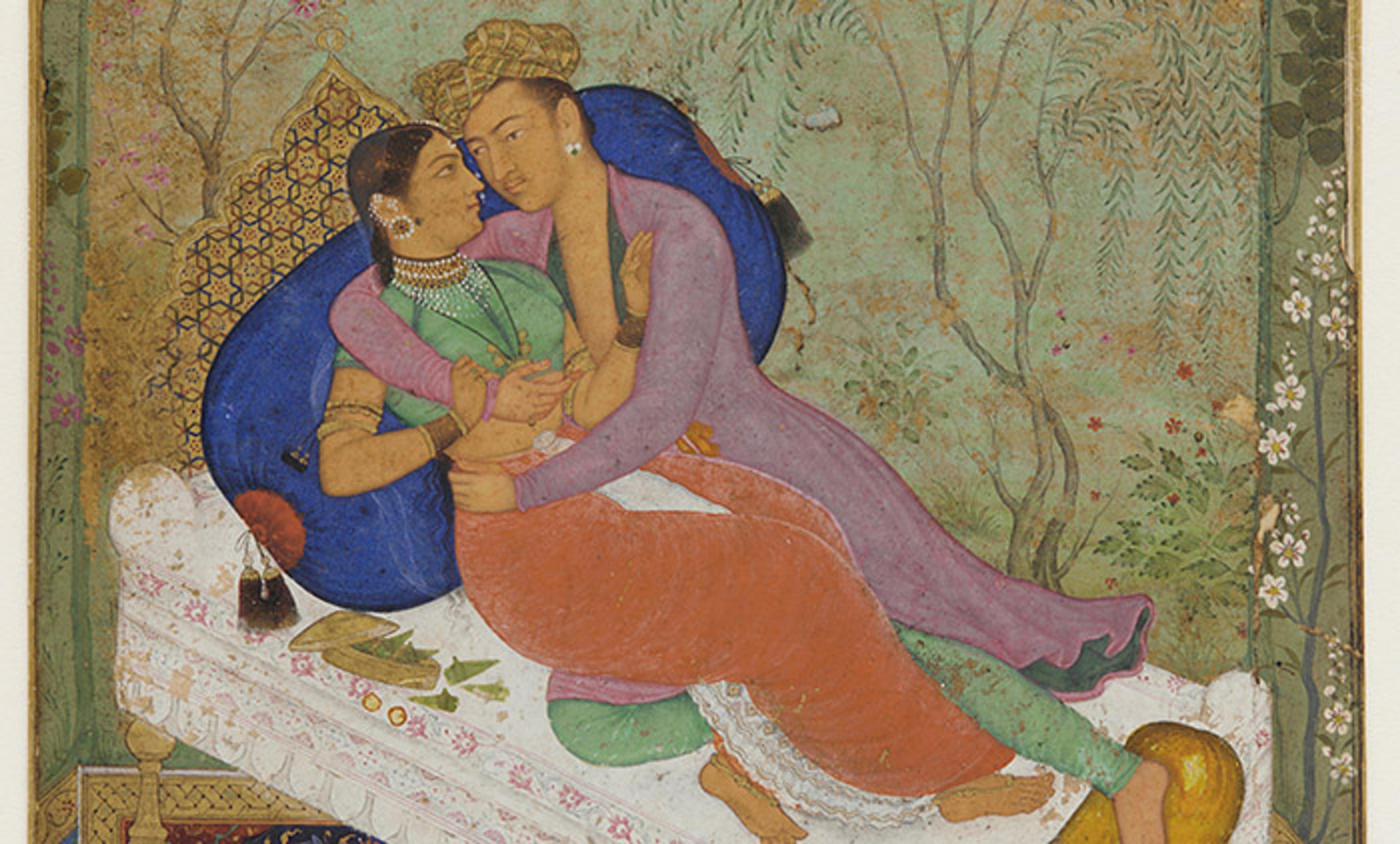

Lovers, Mughal dynasty c1597, attributed to Manohar. Courtesy Freer Gallery of Art/Wikipedia

‘The world has always belonged to males,’ wrote Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex (1949), ‘and none of the reasons given for this have ever seemed sufficient.’ Given the manifestly equal intelligence and capabilities of women, how could there have been so many centuries of sexual domination, of patriarchy? To many, the answers to this question have seemed as obvious as the privileges of power in any other form of social domination. As a result, critiques of patriarchy often take the shape of a struggle for power, a fight for control of the social agenda. However, as I see it, ‘social power’ explanations for institutions of sexual domination remain fundamentally flawed and insufficient.

In their place, I have proposed a historical dialectic that claims – and here I must be careful, lest the claim sound exculpatory – that such institutions of domination were inevitable, however wrong. I regard institutionalised sexual domination as an unavoidable part of a long, often painful, struggle to make sense of the reproduction of human life – resulting in the separation of sexual reproduction from sexual love, and the emergence of forms of life organised around bonds of sexual love.

In recent years, with astonishing rapidity, widespread social opposition to same-sex marriage has evaporated in many parts of the world. Reliable birth control, safe and legal access to abortion, and new kinship formations make the propagation of life and the raising of children seem less and less the result of sexual reproduction. At the same time, we are living through one of the most profound transformations in human history: the erosion of a gender-based division of labour. These developments do not just reflect newly discovered moral facts – ‘equality’ or ‘dignity’. Rather, I wish to suggest, they are the result of a long, collective effort at self-education, one that began by trying to make sense of what Genesis called ‘fruitfulness and multiplicity’.

At some point in the ancient past, human beings figured out that we reproduce sexually – that the reproduction of human life results from particular, significant acts for which we can hold one another accountable. The way we learned this must itself have been by attending to how or when we touch one another and engage one another sexually. Moreover, learning how we, as humans, reproduced must have also completely transformed the very ways in which we reproduce.

Once our ancestors understood not only that specific acts were potentially procreative but also that only certain individuals – at precise stages of life – were able to bear children, a socially significant division between the genders took hold, in the form of restrictions placed upon women. The patriarchal oppression of women, I suggest, stems not from any ‘will to dominate women’ (as de Beauvoir maintained) nor from the ‘arbitrary’ attribution of the gender woman to the female body (as Judith Butler has argued), but from our ancestors’ grasp of sexual reproduction.

Of course, much about sexual reproduction remained (and remains) mysterious: miscarriages, multiple births, the onset of pain. For a long time, the only aspect of sexual reproduction that was ‘known’ with confidence was the simple fact that only women of a certain age might bear children following particular sex acts with men. Among the consequences of this limited knowledge was an intensely pressing question: what are we doing with one another sexually when we are not procreating, or when sexual reproduction is known to be an impossible outcome of the sexual interaction?

This question has of course prompted enormous reflection, from Plato to Sigmund Freud. One haunting problem, however, deserves special scrutiny. In many circumstances, one essential aim of sex acts has been to prove that it’s not merely being wrung out of us – to disprove that sexual experiences are merely suffered or ‘undergone’, caused by natural appetite or procreative demands. Sexual experiences had to be understood – somehow – as expressive of an agent, as something we do as well as undergo.

Sadly, the certainty that one is acting sexually – not just driven by appetites or desires beyond one’s control – can be readily achieved through institutionalised sexual domination, by installing a gendered hierarchy of ‘active’ and ‘passive’ sexual roles. The mind boggles when considering the countless ‘initiations’, the deep and lasting ways in which human beings have lived this out – the systematic abuse of boys and girls, prostitution and sex trafficking, wives and concubines, socially sanctioned harassment and abuse – whereby the certainty of ‘acting sexually’ is achieved for some in the subjugation of others.

‘Sexual reproduction’ and ‘sexual domination’ remain, to this day, powerful ways to explain human sexual activity. Only when human beings began to understand themselves as sexual lovers – striving to understand and meet the demands of mutuality with each other – does the supremacy of those earlier explanations get challenged. Lovemaking, in other words, is a social-historical achievement – something realised in the erosion of the power of ‘sexual reproduction’ (biological necessity) and ‘sexual domination’ to explain what humans are doing with each other, sexually.

Two essential conditions for lovemaking – and forms of social life organised around bonds of sexual love – are the safe and legal availability of abortion and contraception. And, once fertile men and women can separate their sexual affairs from the claims of sexual reproduction, then ‘gender’ itself begins to falter as a basis on which we can conduct our love affairs. In light of the availability of abortion, contraception and new reproductive technologies – that is, thanks to the provisional liberation of sex from biological reproduction and gender-based divisions of labour – there is no longer any reason to regard love itself as gender-based. In our own time, these historical transformations have thus made possible the spreading acceptance of same-sex kinship and gender-indeterminate relationships.

Moreover, addressing the demands of mutuality has not just been the ‘private’ business of lovers, but of concrete social-institutional transformation: expanded marriage rights, anti-discrimination laws, the social accommodation of transgender individuals, and expanded rights for women, to name only a few. New prerogatives for the sexually subjugated, and new forms of kinship based on the authority of sexual love continue to emerge. As I see it, this means that our ways of treating or touching one another as lovers are not just expressions of how we already understand or value each other, or reflections of existing ‘power structures’. They are also ongoing attempts at understanding one another and our shared conditions – through immense and sometimes wrenching transformations in our values and commitments.