DonkeyHotey/Flickr

Each time I learn of another terrorist who spent time in prison, I’m taken back to my own prison time. In 1994, I was caught smuggling hashish into South Korea and spent three and a half years imprisoned there. Since then I’ve struggled to understand the nature of confinement and its effects on the individual.

It’s a striking and clear pattern that many of the most notorious terrorists of the modern era spent time in prison. Salah Abdeslam, the suspect behind the Paris and Brussels terror attacks, was imprisoned in Belgium with Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who lead the Friday the 13th attacks in Paris last November.

Chérif Kouachi and Amedy Coulibaly, responsible for the Charlie Hebdo and kosher supermarket attacks in Paris earlier in 2015, were imprisoned in France’s massive Fleury-Mérogis, Europe’s largest prison.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, before he became right-hand man to Osama bin Laden, was radicalised in Egyptian prisons. As Lawrence Wright, author of The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (2006), put it, Zawahiri ‘entered prison a surgeon. He came out of it a butcher.’

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was a petty criminal who became twisted in Jordan’s jails, and transformed finally into the vicious leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State, was held for nearly five years in Camp Bucca, the US-controlled prison in southern Iraq that became known as ‘jihadi university’.

José Padilla, Richard Reid, Jamal Ahmidan – add them to this grim but incomplete list.

Is prison a symptom in the lives of these individuals, or a cause? One thing is clear: these are the worst ex-convicts in the world. They compel me to think of the radical nature of prison itself. Prison, at least for a time, radicalises every person who experiences it.

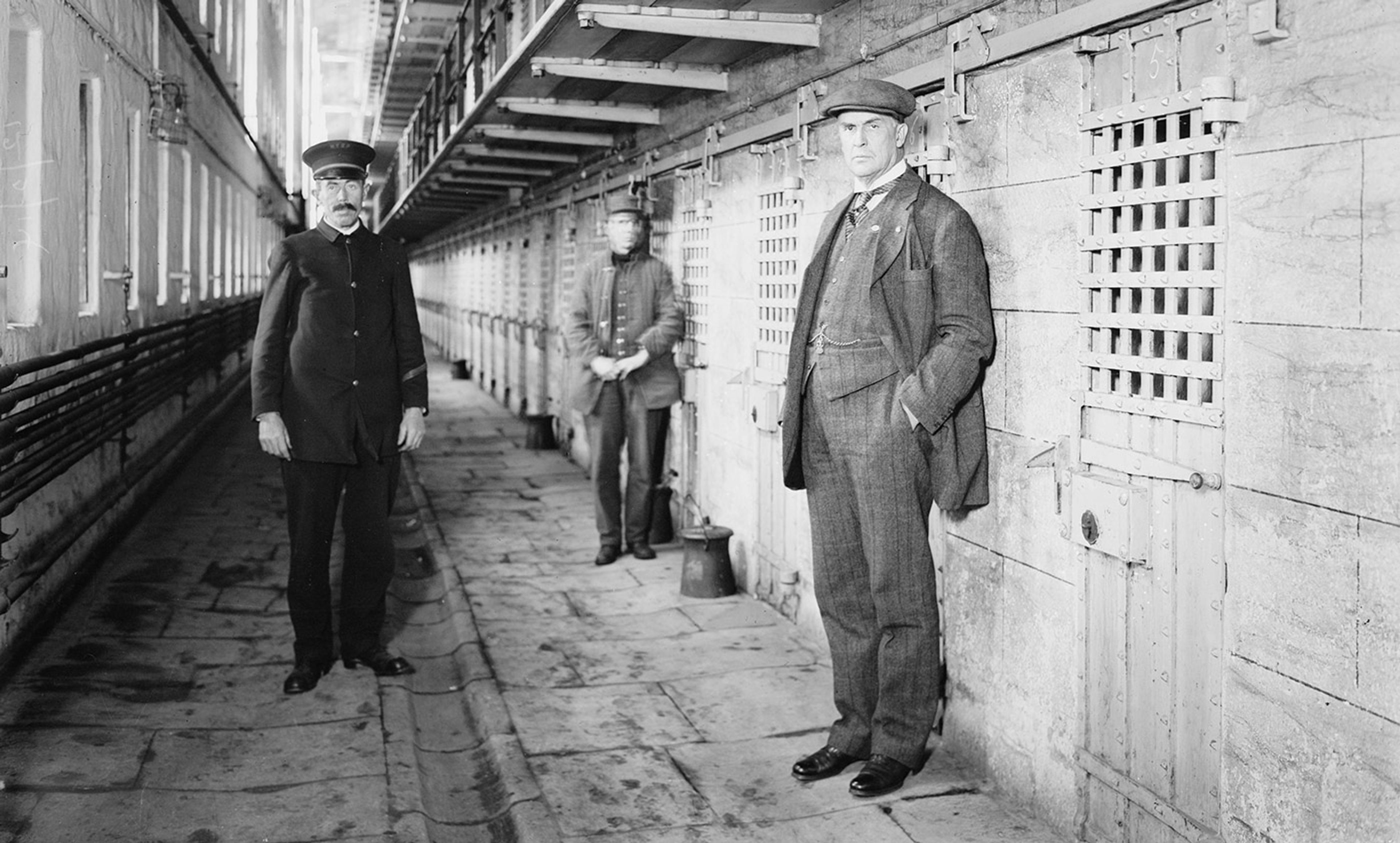

This is because most prisons are still radical entities themselves: medieval in their punishments and their settings, morally posturing, arrogating the right to torture and execute. Bars, shackles, isolation, daily acts of degradation. Only a few progressive countries have moved beyond this model. The US has not: Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, Camp Bucca – as well as the country’s supermax institutions stateside where solitary confinement is customary – are just the most extreme examples. Prisons are places of extreme vulnerability, and every inmate is susceptible to a hardening of grievance, spite and defiance.

In his report ‘Prisons and Terrorism’ (2010), published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, based in London, in partnership with the US National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, based in Maryland, Peter Neumann reviewed findings of studies on prisoner radicalisation in 15 countries, including Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, the UK, Spain and the US. One clear conclusion: any possibility of deradicalising inmates, or preventing radicalisation, requires stable and safe prison conditions.

With already actualised inmates, and those such as Abdeslam as he sat in a Belgian prison years earlier – stewing with potential for radicalisation – isolation does not work. Nor does warehousing as punishment, without effort toward rehabilitation. It’s the same for any inmate. Most penal systems, however, are still fixated on punishment, general debasement, and the blunt tool of deprivation of freedom.

For many of these extremists, their time in prison is a symptom, not a cause of their malevolent ways. But this misses the point. Most important is that once a criminal or terrorist is captured, the advantage and the opportunity belong to the state. The question is what to do with this opportunity.

As Neumann wrote in his report: ‘Often ignored by the public and policymakers, [prisons] are important vectors in the process of radicalisation, and they can be leveraged in the fight against it.’

Mark Hamm, a former prison guard and warden in Arizona and now a professor of criminology at Indiana State University, has studied prisoner radicalisation in the US and abroad. ‘The Madrid bombings really brought it together for me, this link between prisons and terrorism,’ he told me, referring mainly to Ahmidan, the leader of those attacks. Ahmidan was a hashish smuggler and career criminal who had spent time in prison in his native Morocco and in Spain. He met some of his bombing accomplices in jail.

‘I didn’t find a radicalisation problem in well-managed, medium-security institutions where inmates have rehabilitation programmes, drug counselling and work,’ Hamm said. ‘Where you find radicalisation is in overcrowded, gang-riddled, gladiator schools like Folsom [in California], Rikers Island and Clinton in New York, mismanaged old-time big houses.’

Is repression in itself – the deprivation of freedom – radicalising in a general sense? It can easily provoke one into a state of rage, regardless of the crime one had committed. This was true for me, for the first year and a half of my incarceration. Locked down 23 hours a day in a little cement cell, feeling debased and demonised, I found myself full of suppressed fury at the state, the ‘man’, the guards, the powers that be. Anyone who has ever been a prisoner is familiar with this territory of hate in the mind and heart. It’s prison’s worst work.

The US still has no official prisoner deradicalisation programme, unlike several European, North African and Middle Eastern countries. Yet the US has more than 400 domestic and international terrorists currently doing time in its prisons. Dozens are scheduled for release in the next five years.

These individuals were very much in mind when the Homeland Security Counterterrorism and Intelligence Subcommittee held a hearing in October 2015 on ‘Terror Inmates: Countering Violent Extremism in Prison and Beyond’.

During the hearing, Tony Parker, assistant commissioner of prisons at the Tennessee Department of Correction, testified that correction’s long-term strategy and foundation – security – might have become a liability. ‘We have failed to recognise the need to change the strategy to an approach that includes both security and a robust rehabilitative initiative.’

The long and growing list of international ex-convict terrorists represents simply the most conspicuous examples of the tens of thousands of inmates being released to the free world, all the time worse off than when they were sent away.

As long as prisons remain far more punitive than rehabilitative, they will create more political Islamists, more violent jihadists, more anti-government extremists, gangs and generally embittered and disaffected individuals of all stripes and faiths.