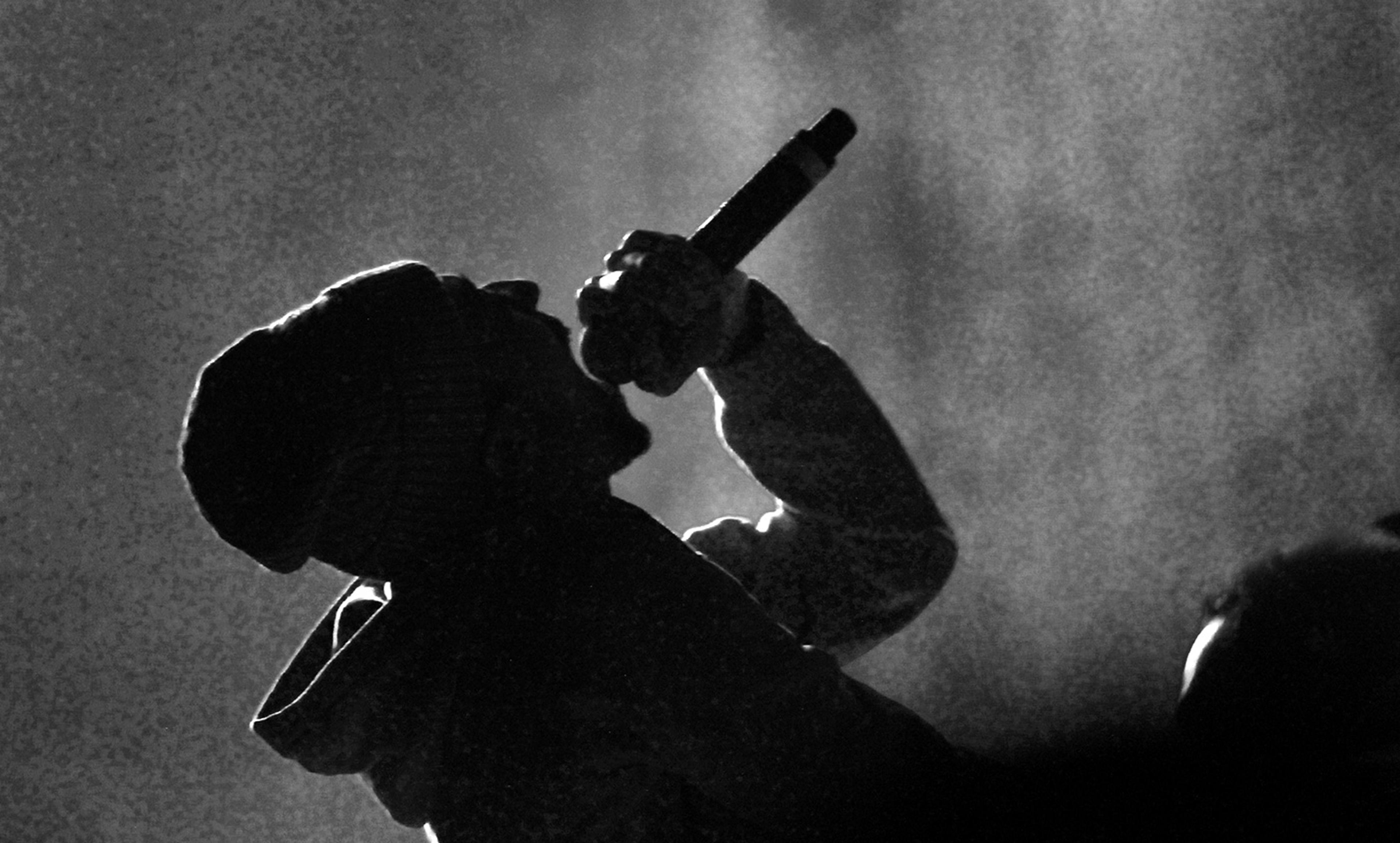

Mathys Cresson/Flickr

They showed up when Big Flossy was freestyling. At first, they kept to themselves, scanning the scene as if they were looking for someone. This made June Monsta nervous. He was standing next to me and told me that the two guys wearing oversized white T-shirts and fitted LA Dodgers hats were likely members of the Neighborhood Rollin’ 40s, a large local Crip gang. He watched them closely and said: ‘I hope they ain’t tryin’ to come out here with that gangbanging shit.’ A couple other regulars at Project Blowed – a legendary open-mic workshop – shared Monsta’s concern. They stood around nervously, waiting to see what these guys were all about.

And then, one of them edged his way into the middle of the freestyle session and tapped Big Flossy on the shoulder. Initially surprised, Big Flossy soon recognised his old friend. They dapped and the guy asked: ‘How come you don’t come around the ’hood no more?’ Big Flossy smiled and pointed to the corner, which was overflowing with MCs: ‘I been out here, on my hip hop shit.’

Big Flossy was one of many aspiring rappers I met at Project Blowed, a workshop that began in 1994 in South Central Los Angeles. I spent nearly five years in the scene, getting to know different young black men who had dreams of ‘blowin’ up’ or making it in the music industry. Each week, they performed original songs in the open-mic sessions, or freestyled with each other on the corner directly outside the club. Open Mike, a longtime regular, once compared Project Blowed to a dojo where martial artists train together. He said: ‘This is our dojo, where we come to train.’

Project Blowed was also more than just a lyrical training ground. It was a sanctuary for young men growing up in the shadows of Crips and Bloods gang violence. Big Flossy had grown up affiliated with the Rollin’ 40s. As a young man, he got jumped into the gang and identified as a gang member. But things changed once he got serious about hip hop. Once, while reflecting on his life, he said: ‘I was young and dumb back then. Just on some stupid shit. These days, I try to keep it moving – try to do something positive because this music is everything.’

Project Blowed offered Big Flossy and other young black men a safe space where they could hang out away from the menacing shadow of gangs. Across South Central LA in neighbourhoods such as the 40s, the 60s and the Jungles, police and gang members often ask youth if they are affiliated with a gang. ‘Where you from?’ or ‘What ’hood you bang?’ are questions that young people field every day. Answering these questions is not only a pragmatic issue, it’s also one that shapes their safety. Youth who answer this question incorrectly risk getting arrested, or attacked by rival gang members. At Project Blowed, nobody cared where you were from. All that mattered was if you had bars – that is, if you could rhyme.

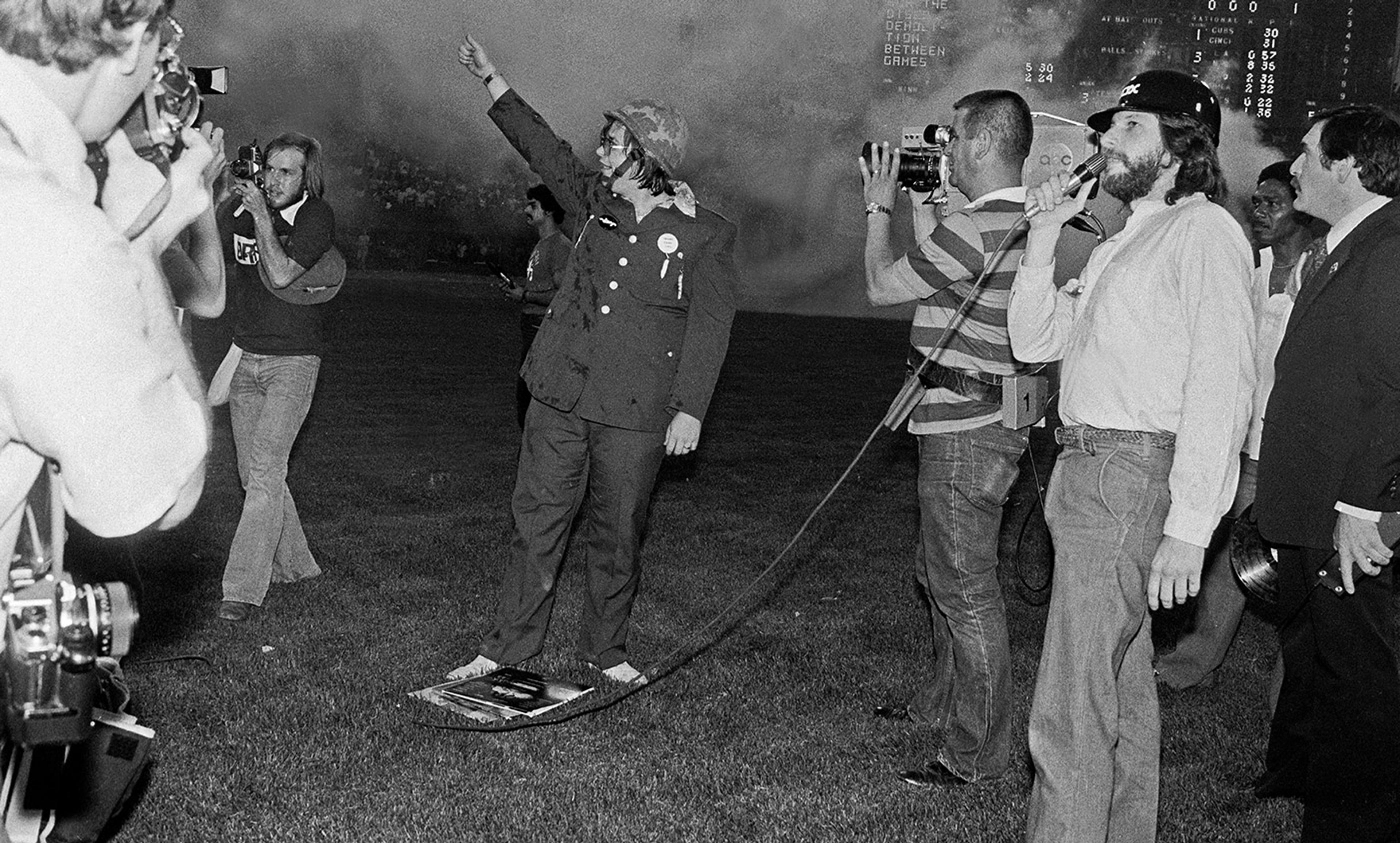

Project Blowed was one of many creative interventions hosted at KAOS Network, a community centre. Ben Caldwell, a filmmaker, community activist and local leader, founded KAOS in 1984, running it to enrich the lives of young people who went to public schools that often lacked music and arts programmes. Rappers respected him, and saw him as part of the community. They knew Caldwell met regularly with local vendors and police to ensure that the open mic had broader community support. He was the backbone of a youth intervention strategy that might not have been possible without a leader who commanded respect from so many different interest groups.

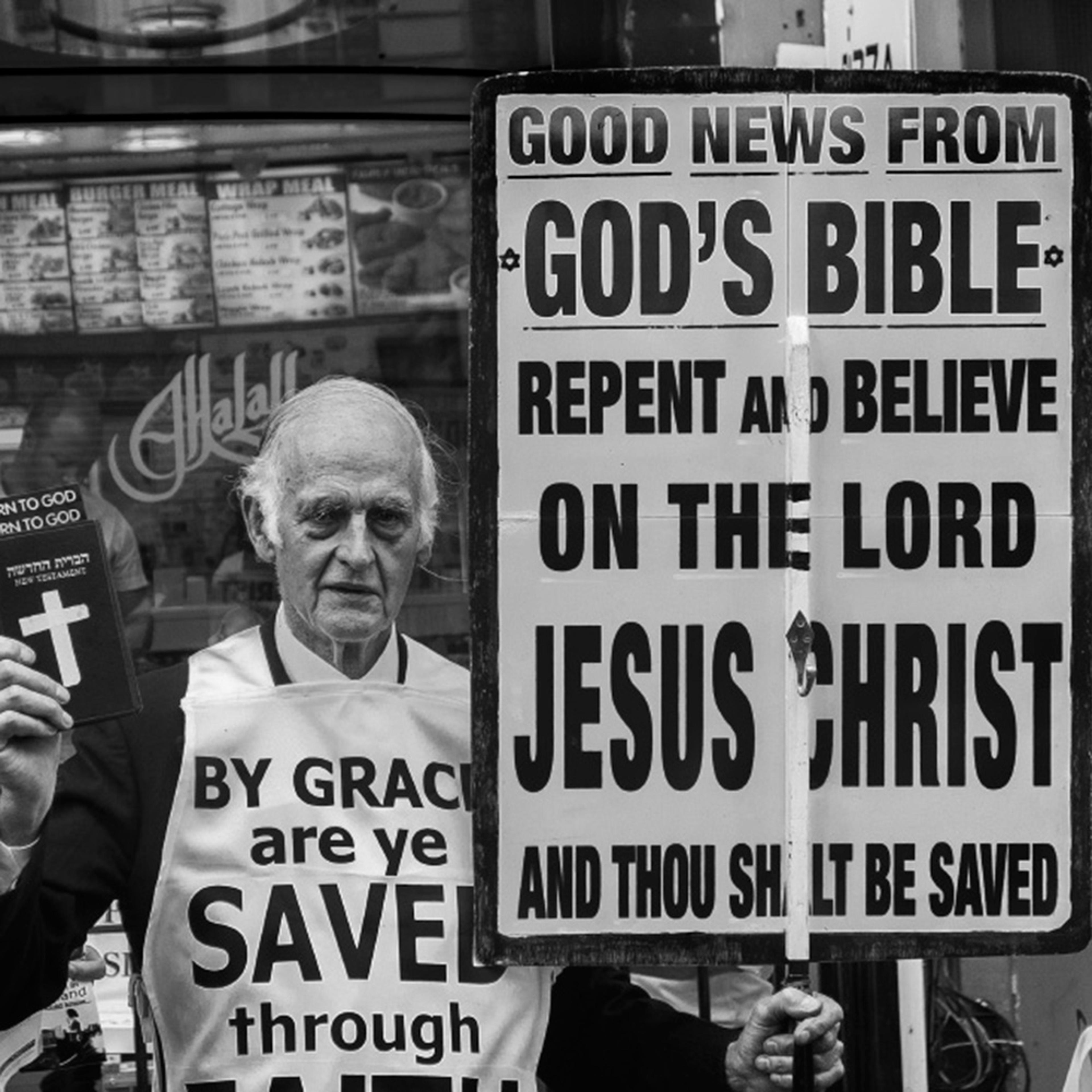

At an essential level, Project Blowed departed from punitive ways of dealing with the ‘gang problem’. I did my fieldwork during a time when LA was rolling out neighbourhood gang injunctions – restraining orders against suspected gang members. They prohibit suspected gang members from doing things that are already illegal, such as selling drugs and painting gang-related graffiti on buildings. They also criminalise routine activities such as using one’s cellphone in designated ‘hot spots’ of gang activity, and prohibit suspected gang members from congregating with other gang members in public.

Proponents argue that these measures create an environment that’s hostile to gangs and the routine activities needed to sustain them. But these measures are notoriously vague. They create a system that increases the chances for racial profiling.

These issues came to a head recently, as the LA City Council approved a $30 million class-action settlement against the LA Police Department for illegally imposing curfews on suspected gang members. One of the original plaintiffs in this lawsuit, Christian Rodriguez, had been placed on an injunction list without ever having been in a gang.

Project Blowed was a local activist’s solution to gang violence. Instead of ramping up efforts at monitoring, arresting or punishing young people, it made positive and creative possibilities available in their lives before they were at risk to join gangs. Though it came from the community, Project Blowed was also much bigger, setting people’s sights on the world outside, and supporting aspirations and identities beyond the gang world. Perhaps more than anything, it provided an opportunity for young men who might have been sworn enemies in other aspects of their lives to collaborate and make something. That’s an example the world needs.