Adapted from a post at BLDGBLOG, this short animation is an Aeon original made in collaboration with the filmmaker and animator Flora Lichtman.

There are many ways of moving through the Universe – of travelling from one point to another over great, even extraordinary distances. There is also a way of using the world for your own ends: taking advantage of slopes, winds, currents or gravitational fields, as fuel-efficient resources for your own acceleration.

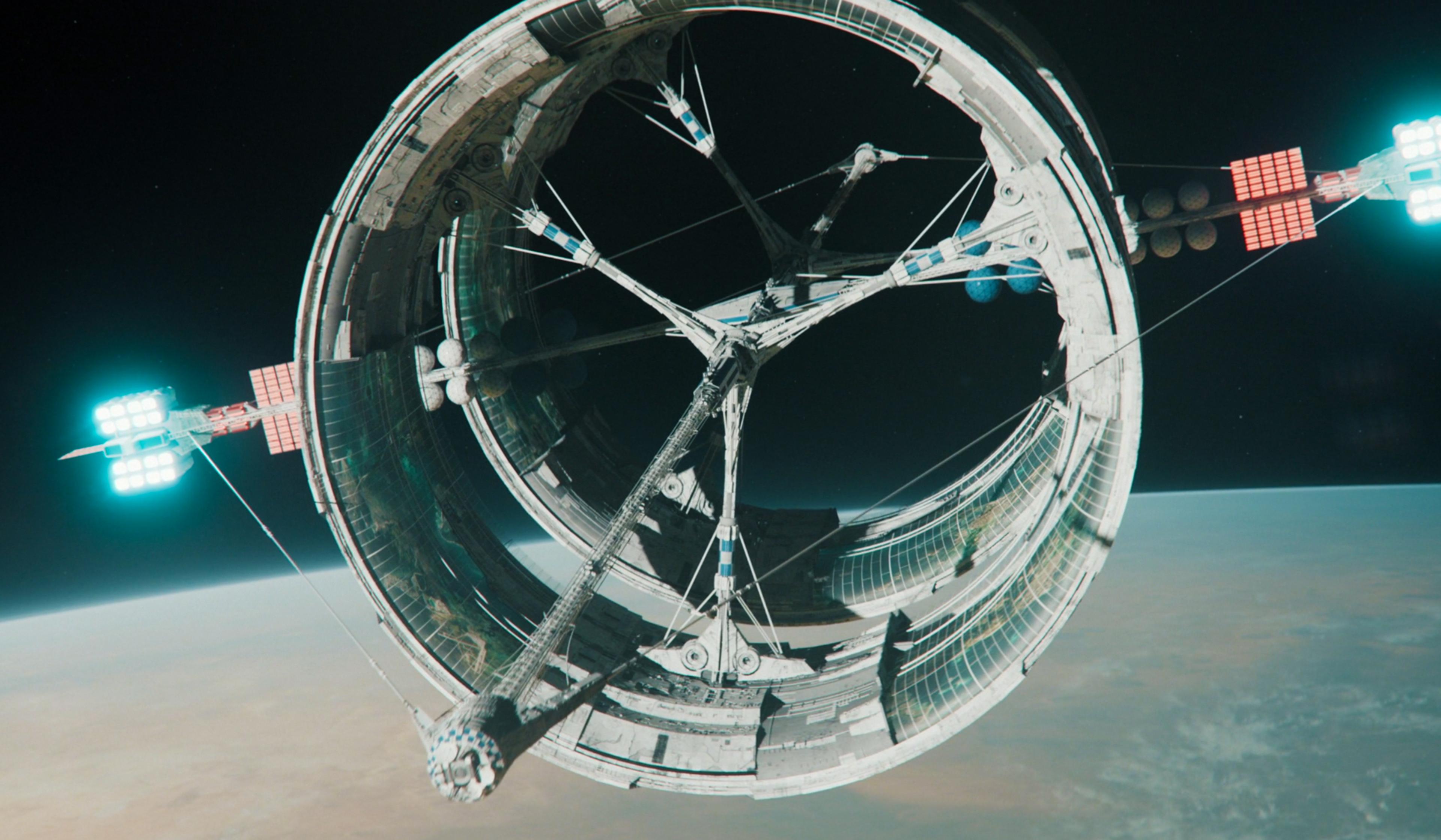

Gravity-assisted space travel is one such example, when a spacecraft uses the gravitational pull of a nearby planet or other celestial body to ‘slingshot’ itself toward another, more distant goal. Crucially, the target or destination here is one that could not have been reached without this assistance, not only in terms of the ship’s velocity but even in terms of its original direction of travel.

You head toward one place to get to another – or, channelling Hamlet, ‘by indirections find directions out’.

Remarkably, this metaphorically rich idea of heading in one direction to arrive somewhere else entirely connects gravitational slingshots with the oceangoing people who settled remote island chains in the South Pacific. These ancient mariners learned to use a combination of seasonal winds and celestial navigation to push ever farther east, reaching the most extreme outer edges of Polynesia.

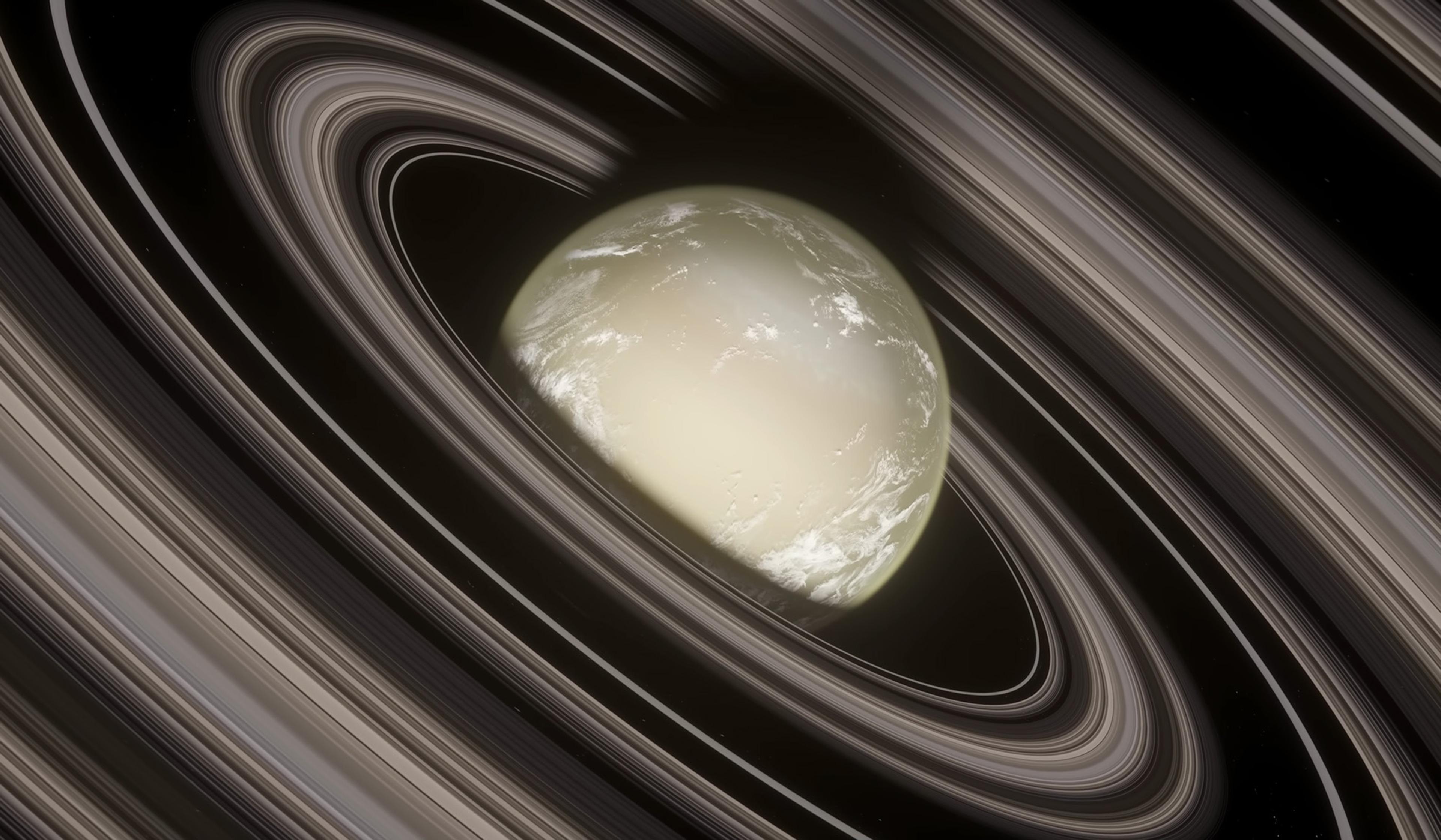

Early human settlement of the offshore Pacific revolved, in part, around enduring, large-scale meteorological phenomena that are still little understood. Most of these phenomena relied on what the maritime historian Brian Fagan called ‘an elaborate, usually slow-moving waltz involving two partners – the atmosphere and the ocean’. The local seasonal winds, combined with large but predictable long-term climatological events the size of continents, could be used to propel people from one archipelago to another.

We can draw a rough analogy between this climatologically assisted exploration of the remote outer Pacific and the careful interplanetary techniques of gravity-assisted space travel. Imagine, for example, a well-organised group of extreme maritime navigators standing on the shores of an isolated Pacific island chain 1,000 years ago, looking much further out to sea, knowing that there are distant land masses there, ever more island worlds whose presence is implied by the behaviour of the winds, clouds and currents.

More important, from generations’ worth of experience navigating the vast and inhospitable space of the Pacific, these same families know that only a particularly strong atmospheric cycle will be able to take them there – and that they must wait another season, another year, another decade, for these assistive winds to arrive. They are timing their launch.

Like NASA scientists calculating the positions of Mars and Jupiter as they hope to slingshot themselves beyond the black horizon of the solar system, these navigators would have known that the regional winds also move in cycles, or perhaps even that an unpredictable 100-year superstorm will be required to bring them further out into the ocean.

Awaiting these alignments, they temporarily become land-based, settling on a particular island and raising their children on the atmospheric folklore of a journey yet to come – telling themselves a science fiction not of interplanetary travel, but a kind of anthropological Star Trek of outer-sea exploration. Then, of course, the winds pick up – or ominous Antarctic clouds begin to appear on the southern horizon again for the first time in a generation – and everyone knows what these signs really mean. The skies are clicking back into place and, spurred on by this vast meteorological clock, they begin to build new canoes, their own wooden space probes for pushing the limits of a maritime universe.

It’s simply a different kind of sling-shotting: not between planets using gravity, but from island chain to island chain, riding a long tail of Pacific winds you know won’t last, and that only appear once per generation. Future storms will take you to distant archipelagoes where your descendants will then have to wait another year – another decade, another century – memorising the climate and plotting their woven way through the ‘slow-moving waltz’ of the world’s rhythmic winds and currents.

– Geoff Manaugh