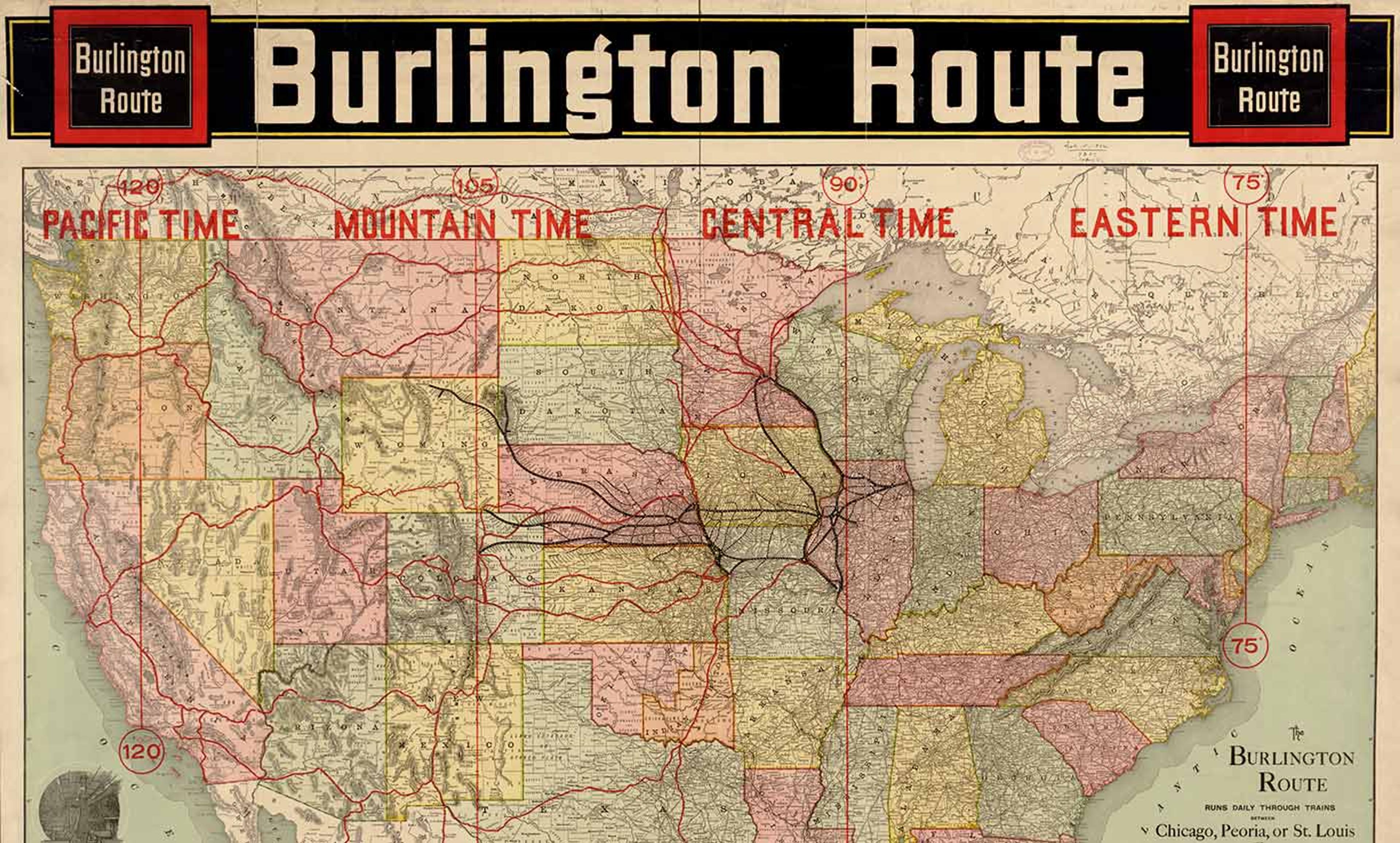

Stop that car! Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave Sarajevo Town Hall immediately prior to his assassination on 28 June 1914. Courtesy Wikimedia

When we think of the future, it very naturally seems to be ‘open’ – a realm of unfixed possibilities, awaiting the choices we make now. But are we right to think about the future this way?

Some philosophers argue that the only way to explain the differences in how we look at the past and future is to employ a certain ‘metaphysical’ picture of time. According to this view, time itself is unfolding, and the future has very different basic properties from the past. According to a ‘growing-block’ theory of time, for example, events in the past and present exist, but events in the future do not – they are yet to be. The reason, then, that we think of the future as open is that it doesn’t exist yet.

But there are at least a couple of problems with this metaphysical approach. Firstly, it doesn’t fit well with science. Fundamental physics doesn’t indicate that there’s anything like a growing-block picture of time, or any kind of account where time itself changes. From the point of view of physics, future events are just as real as those in the past and present – even if we can’t engage with them.

There’s another problem with using a metaphysical picture to explain why the future seems open. Human minds aren’t geared to intuit what fundamental reality is like. Typically, it takes a lot of empirical work to figure out the way things are. It was very natural at one time to think of air as weightless, and of solid objects as filled with matter. But we’ve learnt that air is weighty, and that solid things are mostly empty space – even if we can also make good sense of why these things seemed otherwise. Given these lessons, it would be very surprising if we had direct insight into the fundamental nature of time.

So what else might explain why the future seems open? My own approach is somewhat unusual. I think about cases of hypothetical time travel, particularly cases where someone journeys backwards in time to interact with events that happened before she left. The broad consensus is that such time travel isn’t going to happen in our world, at least not anytime soon. But philosophers, particularly since David Lewis, the American author of On the Plurality of Worlds (1986), have argued that such cases are nevertheless logically possible – they are conceptually coherent. Using just a single timeline, we can tell consistent stories involving time travel. Under this approach, time travellers don’t go back and change events from being one way to being another, as in the film Back to the Future (1985). Instead, time travel is more like what you see in 12 Monkeys (1995): it was always already the case that the time traveller was there in the past, participating in the events that made the future the way it is.

What can time travel teach us about the open future? Firstly, time travel suggests that the apparent openness of the future is a ‘perspectival’ affair – it depends on what point of view you adopt. Say you’re watching Doctor Who disappear in her time machine on New Year’s Day in 2020. From your perspective, the events after New Year’s Day are changeable, while the events before New Year’s Day are not – so only the future appears ‘open’. But take the perspective of Doctor Who. She can affect events in the past. She can decide where to land, whom to see, and what to do. So aspects of the past will seem ‘open’ to her. Because time travellers and the rest of us travel on different paths through time, different parts of time will seem open. If so, it’s not a metaphysical feature of time that explains what seems open. Instead, it’s how we move through time, and what events we can influence.

Does it follow that the apparent openness of the future boils down to what you can influence? The fact that causes always come before their effects (in our world) does much to explain the way we look at future events. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. Imagine again you’re in a world where you can travel back in time, and are distressed about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. So you jump into your time machine, zip back to 1914, and try to prevent the assassination. The standard argument from Lewis is that you can indeed prevent it. Why? Because, once you’ve travelled back in time, the assassination is something you can causally influence. While it’s true you won’t succeed at preventing it (given we know that the assassination occurs), this doesn’t mean you’re not able to – but, after all, we often can do things that we don’t succeed at. If Lewis is right, then, and if causation alone explains our intuitions about time, then time travellers will experience the whole future as open.

But, to my mind, this isn’t quite right. A time traveller who knows perfectly well what’s going to happen cannot reasonably consider all future events to be up for grabs. Having lived through the consequences of Ferdinand’s assassination in 1914, and by having records of its occurrence independent of the choices she makes now, a reasonable time traveller will be certain that the assassination occurs – regardless of what she does or doesn’t do. So the whole future won’t seem like an open question.

If this argument is correct, the reason why the future appears open to us isn’t merely because we can causally influence it. It’s also because we don’t have memories and records of the future in our world. Part of what contributes to our sense that the future is open, then, seems to be our ignorance of it.

But perhaps all this is beside the point: time travel isn’t a practical possibility at the moment, so it doesn’t do much to inform us about our current experience of the future. However, there are other ways we might end up having reliable knowledge of the future. If machine-learning algorithms become extremely advanced, they might be able to reliably predict not only general trends about what we’ll do, such as our spending habits, but also particular choices, such as what car we’ll buy, where we’ll send our kids to school, and where we’ll choose to go on holiday.

Imagine you were told what your next major purchase would be. You might think that this would have no effect on your apparent freedom. Surely you can change your mind and decide some other way – especially since the prediction has been revealed to you. But imagine the prediction is made in minute detail, and reveals not just one choice, but the full future history of your life, stretching out before you. And imagine the predictor knows how to take into account the effect your knowledge of its prediction will have on how you decide. My hypothesis is that encountering such predictions would have a deep effect on our experience – and would start to erode our sense of the malleability of the future.

I’d need to say much more to make this account truly convincing. What I hope to have shown, nevertheless, is that it’s an important intellectual project to explain our experience of time in the actual world. Time-travel cases are crucial here, because they allow us to think through how asymmetries in our experience of time might relate to one another. Even if time travel is mere science fiction, it supports scientific work in the here and now.