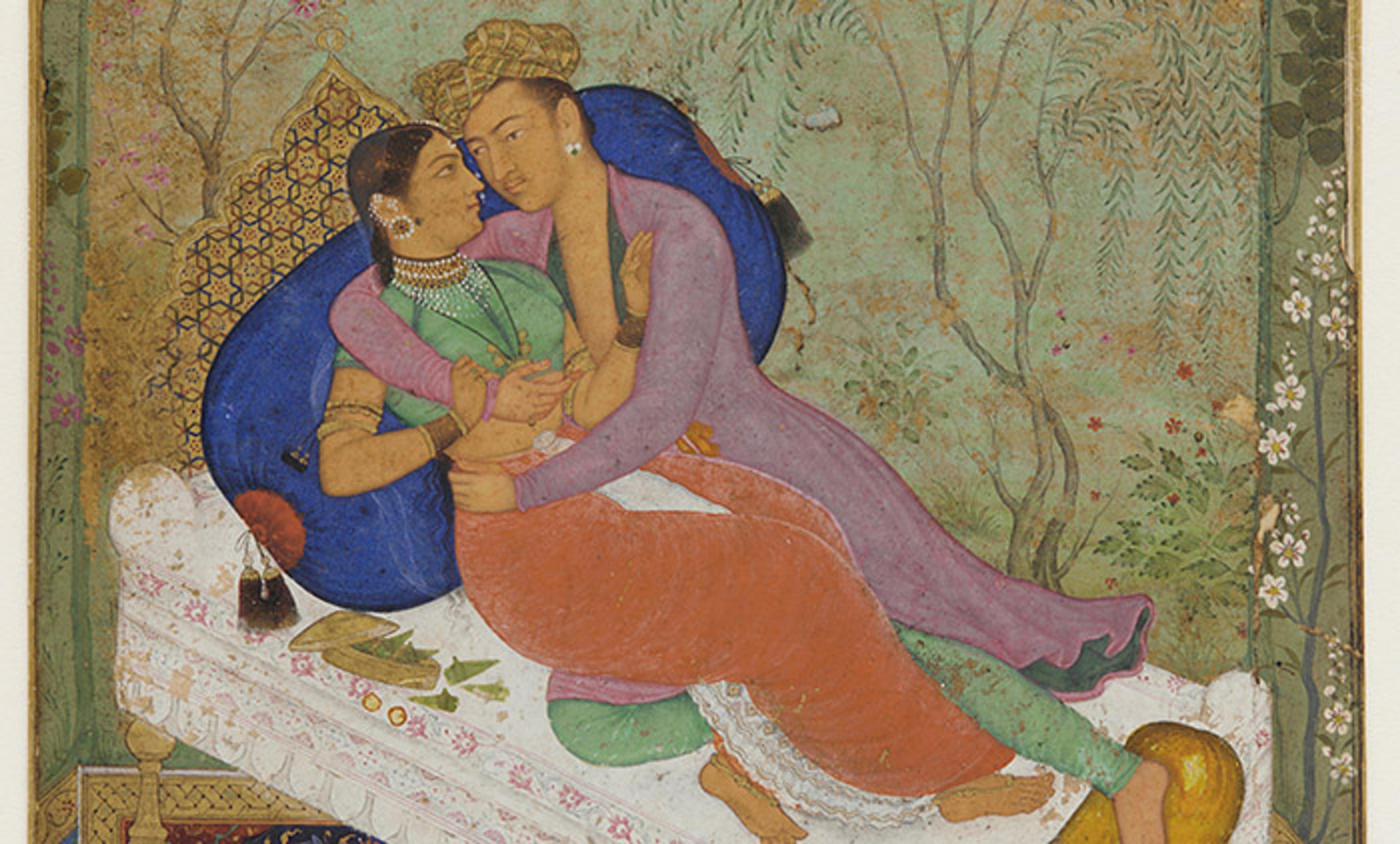

Erotic scene (1743) ascribed to Abdullah Bukhari, Turkey, probably Istanbul. Photo courtesy Sothebys

History might be the best antidote to the unthinking, and pernicious, naturalisation of cisgender identity and heterosexuality. When confronted with the fact that, for most of history, people simply did not conceive of human sexuality in fixed and dimorphic terms, it becomes much easier to imagine a liberating, pluralist future.

In ancient Greece, the semi-institutionalised relationships between erastês and erômenos (ie, adult men and young boys) offer an example of sexual mores that differ from those of the present. When scholars say that ‘homosexuality’ is a modern construct, they do not, of course, mean that people in the past did not engage in same-sex romantic or erotic relations. They mean, rather, that same-sex relations were viewed in pre-modern times as merely a predilection or practice, whereas during the 19th century they came to be considered an innate nature, an identity.

The German term Homosexualität was coined only around 1868 by the Austro-Hungarian author and journalist Károly Mária Kertbeny (formerly Karl-Maria Benkert). This fact raises the question of how people might have conceptualised what we now think of as homosexuality before the word existed. This is why, as Robert Beachy has suggested, we should speak instead of the ‘invention’ of homosexuality in late 19th-century Europe. In this context, the title of intellectual historian Khaled el-Rouayheb’s book on same-sex relations avant la lettre is significant – Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500-1800 (2005).

In the Ottoman Empire, prior to the advent of Western-influenced heteronormativity in the late-19th century, sexual mores presented a very different picture. A closer look at the Ottoman experience of sexuality is instructive. With the Ottomanists Helga Anetshofer and İpek Hüner-Cora at the University of Chicago, I have been combing through five centuries of Ottoman literary works searching for sexual terminology. The results of this research – currently more than 600 words – teach us, if not necessarily how people actually lived, then at the very least how they thought about sex throughout the Ottoman-speaking world, principally the territory of modern Turkey and its immediate neighbours.

Although there is no doubt that the vocabulary extracted thus far is not exhaustive, some clear patterns have emerged. In particular, it indicates that one can speak of three genders and two sexualities. First, rather than a male/female dichotomy, sources clearly view men, women and boys as three distinct genders. Indeed, boys are not deemed ‘feminine’, nor are they mere substitutes for women; while they do share certain characteristics with them, such as the absence of facial hair, boys are clearly considered a separate gender. Furthermore, since they grow up to be men, gender is fluid and, in a sense, every adult man is ‘transgender’, having once been a boy.

Second, sources suggest that there are two distinct sexualities. But rather than a hetero/homosexual dichotomy, the two sexualities are defined by penetrating and being penetrated. For a man who penetrates, whom he penetrates was considered to be of little consequence and primarily a matter of personal taste. It is indeed significant that the words used for an ‘active’ man’s sexual orientation were quite devoid of value judgment: for example, matlab (demands, wishes, desires), meşreb (temperament, character, disposition), mezheb (manner, mode of conduct, sect), tarîk (path, way, method, manner), and tercîh (choice, preference). Being objects of penetration, boys and women were considered not quite as noble as men. As sexual partners, however, neither women nor boys were held to be more estimable than the other. In short, instead of a well-defined sexual identity, literature suggests that, in Ottoman society, a man’s choice of sexual partner was viewed purely as a matter of taste, not unlike a person today might prefer wine over beer or vice versa.

El-Rouayheb has shown that the assessment of many Western Orientalists concerning the ostensible prominence and acceptance of homosexuality in the Middle East and North Africa has been anachronistic, suffering from the presentist presumption of the universal and transhistorical validity of a unitary notion of homosexuality. He has argued that pre- and early modern Arabic sources suggest the existence of a more nuanced, role- and age-differentiated view of same-sex relations. As Frédéric Lagrange, a scholar of Arabic literature at the Sorbonne in Paris, has put it in Islamicate Sexualities (2008): ‘the contemporary Western reader who has never perhaps questioned his holistic conception of homosexuality finds it “sliced up” into a multitude of role specialisations, since medieval authors usually see no “community of desire” between, for instance, the active and the passive partners of homosexual intercourse.’

The sexual terminology used in Ottoman-era literature suggests that precisely the same held in that case as well: ‘homosexuality’ as an all-embracing term covering partners male as well as female, young as well as old, active as well as passive simply did not exist. Instead, the Ottoman language is extremely rich in highly specialised words that describe specific participants fulfilling specific roles.

By the late-19th century, relations between men and boys had fallen into disfavour. In a much-quoted document submitted to Abdülhamid II, sultan from 1876 to 1909, the historian and statesman Ahmed Cevdet Pasha wrote:

Woman-lovers have increased in number, while boy-beloveds have decreased. It is as if the People of Lot have been swallowed by the earth. The love and affinity that were, in Istanbul, notoriously and customarily directed towards young men have now been redirected towards girls, in accordance with the state of nature.

The decline in pederasty was, of course, salutary. However, the change also heralded the advent of Western-influenced heteronormativity in Ottoman society, and of the repression it inevitably entails.

Homophobia is a powerful force in Turkey today. On 26 May 1996, a week before the Second United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) held in Istanbul, a Right-wing mob staged a pogrom against cross-dressers and transgender people living on Ülker Street near Taksim Square, resulting in deaths and injuries as well as their eviction from their homes. Last year, the authorities prevented Istanbul’s annual Gay Pride parade from taking place after a band of troglodytes threatened to disrupt it.

One can only hope that the Turkish government’s much-flaunted veneration of its Ottoman ancestry will, one day, also extend to a more enlightened approach to sexuality.