Royal Museum Greenwich

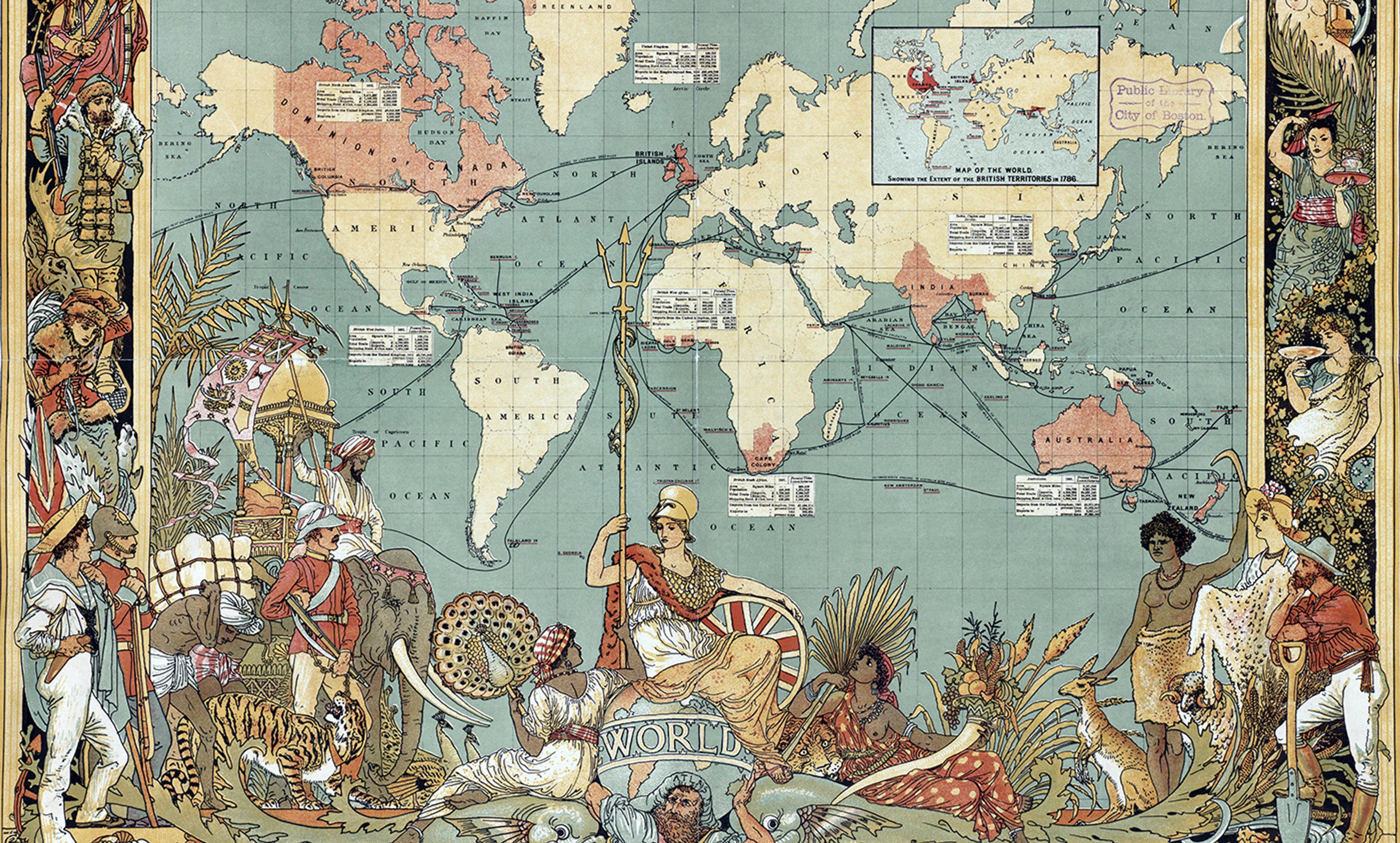

The British empire never lacked contradictions. A global juggernaut standing with its military boot on millions of necks, practising commercial coercion and diplomatic cynicism, it nonetheless routinely thought of itself as a plucky underdog. Its heroes were the handful of redcoats at Rorke’s Drift fighting off the Zulu masses, or General Charles Gordon of Khartoum, going down against the odds in a last stand against religious zealots in the Sudan.

British soldiers, diplomats and traders pictured themselves as almost accidental conquerors, vanquishing a quarter of the planet’s landmass in between tea, tiffin and cricket matches. They maintained a detached stiff upper lip and publicly ignored the unpleasant reality of the Maxim gun – a luxury not afforded to the locals on its business end.

Britain preferred to see its dominance of a fifth of the world’s population as some sort of benevolent, God-given mission to bring law, order and free trade to benighted corners of the world. As George Bernard Shaw complained: ‘The ordinary Britisher imagines that God is an Englishman.’

It was a powerful notion and it has not gone away. Even though the Empire is reduced to a scattering of tiny islands with names few Britons would recognise, the imperial past remains implausibly popular. Early this year, a poll showed that a full 44 per cent of Britons were proud of colonialism, far outnumbering the mere 21 per cent who regretted their country’s imperial past. The survey was not an outlier. A 2014 report showed a mere 15 per cent of Britons thought the colonised might just have been left worse off by the experience.

Popular sentiment marches here with intellectual officers. Tristram Hunt – a Labour MP – has just published a book celebrating the urban legacy of Empire in such cities as Mumbai, Singapore and Dubai. The historian Niall Ferguson has made a cottage industry out of defending Empire and posits it as a force for good that kept other, nastier European powers at bay. Though – one might politely suggest – you should try telling that to the dead of Amritsar. Or the Afrikaners in their concentration camps. Or the Chinese addicts who fell victim to Britain’s desire to defend her trade rights in opium.

Nostalgia for Empire permeates popular culture, too. One of the great recent hits of British TV is Indian Summers – a celebration of the Raj lifestyle as it follows the antics of colonial officials in the old summer capital of Shimla. Downton Abbey fetishises the 1920s aristocracy and their way of life, worshipping at the feet of the world conquerors. One of London’s top Indian restaurant chains – Dishoom – attempts to recreate the café culture of 1920s Bombay. The interior design of Gymkhana – voted best restaurant in Britain in 2014 – mimics the colonial style, complete with hunting trophies and ceiling fans. The movie The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011) – and its inevitable sequel – portray the ex-colonies as the warm and welcoming place where one can go to find the good life.

Britain’s warm bath of imperial nostalgia also masks some harder truths. Like the empire itself, this nostalgia is not quite what it pretends to be. For a start, those many restaurants mining the rich vein of imperial fantasy are usually owned by Indians, or Britons of Indian descent. Look at the strange fate of the East India Company – the once mighty corporate face of empire still lingers on as an Indian-owned purveyor of colonial-inspired fine foods and teas.

Now it is Britain itself that is being colonised, and the ones doing the invading are the forces of international capitalism, often in the form of the ultra-rich from the former colonies. Legions of greenbacks, not redcoats, are the new means. Foreign money, not conquered resources, is flooding into London. The old imperial capital made too good a fist of becoming the world’s centre of global finance by exploiting its old territories, and now some of them are roaring back with a vengeance.

Middle Eastern, Asian and Russian cash is warping London’s property market beyond recognition. Harrods – once the consumerist pinnacle of imperial grandeur – is a bauble for Qatar (who bought it from an Egyptian). British football teams, which have long symbolised gritty working-class values, have become vehicles for the personal and national ambitions of Russian oligarchs, Asian businessmen and Gulf states alike. Grotesque inequality is a byword for life in the British capital as local councils, aghast that social housing for the poor sits on their suddenly invaluable real estate, plot to knock down council flats and replace them with luxury apartments. Their prospective overseas owners will probably never step through the front doors. Indian owners sell off their British steel operations, plunging the government into crisis and threatening thousands of jobs.

Even the idea of Britishness is morphing. It is being adopted most enthusiastically by immigrants to the United Kingdom, often from former colonies, and viewed increasingly skeptically by the old imperialists themselves. In a more and more disunited kingdom, the very first colonies in the shape of the Welsh and Scottish are also straining at the yoke with their own parliaments and powers. The English themselves might be the final nation to free themselves from the British empire. As they dream of a sepia-toned vision of a past that never was, it is no longer just the latest contradictory expression of an empire that always refused to admit to itself its true intent. It is also now a refuge from an increasingly uncomfortable and ugly present.