by the novelist Milan Kundera, a victim of the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, exiled to France. Kundera summons the insights on the human condition through the history of the novel, laid out in The Art of the Novel (1986) and Testaments Betrayed (1993). The 400-year journey of the novel, he suggests, is to break the overarching single narrative we form of reality, the one inherited from parents, corroborated by neighbours, tended by culture, cemented by religion, and imposed by totalitarian regimes, which, without a radical shake, would stand to testify for truth. Our brain typically creates a single percept that discards all information not befitting our ‘story’, but the novel upsets this singularity.

Look at someone’s face with compassion; climb the Tree of Knowledge; and practise a good laugh

And it does so via humour. While truth is dead serious, humour is suggestive, nonsensical, unnerving, contradictory, and functions at multiple nonadjacent levels simultaneously. Humour weaves together a kaleidoscope of images that not only are not neighbours, but have never even resided in the same continent.

Humour is a fine panacea to the pompous ‘together we stand’. Practised to perfection, it knocks precisely those marching soldiers off their feet (letting our ants keep their industrious sisterhood). How easy can it be to march to a humorous idea, fight for an ‘either-or’ programme, or conquer cities in the name of a smiling god? (Kundera began his acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize for Literature in 1985 with the old idiom: ‘Man thinks, God laughs.’)

Here’s to three solutions: look at someone’s face with compassion and care; climb the Tree of Knowledge and cherish its multiple branches; and practise a good laugh. These could help tune the environment-dependent, behaviour-based systems comprising the neurobiology of affiliation to a life of lasting love.

While the neuroscientific programme of the human brain is couched in an evolutionary framework, the grand theory of the biological sciences has its limits as a singular window into the human condition. The psychiatrist and neurobiologist Myron Hofer at Columbia University in New York spent his career describing the biological provisions embedded in the mother’s body. He reminds us that, when it comes to human development, an evolutionary viewpoint must be complemented by insights from other fields of knowledge: the humanities, the arts, and clinical wisdom. Hofer maintains that, while evolution is impartial to the individual child, the individual is precisely what matters for human life. The goal of a human programme set to understand how early environments meet or fail the needs of their infants is to enable the individual to benefit from the fullness of the human experience afforded by modern science – long time to maturity, planned parenthood, freedom from infectious disease, literacy and a manageable stress response. Human research, therefore, must translate into brief and widely deliverable interventions that maintain the deepest respect for the individual’s cultural heritage, personal meaning, and life journey.

‘It is time the stone made an effort to flower,’ writes Paul Celan in his poem ‘Corona’: ‘Shine on it the light of knowledge – if it is stone, it evaporates.’