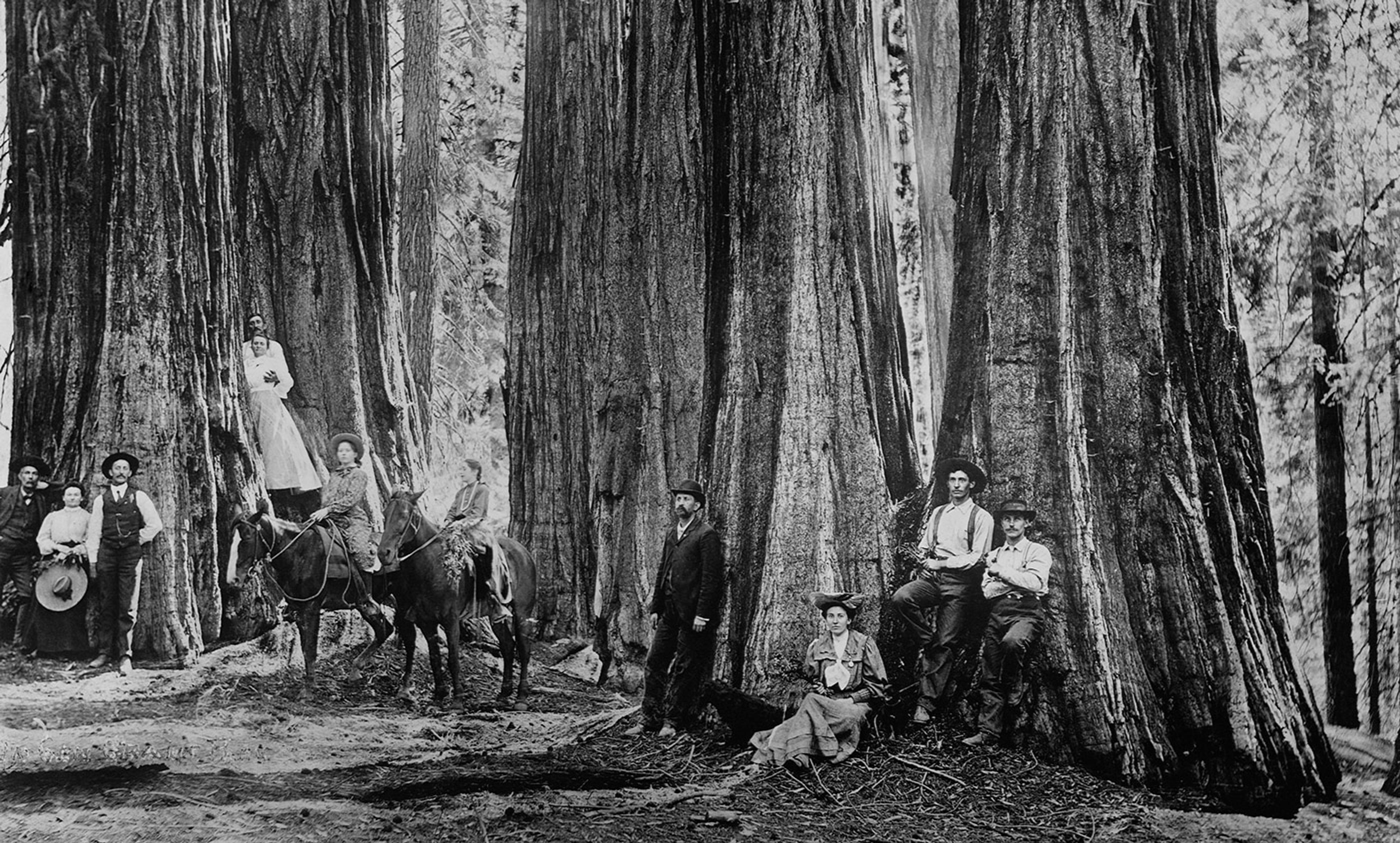

Rob Kerr/AFP/Getty

One big drawback to the role of the heroic American frontiersman is that you seldom get to bask in the glory you earn. If you do the job right – battling nature, taming the land, boldly going wherever Manifest Destiny dictates – you die of exposure or sepsis somewhere west of the Rockies, and no one ever knows what kind of critters ate your body.

This is the lesson currently being taught at Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge: the grand western landscape might make a superb backdrop for heroism, but it doesn’t pair well, logistically speaking, with the media attention today’s would-be heroes need. You want to protect the Constitution by bunking in a commandeered gift shop in seven-degree weather? Bully for you! Unfortunately, not many people want to stand around in seven-degree weather watching you do that.

For one thing, it’s expensive. You need a lot of cold-weather gear; plus, no one delivers pizza to a wildlife refuge, so you have to bring your own food. It all adds up. Consider that it cost $135 million to make this season’s blockbuster wilderness-porn flick The Revenant, largely due to the difficulty of dragging a film crew into the depths of British Columbia during wintertime. That’s what it takes if you want your triumphant tale of survival and vengeance to find an audience. It doesn’t matter that you can wrestle a bear, eat raw bison liver, and fall off a cliff every bit as convincingly as Leonardo DiCaprio; if no one catches it on camera, your sacrifice is of minimal benefit to your cause.

Which is probably why burying oneself in the backwoods has traditionally been a way for malcontents to disappear, not to start national movements. The frontier was early America’s solution to the problem of active men with sub-par social skills (what in 1805 the French statesman Talleyrand called ‘cette multitude de malades politiques’). You don’t need social skills or a knack for negotiation to fight a bear. You taste the same either way, and that’s all the bear cares about.

If you want to impress anyone other than the bear, however, running off to the wilderness is a move in several wrong directions. It not only separates you geographically from your intended audience, it distances you symbolically from the people you profess to care about. Moreover, if you occupy a public wild space in order to claim a greater right to it than the federal government’s, you’re also running counter to the democratic ideals of the nation you claim to love.

Lacking a film crew, the armed occupiers in Oregon protesting the imprisonment of two ranchers for arson have been posting videos on social media. These homemade productions favour exposition over action; the men in them talk at great length about their beliefs, their willingness to die, their love of family – all the traits heroes are supposed to be imbued with, they solemnly swear they possess. However, what comes across most strongly in this roll call of admirable qualities is how badly these men crave admiration. Likewise, their repeated calls for unity, for people to ‘come together’ and ‘take a stand’, ‘shoulder to shoulder’, serve primarily to remind the viewer that stable, productive unity among humans – otherwise known as community – requires tolerance and compromise, not guns and obstinacy. Rugged individualism can help you survive in a forest, but when you live with other people, it mostly leads to fistfights. In fact, when heavily armed members of the Pacific Patriot Network answered Bundy’s pleas and showed up at Malheur, they were promptly sent away. Extolling shared sacrifice is one thing; sharing the limelight is something else entirely.

Maybe this basic ignorance of how civilisation works is inevitable if you grew up, like the leader of the Oregon protest, Ammon Bundy, on a Nevada ranch with a delusional racist for a father. Maybe a childhood like that makes you crave a sort of acceptance you can never find, because functional relationships are so alien to you. There’s a telling moment in another of the militiamen Jon Ritzheimer’s videos when he accuses the Oregon ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond of ‘succumbing to the oppression and the tyranny’ merely because they agreed to serve the prison sentences they earned after being duly convicted by a jury of their peers. The fact that 12 members of the Hammonds’ own community judged their actions punishable is irrelevant to Ritzheimer and Bundy. In their minds, the Constitution gives each of us the right to kill federal employees whenever we disagree with the outcome of due process. What a lucky thing for our nation that the people of Ferguson and Baltimore and Chicago, who staged peaceful protests at police conduct over the past couple of years, believe otherwise.

There’s an undercurrent of anxiety in these videos from Ritzheimer and Bundy. You can detect it in the repetition, the long pauses, the rhetoric that substitutes fervency for logic. It’s as if these men are worried that they might stride courageously off into the wilderness… and never be missed by the rest of us. And they’re right to worry. Most reasonable people don’t want to follow someone who stands on a frozen rock in the middle of nowhere, waving a gun and yelling about tyranny. Most of us prefer it when people like that stay far away. We’re happy to let the wilderness absorb their fury and disappointment.

A central challenge that democracy in the US currently faces is that we have a sizeable surplus of such people, and we don’t know what to do with them. We can no longer rely on bears and hypothermia to solve the problem of civic ineptitude; we’re producing the malades politiques faster than nature can clear them out. So our would-be revolutionaries wander the margins, riding the trail from one lonely outpost of patriotic resistance to another, toting their weapons and nursing their grudges.

Can a democracy survive without a wilderness to swallow its malcontents? Talleyrand, a political genius who survived the French Revolution and the reign of Napoleon, didn’t think so. Let’s hope he was wrong.