Photo by Hermes Rivera/Unsplash

When I was training as a clinical psychologist, I had a rotation in a low-cost psychotherapy clinic. Among the first people I met was a young man who believed that he might be responsible for harm coming to his family if he didn’t engage in time-consuming rituals, including arranging his shoes very particularly for up to half an hour. The logic motivating this man’s behaviour was notably rather magical and unrealistic, appealing to notions of spirit possession and evil, which were culturally alien to his family. My supervisor, a sensitive and empathic clinician, who believed that most issues could be addressed by attentive listening and interpretation, tended to have a single diagnostic concern. The central question for him was whether the person was experiencing anxiety or manifesting the early symptoms of a psychosis. The latter ought to receive a more thorough assessment and more support than our clinic could offer.

Because of the magical quality to this person’s reasoning, my supervisor decided that this might be an early sign of psychosis. He instructed me to refer the man to a new research clinic near my training site, which specialised in treating and researching the ‘at risk’ state for psychosis.

Of course, sensible and cautious though this seemed to me, it entailed telling this young man that he could not be seen by us for talking therapy. Instead, he should go to a clinic that specialised in something serious and frightening-sounding. When I broke the news, he was devastated. He left our clinic, and I later learned that he never followed up with the referral.

What I failed to appreciate at the time – and what some remedial reading later painfully revealed to me – was that, rather than being an early manifestation of psychosis, this man’s presentation was more likely a case of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), a common condition in which people develop obsessive thoughts and feel compelled to engage in actions to prevent feared harms. If I’d had the diagnostic knowledge and confidence to assert this to my supervisor during the initial consultation, the man I met would likely have received help, rather than being referred to an inappropriate clinic that led to him falling through the cracks.

Yet, a popular and longstanding wave of thought in psychology and psychotherapy is that diagnosis is not relevant for practitioners in those fields, and should be left to psychiatrists, if at all. This is not a fringe view, it has been perennially present in clinical psychology since at least the 1960s, when the iconoclastic psychiatrists Thomas Szasz and R D Laing presented a dual challenge to their profession.

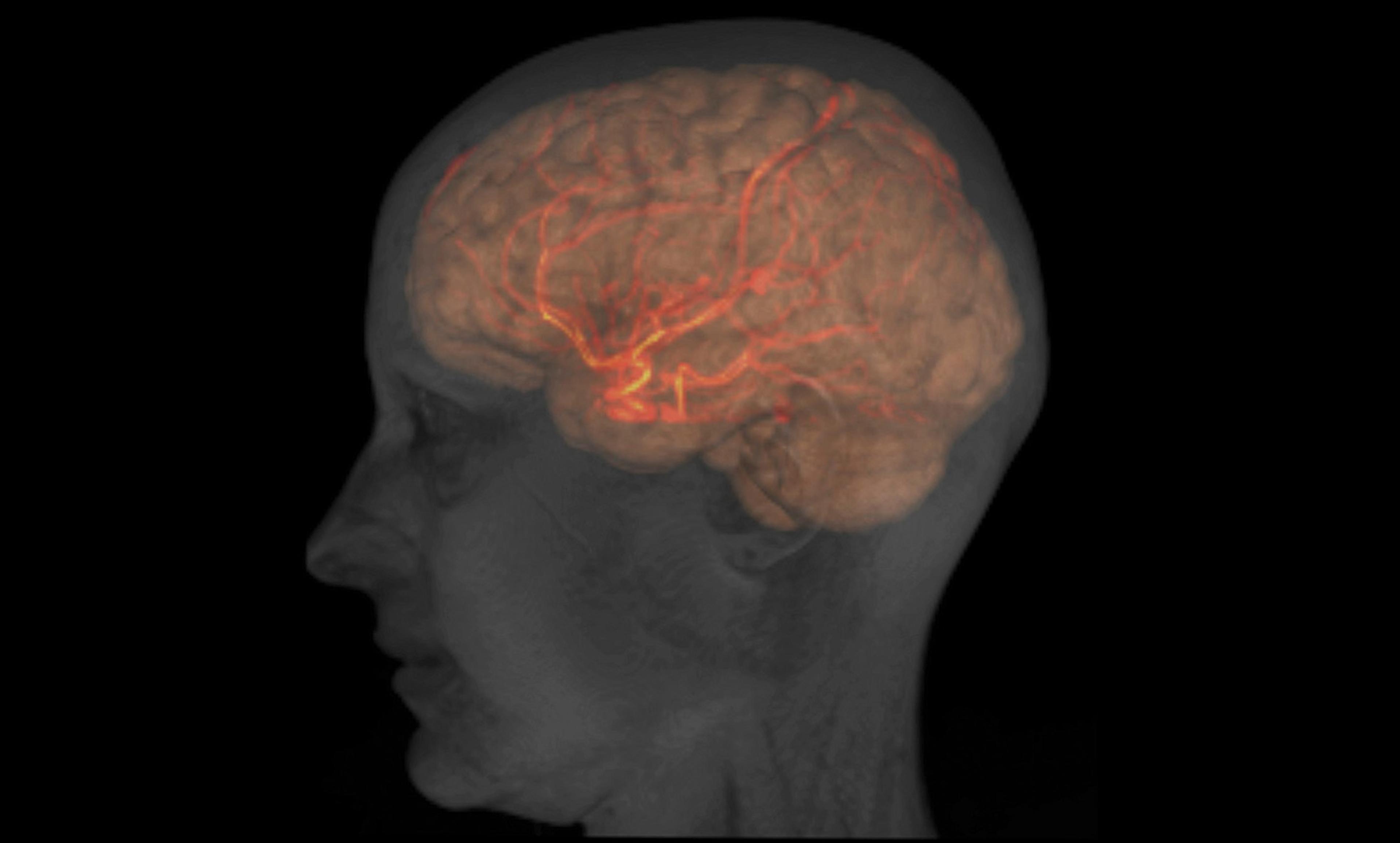

Szasz, a Hungarian émigré to the United States, argued that mental illness is a ‘myth’, rooted in a misuse of language. Neurological diseases are real, Szasz suggested, because they can be confirmed by a postmortem examination of the brain. In contrast, he argued that psychiatric ‘illness’ has no such neurological basis, and is just a medicalised way of talking about problems in life that could be solved by taking responsibility for yourself and your actions.

Meanwhile, Laing, a Scot who trained at the Tavistock Institute in London, argued in The Divided Self (1960) that psychosis is a psychic response to an increasingly alienated ‘false self’ obscuring the true emotional core of an individual. He held that so-called ‘symptoms’ (hearing voices, believing unusual things) were actually attempts at recovery in the face of this alienation.

These ideas resonated and had significant influence over psychiatric thinking throughout the 1960s. They contributed to diagnostic approaches to mental health – the idea that there are illnesses called schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression – becoming decidedly unfashionable. Indeed Szasz’s and Laing’s critiques became so popular that already by the early 1970s, the influential US clinical psychologist Paul Meehl grumbled in his 1973 paper ‘Why I Do Not Attend Case Conferences’ about an ‘antinosological’ (ie, antidiagnostic) bias taking hold in his profession.

Recently, the animus against psychiatric diagnosis has become more formal and scientifically argued. The British Psychological Society’s Division of Clinical Psychology (DCP) – one of the official bodies representing the profession – published two documents in 2013 and 2015 articulating the difficulties with diagnosis, and promoting instead the value of individualised ‘formulations’. While it is clear that the DCP’s position on diagnosis is not universally held by practitioners in the UK, British psychologists are around half as likely to report regular use of a diagnostic classificatory system as their colleagues in some other countries (for example, fewer than 35 per cent of psychologists in the UK say that they use diagnosis regularly, compared with more than 70 per cent of psychologists in the US, Germany and South Africa). This likely reflects a UK professional culture steeped in suspicion of diagnostic thinking.

The suspicion is not unwarranted. One of the most interesting recent critiques of diagnosis has come from the Belgian psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist Stijn Vanheule. He invoked the philosophy of language to argue that diagnosis necessarily draws our attention to the shared meanings conjured by diagnostic language, rather than to the individual meanings inherent to people’s experiences. Thus, for example, when I say ‘schizophrenia’, I focus attention on a generalised, clinical definition that exists in a book, rather than on the individual, personal significance of hearing voices or believing unusual things. For psychotherapists, Vanheule argued, the former is irrelevant, the latter vital.

These arguments are valuable, and they are correct in important ways. Their conclusions are a significant part of what inspired me to get into clinical psychology in the first place. Reading Laing as a teenager, I thrilled to the challenge he presented: to understand people as they endure the most extreme and bewildering psychic states; to try to find coherence even where it seems to be absent. This impulse is essential. Patience and careful listening can reveal that people are capable of engaging in communication more often than we tend to give them credit for. But my clinical training has shown me that, despite the importance of understanding people in an individualised way, having a knowledge of diagnostic categories is also essential.

To return to the example above, my supervisor and I were ignorant of valuable diagnostic information; we were ignorant of the ways that clinicians can distinguish magical obsessions from the early hints of delusion. We were ignorant of the fact that even quite magical ideas are well within the range of the former without shading into the latter. We were ignorant of how easy it would have been to provide effective help without raising the prospect of a terrifying psychosis down the pipeline. Our ignorance cost someone dearly.

Diagnosis is often vital for ensuring good care. Apart from the importance of ruling out organic causes for apparently straightforward instances of depression and anxiety (which can be symptomatic of a surprising range of endocrine, infectious and neurological diseases), linking psychological distress into a broader framework also helps clinicians make sense of the people they are trying to help. Certain forms of substance misuse could represent attempts at self-medication for highly treatable disorders of mood or attention, for instance. Correct identification of trauma symptoms can avert diagnosis of a psychotic illness. Proper diagnosis of depression in later life can frequently account for changes in memory and attention that might otherwise be mistaken for dementia, as unfortunately often happens. Diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder can prevent people being inappropriately treated for personality disorders.

Psychology’s antinosological tendency encourages a belief that diagnostic thinking is somehow inherently unkind; that in thinking about categories you are always only ‘labelling’ people, and that this is an inhumane thing to do.

Conversely, it also encourages a belief that all you really need in mental healthcare is sympathy, rapport and interpretative heroics. This appeals to some of the questionable impulses of professionals: to our desire to see ourselves as people uniquely able to understand others, and to our ordinary human laziness. Who would want to engage in learning about taxonomy if to do so is both unkind and unnecessary?

Understanding people is a multifaceted enterprise. We all manifest a splendid idiosyncrasy, living out lives that could never be copied or repeated, so it makes sense to consider one another in the light of this uniqueness. But we also bear resemblances to one another. Important though it is to be seen in all your individuality, it is also helpful to know when your problems have precedent.

Psychiatric diagnoses are imperfect, sketchy theories about how people’s minds can give them trouble. We know that they are largely less precise and valid than is popularly understood, but this does not render them totally uninformative. We have learned snippets of useful information by considering psychological problems in terms of categories: the effectiveness, or not, of treatments for particular groups of people; the elevated risk of suicide among others. Many symptoms can seem to ‘make sense’ in the context of a person’s life, but we know that humans are sense-making machines, so we need to be vigilant against ‘making sense’ where it is only illusory. The great intellectual challenge of clinical psychology is to integrate knowledge about reasons and people with knowledge about causes and mechanisms. We should avoid relying solely on diagnostic information, but we shouldn’t discard it altogether.