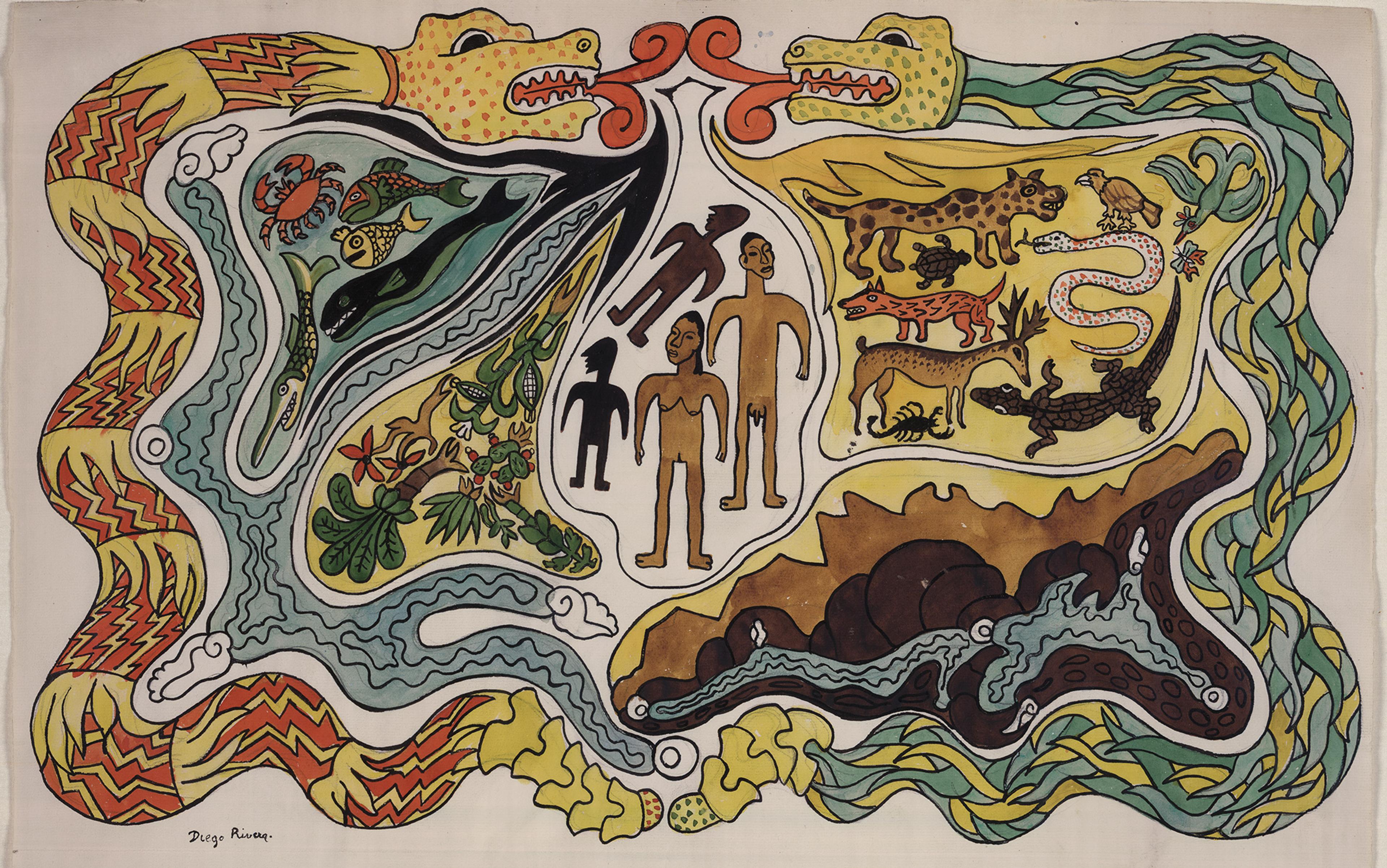

Animals are everywhere in the Popol Vuh. They leap and lick and crawl and bite and squawk and hoot and screech and howl. They are considered sacred, not as disembodied beings in some faraway place, but in their coexistence with humans, day by day in the forests. The Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent, with its gorgeous blue-green plumage, birthed the world from a vast and placid ocean. The Popol Vuh provides the narrative of this creation of humankind and the subsequent mythology, history and culture of the K’iche’ Mayan Indigenous people in central highland Guatemala.

Animal, human and godlike worlds form a flowing whole, communicating and shapeshifting, engaged in relations of love, friendship, rivalry, instinct. In the Popol Vuh, humans don’t domesticate or sentimentalise animals, but recognise their form of existence. They hunt them, send them on errands, take down their messages from gods, sacrifice them, play games with them. The animal was not a lower being, over whom, as the Europeans believed, God had granted man dominion. For the K’iche’ Mayans, animals were neighbours, alter egos and a form of communication with the gods.

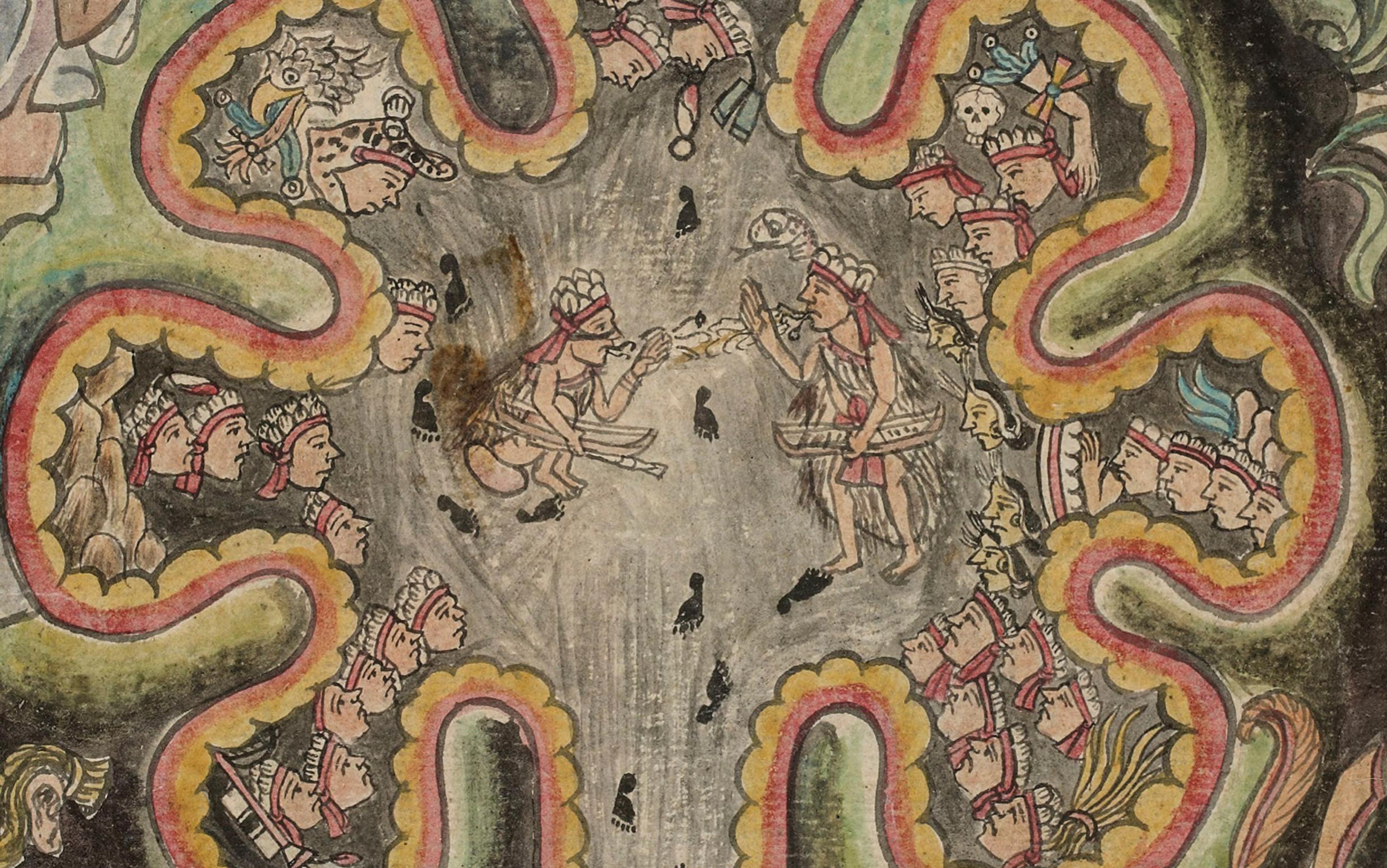

The first half of the Popol Vuh is circular and mythological, drawing from a mystical notion of time linked to the firmament. The second half is more historical and linear, chronicling events from the reigns of Mayan kings to the tragic arrival of the Spanish colonisers. Based on oral and performative traditions, the Popol Vuh as a whole displays a fascinating self-awareness about the changing relationship with gods and animals, in which new ideas of morality, sedentary existence, subservience to gods who offer temporary happinesses, such as food and women, and control over animals differ from the more fluid arrangements of times before, preceding and possibly auguring the Spanish conquest.

Originally written on bark or deer skin, the Popol Vuh was compiled by nobility in the town of Santa Cruz del Quiché around 1550, during the first years of colonialism. The work draws on lost narratives that stretch back to a more ancient, pre-Columbian past. Today, it is often still referred to as the Mayan Bible, even if putting an adjective before the religious book of another tradition doesn’t do justice to the way that the Popol Vuh’s ideas about selfhood and animality parallel at times, but frequently diverge from, those of the Catholic tradition.

In the first half of the Popol Vuh, animals are messengers for gods and men, able to communicate with both groups as well as each other. They are by turns vengeful and collaborative, working together to thwart plans (a concerted ganging-up) or push them along (a coordinated helping-out). Animals can be obliging beings; a horde of ants assists Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, twins and heroes of the Popol Vuh, to drive their enemies from the ravine to the road. The animals aren’t necessarily magical, so much as practical and wily. Black howler monkeys, jaguars, rattlesnakes, armadillos, bats, louses, toads, snakes, hawks, owls, wild boars, turtles, rabbits, doves, mosquitos, red and black ants, and other species – there are more than 30 – appear on the scene and often steal the show.

Imagine a line of ants sprints past, a flash of fur, a pair of shining eyes in the dark. A butterfly with a striking turquoise pattern flutters its wings. These are beautiful, ephemeral, needed. People, in the Popol Vuh, are created thanks to animals. Hunahpú and Xbalanqué are born because owls connived with their mother to trick the lords of Xibalba. Before that, gods attempt to create the very first people from mud, then from wood, but they fail. At last, mountain cats, coyotes, small parrots and crows bring the corn that the gods use to make maize dough, grinding it into drinks nutritious enough to build strength. In this culture, corn is at the base of everything.

Animals also perpetrate violence, amorally, frequently and – to modern human tastes – needlessly, just as a cat’s swatting about a mouse seems gratuitous. Humans sport with and bully nature and gods just as young boys do, taking a break from football and blowgun-shooting, not out of any particular malice, just because they’re on the same court at recess. Instead of a world with a mute god lording over well-behaved people, here are men and gods in a situation of fractured and antagonistic communication, with animals a constant presence in the middle, aware of what’s going on, taking part. Never just background, they are essential to its brimming, throbbing, pulsing world.

The Mayans accept the animistic and vital force of the animals that surround them

People venerate dogs but also kill them for sport, sometimes resurrecting them (without their being consulted). Monkey faces are laughed at and other creatures are killed, roasted, smeared in white chalk, offered as false gifts and subjected to physical deformities at the hands of humans and gods, often as origin stories for their current form – the rat’s tail burnt by fire to become hairless, the owl’s mouth cleft in two as punishment. Animals are easily placated by bones and food, killed and tricked, enlisted to aid in others’ projects. The heads of pumas or jaguars are employed for a ball game, fireflies are used to light cigars, and insects and owls are pushed into the harsh world, a postal service free of charge.

What can explain this passivity? Why should the animals work for anyone else? Why don’t they engage in a massive coordinated revolt? They’ve shown, after all, that they have the power to organise in groups. And they’re able to communicate across species. In Mayan thought, physical bodies are sometimes treated with nonchalance because it’s the spirit that survives, and bodily transience is taken as a part of life. So on earth and in Xibalba – the underworld or the place of death where the gods live, divided into six houses: Dark House, Rattling House, Jaguar House, Bat House, Razor House and Hot House – animals constantly meet their death.

Yet within the complex Mayan mythology, animals remain an indispensable and sacred part of the world, with elements of both the humans and the gods. The three groups are not clearly separated, and there is movement between physical bodies just as in systems of thought such as Hinduism, in which a soul assumes different physical forms. When the hero twins die in Xibalba, confronting the lords of death on the ball court, their ashes are thrown into a river and revive as hybrid people-fish. The Mayans accept the animistic and vital force of the animals that surround them, flowing through but not limited to a single physical body.

Over the course of the Popol Vuh, the human relationship to the animal changes, as humans themselves change. There is a great flood. From the first to the second part of the manuscript, humans are cut off from their relationship with nonhuman life, which includes animals, plants, the divine. The gods begin to feel threatened by the new humans, and take away some of their abilities:

Then the Heart of Heaven blew mist into their eyes, which clouded their sight as when a mirror is breathed upon. Their eyes were covered and they could see only what was close, only that was clear to them. In this way, the wisdom and all the knowledge of the four men, the origin and beginning, were destroyed.

Ignorant, humans no longer appreciate staying together; they divide. From a common origin, they split into different languages with different gods. They grow hungry. They eat bark and smell the ends of their walking sticks to fool their stomachs. They migrate. Some have fire, others don’t. It’s freezing; those without fire shiver. At last, thanks to incense offerings, the sun comes out, making not just humans but all animals happy; they must have been cold too. The puma and jaguar roar, the eagle and white vulture and other birds sing and stretch their wings. But now the sun is too harsh; it dries up everything and turns the most ferocious animals to stone.

The ‘new generations of men’ who survive begin worshipping the faraway and distant heavens. In the process, something odd happens. The humans gain souls, yet also become more ‘animal’, coordinated as groups but not questioning their condition. Thoughtlessly, they work on behalf of the tribe. At the same time, nonhuman animals recede from the panorama.

The new god-worshipping humans see animals as a rival to consume, or copy them to acquire their powers

No longer go-betweens, the animals in the second half of the Popol Vuh become something to copy, a power to channel. The new humans no longer work with them; now they want to be them. The insignia of royalty for the new human kings, as well as gods, is animal: puma and jaguar claws, heads and feet of deer, snail shells, and lots of feathers – from parrots, herons, red and blue macaws, raxons or cotingas, and quetzals. The kings take on the names of animals, and certain kings have the power of metamorphosing into other creatures. King Gucumatz, for instance, can turn into an eagle or jaguar, as well as clotted blood. The less lofty humans wear deer skins and eat whatever animals they can find.

The new god-worshipping humans see animals as a rival to consume, or copy them to acquire their powers. Now the sacrifices, both animal and human, begin in earnest. The gods chase human women, and ask for offerings. First, they take creatures of the woods and fields, female deer and birds. Then they want more. Priests pierce their own flesh with stingray spines to extract human blood, but the gods remain hungry. Balam-Quitzé, Balam-Acab, Mahucutah and Iqui-Balam, the first men of maize, start to abduct men, and kill entire tribes on behalf of sacrifice. Gods pretend to be coyotes, mountain cats, pumas and jaguars, making their noises to trick humans. Men fight back, making capes embroidered with the designs of animals. Much blood is spilt. The last pages of the Popol Vuh are a melancholy recitation of lineage, the names of kings and great houses.

This is when the Spanish arrive, to hang the kings and turn the buildings to ruins, homes for owls and wildcats. The Popol Vuh is the account compiled by anonymous K’iche’ authors a few decades later. Thus, we read:

Here we shall write. We shall begin to tell the ancient stories of the beginning, the origin of all that was done in the citadel of K’iche’ among the people of the K’iche’ nation. Here we shall gather the manifestation, the declaration, the account of the sowing and dawning by the Framer and the Shaper, She Who Has Borne Children and He Who Has Begotten Sons, as they are called; along with Hunahpu Possum and Hunahpu Coyote, Great White Peccary and Coati, Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent, Heart of Lake and Heart of Sea, Creator of the Green Earth and Creator of the Blue Sky, as they are called.

Mayans’ interest in their own past precedes the arrival of the Spanish colonialists, and the Popol Vuh comes at a moment of double crisis, as the arrival of the Spanish brings violence, destruction and cultural death. It is difficult to map these events on to a Roman calendar, given the Mayans’ own sophisticated cyclical calendars, astronomical systems, sacred almanacs, attempts to express history pictorially in hieroglyphical forms, and dream and visionary narratives, all of which use different forms of historical organisation than linear chronological time. Yet the Mayans’ own mythological narrative does chronicle a shift in the relationship with animals, the natural world and the gods. An open book, however, it leaves open the possibility that these events might herald a return or further transformation.

A century and a half after the Spanish invasion of Guatemala, in 1701, the Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez came across the K’iche’-Maya account in the town of Chichicastenango, where the manuscript had been moved. He started on his translation into Spanish as part of a project to evangelise natives – ‘contemplare et contemplata aliis tradere’ (study and pass on the fruits of your study) is the motto of the Dominican Order. Ximénez didn’t give the translation a title at first, just included it inside his big volume Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala. In the 19th century, the Austrian explorer Karl von Scherzer came upon the text and copied it out. The French writer Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg took a shortcut and simply stole the book from the library of the University of San Carlos in Guatemala, at a time when the country was in turmoil, and, as Bourbourg himself put it, manuscripts were ‘tossed on the floor in a dark, humid room’ and ‘anyone was free to pillage and plunder’. It was his translation that supplied the catchier title Popol Vuh. The stolen copy found its way, eventually, to Chicago’s Newberry Library. These multiple layers of translation and reception also form part of the Popol Vuh.

The Spanish empire and colonial project, closely identified with the Catholic Church, brought many acts of great destruction against Indigenous peoples. In Yucatán (also home to Maya peoples), the 16th-century Franciscan friar Diego de Landa gained the Indigenous peoples’ confidence before sending vast numbers of their books written in hieroglyphs to the bonfire.

Ximénez came to Mesoamerica a century and a half after Landa. He was a Dominican, and as such believed man possesses a God-given reason, linked to intellectual culture and soft methods of persuasion rather than physical violence. The Dominicans prized reason as given by God’s grace to be humans’ most important attribute, and the way to perfect nature, as the Dominican Saint Thomas Aquinas had philosophised. In Ximénez’s eyes, the priest’s task was to help draw out and encourage the use of reason in those with less of it. A studious man, he saw Indigenous peoples as less complete in reason than those of his Catholic tradition, but not as barbarians devoid of intelligence.

For the Mayans, ‘reason’ was never of paramount value. The body and the community were of greater importance

With these premises, Ximénez’s work to learn the K’iche’ language, translate the Popol Vuh and provide an interpretation rescued a Mayan sacred work from oblivion. Ximénez did believe the Indigenous should be converted as they were under the influence of the ‘father of lies’, Satan. But he took Mayan religion seriously enough to compare it in his prologue to European heresies by Arius, Luther, Calvin and Muhammed, formidable adversaries and fervently debated by Dominicans. Ximénez was willing to consider the reason of his opponents, rather than, as Landa had done, burn their books.

It is a glorious irony that Ximénez rescued a work that gives animals such agency, personality and strength at a time when ‘animal’ had become an expression of scorn and disrespect. Ximénez himself thus formed part of an 18th-century critique of European colonialism, a dissidence from within the Dominican order as it underwent internal crisis. The Dominican premise that all men have reason meant, in theory, that it was possible to peacefully evangelise by persuading the other to one’s side. Yet in the five centuries since the order’s founding, consciousness had grown that this technique required coercive methods to work in practice. Such violence was clear in both the Americas and the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions, with Tomás de Torquemada, the notorious inquisitor, being a Dominican.

Ximénez was not the only missionary sceptical of European imperialism and its methods. A number of Dominican friars, including Antonio de Montesinos, Pedro de Córdoba and Bartolomé de las Casas, offered accounts about how attempts to convert the natives involved violence. Although they weren’t openly militant like other orders, the Dominicans saw their calm appeals to ‘reason’ become involved in situations requiring the application of force.

Reason is always embodied, and what affects the body affects the mind. Physical conditions and environment influence thought, and sentiments and sensations can be as consequential as logical deductions. This is why, for the Mayans, ‘reason’ was never a category of paramount value. The physical body and the community were of greater importance, inseparable from any notion of the soul.

In the Popol Vuh, the human separation from the gods and the animal world thus marks a change that it would be fascinating to compare with the Catholic fall from grace. Mayan religion was concerned with the body – not just the human body, but the bodies of animals and gods. The fluid Mayan reality between divine, animal and human bodies, and the lament over their separation, was a lament over the loss of this physical freedom.

Ximénez either worked from a text given to him by an anonymous Indigenous person, a transcription – never found – of oral K’iche’ language into characters, or else directly transcribed an oral recitation. He then translated this narrative into Spanish, along the way likely modifying or adapting aspects to make it better fit the Catholic project, and accompanying it with an essay about K’iche’ vocabulary, a missionary treatise, a translator’s prologue and annotations. The Popol Vuh, a mythical Indigenous work, thus became through Ximénez a part of the Church’s evangelical project.

As the scholar Néstor Quiroa argues, Ximénez formed part of a project to ‘extirpate’ the Maya-K’iche’ religion, and quotes a phrase by Fray Antonio de Remesal, the official chronicler of the Dominican Order: ‘Ut prius evellant de inde plantent’, or ‘First uproot and then plant.’ (As any gardener knows, let it be said, pulling up a root to plant something else is a physical act needing more than the vaunted ‘reason’ of the Dominicans.) Early evangelisation efforts had suggested a possible parallel or synthesis between Maya theology and Catholicism, equating Tz’aqol-B’itol and God but, when Ximénez wrote, this was no longer common practice. Early 18th-century Catholics generally considered the human as superior to the Indigenous person, and the Indigenous as slightly superior to the animal.

These projects involve what people now call ‘bias’, yet through them Indigenous traditions were preserved

Yet in Ximénez’s manuscript, the first thing that leaps to the eye is the double-column format of K’iche’ and Spanish, which physically locates the two linguistic and cultural traditions beside one other. In practice, of course, this was not the case, as it was a Spanish priest who compiled the manuscript and interpreted the material. The format does evoke a possible utopia of cultural comparison, however, in which cultures are in dialogue as equals. Even if it did not occur within history, here is a potent missed encounter between two rich belief systems, Mayan cosmology and Catholic theology.

There is still work to do in building a comparative framework capable of putting these traditions and cosmologies – with their internal critiques and doubts – into dialogue. Comparative literature and history are vital as humans continue to ask questions about the relevance of the nonhuman world within a narrative of technological progress, in an increasingly global context. Traditions need to be studied side by side rather than morally reduced to coloniser and colonised, or bracketed into distant departments. Like linguists in other parts of Latin America, such as Rodolfo Lenz who in 1905-10 compiled an Araucanian dictionary in Chile, or Antonio Ruiz de Montoya who in the 1630s and ’40s compiled a Guaraní dictionary in Paraguay, Dominican Ximénez’s work with languages forms part of the European colonisation of Mesoamerica. These projects involve what people now call ‘bias’, yet through them Indigenous traditions were preserved.

And here the animal returns in all its growling, strutting, buzzing, roaring magnificence. Today, many agree that the challenge is how to build a sustainable coexistence with forms of nonhuman life ranging from plants to viruses. Our relationship with nature can involve violence and inequality, but also balance, empathy, reciprocity and cyclical thinking. Animals, as they appear in works from Aristotle to the Atharvaveda to Arendt, have always been at the foundation of politics, because the category seems to both include and not include us humans.

An inescapably hybrid, palimpsestic product of the Mayan and Spanish Dominican cultures, the Popol Vuh provides a nuanced genealogy of the changing relationship between the animal, human and divine worlds, and recuperates a fluid movement between them. It explores alternatives to Enlightenment reason starting not from a humanism linked to nationhood and human rights, but from a cosmological sense of belonging to multiple forms of being and a planetary thinking that draws on universals other than capitalism. A true book of community and layered act of imagination, the Popol Vuh continues to challenge single authorship, cultural isolation and human dominance.