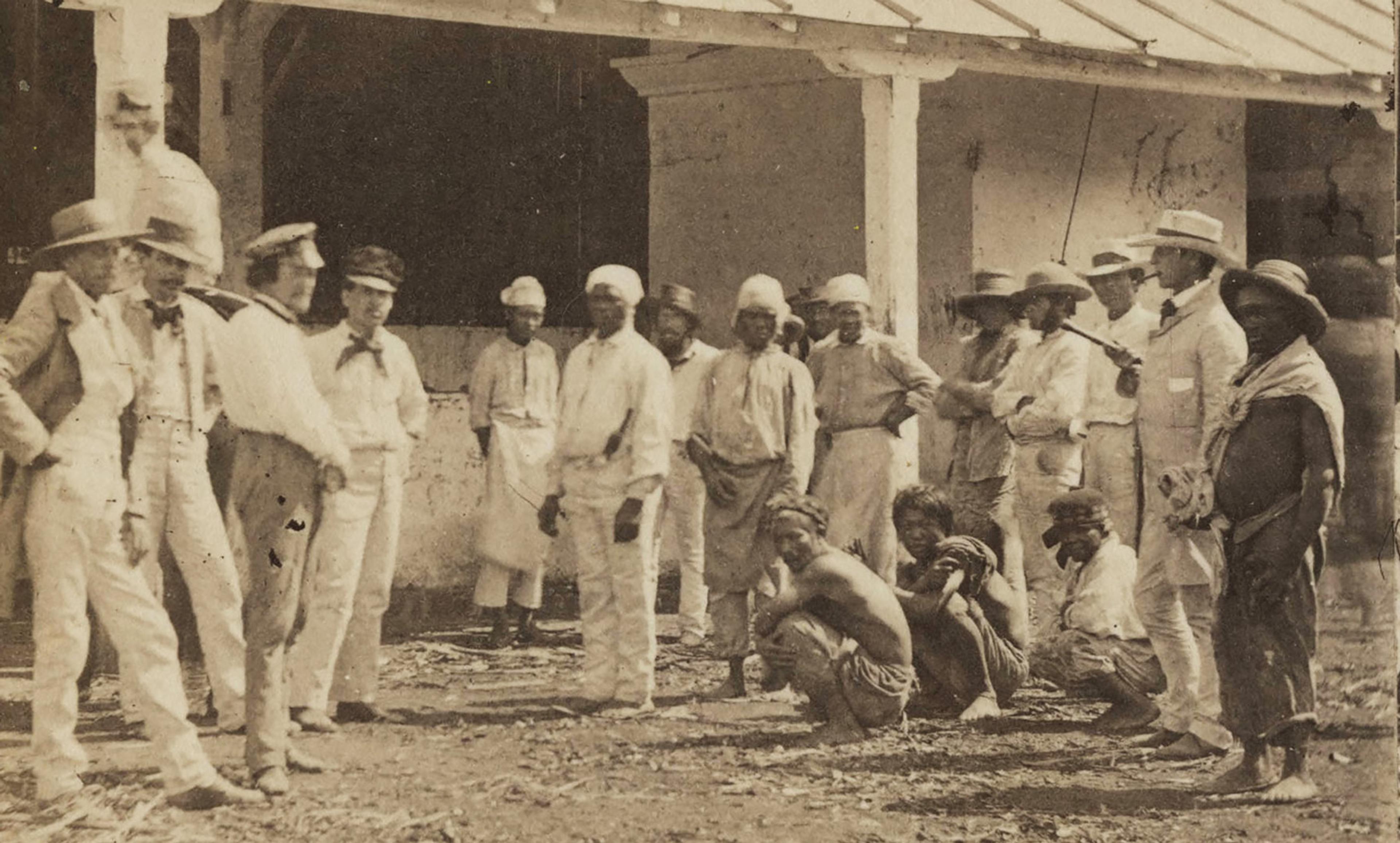

Plantation Høgensborg on St Croix in the former Danish West Indies (1833). Courtesy Wikipedia

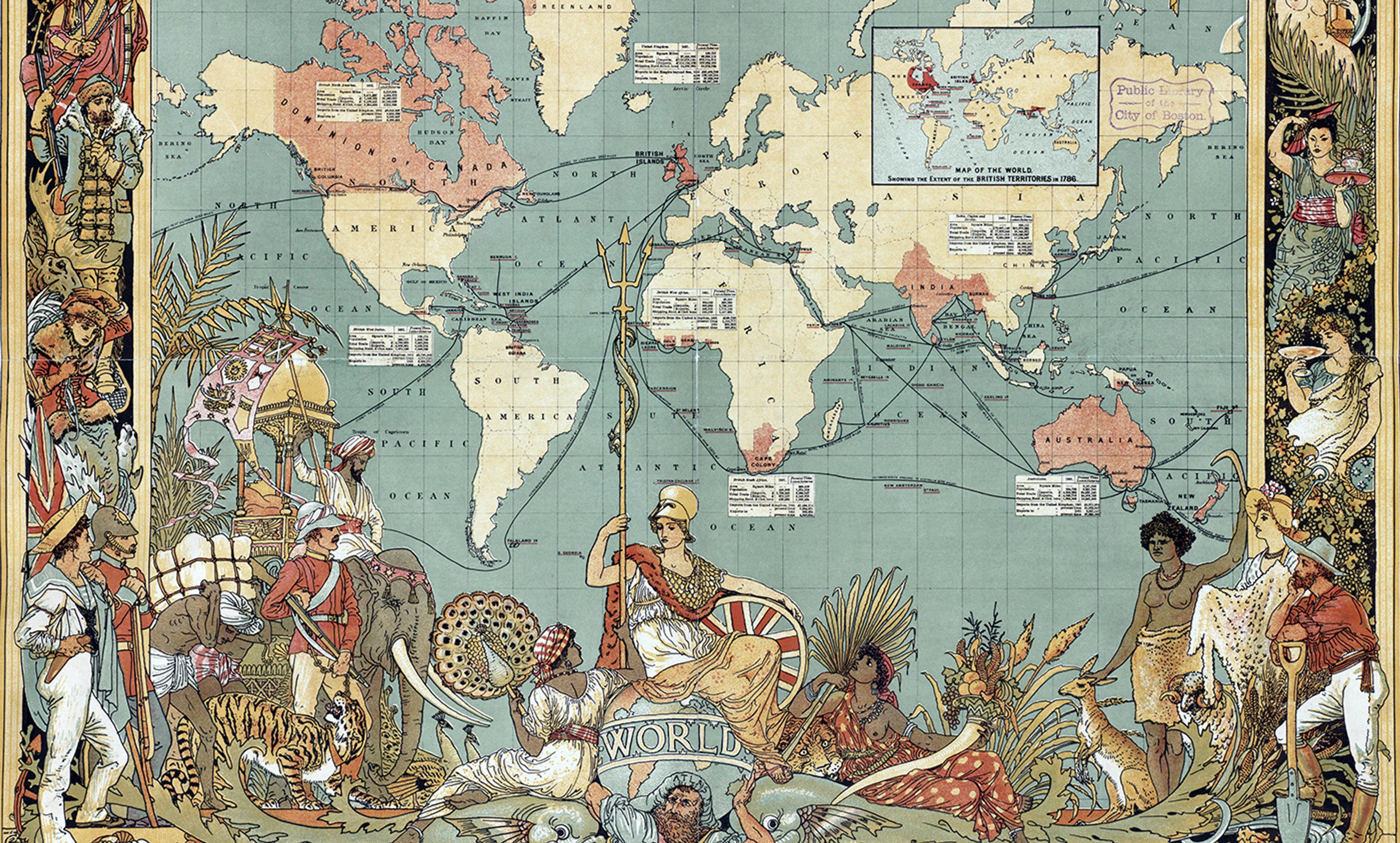

For many of the most successful imperialist countries, empire was just not worth the trouble. Scandinavian monarchies in the 17th and 18th centuries endeavoured to build empires that would rival the Dutch or even the British, but come the 19th century they sold up the remnants of these overseas ambitions, and largely escaped the administrative responsibility, and moral condemnation, for the age of High Imperialism. Nevertheless, though they gave up administering colonies, a closer look reveals that, by hitchhiking on the back of the British, French and German empires, the little Scandinavian monarchies benefitted greatly from European colonialism. In profound ways, talking of a European colonialism, or a colonialism enriching a collective Europe, makes sense.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, European monarchs speculated on the economic potential of overseas colonies. Trading companies, owned or backed by governments, built trading posts and administered land at the fringes of European exploration. British, French or Dutch empires were not the only speculators. Denmark established 30 forts, lodges and stations along the West African Coast. Between 1626 and 1825, Danish vessels shipped almost 100,000 enslaved Africans through these Scandinavian forts. The Danish East India Company held posts as far from Jutland as Tamil Nadu and Bengal, and settled three sugar islands in the Caribbean – the ‘Danish West Indies’ – while Sweden took the Caribbean island of St Barthélemy.

Under 18th-century mercantilist empires, these trading companies and their forts, monopolies and gunpowder were the only legitimate way for a country to funnel profits from the New World (and Africa and Asia) into their treasuries. Navigation Acts aimed to ensure that raw materials and investments of empire moved only between ‘mother country’ and ‘colony’. Smaller countries were shut out of the most lucrative lands in, say, St Domingue or Barbados. This left them to establish their own ventures in the leftover or marginal spaces. Scotland, for instance, shut out of trade with English colonies, tried to make good the swampy, gnat-infested, Darién gap in modern-day Panama at the end of the 17th century. After the Darién colony failed, Scotland turned in 1707 to formal Union with England. Monarchs in Copenhagen and Stockholm tried to establish their own colonies to face a powerful world of mercantilist competitors.

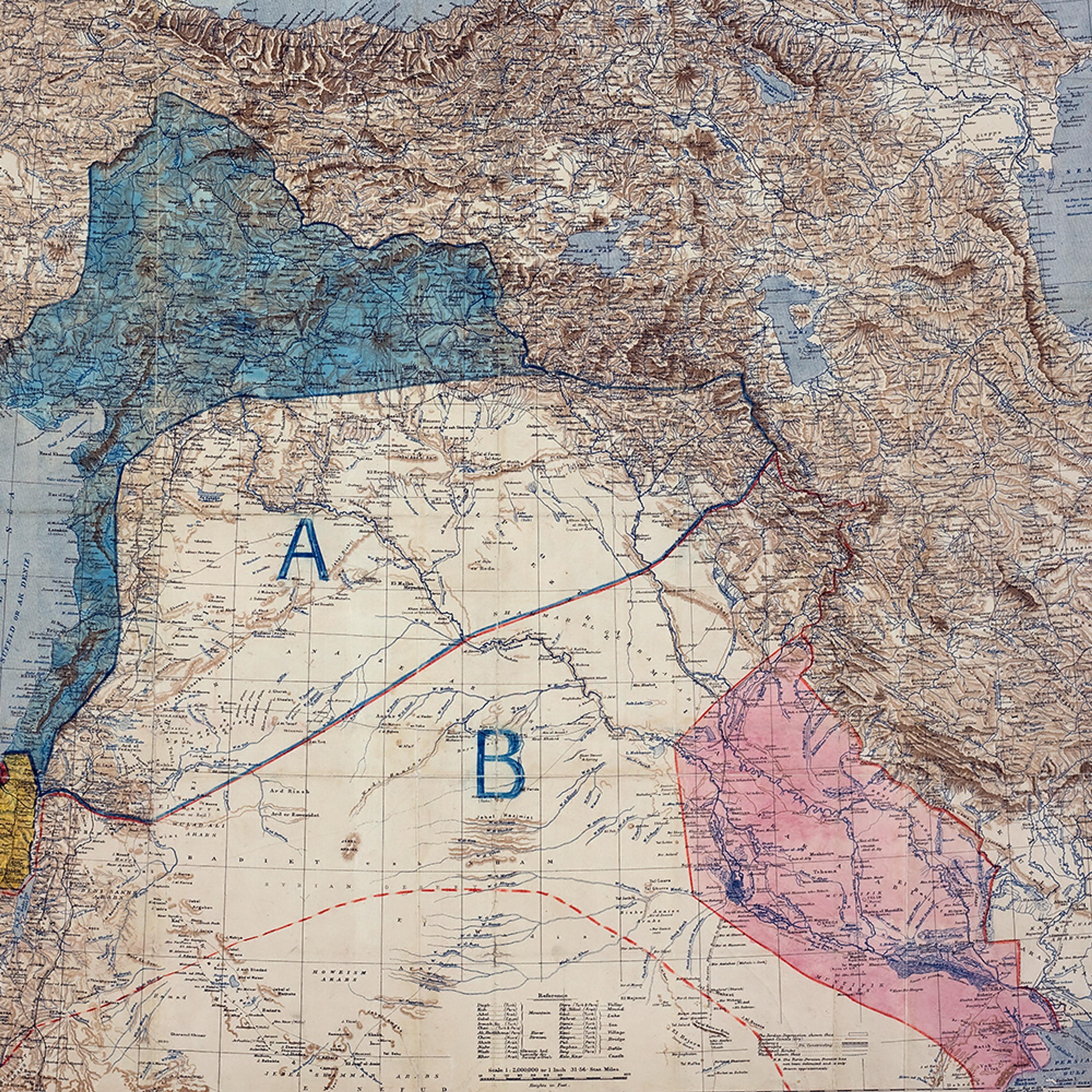

In the 19th century, change came not from moral awakening but new commercial realities. The devastation wrought by the Napoleonic Wars left Great Britain the world’s dominant military and industrial power. By advocating free trade, Britain made possible a new style of imperialism. Free trade, even when diluted, rendered the administration of territory unnecessarily expensive for these little monarchies. Markets opened by British gunboats, especially in China and the Americas, were also open to other European shipping. Canals, then railways, steamships and telegraph lines helped in globalising the world economy. Connecting these local economies created specialisation of function: vast areas of the American South, India and Egypt devoted to the cash-crop cotton; gold rushes in California, the Transvaal and Melbourne. Though it’s less recognised, globalisation also led to specialisation of function among imperialists.

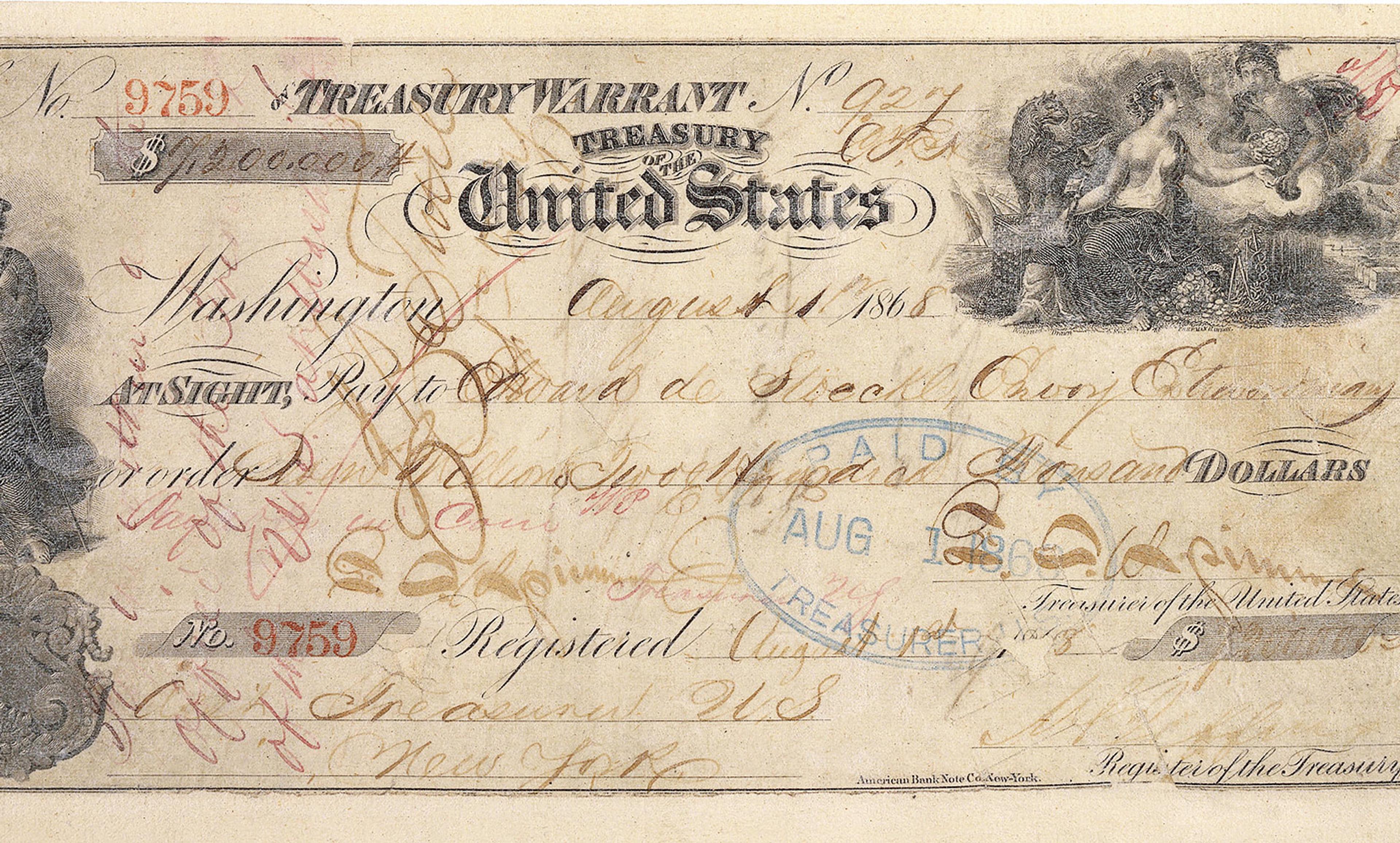

Danish and Swedish merchants and state trading companies no longer needed their own exclusive territories because now they could access bigger and wealthier British imperial markets. They sold up and ‘hitchhiked’ instead. Denmark sold its possessions to Britain (Trankebar and Frederiksnagore in 1845, the West African forts in 1850, the Nicobar Islands in 1869) and the United States (the US Virgin Islands in 1917). Sweden sold Saint Barthélemy to France in 1878. Rather than a diminishment of overseas aspiration, as such divestments might appear, these sales resulted from the logical consequence of an ambitious global policy. Instead of engaging in colonisation – for controlling and governing territory is among the riskiest and most expensive aspects of empire – they ‘outsourced’ this function to bigger European powers.

Kirsten Alsaker Kjerland and Bjørn Enge Bertelsen’s excellent edited volume Navigating Colonial Orders (2014) shows how Norwegians used ‘hitchhiking’ to thrive in a world of empires. In 1878, Norway was the third largest nation globally in terms of shipping tonnage, behind only Great Britain and the US. Norwegians ran farms in Kenya, and whaling enterprises in South Africa. Around 1,000 Finns migrated to work in mines in German Southwest Africa.

Owen and Eleanor Lattimore first used the term ‘hitchhiking imperialism’ in The Making of Modern China: A Short History (1944) to describe the US in China. British and French gunboats secured trade access in 1842, following the Opium Wars, and the US, through the 1844 Treaty of Wanghia and John Hay’s ‘Open Door’ policy of the 1890s, joined these networks. US railways, missionaries and investors established themselves in China without significant US military presence by sailing (or ‘steaming’) in the wake of Britain’s Royal Navy.

Imperialists came in many different varieties in the 19th century. Scandinavia and the US (outside of North America) point us to a more sophisticated understanding of empire. Some imperialists administered territory and opened markets. Others provided capital to build railways and link the global economy. Still others produced migratory labour or hauled commodities. Administering territory was the most prestigious job. But it was not the only way to be an imperialist. Profit and power could also be won by hitchhiking.

The Scandinavians are still hitchhiking away. The Danish shipping line A P Moller-Maersk is the largest in the world, moving more than 12 million shipping containers around the globe every year. Oil profits fund Norway’s $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund, which is in turn invested worldwide. Nowadays, they hitchhike on a Pax Americana rather than a Pax Britannica, but it is important to remember that small, globally orientated European countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Norway exist because the arrangement of world geopolitics leaves them a particular space in which to thrive. More than a century after they sold their colonies, the hitchhiking strategy still seems to be paying off.