Maelick/Flickr

I’m having dinner with my flatmates when my friend Morgan takes a picture of the scene. Then she sits back down and does something strange: she cocks her head sideways, crosses her eyes, and aims the phone at herself. Snap. Whenever I see someone taking a selfie, I get an awkward feeling of seeing something not meant to be seen, somewhere between opening the unlocked door of an occupied toilet and watching the blooper reel of a heavy-handed drama. It’s like peeking at the private preparation for a public performance.

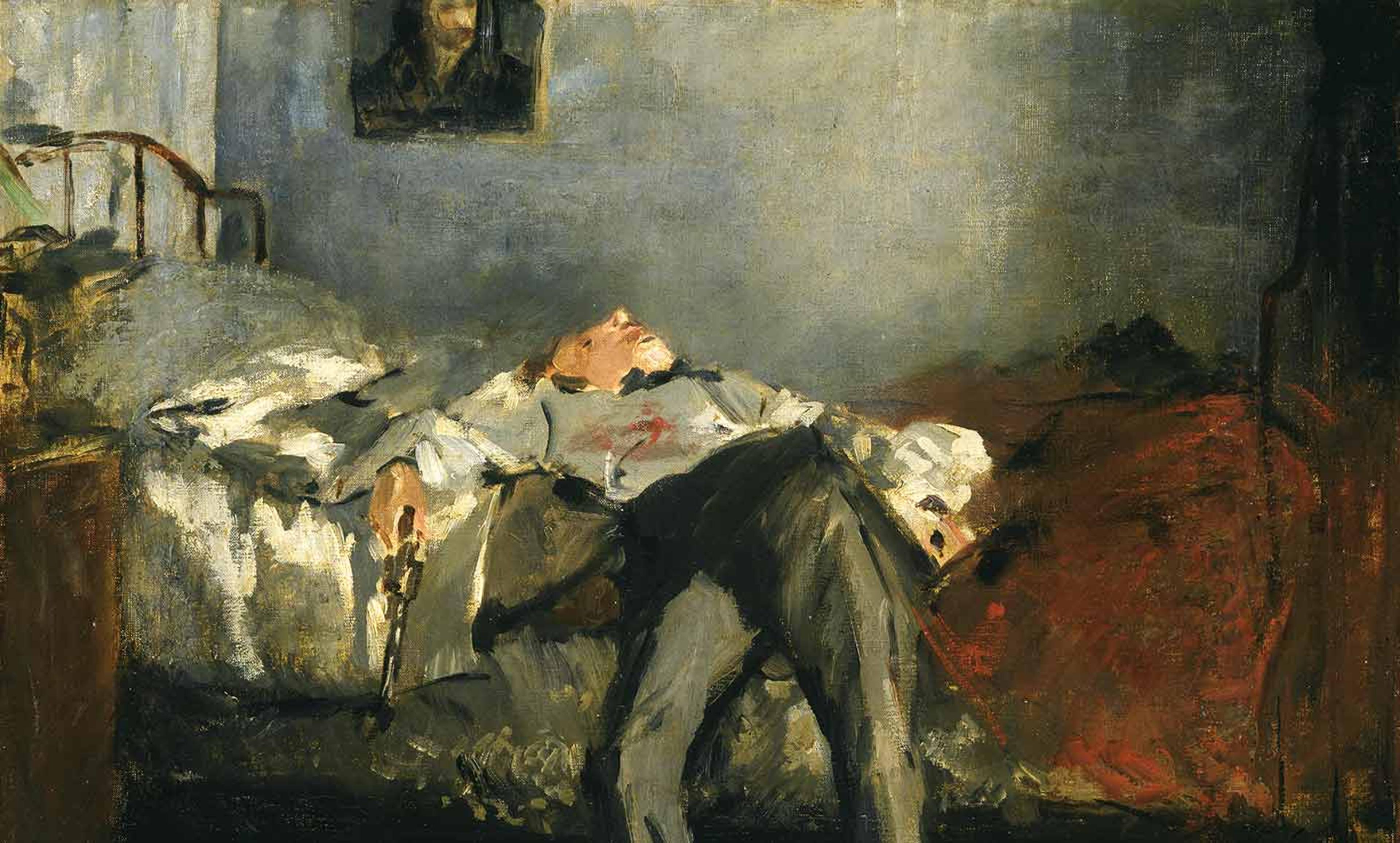

In his film The Phantom of Liberty (1974), the director Luis Buñuel imagines a world where what should and shouldn’t be seen are inverted. In a ‘dinner party’, you shit in public around a table with your friends, but eat by yourself in a little room. The suggestion is that the difference between the public and the private might not be what you do but where you do it, and to what end. What we do in private is preparing for what we’ll do in public, so the former happens backstage whereas the latter plays out onstage.

Why do we so often feel compelled to ‘perform’ for an audience? The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre suggests that narrating is a basic human need, not only to tell the tale of our lives but indeed to live them. When deciding how to read the news, for example, if I’m a millennial I follow current events on Facebook, and if I’m a banker I buy the Financial Times. But if the millennial buys the Financial Times and the banker contents himself with Facebook, then it seems the roles aren’t being played appropriately. We understand ourselves and others in terms of the characters we are and the stories we’re in. ‘The unity of a human life is the unity of a narrative quest,’ writes MacIntyre in After Virtue (1981). We live by putting together a coherent narrative for others to understand. We are characters that design themselves, living in stories that are always being read by others. In this light, Morgan’s selfie is a sentence in the narration that makes up her life.

Similarly, in Nausea (1938) Jean-Paul Sartre wrote: ‘a man is always a teller of stories, he lives surrounded by his stories and the stories of others, he sees everything that happens to him in terms of these stories and he tries to live his life as if he were recounting it’. Pics or it didn’t happen. But then he must have asked himself, sitting at the Café de Flore: Am I really going to tell someone about this cup of coffee I’m drinking now? Do I really recount everything I do, and do everything just to recount it? ‘You have to choose,’ he concluded, ‘to live or to tell.’ Either enjoy the coffee or post it to Instagram.

The philosopher Bernard Williams has the same worry about the idea of the narrated life. Whereas MacIntyre thinks the unity of real life is modelled after that of fictional life, Williams argues that the key difference between literature’s fictional characters and the ‘real characters’ that we actually are resides in the fact that fictional lives are complete from the outset whereas ours aren’t. In other words, fictional characters don’t have to decide their future. So, says Williams, MacIntyre forgets that, though we understand life backwards, we have to live it forwards. When confronted with a choice, we don’t stop to deliberate what outcome would best suit the narrative coherence of our stories. True: sometimes, we can think about what decision to make by considering the lifestyle we have led, but for that lifestyle to have come about in the first place we must have begun to live according to reasons more fundamental than the concerns of our public image. In fact, says Williams, living by reference to our ‘character’ would result in an inauthentic style different from that which had originally risen, just like when you try methodically to do something that you’ve always done naturally – it makes it harder. If you think about how to walk when you’re walking, you’ll end up tripping.

When Williams wrote this more than 10 years ago, there were fewer than half the selfies in the world than there are today. If he’s right, does that mean we’re trying to understand more about ourselves now? In a way, it does, but that’s because making sense of our lives backwards is actually necessary to carry them forwards. As the philosopher David Velleman says, human beings construct a public figure in order to make sense of their lives, not as a narration but as a readable image that they themselves can interpret as a subject with agency. Even Robinson Crusoe, isolated from any audience, would need to shape a presentation of himself so that he could keep track of his life. From this need for intelligibility stems the distinction between the private and the public spheres: in order to be intelligible, we must construct a self-presentation, and in order to do that we must select what of our lives we present and what we choose to keep private. So the private sphere is what we hide not because we deem it shameful but because we decide it doesn’t contribute to our self-presentation, and hence to our sense of agency. Morgan’s selfie, here, is just a manifestation of the basic human need for self-presentation.

The selfie epidemic, Velleman might say, is a consequence of the increase in the amount of tools for self-presentation – Facebook, Twitter and the like. That, taken together, shrinks the private sphere. If controlling what we show is an inevitable urge, social media is only an explosion of the means to satisfy it. On the face of this, Velleman thinks we could use a little more refraining, but he wrote this 14 years ago. Today, I imagine him ranting at the hashtags that colour people’s self-presentation (#wokeuplikethis, #instamood, #life, #me). But no matter: he himself said that everyone is entitled to expose and hide whatever they see fit.

Whether life should be seen as a narrative or not, living is about choosing what to present and what to keep to oneself. We must navigate between the two. And if what counts as public or private can vary among cultures or age groups, it can vary among individuals too, so whenever I catch my flatmates snapping a selfie, I will continue to feel just as awkward as if I’d accidentally caught them changing their underwear.

A version of this piece was published in the Spanish language magazine Nexos.