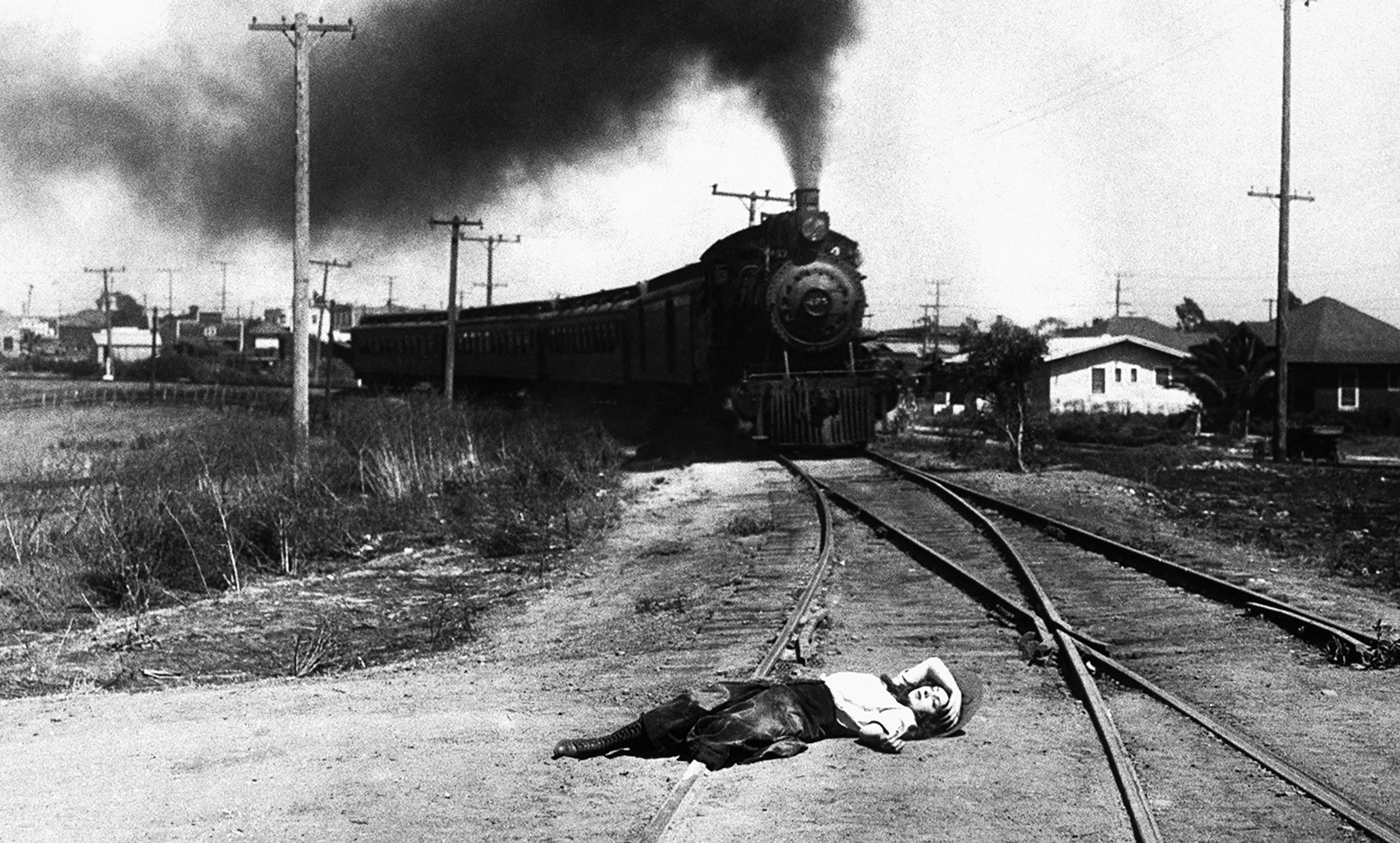

Photo by Marco Di Lauro/Getty

What should soldiers do in a war that ought not to be fought? Should they take part? If it’s wrong for one country to declare war on another, isn’t it also wrong for members of the armed forces to fight in that war? This is often true – but, surprisingly, it isn’t always true.

A war is a large-scale violent confrontation between groups of people. Typically, these groups have different aims, and members of those groups kill each other to secure their aims. These acts of killing partly constitute the war; without them, there wouldn’t be a war at all.

Let’s agree that a particular war is unjust. Normally, if a group activity is unjust, it is also wrong to perform the individual acts that constitute the group activity. So, if a war is unjust, it also seems wrong to carry out the acts that make that war. And it seems to follow that it is also wrong for individuals to fight in that war; if they do, they take part in unjust acts.

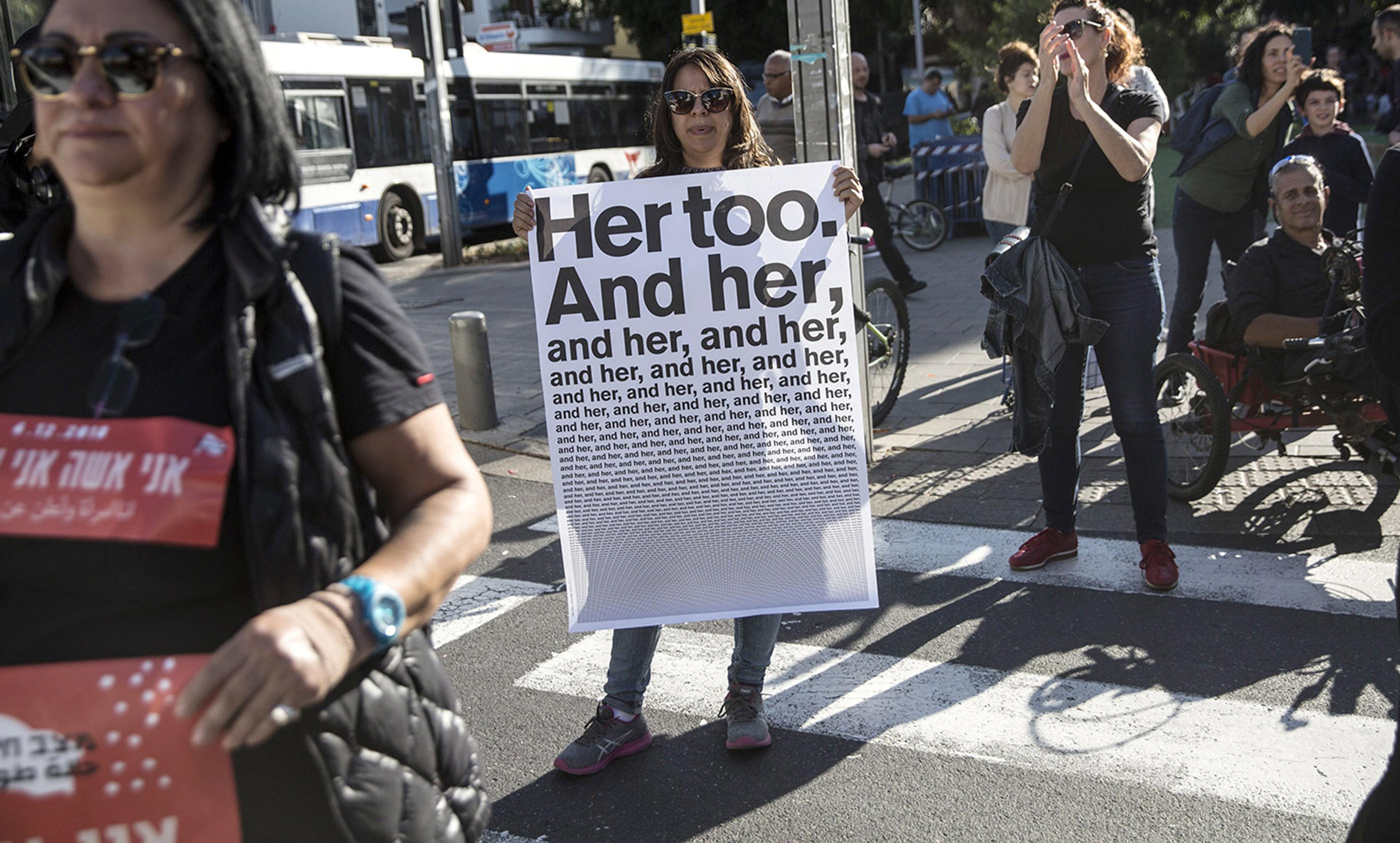

Yet it is quite common for people who oppose a war to support the troops that fight in them. This was often the attitude of those opposed to British involvement in the 2003 war in Iraq, for example. While many thought it wrong for the country to go to war, they didn’t condemn the professional soldiers who fought in that war.

One explanation for this attitude is that it can seem unreasonable to expect soldiers to evaluate whether the war they are involved in is unjust. But this explanation is, I believe, not very attractive. Suppose I conclude that the war is unjust. I have no more information than the troops do – possibly less. I, like them, draw my conclusions about the justice of the war from the publicly available evidence. If I draw the conclusion that the war is unjust, then I believe that the publicly available evidence warrants that conclusion. And if it does, then it warrants that conclusion for everyone who has the same evidence, including the troops.

Here’s another explanation. When people join the military, they commit themselves to follow their government’s decisions to go to war, irrespective of their own judgment about whether that war is unjust. And they get paid on that basis. On this view, even if it was wrong for the government to go to war, it was not wrong to go, once this wrongful decision has been made. But this argument is not very convincing either. A contract or a promise to act in a seriously wrongful way is not normally binding. War involves wrongful killing – an extremely grave wrong. It is hard to believe that anything like government authority, or the promises that combatants make to follow orders, are even close to being sufficiently important to justify a killing that would otherwise be wrong.

Yet even while these arguments are powerful and important, there can also be cases where a government acts wrongly in declaring war and – at the same time – the troops don’t act wrongly by fighting in the war. Remember, it is often wrong for governments to go to war because of the destruction they will cause. For example, many believed that it was wrong for Britain to go to war in Iraq because of the inevitable civilian casualties, and the chaos that could be expected after the war. So perhaps it would have been better if all the acts that constituted the war had not occurred.

But now consider an individual combatant. Whether she participates or not, the war will go ahead. The central questions for her are about the difference that her acts will make to the lives of others, not about the difference that all the war’s acts will make.

For example, an individual soldier who participated in the Iraq war might have decreased the war’s destruction. By making the invasion of Iraq more effective, she might have shortened the war, and her presence at its end might have helped to rebuild society from the chaos that inevitably results from war. If she did have these effects, her individual acts would not have been wrong, whatever the injustice of the war as a whole. Overall, she might have had good grounds for believing that her contributions would be positive.

Some might reject this argument, on the principle that we ought to act in the way that we want everyone to act. If we want no one to go to that war, we shouldn’t go to that war ourselves. But that principle is false. To see why, consider this: together, you and I can lift an injured soldier to safety, but I cannot do so alone. We might both want to do some lifting but that doesn’t mean that I still ought to if you won’t. My lifting alone might harm the soldier with no benefit. What I ought to do depends on what you will do, not on what you ought to do.

It could be objected that if a war is wrongful, people ought to stand up against it. And the best way of doing this is to refuse to fight. There is something right in this idea: if we are against the war, then protesting against it is valuable, and those who participated might not be in a very good position to protest. But, again, remember that life and death are at stake. If a person’s individual contribution to the war saves lives rather than costs lives, the value of protesting might be too small to make going to war wrong.

If it is wrong for a government to go to war, it is often wrong to fight in it. But sometimes, just sometimes, it can be right to fight in an unjust war to avoid a worse outcome.