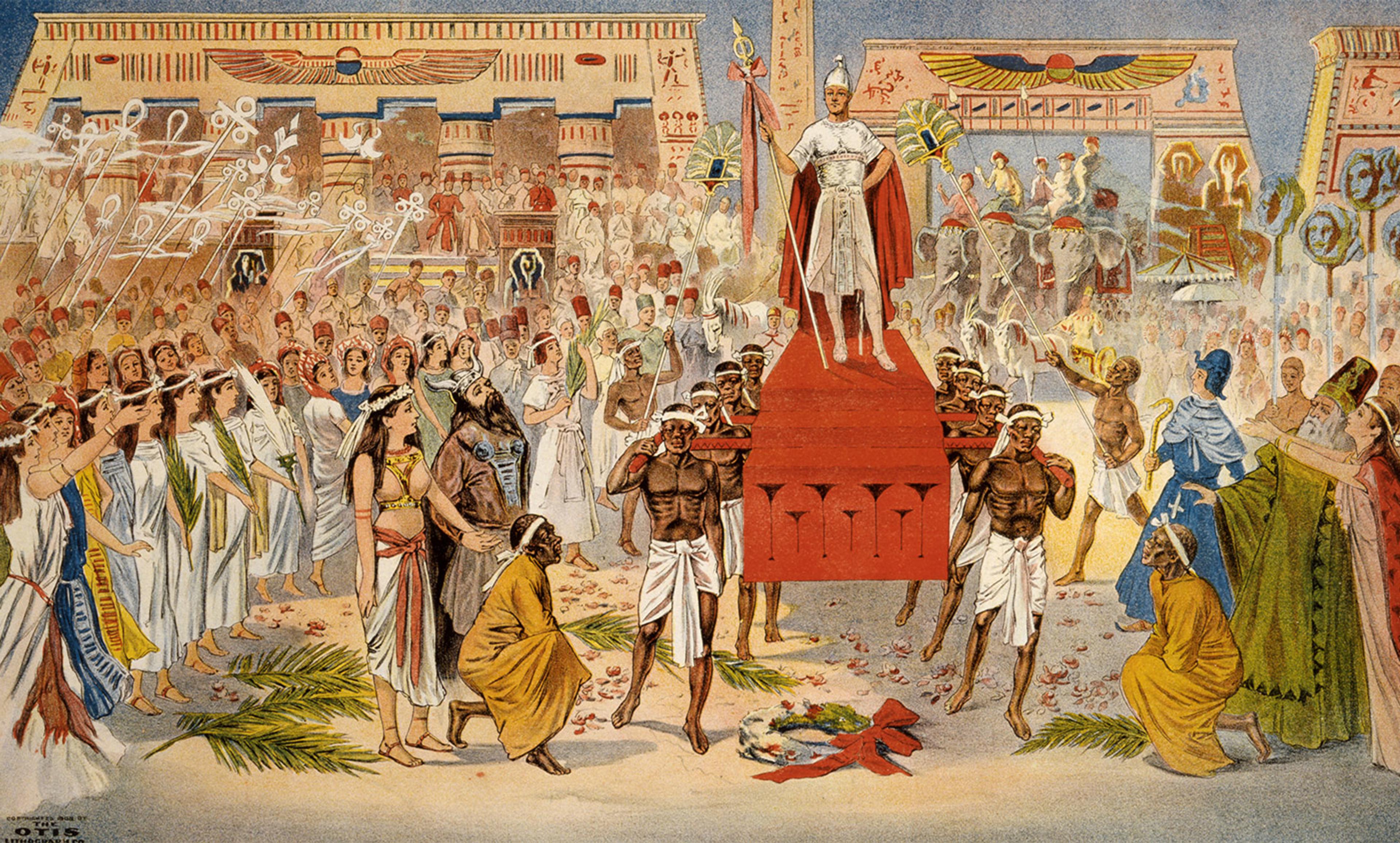

Flying Over Istanbul and the Galata Tower on the Magic Carpet from the 1001 Nights, Turkish miniature, 19th C. Photo by Rex

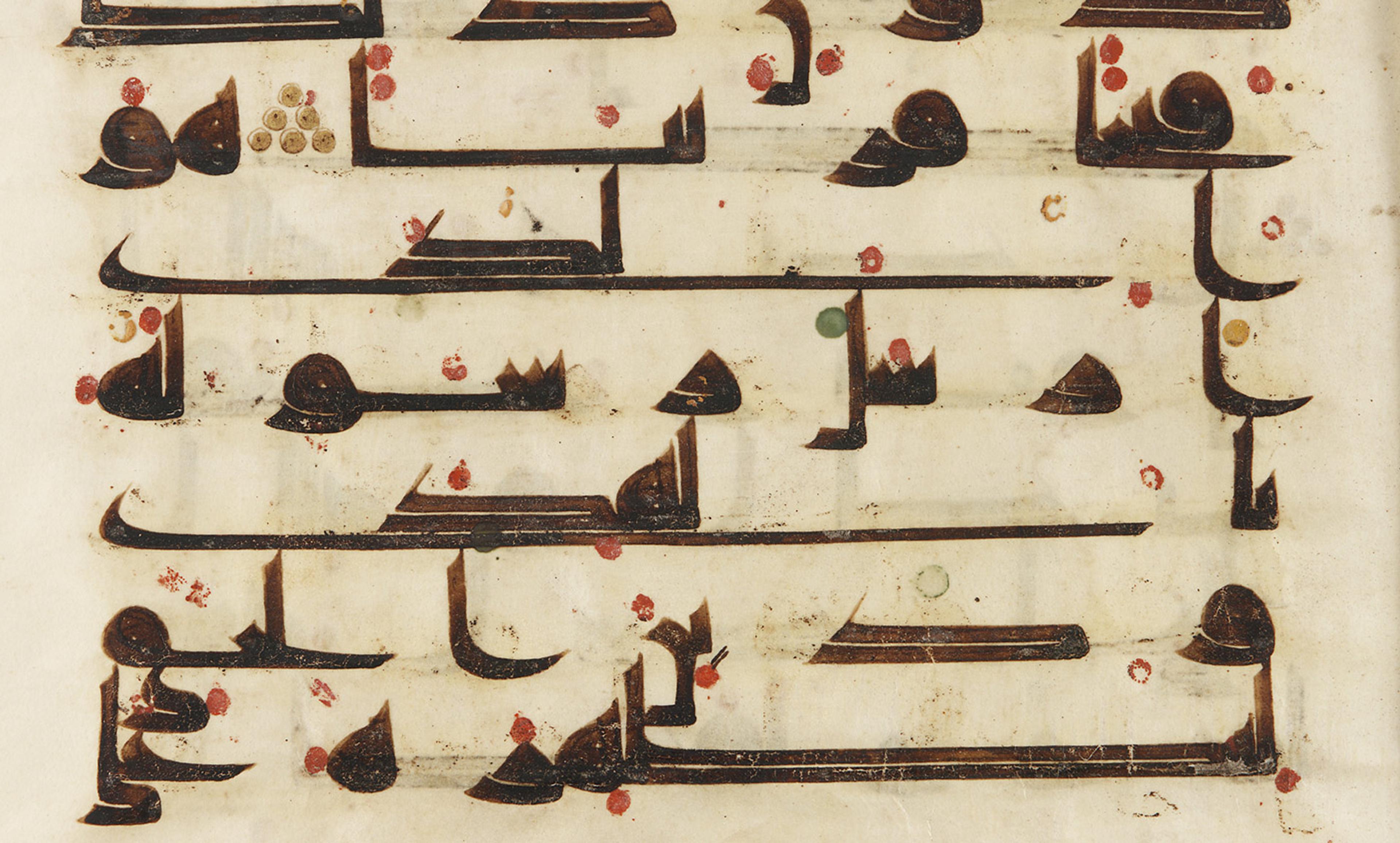

Think invisible men, time travel, flying machines and journeys to other planets are the product of the European or ‘Western’ imagination? Open One Thousand and One Nights – a collection of folk tales compiled during the Islamic Golden Age, from the 8th to the 13th centuries CE – and you will find it stuffed full of these narratives, and more.

Western readers often overlook the Muslim world’s speculative fiction. I use the term quite broadly, to capture any story that imagines the implications of real or imagined cultural or scientific advances. Some of the first forays into the genre were the utopias dreamt up during the cultural flowering of the Golden Age. As the Islamic empire expanded from the Arabian peninsula to capture territories spanning from Spain to India, literature addressed the problem of how to integrate such a vast array of cultures and people. The Virtuous City (al-Madina al-fadila), written in the 9th century by the scholar Al-Farabi, was one of the earliest great texts produced by the nascent Muslim civilisation. It was written under the influence of Plato’s Republic, and envisioned a perfect society ruled by Muslim philosophers – a template for governance in the Islamic world.

As well as political philosophy, debates about the value of reason were a hallmark of Muslim writing at this time. The first Arabic novel, The Self-Taught Philosopher (Hayy ibn Yaqzan, literally Alive, Son of Awake), was composed by Ibn Tufail, a Muslim physician from 12th-century Spain. The plot is a kind of Arabic Robinson Crusoe, and can be read as a thought experiment in how a rational being might learn about the universe with no outside influence. It concerns a lone child, raised by a gazelle on a remote island, who has no access to human culture or religion until he meets a human castaway. Many of the themes in the book – human nature, empiricism, the meaning of life, the role of the individual in society – echo the preoccupations of later Enlightenment-era philosophers, including John Locke and Immanuel Kant.

We also have the Muslim world to thank for one of the first works of feminist science fiction. The short story ‘Sultana’s Dream’ (1905) by Rokeya Sakhawat Hussain, a Bengali writer and activist, takes place in the mythical realm of Ladyland. Gender roles are reversed and the world is run by women, following a revolution in which women used their scientific prowess to overpower men. (Foolishly, the men had dismissed the women’s learning as a ‘sentimental nightmare’.) The world is much more peaceful and pleasant as a result. At one point, the visitor Sultana notices people giggling at her. Her guide explains:

‘The women say that you look very mannish.’

‘Mannish?’ said I, ‘What do they mean by that?’

‘They mean that you are shy and timid like men.’

Later, Sultana grows more curious about the gender imbalance:

‘Where are the men?’ I asked her.

‘In their proper places, where they ought to be.’

‘Pray let me know what you mean by “their proper places”.’

‘O, I see my mistake, you cannot know our customs, as you were never here before. We shut our men indoors.’

By the early 20th century, speculative fiction from the Muslim world emerged as a form of resistance to the forces of Western colonialism. For example, Muhammadu Bello Kagara, a Nigerian Hausa author, wrote Ganďoki (1934), a novel set in an alternative West Africa; in the story, the natives are involved in a struggle against British colonialism, but in a world populated by jinns and other mystical creatures. In the following decades, as Western empires began to crumble, the theme of political utopia was often laced with a certain political cynicism. The Moroccan author Muhammad Aziz Lahbabi’s novel The Elixir of Life (Iksir al-Hayat) (1974), for example, centres on the discovery of an elixir that can bestow immortality. But instead of filling society with hope and joy, it foments class divisions, riots, and the unravelling of the social fabric.

An even darker brand of fiction has emerged from Muslim cultures today. Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad (2013) reimagines Frankenstein in modern-day Iraq, among the fallout from the 2001 invasion. In this retelling, the monster is created from body parts of different people who have died because of ethnic and religious violence – and eventually goes on a rampage of its own. In the process, the novel becomes an exploration of the senselessness of war and the deaths of innocent bystanders.

In the United Arab Emirates, Noura Al Noman’s young adult novel Ajwan (2012) follows the journey of a young, amphibious alien as she fights to recapture her kidnapped son; the book is being made into a TV series, and touches on themes including refugees and political indoctrination. In Saudi Arabia, Ibraheem Abbas and Yasser Bahjatt’s debut science-fiction novel HWJN (2013) explores gender relations, religious bigotry and ignorance, and offers a naturalistic explanation for the existence of jinns who reside in a parallel dimension. The Egyptian writer Ahmad Towfiq’s bleak novel Utopia (2008), meanwhile, envisions a gated community in 2023, where the cream of Egyptian society has retreated after the country’s wholesale economic and social collapse. And in post-Arab Spring Egypt, the novelist Basma Abdel Aziz conjures a Kafkaesque world in The Queue (2016) – a book set in the aftermath of an unsuccessful uprising, in which helpless citizens struggle to get by under the thumb of an absurd and sinister dictatorship.

Speculative fiction is often lumped in with European Romanticism and read as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. But if this gallop through the centuries of Muslim endeavour shows anything, it’s that pondering fantastical technologies, imagining utopian social arrangements, and charting the blurry boundaries between mind, machine and animal, are not the sole preserve of the West.