Four different writing systems have been used in Algeria. Three are well known – Phoenician, Latin and Arabic – while one is both indigenous to Africa and survives only as a writing system. The language it represents is called Old Libyan or Numidian, simply because it was spoken in Numidia and Libya. Since it’s possible that it’s an ancestor of modern Berber languages – although even that’s not clear – the script is usually called Libyco-Berber. Found throughout North Africa, and as far west as the Canary Islands, the script might have been used for at least as long as 1,000 years. Yet only short passages of it survive, all of them painted or engraved on rock. Everything else written in Libyco-Berber has disappeared.

Libyco-Berber has been recognised as an African script since the 17th century. But even after 400 years, it hasn’t been fully deciphered. There are no long texts surviving that would help, and the legacy of the written language has been one of acts of destruction, both massive and petty. That fate, of course, is not unique. It’s something that’s characteristic of modern European civilisation: it both destroys and treasures what it encounters in the rest of the world. Like Scipio Africanus weeping while he gazed at the Carthage he’d just obliterated, the destruction of the other is turned into life lessons for the destroyer, or artefacts in colonial cabinets of curiosities. The most important piece of Libyco-Berber writing was pillaged and sold to the British Museum for five pounds. It’s not currently on display.

But Libyco-Berber also reveals a more insidious kind of destruction, an epistemological violence inflicted by even the best-intentioned Europeans. There are numerous stories of badly educated, arrogant Europeans insisting that Africans not only never did, but never could, write books. Even as sensitive a philosopher as the French sociologist and theorist Pierre Bourdieu, who had deep personal ties to Algeria, and who supported the Berber/Amazigh cultural movement, could essentially make the same assumption. He insisted that the Kabyle people, whom he lived among and studied for years, were pre-literate, although they used (and still do) the characters of Libyco-Berber. Bourdieu’s is a cautionary tale for intellectuals who are committed to social activism. The passion – the need – to do what’s right is all too often steered by the conviction that, precisely because we’re intellectuals, we know what’s right. For Bourdieu, for example, the very ability to think, to reflect about what’s right, is tied to literacy.

But Bourdieu’s observational mistake – the idea that the Kabyle weren’t literate – is actually not his most consequential misapprehension. That would be the idea that literacy is a supreme cognitive and cultural achievement. It’s one of the means by which universities shore up the value of their intellectual work – they police grammar, philology, literacy – in short, they define and champion rigour and ‘standards’. For those of us brought up within that system – even brought up, as I was, in a former colony (Kenya) – those standards might appear to be value-neutral. But they’re value-neutral only because they annihilate even the possibility of other values, of other modes of thinking or being. When Bourdieu went from the elite École Normale Supérieure to a Kabyle settlement, he saw, ultimately, the absence of what made the university, and his own mind, what it was. That supposed absence is the product of intellectual arrogance, yes, but it’s also part of a European cultural heritage.

There’s a depressing familiarity to the assumption made by Europeans that Africa is a site of lack. But that supposed lack is something that Europe has counted on since the destruction of Carthage. Indeed, the destruction of that ancient city by lake Tunis could lay claim to being the very lack at the centre of European intellectual culture. But that’s another story. At one point, Carthage was poised to become the greatest empire on Earth. It failed only because the great Carthaginian general Hannibal didn’t destroy Rome itself when he invaded Italy. If Hannibal had succeeded, Punic rather than Latin might have been the language of European intellectuals until the post-Enlightenment. Bourdieu’s own language might not have been a ‘Romance’ language at all, and his most famous term, ‘habitus’, might have been a Punic word. But then his whole project wouldn’t have assumed Africa to be a place deficient of literacy. Bourdieu might have been studying pre-literate Romans instead – or never have had the chance, as a member of a pre-literate group in the remote mountains of southern France.

When the Romans destroyed Carthage in 146 BCE, its libraries of Punic literature were either burned or dispersed among nearby Numidian leaders. A few of these were later translated into Latin, although none of them have survived, and there are only allusions to what might have been in them. The only exception is a treatise on farming by a Carthaginian writer named Mago, which was translated into Latin and widely quoted. But Mago’s treatise itself hasn’t come down to us. As a spoken language, Punic survived for several hundred years. Augustine, growing up in what’s now Algeria, was certainly acquainted with it, and referred to it later in life as ‘our’ language, the language of we ‘Africans’. He even defended it against some snob in the city of Madauros, where he’d attended grammar school: ‘Many words of wisdom have been committed to memory in Punic books,’ he said, ‘as is disclosed by very learned men.’

Punic also survived in numerous inscriptions in stone throughout North Africa and the Mediterranean, as far east as the Anatolian plateau in Turkey. Most of these inscriptions are on funerary stelae, stone slabs that marked graves. They tend to name the deceased person (and sometimes his or her ancestry) and include a short prayer or dedication to a god. They might sometimes imply that a child sacrifice has been made to the god of Carthage, Baal Hammon, or to the city’s goddess, Tanit. (There’s still debate about whether Carthaginians really practised child sacrifice; explicit accounts are written by outsiders and, because no other texts survive, the only Punic accounts are the brief and enigmatic references on these stelae.) A second, and much smaller, kind of Punic inscription are temple tariffs, which list what portions of animal sacrifices belong to the priests. Because Punic is a Semitic language, it didn’t take very long for surviving inscriptions to be translated. Somewhere around 10,000 Punic inscriptions have been discovered so far and more are turning up, especially on seals and coins from archaeological digs. These appear frequently on the commercial and grey markets. As I write this, there is a Carthaginian coin for sale on eBay – for under $200 – with a single Punic letter on it.

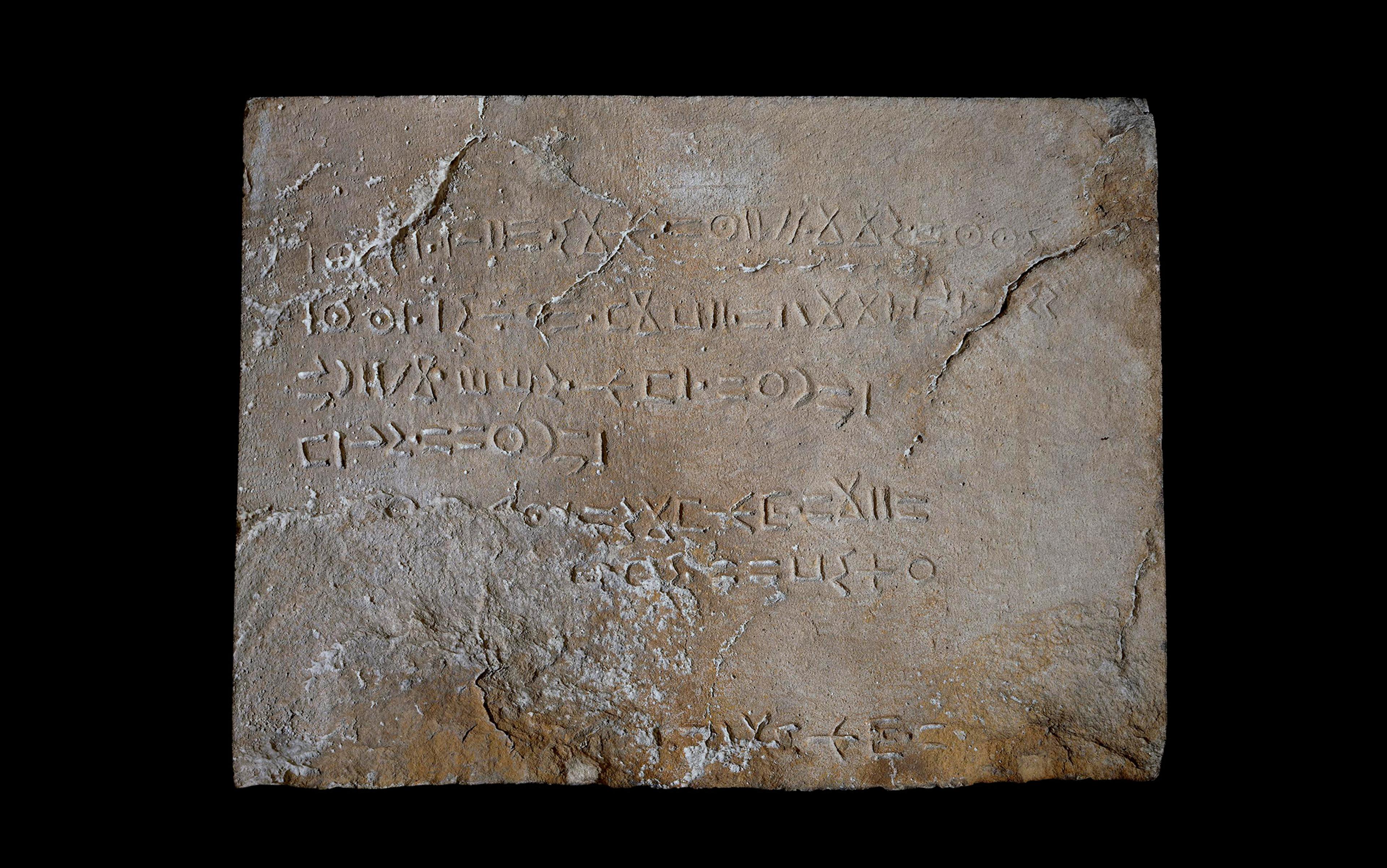

Limestone votive stela (c2nd century BCE) displaying 4 lines of neo-Punic inscription. In addition, a symbol of the goddess Tanit is flanked by caducei while above them are astral symbols. Courtesy the British Museum

From these meagre remnants the language was reconstructed, although the surviving texts don’t really amount to a ‘literature’ as such. In fact, the Classics scholar Denis Feeney has argued that the destruction of Carthage goaded the Romans into thinking of their language in exceptional terms, as a language that was, after the Punic Wars, the language of an empire. Rome needed texts that befitted the dignity of a world empire and so, by the time of Augustus, the great epic the Aeneid was written about the founding of Rome. Its first half is the story of how Aeneas left behind Carthage, whose queen, Dido, destroyed herself out of fury and grief. She embodies the trauma of a culture destroyed in a war that gave Rome supremacy over the Mediterranean.

As Augustine attests, Punic didn’t disappear suddenly in a violent conflagration. It disappeared gradually, in the kind of disdain and neglect for which Augustine called out his colleague. But even Augustine’s championing of Punic sounds defensive. He doesn’t talk about why he thinks it’s important, or even what kind of wisdom he finds in it. He has to appeal to unnamed scholars to back him up. Whatever wisdom was in them remains lost, and Augustine is probably the last writer with any knowledge of Punic to mention it as a spoken, living language. In the middle of the 6th century, the Greek historian Procopius refers somewhat vaguely to people near the Strait of Gibraltar still speaking ‘Phoenician’. After that, Punic passed almost entirely into silence.

‘Civilised’ traces of cultural practices across Africa were supposedly the remnants of ‘white’ refugees from Atlantis

The only fragment of Punic text that anyone could claim to understand for the 1,200 years after Procopius last mentions it appears in a play by the Roman satirist Plautus (from whose plays William Shakespeare borrowed heavily for his early comedies). In his Poenulus, the character Hanno is a Carthaginian who speaks 10 lines of Punic. Plautus translates it, and for more than a millennium that provided the only knowledge of what Punic might have been like. Plautus wrote only a phonetic equivalent of Hanno’s speech, so the Punic script itself remained undeciphered until the French scholar Jean-Jacques Barthélemy published an alphabet in 1758.

Punic is an ‘African’ language in the sense that it’s a dialect different from ‘Phoenician’, which was spoken and written throughout the Mediterranean in antiquity. What Roman Africans meant by ‘Africa’ isn’t always clear: sometimes they meant the tiny original foothold that Rome had, the province of Afer; sometimes they meant the territory not occupied by Numidia to the west, Egypt to the east and Nubia to the south; sometimes they meant the general sweep of what they knew of the continent as a whole.

For some, Punic might be a precariously ‘African’ language because Phoenician was dispersed well beyond Africa. That idea could be rooted in a deep assumption that civilisations in Africa are always to be regarded as originating elsewhere. When the Europeans came upon the magnificent medieval ruins of Great Zimbabwe in the 1870s, they had a great deal of difficulty in accepting that they could have been built by the ancestors of the Shona people who still lived there. They had so much difficulty, in fact, that they hypothesised – or even believed – that they had to have been built by a white – indeed Anglo-Saxon – race. Given that there’s absolutely no evidence that Anglo-Saxons ever inhabited sub-Saharan Africa until the 17th century, that posed a problem. It was a problem that was solved by arguing that the Phoenicians had colonised southern Africa centuries before. That was a solution only because the Phoenicians were regarded, for the purposes of this theory, as white.

The late-19th-century English writer Rider Haggard suggested in a series of historical fantasies about Great Zimbabwe that these Phoenicians were actually Carthaginians – but Carthaginians who were emphatically not ‘African’, not in the sense that they were of the same race as the ancestors of the Shona. The absurdity of this chain of reasoning is demonstrated by the eminent anthropologist Leo Frobenius, who believed that the ‘civilised’ traces of cultural practices found across Africa were the remnants of refugees from Atlantis, who were effectively ‘white’, and who also founded Carthage. For Frobenius, it was axiomatic that any kind of long-term cultural continuity could come only from ‘without’, as he termed it: ‘seed indigenous to the soil’ will be ‘forgotten’. Long-term traces of culture, for Frobenius, could have come only from outside Black Africa.

Libyco-Berber makes it very difficult to insist that no writing in Africa could have been indigenous. There are two theories about the age of old Lybic script. If it’s derived from Punic, then it couldn’t be older than the 10th century BCE, when Phoenicians arrived in North Africa. If Lybic script developed from pictographs, then it could be much older. Pictographs still on rock faces in the High Atlas mountains of Morocco could be older than 1,000 BCE, although it might be impossible to establish exactly how old they are. As with the question of whether Punic can be considered an African language, the relation between pictographs and Libyco-Berber itself is riddled with assumptions about the general conditions of literacy and forms of representation in North Africa across the centuries.

The newest inscriptions date from the 4th and 5th centuries CE, but the great 14th-century Arabic sociologist and historian Ibn Khaldun might have been describing a Lybic inscription that, he reported, included the name Suleiman. If he was right, that inscription suggests that the Lybic script was used after the arrival of Islam in Morocco in 680 CE, and possibly during Ibn Khaldun’s lifetime. Another possibility is that it never really did die out. One of the newer inscriptions was found in the tomb of a woman known as Tin Hinan, buried in the 4th century. Today she’s regarded by the Tuareg in the Hoggar Mountains of Algeria as their ancestral matriarch. Writing of Libyco-Berber in her book So Vast the Prison (1995), Assia Djebar says: ‘Our most secret writing, as ancient as Etruscan or the writing of the runes, but unlike these a writing still noisy with the sounds and breath of today, is indeed the legacy of a woman in the deepest desert.’

The Hoggar Mountains in Algeria. Photo by DeAgostini/Getty

The name ‘Libyco-Berber’ is really just the name of the supposition that modern Tamazight (Berber) languages descend from it. Two other names, Numidian and Old Libyan, are used less frequently, but they don’t smuggle in the assumption that we know much about the language itself because of the continuity of the script. The script it was written in, however, has been taken up recently as the official script of the Amazigh movement in the Maghreb, which is fighting for greater recognition of the Tamazight-speaking peoples. They call the script tifinagh, a word that’s often taken to mean ‘Punic letters’; -finagh is derived, perhaps, from Latin punicus. Another etymology argues that it’s the plural form of afnegh in Tamazight that means letter/character/sign; the verb ‘to write’ is efnegh. The first derivation frontloads the supposition that the script is derived from Punic writing; and, to separate both its form and its origin from Carthage, scholars tend to use the terms Libyc or Lybico-Berber to describe the ancient script.

Europeans have long found it difficult to believe that tifinagh is actually a script at all. A number of scholars who study the tifinagh-like designs that both Amazigh and Tuareg women use deny that these designs should properly be called ‘writing’ because they never have been. Berber dialects, as Susan Searight asserted in her 1984 book on Moroccan tattooing, ‘are not written down, and in fact never do seem to have been.’ Some anthropologists conceded that the designs that Amazigh women use might be related to the ancient script, but that it was no longer really writing. They were just ‘part of the repertoire of the designs relating to Berber art used in pottery decorations and tattoos’, as Yasmina Djekrif argued in 2007. In 1968, Victor Englebert called the chin tattoos of Berber women the ‘Remnants of a lost script … the last symbols of a tongue still spoken by the hill tribes but no longer written.’ These designs remain, for some contemporary scholarship, precisely art – that is, form that doesn’t directly mean something. It is, in other words, just art.

Writing, it was long believed, was something that Africans simply couldn’t do

The history of modern European encounters with the Lybic script is a history of neglect, false assumptions and outright destruction. Evidence was overlooked, lost or obliterated. A Numidian prince named Atban was buried in a magnificent tomb around the time of Carthage’s destruction. A plaque in the tomb, written in both Punic and Lybic, was discovered in 1631 by Thomas d’Arcos, who sent a transcription of it to a friend in France, where it lay neglected for a couple of centuries. The inscription’s next fateful encounter occurred in 1842, when Thomas Reade, Napoleon’s former jailer on St Helena, noticed it while he was the British consul in Tunis. Reade, whom a British officer once called aptly a ‘Nincumpoop’, tore the tomb down to get at the plaque and sold it to the British Museum for five pounds. He destroyed another plaque in doing so, but this surviving plaque, having been written in both Lybic and Punic, ultimately proved to be the key to deciphering Lybic.

Reade’s ‘Nincumpoop’ respect for what even he thought was ‘old African’ writing is an egregious example of the violence with which Europeans frame the potential of African premodern writing. Sometimes the violence is more symbolic, as was the case with Bourdieu. His extensive fieldwork among the Kabyle group of the Amazigh – an ethnically Berber people who live in Kabylia, in the Tell Atlas mountains – formed the basis for theories that would help shape contemporary thought: the habitus, the field of practice, symbolic capital, symbolic violence. Bourdieu was an ardent supporter of the Algerians in their war for independence, and he later assisted with the burgeoning movement of Amazigh identity and self-determination – which included the revival and widespread adoption of tifinagh.

So it’s especially surprising that Bourdieu referred to the Kabyle as a ‘society without writing’. For one thing, the Kabyle had had a written body of customary law for at least 130 years. French archives contain letters from Kabyle leaders and French colonial officers from the 1840s, from the Kabyles hired to record decisions made by and in the Bureaux Arabes, and a few poems written in Kabyle Berber. In a later work explicitly concerned with education – La reproduction (1970) – Bourdieu almost completely ignores Algeria, except to mention that Koranic schools beat their students, and to cite himself in a note on the social capital that a primary or secondary school diploma in Algeria gave graduands. There’s a substantial archive of poems, stories and texts on religion, grammar and medicine dating from the 17th century from the Anti-Atlas region of Morocco. And, of course, there’s the persistent presence of tifinagh and its ancestral memory of Lybic script.

Why would a thinker as sympathetic to the Kabyle as Bourdieu neglect so much evidence that, if they were, in fact, illiterate – and they were not – one could more accurately describe them as post-literate? Literacy, for Bourdieu, is no neutral or inert feature of culture. It’s ultimately the way that people come to a full consciousness of themselves, the way in which they can develop fully formed symbolic cultures. If you hear a hint of Hegelian teleology behind this, you’re probably right. You’re also right if you associate the undeveloped literacy of the Kabyle with Hegel’s own declaration that the peoples of Africa couldn’t fully enter into history.

Writing, it was long believed, was something that Africans simply couldn’t do. No one stated this more emphatically and confidently than the British explorer Hugh Clapperton, who in 1826 told Alaafin Majotu, king of the Yoruba Oyo empire, that he was ‘not like a black man, who has no book to write’. That declaration is so oblivious and arrogant that it doesn’t need a label on its case in the museum of colonial racisms. But other cases do. What I’m writing here is, in fact, just such a label on the Bourdieu display. In making the Kabyle a kind of historical artefact, a society from the past, Bourdieu just repeats, in another form, the Hegelian lie that Africans don’t have history.

Bourdieu missed, accidentally or not, a lot of evidence of literacy that would have complicated his theoretical work. But it would perhaps have been no more than an inconvenience. After all, proverbial sayings probably contained knowledge old enough to have been unaffected by the arrival of literacy along with colonialism. Proverbs exist because writing didn’t. Bourdieu’s overlooking the many forms of writing that could be found in modern Kabylia is not just nitpicking, an anecdote about how one of the greats fudged his work. Bourdieu’s blindness to African writing is bound up with ideas about history as progress, ideas that are strangely discordant with Bourdieu’s own opposition to colonial domination in Algeria. The denial of a writing that had existed for several thousand years is part of a systematic and philosophical embrace of a European historical vision: of history as the movement from the primitive and childlike other to a mature and modern self – which is found only in Europe.

In one extraordinary passage, Bourdieu uses the metaphor of child development to discuss the supposed awakening that literacy brings:

the shift from a mode of conserving the tradition based solely on oral discourse to a mode of accumulation based on writing, and, beyond this, the whole process of rationalisation that is made possible by (inter alia) objectification in writing, are accompanied by a far-reaching transformation of the whole relationship to the body, or more precisely of the use made of the body in the production and reproduction of cultural artefacts. This is particularly clear in the case of music, where the process of rationalisation as described by Weber has as its corollary a ‘disincarnation’ of musical production or reproduction (which generally are not distinct), a ‘disengagement’ of the body which most ancient musical systems use as a complete instrument.

Even if Bourdieu hadn’t invoked the German sociologist Max Weber, the underlying assumptions of Marxist historiography – that history is a dialectical elaboration, a development – are clear. Storytelling is replaced by something like capitalism, the ‘mode of accumulation’ and the ‘production and reproduction’ that writing allow. But Bourdieu does mention Weber, and in doing so implies that what’s being developed is more than just economic institutions: it’s the ‘process of rationalisation’. Weber means by this something like the overwhelming array of bureaucratic and technological mediations that seem inescapable in European and American modernity, if not almost everywhere in the world. But Bourdieu’s use of the term here also implicates a corollary assumption about the Kabyle: that they lack this ‘rationalisation’, even that they lack the faculty of fully ‘developed’ reason itself. Bourdieu is of course not overtly, or even consciously, endorsing crude historical schematisations of cultural development, but those schematisations are the consequence of thinking about writing without asking about its history. Merely to ask ‘When does writing begin?’ or ‘How does knowing how to write change things?’ is to require some kind of narrative of fulfilment or completion.

Bourdieu’s discussion of writing here doesn’t concern how writing is taught. But his discussion, pressured by the underlying logic that sees pre-literacy as a kind of ‘potentiality’, turns to a discussion of scenes of pedagogy. To explain how a society possesses knowledge without ‘rising to the level of discourse’ or even, more scandalously, rising to ‘consciousness’ itself, Bourdieu turns to the education of children. He doesn’t treat them as an example, strictly speaking, but as an explanation of the mechanisms by which an entire people could function without having access to ‘discourse’ or ‘consciousness’: children mimic actions, or learn ‘gnomic poems, songs, or riddles’ that embody a ‘small number of principles’. The seductive sheen of Bourdieu’s prose tends to distract one from the surprisingly crude colonialist tropes about Africans in this single passage: they lack the capacity for reason, they lack complex institutions, they prefer storytelling to technology, their base of knowledge is meagre, they’re natural mimics, they live much more fully in the body than in the mind.

Even when one tries to stand outside the policing of literacy, one cannot

Among other things, this story is a rebuke to scholarship. It tends to find what reproduces itself, what confirms its already underlying suspicions. It tends to re-sacralise itself, that is, to keep alive the medieval distinction between the holy orders and the laity. It was the difference between theology and practical belief, and it’s perpetuated by the idea, which goes back to the temples of Thoth in Egypt, that only a priestly class can truly read, that writing is best kept within a sacred precinct.

Even intellectual enquiry motivated by – or at least committed to – revolutionary principles, like Bourdieu’s certainly was, goes in search of knowledge that was there all along. It finds what has always marked the gap between sacred institutions and the laity: literacy. And literacy is imagined not just as the ability simply to read. It is hedged around with restrictions and rank: think about what it implies for Joe Biden to have called Barack Obama articulate, or what it means to worry about ending a sentence with a preposition. Even when one tries to stand outside the policing of literacy, one cannot. Every English professor in the anglophone world has had someone say to them that they’d better watch what they say: not because of its content, but only because of its form – because of what, finally, doesn’t really matter.

Djebar’s So Vast the Prison imagines the fate of Nubian writing outside of the search for ‘literacy’ by scholars who follow only the ‘traces left by clerks and notaries’. Their archive is impoverished not because it doesn’t contain much. It’s impoverished because there’s so much more that it could contain. For Djebar it includes, above all, an ancestral writing that lives in ‘the intractability and mobility of a people who, in a gesture of supreme elegance, let their women preserve the writing while their men wage war in the sun or dance before the fires at night.’

However, as the rest of Djebar’s book makes clear, this arrangement is anything but elegant. The dissymmetry of gender relations forces women out of the public spaces, cut off from the spectacular self-display of men at war and in the dance. It forces, and allows, a once-public language to become private, intimate and unknown to much of the population. For Djebar, this writing is also her own writing: ‘as I wrote,’ she says, ‘I recalled myself.’ French and Arabic, the ‘paternal’ languages in her book, are consequently the languages of forgetting, precisely because they’re the languages that insist on being seen and heard. The terrible irony, of course, is that Djebar can tell us, we non-tifinagh readers, only in French. We might have no choice but to use the language of the academy ourselves, but Djebar’s book shows us the necessity of humility, of listening for the silences where the language of the other might be. Her book – and the negative example of Bourdieu’s work – indicts those of us who wage scholarship as if it alone made a difference, whether by writing books to be read by specialists, or by thinking our radical pedagogy is the pinnacle of radicalism, or by saving the world one Facebook post at a time.

But we also need to look for wisdom where institutions train us not to expect it. The other seductive legacy of Bourdieu’s work is his theory that the old Marxist superstructure actually did matter a great deal – what Bourdieu called social capital was one of the propulsive forces of culture. In many ways, because of his audience – especially in the US, where French theorists tended to be read only by academics – Bourdieu’s work on social capital amounted to a theory of university power. That is, a theory that universities had power to change because they taught, and reproduced, knowledges that live more fully in the mind than in the body. They reproduce the kind of blindness that would make Bourdieu assume from the start that the Kabyle had never been literate.

Academic friends have expressed surprise when I tell them about spending time listening to local activists talk to, and about, the people who live around us in the decayed industrial city where I live. Their sentiment runs something along the lines of ‘I suppose activism can be local too.’ The trick for intellectuals is to imagine continually what’s actually obscured by what we read: the languages of people who don’t read Antonio Gramsci, or Paulo Freire, or Fred Moten. Darren Green, an extraordinary activist in Trenton, New Jersey, walks around 11 public housing projects every day, several of them more than once, to talk with, and listen to, the people who live in them. He likes to say that the elderly are like walking bookshelves. As the example of Bourdieu shows, even the most intellectually committed, even the smartest – perhaps especially the smartest – of us can all too easily overlook the script of those lives, the language that might remain hidden for too long.