Frantz Fanon. Photo by photographymontreal

Is there any point thinking about what to do? It is often said that our judgments and behaviour are really caused by immediate intuitions and gut feelings, with reasoning happening only afterwards. But that claim misses an important point. Experiments also indicate that reasoning shapes the cognitive system that produces future responses. The more we reason that something is good or bad, right or wrong, attractive or unattractive, the more influential that attitude becomes over our intuitions and gut feelings.

Aristotle would not be surprised. His ethics rests on his idea that character develops in precisely this way. Aristotle’s view, however, does not explain how your thought and behaviour can be influenced by social stereotypes that you do not endorse in your own reasoning. We can understand this process better if we turn to the idea of sedimentation developed by three French philosophers in the middle of the 20th century.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty coined the term ‘sedimentation’ in his book Phenomenology of Perception (1945). He uses it to describe the process of taking on information about our bodies and environment in a form that enables us to act intelligently without much attention, effort or thought. Just as a river accumulates particles and deposits them as sedimented structures that direct the river’s flow, argued Merleau-Ponty, so we accumulate information as we go about our lives, which gradually and unconsciously builds into a contoured bedrock of understanding that guides our behaviour.

Merleau-Ponty’s work helps us to see how our behaviour can be influenced by stereotypes that we do not agree with. For if this sedimentation process is insensitive to whether we are interacting with the world itself or with media representations of it, then stereotypes occurring regularly in our media will become integrated into our worldview along with knowledge of the real world. Because he focused on knowledge, Merleau-Ponty did not develop a theory of the sedimentation of goals and motivations. He did suggest that these might become sedimented in a similar way to knowledge, but he did not explore the idea in detail.

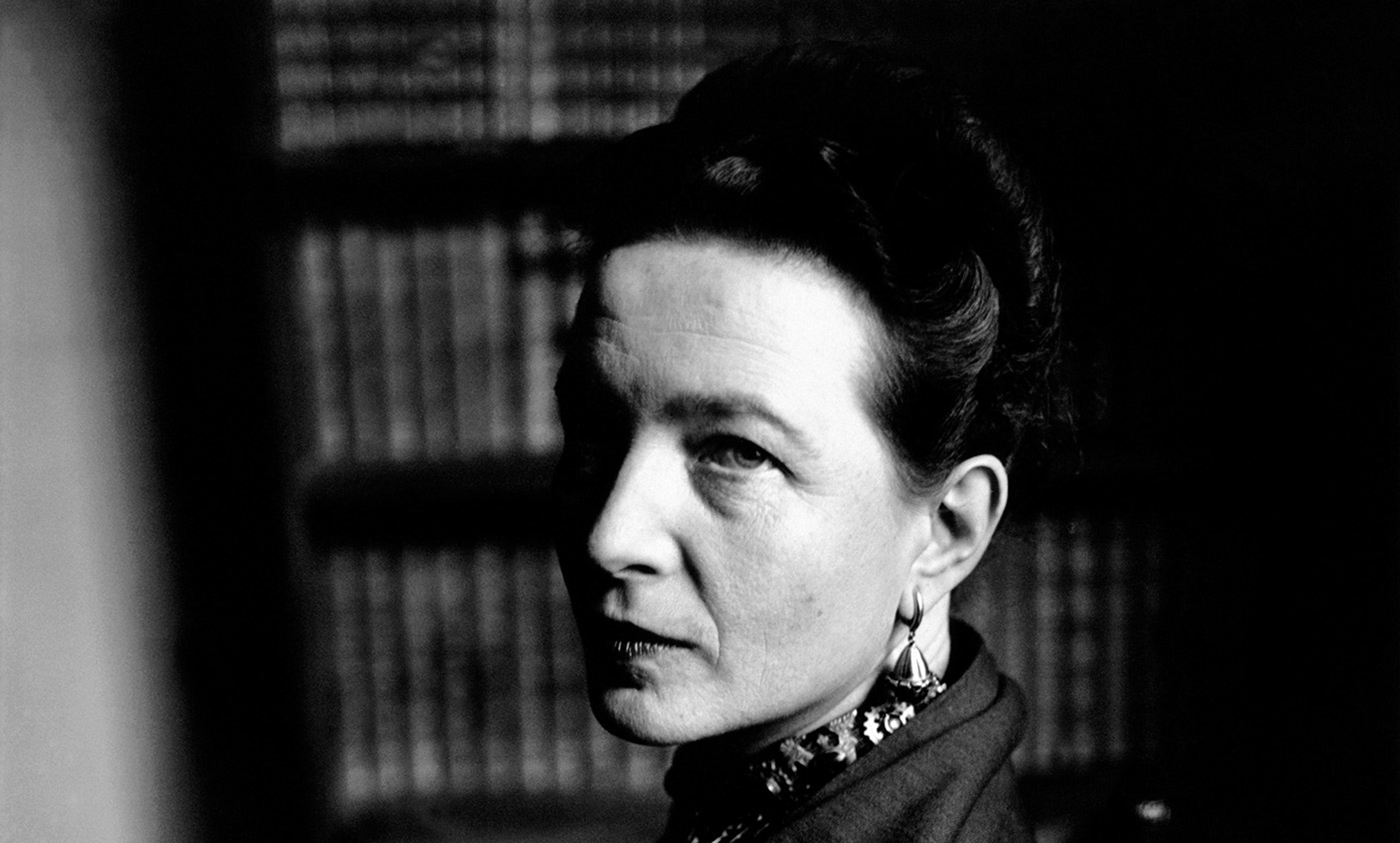

For a unified account of how our behaviour can be effortlessly influenced by our own repeatedly endorsed motivations and by social stereotypes that we do not endorse, we can turn to the existentialist writings of Simone de Beauvoir and Frantz Fanon. De Beauvoir articulates her version of sedimentation most fully in The Second Sex (1949). Her focus is on how we develop our goals and values. Girls and boys are raised with different expectations and inducements, and so are continually encouraged to think and act in ways that fit their assigned gender. Girls are required to respond to their environments in pleasing and helpful ways, whereas boys are encouraged to explore and dominate theirs.

These expectations shape the goals and values that we pursue across childhood and adolescence. De Beauvoir argued that this repeated endorsement of the same goals and values embeds them into our cognitive systems through sedimentation. Because girls and boys are subject to different expectations, we develop gendered sets of goals and values. De Beauvoir argued that the same process also embeds gender stereotypes into our outlooks. As our goals and values become sedimented through repetition, so too do our strategies for achieving them. These strategies encode information that helps us navigate our world. And this information includes the gender stereotypes that people are expected to live up to.

So gender stereotypes themselves become sedimented in our minds along with the goals and values that make our behaviour conform, more or less, to those stereotypes. It is because the stereotypes have themselves become embedded, argued de Beauvoir, that they are perpetuated in the ways we raise the next generation. And for the same reason, it is difficult to avoid sometimes manifesting these stereotypes in thought and action, even when we explicitly reject them.

Fanon presented a similar account of the origins of racial identity in his book Black Skin, White Masks (1952). He described the stories and films common to childhoods across France and the French colonies in the first half of the 20th century, including in his own upbringing in Martinique. These tended to show Europeans as heroic and sophisticated. By contrast, when Africans were presented at all, they were shown as inferior and dangerous.

All children in France and the French colonies, regardless of skin colour, were explicitly taught in school to consider themselves French and therefore as European. They were taught about European history and literature. They were encouraged to develop goals and values consonant with this European identity. Fanon argued that the combination of this with the imagery in stories and films inculcated an idea of European superiority and African inferiority in everyone brought up this way.

It is no coincidence that de Beauvoir, Fanon and Merleau-Ponty all developed versions of the idea of sedimentation. De Beauvoir and Merleau-Ponty had been friends since they were students together, and developed their varieties of sedimentation in continuous discussion over 15 years. Fanon developed his while studying at the University of Lyon, where he attended Merleau-Ponty’s lectures.

The version of sedimentation that de Beauvoir and Fanon argued for is specifically existentialist. It is our chosen motivations, along with strategies and information for acting on them, that become sedimented. But our sedimented ideas and goals are not the only influences on our thought. By considering other people’s ideas or taking up a critical perspective on our own ideas, we can formulate conclusions at odds with our sedimented outlook. This explains why inattentive aspects of our behaviour can manifest sedimented stereotypes that we do not endorse. But it also indicates how we can take control of the intuitions and feelings that drive these aspects of our behaviour.

If the existentialism of de Beauvoir and Fanon is right, we are not the puppets of inherited ideologies. We can reason about the attitudes that matter most to us, and we can reform our social environments. In both ways, we can actively reshape the sedimented outlook that guides our behaviour.

Rethinking Existentialism by Jonathan Webber is published via Oxford University Press.