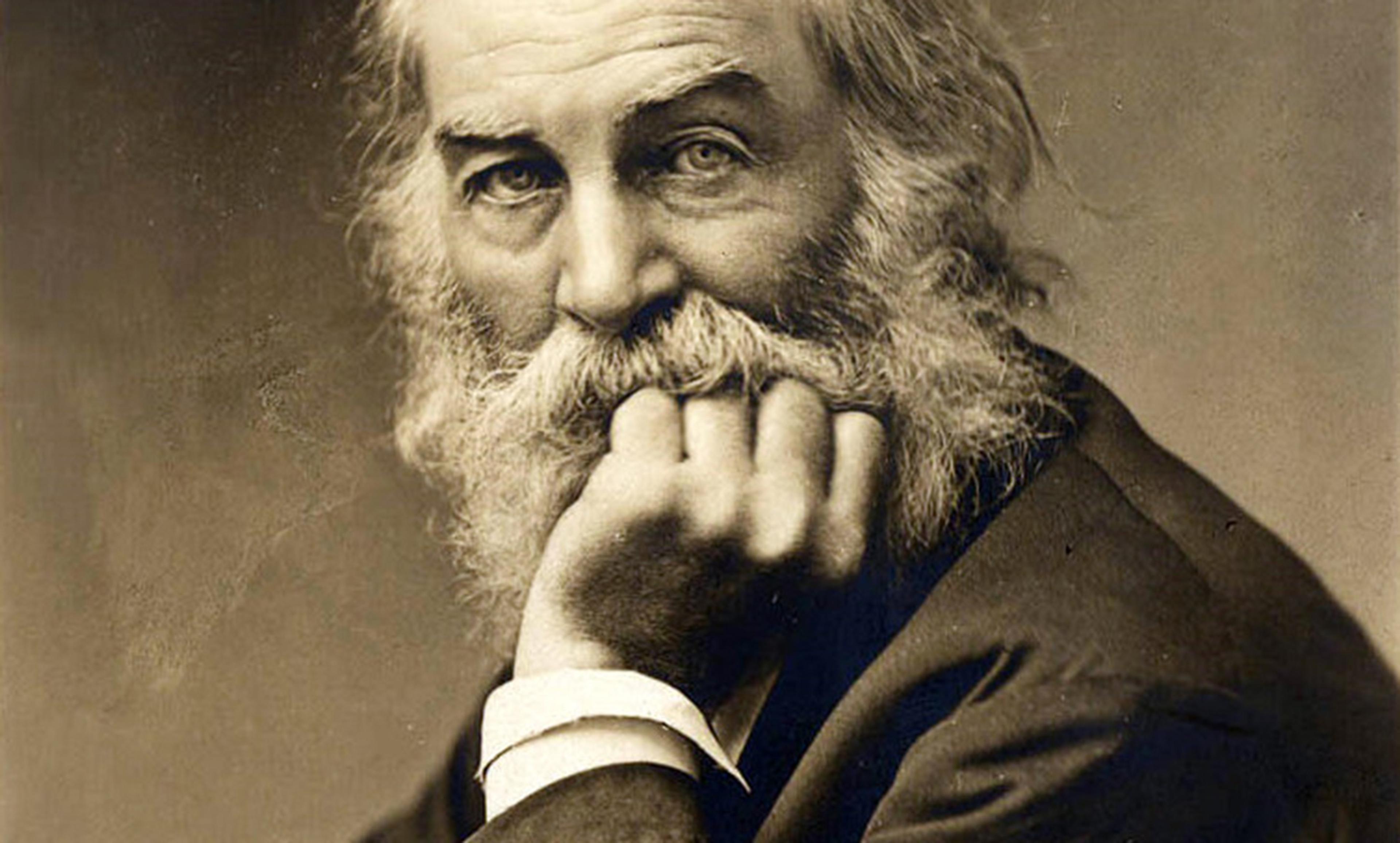

Walt Whitman; the face of masculine vulnerability and pride. Courtesy Wikimedia

In the West, for many centuries, shaving has identified a good man properly oriented to a higher order, whether divine or political. Defying this regulation meant being ostracised. But on occasion, a general reorganisation of masculine norms has interrupted the shaving-respectability regime.

Alexander the Great established shaving as the ideal in Greco-Roman civilisation when he imitated classical depictions of eternally youthful gods. Though there was a brief resurgence of beards inspired by Roman emperors, the Alexandrian style held well beyond the Empire’s fall. In medieval centuries, men of the Church made the tonsured head and shaved face marks of holiness and goodness, going so far as to inscribe these practices into canon law. Laymen followed suit, cutting back their beards to be worthy in the sight of God and man. After Renaissance men embraced hairy nature over holy shaving, beards were again curtailed by new codes of gentility enforced by royal courts, which had effectively replaced the Church as guardians of the moral order.

The breakdown of the clean-shaven order in the middle of the 19th century offers a valuable comparison with our own day. At that time, men on both sides of the Atlantic had new reasons to boast, but to also feel uneasy, about their status as men. Revolutions in Europe and the United States declared the rights of man, investing power in a sex, rather than a class. This gave men reason to assert their manhood with pride and, as one might expect, the most radical republicans and socialists were also the most enthusiastically bearded. By the middle of the century, the decline of radicalism uncoupled the link between radicalism and facial hair, allowing men of all classes and persuasions to assert their manly pride. No one expressed this new spirit more vibrantly than Walt Whitman, whose 1855 hymn to physical vitality, ‘Song of Myself’, declared ‘Washes and razors for foofoos … for me freckles and a bristling beard.’ Copies of the poem were sold with a full-length drawing of the poet, to show him true to his word.

As Whitman suggested, beards were liberating and empowering, and were accordingly embraced by men of every rank, from patricians to day labourers. Behind this pride, however, there was an undercurrent of worry. Even as the male sex was granted higher political status, masculine dominance was challenged by nascent feminism in both the private and public spheres. This challenge reinforced men’s determination to abandon razors. Those who championed beards praised them for establishing an unimpeachable physical contrast between men and women that demonstrates male superiority. The authors of a manifesto for facial hair, written in 1853, argued that nature assigned to women ‘attributes of grace heightened by physical weakness’, and to man ‘attributes of dignity and strength’. Men’s work, they insisted, is outdoors in wind and weather, and nature provides them suitable protection. Women’s work is of a different order.

The problem with this line of argument was that, even in the 1850s, the London journalists who penned these words were hardly outdoorsmen in need of beards to guard them from the tempests of Fleet Street. Yet this was precisely the appeal of the beard to urban men both then and now. Disconnection from nature and the increasing irrelevance of physical strength, along with the gradual rise of women in public life, threatened to destabilise common understandings of manliness at the very moment when manhood had achieved new political status. Facial hair served as a tangible symbol of gender difference that was in danger of becoming intangible. It is fair to say that a beard made the man.

Like the 1850s, today there is a renewed gender uncertainty that erupts in peaceful times when older constructions of manliness lose relevance. Then as now, war was limited and distant, and not available as a universal definition of masculine purpose. In the 1850s, the athletic ideal was in its infancy. In our time, sports have become so pervasive that they have begun to lose their specific association with masculinity. Even more than in the 1850s, it has proven difficult to police the boundary between the masculine and the feminine. Politics, business, sports, war, even masculinity itself, are no longer unchallenged male preserves. People born female are asserting their claim to be men, whether altered by surgery or not. Still others are declaring they have no sex or gender at all. Some men have navigated this fluid environment with remarkable aplomb. David Beckham openly embraces his ‘feminine’, fashion-conscious side, while at the same time always sporting a masculinising beard. With facial hair, he can have an effective physical presentation of contemporary manliness.

As they did in the 1850s, men of every region, race, class and political persuasion are again growing beards to declare the reality of masculinity, as well as their own masculine identity. While there is diminished confidence that nature has conferred upon men any particular quality or status, it might be enough for most to simply establish that they are indeed men, whatever that might entail. Like his 19th-century forebears, a bearded man today demonstrates both masculine vulnerability and pride. His status might be contested, but he puts on a brave face.