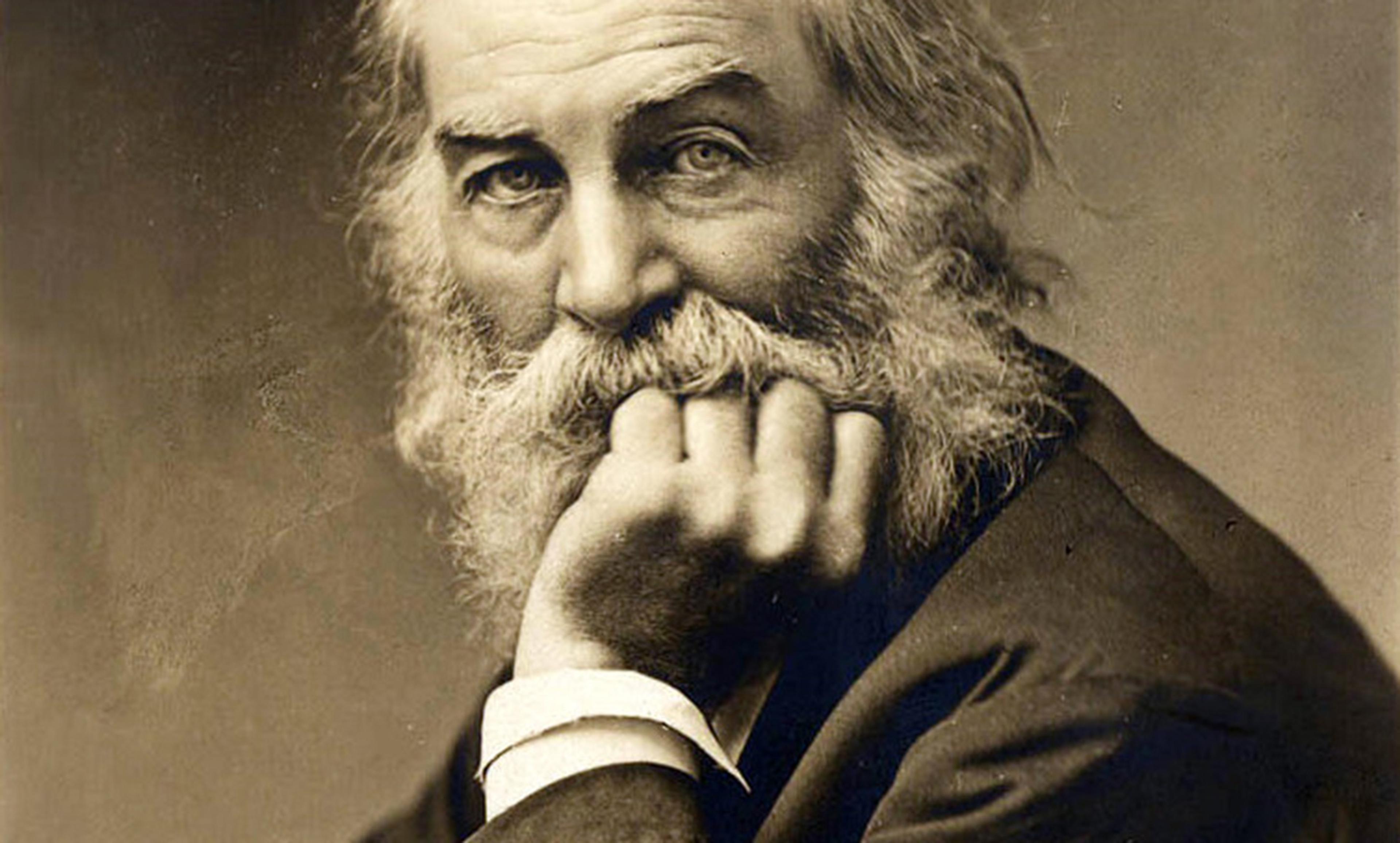

From The Annals of Horsemanship (1791) by Geoffrey Gambado, Esq. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

For much of human history, horses have been our travelling companions, our weapons of war, our industrial machines, our shoe leather, and our dog food. They have influenced human society around the world, including what it meant to be a man during the 17th and 18th centuries. At that time, Britain was known for the English Civil Wars and the rise of the British Empire. It was also an age in which, for many men, horses were indivisible from their masculinity, their ability to govern successfully and their personal identity. While the practice of horsemanship changes over the period, equestrian skill and the ability to present oneself as a unified being with a mount was a central component, for many, of what it meant to be a man.

When people viewed horsemen and came to interpret the masculinity on display, they tended to view the horse and rider as one unit. During the 17th and 18th centuries, those deemed worthy of the appellation ‘horseman’ were of the upper classes, and had developed a close partnership with their horses. As Richard Berenger, Gentleman of the Horse to King George III, argued in 1771: ‘The Centaur is the symbol of horsemanship, and explains its meaning as soon as it is beheld.’ For Berenger, because of the close communication between rider and horse that develops over time, a rider and his horse were ‘almost in a literal sense … one creature’. Becoming such a centaur required a lifetime of effort, practice, patience, rational control of the self, and in many cases natural ability by both man and horse. To become a centaur meant, for men of the upper classes and for those who wished to join their social ranks, perfection in classical dressage (known as the manège), including clear and nuanced communication between horse and human at all times. It meant that they performed together, and appeared as one being. These centaurs were the ones whom the public and fellow riders understood as manly, ideal figures of masculine prowess, secure in their status as masters of the equestrian arts.

However, working with a horse and striving towards centaur status did not always go according to plan. Henry William Bunbury, equerry to the Duke of York, illustrated the connection between horses and men. Dubbed ‘the Raphael of caricaturists’, and the artist responsible for one of the first comic strips, Bunbury spent his life capturing the follies and fools of his age, especially false horsemen. He published two books of caricature dedicated to the subject. Intended as mock-manuals of horsemanship, Bunbury’s An Academy for Grown Horsemen (1787) and his subsequent Annals of Horsemanship (1791) won rave reviews but were published pseudonymously under the name ‘Geoffrey Gambado, Esq’. A person of dubious equestrian connections, a follower of radical politics, and a man of questionable masculinity, Gambado is a prime example of how important skill in horsemanship was to 18th-century men.

Gambado was described as the son of a Devonshire tailor. This lineage was a direct reference to the stereotype of failed horsemanship and masculinity popular throughout the 18th century. Tailors were indispensable to that era’s fascination with fashion, but a tailor’s link to clothing and to conspicuous consumption, immediately made his masculinity suspect. Popular opinion routinely lamented that tailors had more interest in the shape of a gentleman’s lapel or a lady’s stays than in being useful to the nation. And tailors certainly didn’t spend their time learning to ride. As the popular circus act ‘The Taylor Riding to Brentford’, which played at Astley’s Amphitheatre in London well into the 19th century, made clear, tailors were ‘equally singular in their dress and bad horsemanship’. Famously effeminate, selfish and civically or militarily useless, tailors were seen as a leading cause of social corruption in the period. While in theory able to pass criticism, in the streets – as Bunbury and the circus made clear – their poor handling of their horses dramatised their emasculation.

Popular 18th-century wisdom held that horses were powerful agents of truth. While near them or on their backs, nothing their riders did could be hidden from onlookers. In the circus, this equine agency was expressed through the acting abilities of Formidable Jack, a horse who had ‘been trained so as to withstand every horseman dressed in the garb of a tailor’. Formidable Jack would chase the tailor, playing the role of failed masculinity and rampant effeminacy, by biting and kicking at him, and doing everything in his power to destroy the respectability and rational governing abilities necessary to period masculinity. These actions contrasted with his response when faced with a true horseman, of masculine virtues, before whom Formidable Jack proved respectful, ‘gentle and governable’. From chivalry and honour in the 17th century, to politeness and sentiment during the 18th century, horsemanship dramatised a man’s worth. A man properly educated in horsemanship knew how to communicate with and train his mount; the behaviour of his horse rewarded his efforts.

Gambado was not rewarded for his equestrian efforts – he was said to have died en route to Venice, clutching his saddle as an ineffective flotation device. As a tailor, he was dangerous to society, and as a tailor pretending to be a horseman, he was potentially disastrous. Britons of the 17th and 18th centuries understood horsemanship, or the governing of horse and human, as the embodiment of proper masculinity, and by extension, the embodiment of the man’s ability to govern the world around him. Horsemanship was political, and in this understanding the man represented the ruling monarchy (the father), and the horse the nation (the rest of his household). How well the two interacted, and how well the rider governed the horse as centaur, illustrated the man’s ability to be the patriarch of the house and the nation. Horses and riders were essential to the kingdom because they were the means of ensuring a properly functioning civil society. With emasculated figures such as Gambado, however, the continued prosperity of Britain was in doubt. Tailors could destroy everything because of their effeminate lack of equestrian skill.

For many men of the early modern period, regardless of whether their efforts at achieving centaur status went according to plan, horses were essential partners to their gendered identities. Masculinity was not an individual pursuit; instead, horsemen believed that horses and humans needed to work together to get it right.