In 1970, Allen Jones exhibited Hatstand, Table, and Chair: three sculptures of women wearing fetish clothing, posed as pieces of furniture. The sculptures were met with protests and stink-bomb attacks, particularly from feminists, who argued that the works objectified women. Despite the artist’s intentions for this piece – he has since identified as a feminist – the installation became part of an artistic narrative that has, historically, reduced women to passive objects in painting and sculpture.

In 2014, Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B (2012) was shut down at the Barbican in London after protests caused ‘security concerns’. The installation, based on 19th- and early 20th-century ‘human zoos’, showed Black people on display, chained and restrained. Even though the artist – a white South African man – intended the work to expose historic racist and imperialist violence, protesters implored the gallery to censor it: ‘Caged Black People Is Not Art’ read one banner.

And in 2019, an exhibition of Gauguin’s portraits opened at the National Gallery in London with a public debate to address ethical concerns about the artist and his work. Paul Gauguin was a sexual predator, and when in the South Pacific – where he created some of his best-known paintings – he used his colonial and patriarchal privilege to sexually abuse girls as young as 13, knowingly infecting them with syphilis. Indeed, many of us struggle to reconcile an artist’s appalling behaviour with their art: Pablo Picasso was, like Gaugin, a sexual predator, and a misogynist; Leni Riefenstahl was a Nazi and exploited Romani people in her filmmaking; and the sculptor Eric Gill was a paedophile. Often, we can sense the artist’s moral character in their works: Picasso’s views about women, for example, can be detected in many of his late portraits due to his manner of depiction.

These cases, among many more, show that, far from being innocuous objects hidden away in museums and white cubes, artworks are historically informed objects that do things and say things. Artworks are created by people in particular times, responding to specific events and ideals. In The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981), the philosopher Arthur Danto observed this with his thought experiment: a series of indiscernible red canvases could conceivably constitute completely different artworks, depending on their title, context of presentation, and so on. There is more to a painting or sculpture than its aesthetic forms of colour, line and shape. External properties, such as the artist’s identity and relevant events during the work’s creation, must be considered to fully understand the work. Just how much the artist’s intentions for their art determine that artwork’s meaning is a deep question – one that I can’t answer here. But, in general, most philosophers agree that an artwork can admit of many interpretations, and its meaning often diverges from what the artist intended. Crucially, artworks are communicative objects, the messages of which are partly determined by the surrounding context and are sometimes different to what the artist had in mind.

In particular, artworks can express sentiments, including moral ones, through their contextual and visual handling of subject matter. Note how the composition of Titian’s Rape of Europa (1559-62) – painted in a time when sexual violence was often eroticised in art – blurs the lines between refusal and consent. The depicted abduction before the impending sex shows Europa in a precarious – non-consensual – posture. Her erogenous zones are foregrounded, and the event is surrounded with sensuous textures: soft flesh, wet clothing, frothing foam. As the philosopher A W Eaton argues, this painting eroticises the rape it depicts, glamorising an uneven power dynamic that peddles the myth that rape is erotically charged. Indeed, Titian intended his painting to be erotic, outlining in a letter his goal for it to have erotic appeal for the male viewer.

The Rape of Europa (c1559-62) by Titian. Courtesy the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Relatedly, it’s been argued that artworks – particularly pictorial ones – can be the equivalent of ‘speech acts’ – that is, they can be used to do things, such as protest or endorse something. Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which depicts the Luftwaffe air raid that destroyed the town in the Spanish Civil War, has been described as a desolate ‘protest-painting’ and a ‘powerful antiwar statement’. Such actions – protesting, stating – are things we normally do with words. When we speak, we don’t merely express meanings; our words also have what J L Austin in 1955 called ‘illocutionary force’. When an officer shouts to her troops: ‘Open fire!’, she’s ordering them to shoot. But for an utterance to have a particular force, it needs to satisfy certain conditions. To order her troops to fire, the officer must have authority, and she must use words her troops can understand.

While Austin was mainly concerned with linguistic speech acts, he noted how they can also be nonverbally performed: consider silent protests or greeting another person by smiling. Such gestures must still be understood and recognised – what Austin called ‘conventional’. There are conventional gestures within artmaking and curatorial display, too. Recognisable methods of depiction with particular use of perspective and light, visual metaphors, iconographic symbols and curatorial conventions governing display will facilitate a work’s performance of speech acts.

Public memorials don’t just represent a particular person – they literally put them on a pedestal

If artworks can be speech acts or, at least, can express meanings with certain forces such as assertion and protest (a claim that requires further defence than I can give here), then presumably they can be harmful acts too, such as in straightforward hate speech – in racist, misogynistic or homophobic language. Hate speech constitutes and sometimes incites violence towards its target group. The utterance of ‘Blacks are not permitted to vote’ by a legislator during apartheid subordinates Black people; it ranks them as inferior, legitimates discrimination, and deprives them of important powers.

In parallel to this are the statues of slave traders and white supremacists. These public memorials don’t just represent a particular person – they literally put them on a pedestal. Through various aesthetic conventions, statues commemorate and glamorise the person and their actions and, in doing this, they rank people of colour as inferior, legitimising racial hatred. As the mayor of London Sadiq Khan said after a monument to the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston was torn down in Bristol in June 2020: ‘Imagine what it’s like as a Black person to walk past a statue of somebody who enslaved your ancestors. And we are commemorating them – celebrating them – as icons…’ And look again at Jones’s sculptures. The male artist depicted women as furniture within a society where women are still treated as secondary citizens. Regardless of the artist’s intentions, it’s thus plausible to interpret the work as amounting to a kind of sexist speech: it subordinates women by depicting us as household objects, ranking us as inferior and legitimising misogynistic attitudes.

Artworks speak, act and have concrete consequences for people’s lives. Recognising artistic speech or expression reveals a distinctive potential harm towards marginalised groups. So how should we manage it?

It’s our right to express views in public without fear of being silenced or punished, a right preserved (though not always upheld) under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This includes not just ordinary speaking but other forms of expression such as works of art. But as John Stuart Mill argued in On Liberty (1859), this freedom isn’t absolute – most philosophers and lawmakers believe that there must be some limits. Yet some legal restrictions are less stringent than others: the US First Amendment affords protection to some racist hate speech, for example – far more than the laws of the UK, Australia and Canada do.

Some have argued for stricter regulation of hate speech because of the nature of its harm. As well as having pernicious consequences, such as breaking the social peace and causing grave offence with psychological damage to target groups, such speech might also constitute harm in itself, by amounting to actions such as subordination – sustaining hierarchy and legitimising oppression. The legal scholar Jeremy Waldron, for example, sees the harm in hate speech as both causal and constitutive. He treats hate speech as a kind of group libel, which assaults the dignity of its target groups, thereby undermining their free speech.

Some theorists, Waldron included, think that such speech should therefore be banned in the quest for a just society, which publicly upholds the dignity of all persons. Such a call for tougher speech legislation could mean banning any works of art that, via their hateful messages and acts, cause similarly damaging social consequences or enact harms such as subordination. So, should we forever hide away Gauguin’s paintings? Quietly remove all Confederate and slave trader monuments?

It’s commonly assumed that artworks are special and should be almost immune to censorship; silencing artists is often considered deplorable. One familiar objection, expressed by museum professionals such as Vicente Todolí, former director of Tate Modern in London, is that censorship would mean losing great art. Indeed, several people present at the National Gallery debate in London said that taking down Gauguin’s works would mean losing ‘genius’ and ‘beauty’. Given that aesthetic experiences are considered valuable, this loss would apparently be regrettable.

Moreover, under the First Amendment, for example, many artworks that express hateful messages would be protected as legal expression because it’s hard to show that they incite violence. Indeed, it’s notoriously difficult to prove that particular artworks directly cause criminal behaviour. Meaning in art is more complex than ordinary speech, and the artist could deny having certain communicative intentions for their artwork, and so be let off the hook.

We can challenge, refute or even undo the harms of hate speech with more speech

A different kind of concern about censoring harmful art is that doing so might sweep under the carpet problematic canons and past atrocities. Such erasure could even result in a widespread amnesia (at least within dominant groups), where many won’t adequately confront our true history. Removing statues and paintings without anyone noticing might not properly engage with the problem in the first place; it could even be tantamount to dismissing the magnitude of the atrocities honoured by the monuments, or the immoral messages expressed by the paintings.

Instead of censorship, some have opted for an alternative response to hate speech. We can challenge, refute or even undo the harms of hate speech with more speech. Speaking back presents counternarratives and counterevidence to the falsehoods expressed. This might involve publicly denouncing instances of hate speech and affirming the dignity of the groups targeted, or refuting transphobic speech in social media forums, or challenging racist speech on public transport or at home.

As the philosopher Rae Langton argues, we can also ‘undo’ hateful speech from the inside, by dismantling the conditions needed for the speech act to have its force in the first place. As we saw, some speech acts require the speaker to have authority. And some presuppose content that gets smuggled into the ‘conversational score’. For instance, saying: ‘Even George could win’ presupposes that George is not a promising candidate, signalled by the ‘even’. According to Langton, this serves as a ‘back-door’ speech act that, if left unchallenged, gets accommodated and added to the ‘common ground’, changing what’s permissible to think and infer about the discussed subject. It becomes accepted that George is ranked as inferior.

We undo such speech by being active hearers. Langton observes how we can ‘block’ presuppositions and their back-door speech acts: ‘Whaddya mean – even George could win?’ Calling out presuppositions spotlights the content that might otherwise have gone under the radar. Once exposed, this content can then be challenged or rejected, preventing it from entering the common ground.

The harm of much hate speech is implicit. Degrading representations of target groups are sometimes presupposed rather than explicitly stated; the political theorist Maxime Lepoutre writes: ‘Instead of saying “Blacks are lazy”, someone might say “Even Blacks would do that job,” thereby implying that Blacks are lazy.’ As hearers, we can reject what’s presupposed, we can say: ‘What do you mean, even Blacks?! We don’t condone those views around here!’

Moreover, much hate speech subordinates because it’s expressed with authority, enabling the speech to rank a group as inferior. A white man racially abusing an Arab woman on the subway will gain authority when passengers don’t object. But if a bystander were to respond to the speaker with ‘Who do you think you are!?’, the presupposition of authority is rejected, and the speech loses its subordinative force.

Counterspeech, in particular this ‘blocking’, can illuminate parallel artistic and curatorial strategies to counter hate speech such as sexist paintings or racist monuments. The idea is that we should fight visual hate speech with artistic interventions and better curation; a kind of ‘curatorial activism’, as the feminist curator Maura Reilly put it in 2018. This approach has the distinct advantage of avoiding the issues with banning problematic art. I shall introduce just a few such strategies, although this is by no means an exhaustive list.

First, manipulation of an artwork and its curated space. Consider the Duke of Wellington monument in Glasgow, commemorating the military leader who led British armies to extend the East India Company’s control. The friezes around the statue depict the duke sacking Indian cities and slaughtering South Asians. For many years now, the statue has had a traffic cone on its head. Thought to have originated as a drunken joke, this action has taken on new significance. Amid protests after the murder of George Floyd, the cone was replaced with a Black Lives Matter (BLM) substitute. Consider also political vandalism and the addition of new artworks. The Robert E Lee Confederate monument in Virginia was spraypainted with ‘Blood On Your Hands’ and ‘Stop White Supremacy’ by BLM protestors, and was targeted with projections of Floyd’s face, bearing the words ‘No Justice, No Peace’. The defaced monument is now deemed one of the most influential American protest artworks since the Second World War. And on antislavery day in 2018, the art installation Here and Now appeared beneath the Colston statue in Bristol. The work took the shape of a slave-ship hull, with concrete figurines as cargo.

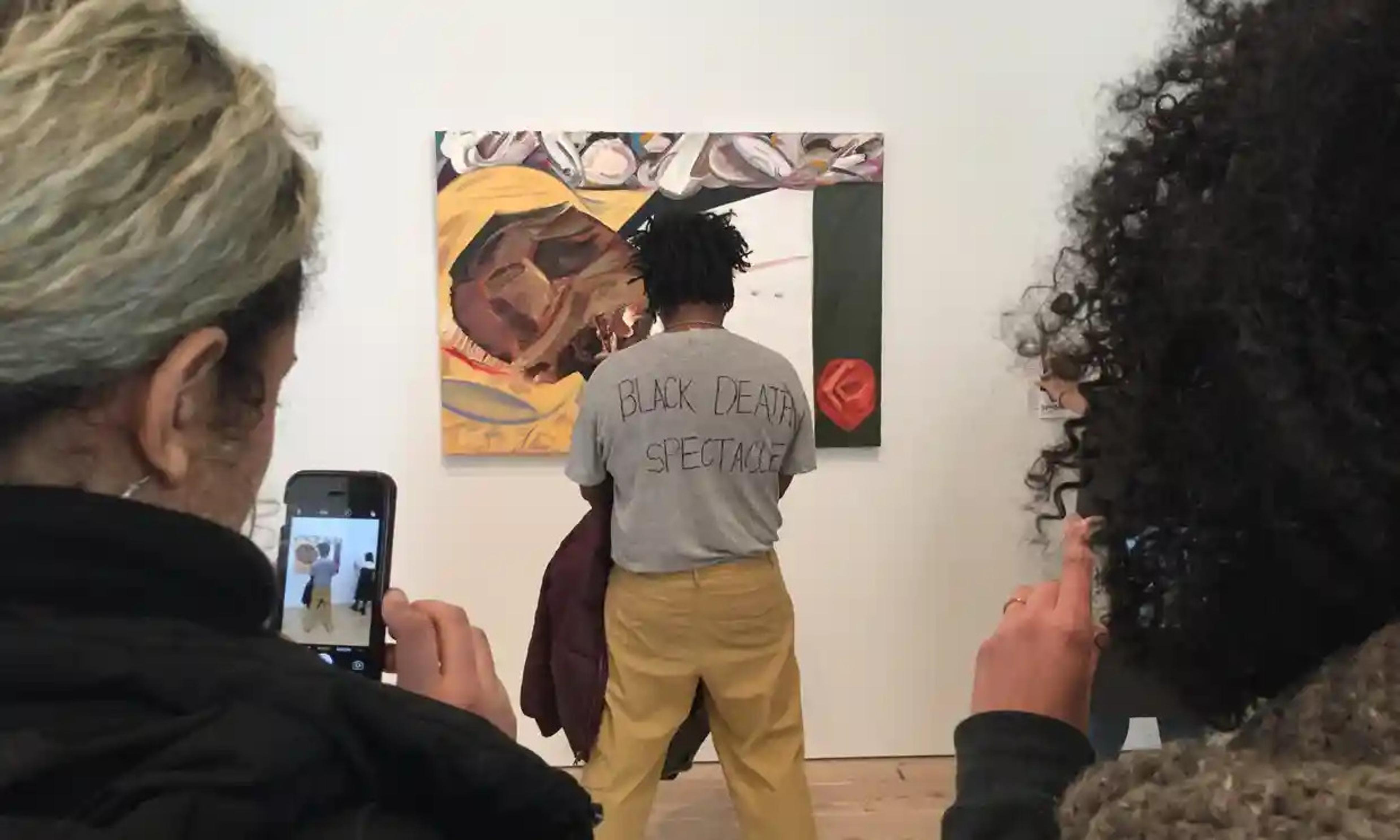

The artist Parker Bright protests Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket. Photo courtesy Twitter/anonymous

There are also interactions with pieces in galleries. In her painting Open Casket (2016), based on the mutilated face of the teenager Emmett Till who was lynched in 1955, Dana Schutz was accused of cultural appropriation in using Black pain as ‘raw material’. In response, the artist Parker Bright stood in front of the painting wearing a T-shirt reading ‘BLACK DEATH SPECTACLE’ and spoke about the work’s harms: ‘no one should be making money off a Black dead body’.

Artistic curation can recontextualise pieces, prompting the viewer to look again

Second, transparent curation. A few days before a Gauguin exhibition opened at the National Gallery of Canada in 2019, the curators edited some of the wall texts to avoid culturally insensitive language. Gauguin’s ‘relationship with a young Tahitian woman’ was changed to ‘his relationship with a 13- or 14-year-old Tahitian girl’. And consider Michelle Hartney’s Performance/Call to Action (2018), in which the artist placed #MeToo-inspired wall labels next to paintings by Picasso and Gauguin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to underscore their transgressions. For example, next to Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women (1899), Hartney quoted an essay by Roxane Gay: ‘[I]t’s time to say that there is no artistic work, no legacy so great that we choose to look the other way.’

Curation tells stories about the work on display, and curators have a responsibility to give accurate and true narratives surrounding the art. Facts shouldn’t be suppressed to furnish more convenient narratives obscuring truth. Artistic curation such as Hartney’s recontextualises these pieces, exposing the violent reality behind them, prompting the viewer to look again and reconsider their sometimes-dismissive attitude to artmaking contexts.

Such recontextualisation can also be done with museum pieces. Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992) rearranged the existing objects of the Maryland Historical Society to highlight the African American and Native American history behind these pieces, for example by placing slave shackles next to silverware in a cabinet. Curatorial strategies can also prompt debate about art censorship and interpretation itself. In 2018, in response to the #MeToo movement, Manchester Art Gallery temporarily removed John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) – which depicts naked young nymphs seducing a man – to question the presentation and narrative of the female form in the gallery. Visitors then recorded their thoughts on Post-it notes placed over the empty space.

Memorials of historic figures use a familiar aesthetic: they’re normally raised high on plinths, echoing an artistic convention where figures with the most power are depicted as larger. Literally raising high a person responsible for racist and colonist violence celebrates their actions and treats them as admirable. This smuggles in content: that slavery is permissible, which thereby ranks Black people as inferior, and so on.

But visual equivalents of ‘blocking’ are apparent in the above counterspeech examples, where the subordinating force of a piece’s speech act is disabled. Placing traffic cones on formidable and imposing monuments (see also the American Civil War statue in Colorado) undermines and dismisses the authority of the commemorated person and what they stand for – a visual ‘Who do you think you are!?’ It acts as visual bathos: reducing the figure’s presence with a banal object. After the Colston statue came crashing down, it was rolled through the streets of Bristol and pushed into the canal water, in what could be seen as dramatic ‘re-curation’ of the piece. This had the visual and sonic effects of humiliation; a rejection of the honour previously surrounding the slave trader. Such artistic manipulation can call out a work’s harmful content to stop it being accommodated, thereby undoing its subordinating force. By disrupting the gallery space, Bright physically blocked the back-door speech acts made by Schutz’s painting: that it was permissible for a white artist to aestheticise a brutal racist killing.

Similarly, transparent and honest curation highlights the content of the art on display. The fact that the Titian painting is beautiful doesn’t excuse or permit sexual violence to be romanticised. If curatorial information ‘spotlights’ that a work is eroticising sexual violence, then it prevents accommodation of the claim that eroticising such violence is permissible. Equally, proper contextualisation of museum pieces stolen amid imperial violence is a step in the right direction, albeit falling short of rightful repatriation.

Protest art gives marginalised groups positions of power from which to shout back

How effective is artistic counterspeech? Philosophers have noted the limitations of counterspeech more generally if speech doesn’t happen on an equal playing field. Normally, those targeted by hate speech hold less power, making speaking back difficult (for example, women’s testimony has historically been taken less seriously). There are also epistemic difficulties: the harm in much of hate speech isn’t explicitly stated and can be hard to unpack.

Artistic and curatorial strategies might to some extent sidestep these issues. Placing a cone on a statue’s head doesn’t require much cognitive labour in unpacking what the statue is saying and presupposing: the action itself swiftly opens up discussion, which then exposes the harm of the monument. Moreover, protest art can offer collaborative activities with graffiti, dramatic curation or performance, which give marginalised groups better positions of power from which to shout back.

However, there are still limits to such counterspeech. The Colston statue in Bristol was soon replaced by a figure of a BLM protestor: a Black woman named Jen Reid. This sculpture by the established, white male artist Marc Quinn caused a backlash: some argued that he was hijacking experiences of Black pain to further his career, and that it would have been more appropriate for a Black artist to produce an alternative statue. This suggests that sometimes creative responses should be reserved for the target group alone. Moreover, some responses still carry a social risk: the ‘Colston Four’ charged with criminal damage will go on trial this December for ‘drowning’ the statue.

Some responses to harmful art will inevitably be redescribed as vandalism, thus causing legal issues. But not reacting to such works can carry even greater risks to society due to the implied collusion or indifference to the issues such works raise. I’ve mentioned just a few activist strategies to manage dangerous art; there are also methods that highlight marginalised artists, such as new retrospective exhibitions, as well as decolonising and democratising art education through platforms such as the Black Blossoms School of Art and Culture in the UK.

Outright censorship is rife with problems generally, let alone art censorship, which is far more complex than straightforward speech. So we need to find new ways of signalling our disquiet, disgust and outrage at art that perpetuates social injustice. As the Bristol poet Vanessa Kisuule puts it: ‘I’m not necessarily for getting rid of statues… I want people to scribble on them, to make counteractive art about them.’ Curatorial and artistic responses are the way forward here; complacency certainly isn’t.