At the Tehran Book Fair. Photo by Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu Agency/Getty

There is a conundrum facing Iranian officials. The government, on the one hand, wants Iranians to read more. At the same time, with the other hand, it wants to cover their eyes.

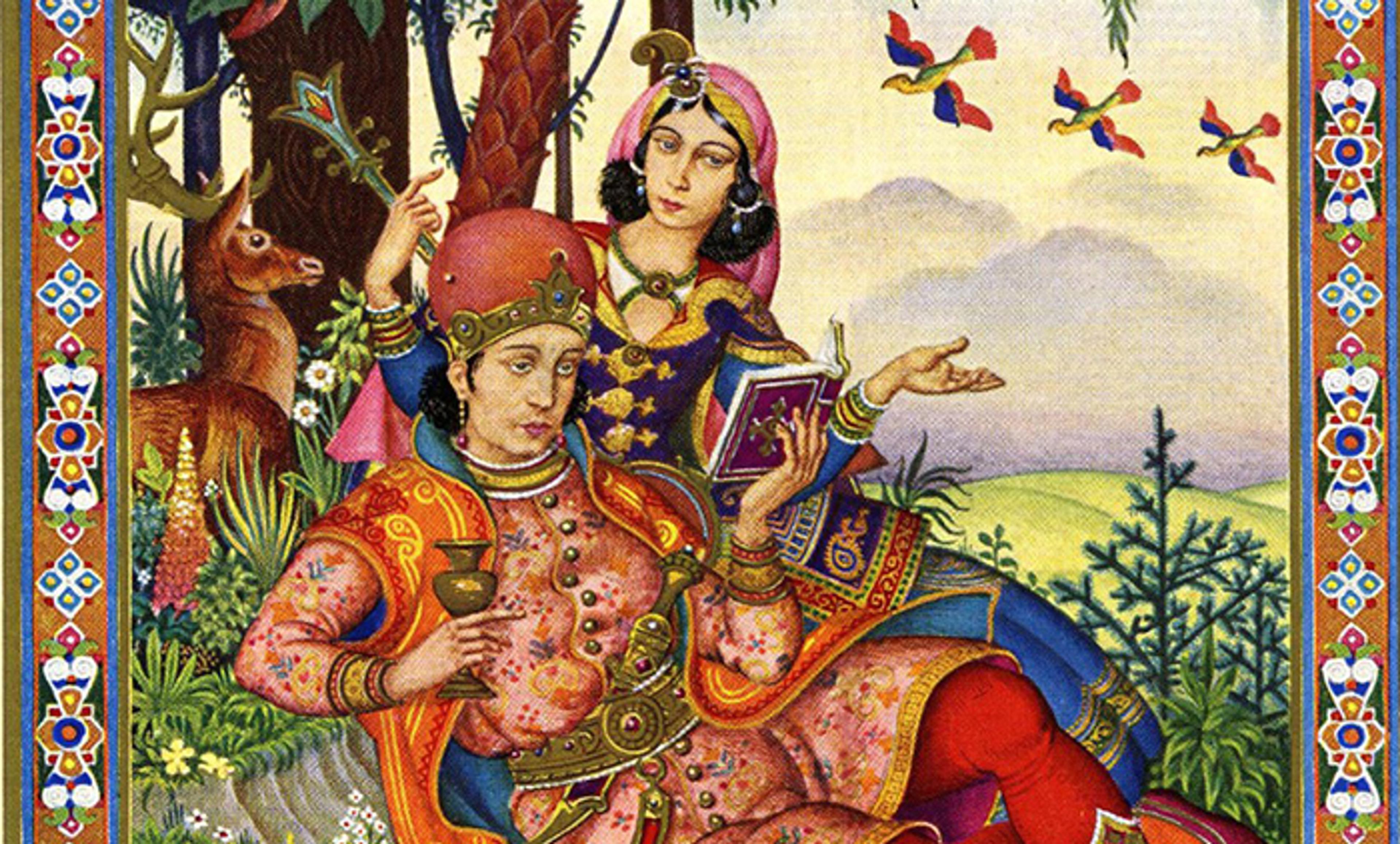

Love of the written word is deeply rooted in Iranian society, due to its extraordinary history of arts, sciences and literature. However, Iranians aren’t reading enough. Bookstores in Iran are a rarity, with some 1,500 shops for a population of almost 80 million. There was a time when publishers gave books a print run of 3,300-5,500 copies. Now, the numbers have dropped drastically to 500, sometimes even 300 copies.

That’s why the Iranian government recently announced it would be opening the largest bookstore in the world – by square footage – during the coming months. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, this title was held by the Barnes & Noble bookstore in New York City, which covered 154,250ft². Unfortunately, the 5th Avenue flagship store closed down in 2014.

Mahamoud Salahi, the head of the Art and Cultural Organization of Tehran Municipality, announced that Bagh-e-Ketab (the Book Orchard/Garden) will be 484,376ft² (45,000m²), triple the size of the once world-record holder. This bookstore is expected to cater to all walks of life and ages, but will focus on youth and include an auditorium for theatre performances, and four research departments for university professors to hold workshops and study sessions. The Tehran municipality has reportedly already spent 100 billion rials (more than $3 million) on the project.

‘Currently, we are at a stage of getting the store’s equipment. We hope that all interested publishers will be able to place their work on our shelves,’ Salahi told Iranian reporters. During 2015, he pushed for a campaign to promote reading by distributing free books and booklets on buses and subways for people. This had existed previously, but was halted three years prior, for reasons unknown.

Salahi isn’t alone in encouraging people to read. An Iranian taxi driver in the city of Rasht recently decided to turn his car into a mobile library in hopes of garnering new love for the written word. But will such efforts do any good?

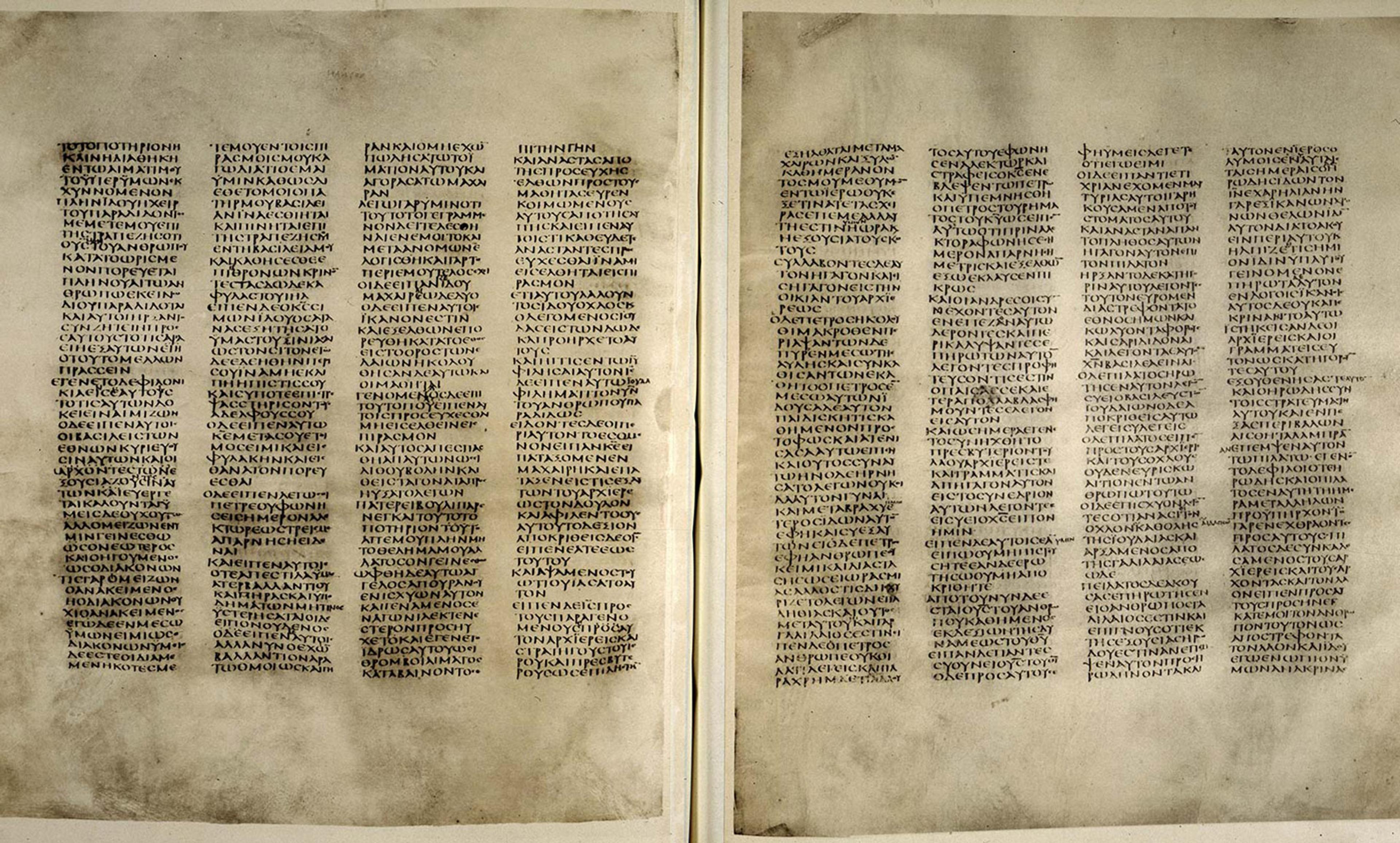

Much of the reason for Iranians’ lack of interest in reading printed books has to do with censorship. Iran is ranked as one of the top 10 censored countries in the world. When it comes to publishing, the process is very meticulous: it can take months, sometimes years, to pass a book through the country’s Kafkaesque bureaucracy. Books must first be submitted to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to be reviewed by at least one anonymous censor, whose job is to make sure the text follow the rules and regulations of the Islamic Republic – albeit through the censor’s interpretations of the law. The censor’s work is described in Persian as momayezi, a polite word for ‘evaluating’. The process is intricate and usually relies on the use of the ‘Ctrl+F’ approach to find specific words and phrases that might be deemed anti-Islamic, against Iranian security or immoral. For example, the kissing and dancing scenes, as well as any mention of alcohol, are changed in the Persian translation of the Harry Potter series. Sometimes, entire chapters are removed, and certain books never make into print.

In January, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance added new regulations to censorship, which included a ban on the names of foreign animals, certain foreign leaders, and synonyms for ‘wine’. In short, anything that the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei describes as a ‘Western cultural invasion of Iran that seeks to destroy Islamic identity’.

Since the coming of the pragmatist president Hassan Rouhani in 2013, many improvements have been made in the cultural sphere – in film, literature and theatre. Bans on certain books and films have since been lifted, including on Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not (1937), Marguerite Duras’s The Lorry (1977), José Saramago’s Blindness (1995), and Tracy Chevalier’s Girl With a Pearl Earring (1999).

Still, even at the annual Tehran International Book Fair – which over 10 days garners the attention of some 500,000 Iranians daily – there are issues. Although the fair is called ‘international’, there are few foreign titles and publishers, especially Western ones. Last year, authorities removed 10 books and shut down 29 booths and for ‘presenting and selling books by other publishers’.

To fight censorship, authors and readers at home and abroad are uploading banned books to the internet, where Iranians download them for free. Iraj Pezeshkzad’s classic coming-of-age novel My Uncle Napoleon (1973) and Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl (1937) are readily available online, together with countless other banned Western titles translated into Persian. This includes Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion (2006) and The Blind Watchmaker (1986) as well as The Satanic Verses (1988) by Salman Rushdie – the very book that caused Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran’s revolution in 1979, to issue a death fatwa for the author, which is still in place today.

Iranians have also come up with online publishing houses to bring out writer’s works as ebooks, either from their own websites or via apps such as Google Books. The Iran-based Nogaam has published 25 books since 2013, mostly by authors who reside in the country and would otherwise have no chance of being published due to censorship. Books are crowdfunded, and once writers are compensated for their work, the titles become available for free download. Other companies such as Fidibo serve as digital libraries that feature ebooks with publishing permission from the Iranian government.

It seems that, whether Iran likes it or not, the Iranian people are moving towards ebooks, much like the rest of the world. Still, that hasn’t prevented banned books from being smuggled in from Afghanistan, where there are no restrictions on publication. Iranians also rely on travelling friends and family for contraband books brought back hidden in suitcases. At least, that’s how I got my original copies in English of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and the Harry Potter series.