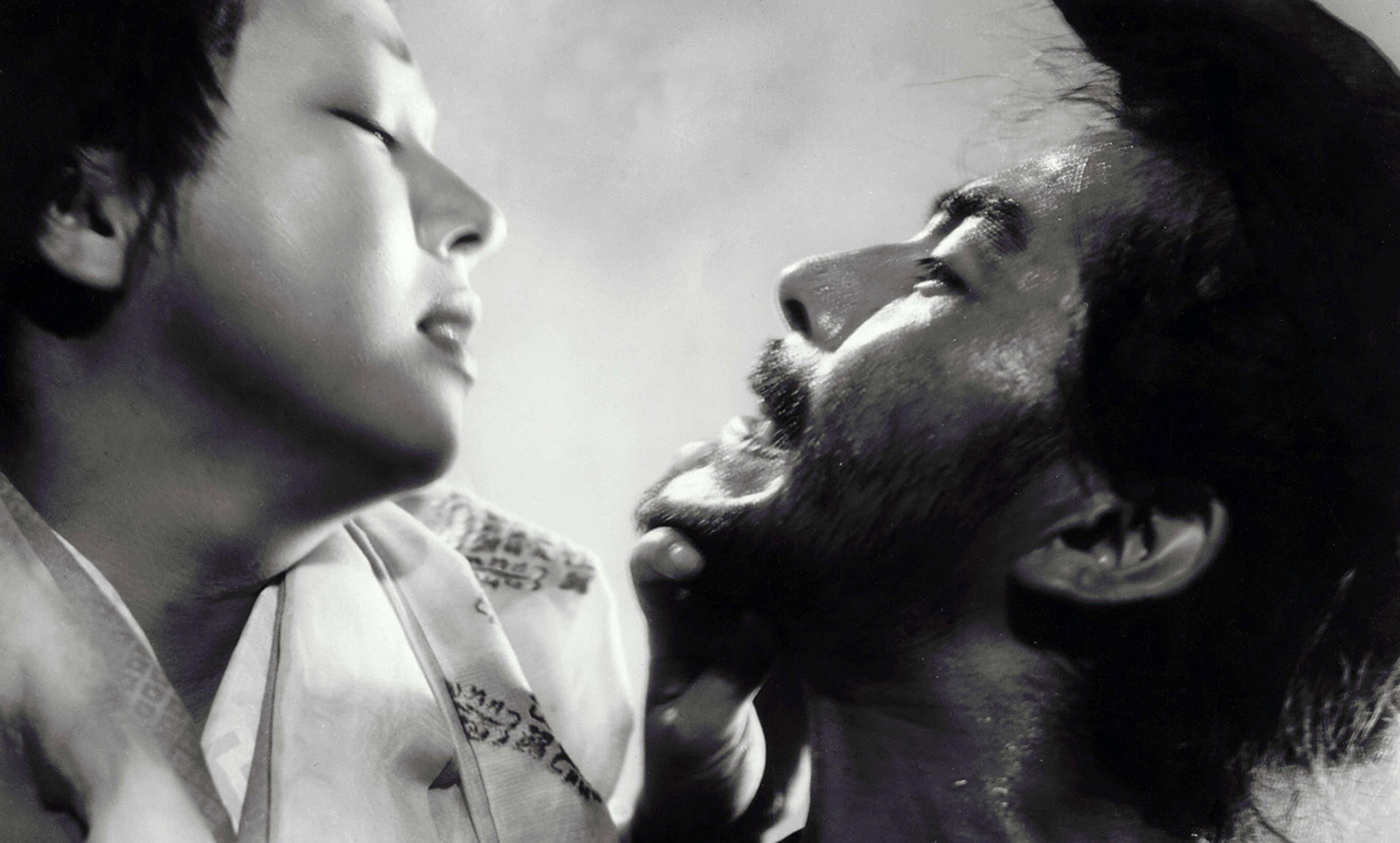

Posters advertising screenings at the 12th Pyongyang International Film Festival in Pyongyang, North Korea. Photo by Ian Timberlake/AFP/Getty

The 2,000-seat auditorium was packed. Well-dressed women rushed to their seats; the clacking of their heels reverberated around the hall. Men, scrambling in front of different stalls to buy beer and chocolates, became rowdier as the start of the show drew closer. Families were still streaming in when the screen lit up. The only empty space was on the floor, and it was soon occupied. The scene resembled a regular Sunday evening in many cinemas around the world – particularly the ones from my childhood in India.

Until, that is, I turned to the back of the room. ‘Let us model the whole Party and all society on Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism!’ had been emblazoned in red across the back wall. I was in North Korea, and reminded that – in form and function – a cinema hall in the hermit kingdom is unlike one anywhere else.

I travelled to North Korea in September last year to study the place of leisure in its society. I attended the state’s showpiece film festival in Pyongyang, and visited a pizzeria, a water park and a pub, as well as other destinations in and around the capital. In many societies, lights going out in an auditorium induces a sense of anonymity and spontaneity. Sure enough, the hours I spent in a North Korean cinema provided my most natural encounters with locals; the gasps and guffaws I heard were undeniably real.

But the performance wasn’t limited to the screen. At one point, my minder leaned over into my seat and whispered: ‘I love patriotic cinema like this.’ I was reminded of eyewitness accounts from when Kim Il-sung died in 1994; mourning in the streets turned into a forced spectacle as citizens were afraid they would be informed upon and punished if they didn’t cry loudly or long enough.

The word ‘leisure’ can be traced back to the Latin term licēre, meaning ‘to be permitted’, and its French variant loisir, ‘to enjoy oneself’. It carries connotations of liberty, latitude, the suspension of one’s duties, a freedom from necessity. But are any traces of this freedom available to a person living in North Korea, under a regime that demands absolute loyalty to the nation?

Ordinary North Koreans have few opportunities to collaborate with their compatriots in the name of art or relaxation. Non-official meetings of more than four people can be deemed illegal, so public space is tightly controlled. Instead, people must partake in leisure activities that are conceived, produced, and distributed by the state. But this set-up makes a mockery of escapism as we know it. After all, you can hardly disappear down a rabbit hole when you’re being led hand-held along a narrow path.

In most democracies, leisure spaces are not just for escapism and consumerism but also assembly and critique. Award winners and presenters at the Golden Globes, Oscars and British Academy Film Awards used the podium to deliver stinging indictments of government policy. The opening ceremony of the 2016 Pyongyang International Film Festival, by contrast, featured a musical performance called ‘Oh, I Love My Motherland!’ For a person living in North Korea, leisure can be an extension of, rather than relief from or resistance to, the burdens of being a citizen.

Regardless of the kind of leisure venue one frequents, the overarching cultural narrative in North Korea comes from the state. The beneficence of the ruler – from Great Leader Kim Il-sung to Dear Leader Kim Jong-il to Respected Leader Kim Jong-un – is emphasised at every possible opportunity. When you walk in through the gates at Munsu Water Park, you are greeted by a statue of Kim Jong-il in a suit, enjoying himself at the beach. Your guide, your minder, or both, will not fail to remind you that Kim Jong-un visited the park multiple times while it was under construction. ‘The Grand Marshal insisted the park be managed for the people’s convenience,’ my guide told me, beaming with awe.

It’s of immense importance to the regime that there be public displays of pleasure. The pages of Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of the Workers’ Party of Korea, are littered with photographs of Kim Jong-un laughing along with children or examining a gleaming new piece of infrastructure. These accounts of development and happiness are what Kim Jong-un’s regime constructs its national narrative from. In a country where a citizen can visit another district only by obtaining a permit – a process that takes months without bribery – the presentation of what life is like far away is a potent message of progress.

The disparity between public and private lives is so stark in North Korea that leisure spaces must be separated from leisure activities. The same person attending the premiere of a film about the virtues of a socialist lifestyle is more likely than ever to head home and watch a South Korean movie bought on the grey market, with doors closed and curtains drawn – even though possessing unapproved foreign media is a crime.

A few years earlier, this person would have purchased the illegal title on DVD. Putting it into a player would have presented an immense risk. In the case of an electricity outage – a common occurrence – the disc would be jammed inside; law-enforcement officials are known to have barged into houses to check players for their contents. But today, with the proliferation of USB sticks and portable players with inbuilt batteries, this person can indulge with a level of confidence, even brazenness, that has come to characterise the most subversive strand of leisure activity in North Korea.

The South Korean movies most popular in the North tend to cluster at the more fanciful and escapist end of the market. However, to North Koreans, who are force-fed an incessant diet of ever more unreal plot lines, in which the loyal labourer is rewarded for his hard work and patriotism, it’s the strange plausibility of these contraband films that makes them so alluring. The bad guys win on some occasions. State actors don’t always do the right thing. In North Korea, then, escapism is one of the only things that offers a dose of reality.

The fieldwork for this essay was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.