Listen to this essay

19 minute listen

What came first, the chicken or the egg? Perhaps a silly conundrum already solved by Darwinian biology. But nature has supplied us with a real version of this puzzle: black holes. Within these cosmic objects, the extreme warping of spacetime brings past and future together, making it hard to tell what came first. Black holes also blur the distinction between matter and energy, fusing them into a single entity. In this sense, they also warp our everyday intuitions about space, time and causality, making them both chicken and egg at once.

Physicists like me have long since accepted these strange properties of black holes. But I suspect that nature could very well have played a different trick altogether, and made black holes a gateway to something far more unusual – a region where the rules of spacetime themselves transform into something we’ve never seen before. Many objects we think of as black holes may, in fact, be imposters: identical on the outside but harbouring entirely different physics within. Finding out whether that’s true will require peeling back the shell of reality itself. And humankind is getting closer to doing exactly that.

To understand why black holes may be hiding something, let’s first recap how gravity works, because it is the foundation of how spacetime can curve itself into such exciting and mysterious objects. Before Albert Einstein’s theories, gravity had various unexplained features. Isaac Newton’s gravity states that the planets feel the Sun through the vacuum of space with no interaction whatsoever. What’s more, it also states that any interaction takes zero time. If we were to remove the Sun with the flick of a wand, Newton’s gravity suggests the planets would immediately be stripped from the Sun’s gravitational pull, contradicting the well-known fact that nothing travels faster than light.

It was Einstein who found the solution to this puzzle. All he needed was the simplest of observations: all objects drop in exactly the same way under the pull of gravity. Lift up a bowling ball in one hand and a cauliflower in the other, and you notice that one arm is struggling more. Yet, when dropped, both bowling ball and cauliflower fall equally fast and hit the floor at the same moment. Whatever difference there was in mass, gravity nullifies it on the way down. This reveals something very deep about nature. Just like the train tracks’ curves make every train follow the same twists and turns, the fact that the gravitational motion of all objects is the same reveals that this too must be due to curves, this time in space itself.

Around a star of sufficiently packed mass and energy, time gets squeezed into a single moment

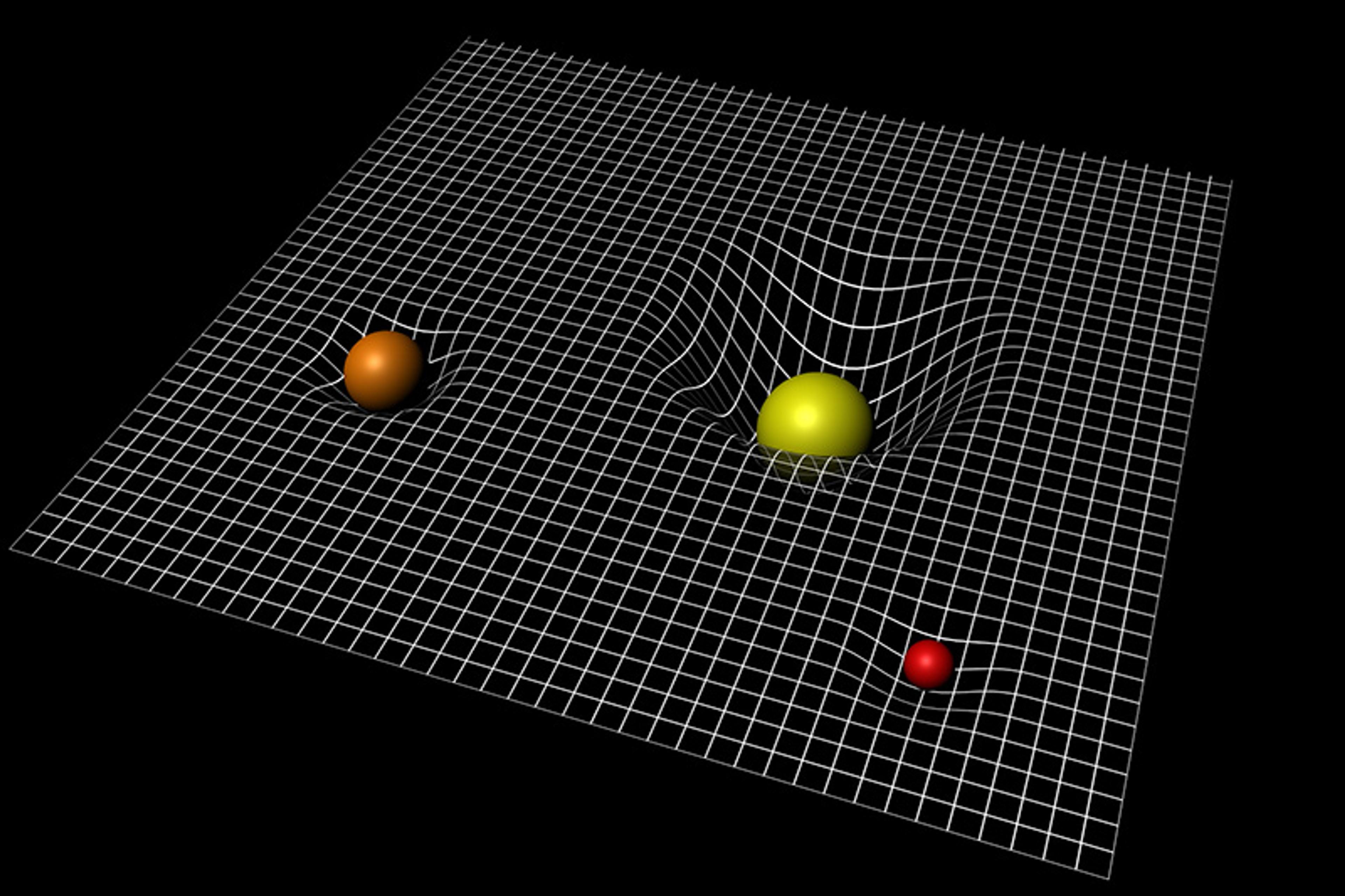

Thousands of experiments have since revealed that space and time are indeed a tapestry of curves, dents and stretches, invisible to the naked eye but fully measurable by the motion of planets, galaxies and even light. This is now as well established as photosynthesis, the existence of Mars, and that omelettes are made up of atoms. The Sun and planets, therefore, are connected by the curved spacetime between them – and any change in curvature must travel through this stretched fabric at the same universal speed limit as everything else. So, if the Sun did instantly disappear, Earth would continue orbiting the space it left behind for around eight minutes.

A European Space Agency artist’s interpretation of spacetime depicted as a simplified, two-dimensional surface, which is being distorted by the presence of three massive bodies, represented as coloured spheres. The distortion caused by each sphere is proportional to its mass. Courtesy ESA/C Carreau

Is Einstein’s the only way that space and time can be curved, though? One place to look for an answer is a black hole. It was soon realised that Einstein’s version of the warping of space and time came with a prediction: that around a star of sufficiently packed mass and energy, these train tracks become infinitely stretched, and time gets squeezed into a single moment, erasing all differences between earlier, now and later. These are the famous black hole solutions of Einstein’s general theory of relativity: spherical shells of pure curved spacetime, called horizons, floating in the vastness of the Universe. Any signal that finds itself having to walk an infinite amount of distance, and with zero seconds to do it, is certain to never make it out again. With no light, no matter and no radiation coming out from beyond the horizon, black holes are as black as black comes.

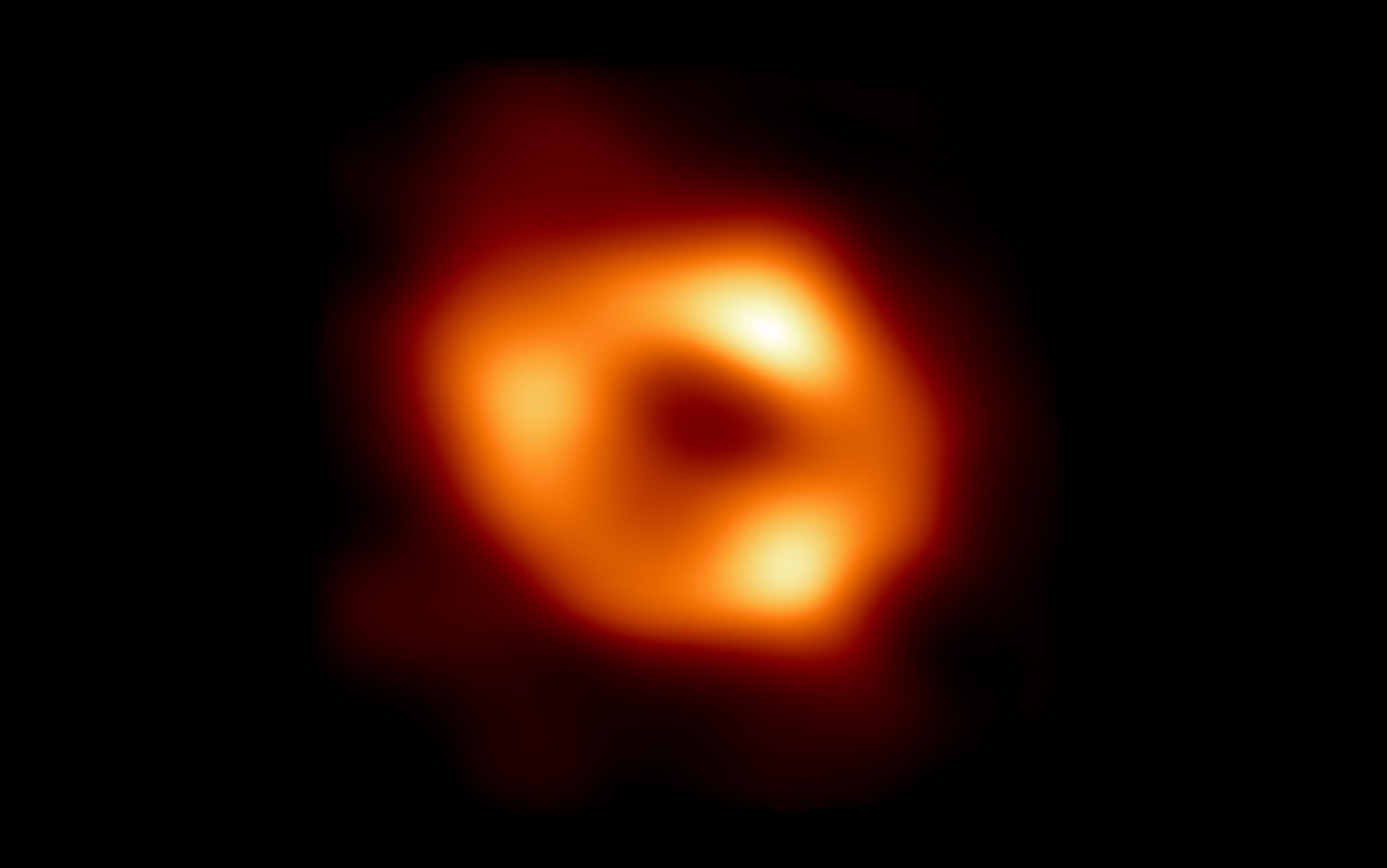

Black holes have been measured in spades, with different methods. One way has been by observing shiny stars orbiting a dark spot of nothingness where there should be a source of gravity (leading to a Nobel Prize in 2020). Another is by the gravitational waves from colliding black holes, which have been registered in the hundreds by the LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA detectors (also good for a Nobel Prize, in 2017). A third has been by the measurement of a ring of light whose paths are curved around a black hole (by the Event Horizon Telescope; a Nobel Prize might be pending there, too). Black holes really, truly, genuinely exist, telling us that Einstein’s curving of space and time must indeed be correct.

There is still, however, much that is unknown about black holes. It’s well established that their contents are mysterious and inaccessible, but unanswered questions also remain about their origins and evolution.

To see why, let’s go back to the chicken-and-egg conundrum: what came first, the chicken or the egg? In biology, the answer is given by Darwinian evolution, which lines up millions of generations of chickens and eggs along the arrow of time, each ever so slightly different from the previous generation. Tracing this line all the way back to find whether there is a chicken or an egg waiting at the starting point results in finding something that is a great-great-great ancestor who resembles neither.

A similar question can be asked about black holes. At their horizon, past and future are squeezed into a single moment, making it difficult to trace their ancestry. But that’s not to say black holes don’t have a beginning. For many black holes, the ancestor at the start of their chicken-and-egg line is a cloud of mass that cannot withstand its own gravity. In the 1930s, the physicists Hartland Snyder and J Robert Oppenheimer showed that if such a cloud of mass is left under the gravitational pull of its own constituent particles, it has no choice but to collapse onto itself. Gravity there works as its own flywheel, as the particles falling closer and closer to each other create more and more curvature that in turn makes the cloud of mass pull on itself more and more. Before long, a horizon will have formed, behind which everything inside will have disappeared, and no one from the outside will be able to see its ultimate fate. Stars are typical examples. As long as their internal furnace is burning hot still, its infernal heat pushes back against gravity, keeping the collapse in check. When the fuel runs out, gravity wins over, and Snyder and Oppenheimer’s prediction makes the star suck itself into literal oblivion. Seminal work by the physicists Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking showed that this final stop of cosmic evolution is quite inescapable.

One of the most striking properties of a wave is the impossibility to pinpoint its exact position

But what if there are other evolutions? Einstein’s formulas predict that the spacetime around a black hole is the same as that of any other spherical ball of mass, so it stands to reason that, maybe, the chain of chickens and eggs might have a different starting point, an ancestor not yet discovered, which might result in the same spacetime curvature as a black hole has but that harbours something else within the horizon. If they exist, these black hole ‘mimickers’ would be very interesting, revealing unknown physics. Maybe they are the result of existing rules not yet fully worked out, but they might also mean that the laws of physics themselves are new altogether, a new logic of space and time hiding behind the horizon.

An example of the first is the idea that literal nothingness collapses onto itself. Surprisingly, this is perfectly allowed when you sprinkle a dash of quantum mechanics over the early Universe. Quantum mechanics states that, if you zoom in enough, nature presents particles as little waves. One of the most striking properties of a wave is the impossibility to pinpoint its exact position; waves definitionally always stretch out over some distance, and this directly translates to the impossibility of exactly knowing the position of small particles. Radioactivity is a clear example of this: with nature not being clear on the location of the particles that make up an atomic nucleus, some of them might find themselves waving outside the atom, flying out in what we perceive as radioactive radiation.

Run back the clock on an expanding Universe and you will find it small enough for its quantum waviness to present itself. The waves of this early soup could have allowed it to randomly get just a little more energy in one position than another, potentially enough to create a horizon without there ever having been a star to begin with. The ultimate chickenless egg, laid instead from the quantum randomness of the early Universe. These primordial black holes are actively sought by gravitational wave detectors.

Quantum mechanics also allows a second example of a black hole mimicker. Close to the horizon of a black hole, space stretches enough that even tiny quantum waves become sufficiently large to rear their heads. The exact details of how this might happen are not yet fully understood (a complete theory of quantum gravity is still pending), but one prediction of quantum mechanics near black holes is that the horizon can form a layer of material, a shell around the black hole that prevents some signals from getting sucked in and, instead, get reflected back into the Universe.

And then there is that second scenario where the rules for curvature themselves change altogether, an area that I myself like to play in. Einstein’s theory of gravity hinges on the observation that all matter and energy fall the same under spacetime’s dents and tracks, but there is more than one way that this can be translated into mathematics, allowing in principle for a whole slew of spacetime behaviours that are different from Einstein’s original implementation.

One example are gravastars, a theoretical construct that fills up the inside of a black hole with some stuff that, unlike normal material that pulls on itself by gravity, instead pushes itself outward. Such mysterious material has been theorised for decades, due to the fact that the Universe has been measured to speed up its expansion via dark energy (another discovery that led to a Nobel Prize, this time in 2011). Supposing that this dark energy exists, filling up a black hole with it produces a new type of star whose gravitational tendency for matter to tug on itself is counterbalanced by its filling with a kind of anti-gravity. This results in a stable equilibrium of a perfectly spherical bubble of dark energy that looks, but is not quite the same as, black holes.

I myself am interested in a different scenario still. What if it is not the stuffing of the mimicker that plays by different rules of physics, but spacetime itself? The starting point of this investigation comes from one of the core principles of nature: its indifference from the observer looking at her. To explain this point, ask a friend what meal they like best. Next, start running alongside them, and ask again. Will their foodie preference be any different now? Of course not. Their taste buds do not care about the relative velocity between the both of you. Whether you are standing still relative to your friend or not, their love for pizza, omelettes, cauliflowers or whatever will come out the same, always.

The same idea holds for nature in her totality: her rules should be the same regardless of the motion of the observer. This is called the principle of relativity, one of physics’ most shiny gems. As far as we know, all of reality plays by this principle of being completely indifferent to the observer’s motion.

A more advanced example comes from electromagnetism. A charged particle like an electron has an electric field that informs other charged particles how they will be pulled or repelled. Next, look at that same electron while it moves with respect to you, and it will look to you like a current, which can famously produce magnetic fields on top of their electric field. How much electric field and magnetic field you perceive while looking at the electron depends on your state of motion relative to the electron. Yet, if you take the combined effect of the two fields, this will result in the exact same amount of pushing and pulling, regardless of how you happen to be moving with respect to the electron.

It turns out that it is indeed mathematically possible to glue different spacetimes to each other

It was actually this particular example that Einstein used in 1905 to derive his theory of relativity. He assumed that the indifference of electromagnetism to the observer’s motion was not a happy coincidence of mathematics, but a rule of nature that transcends the details of any particular phenomenon, be they electric, magnetic, your friend’s tastebuds, or otherwise. As the one thing that is shared by all these phenomena is that they take place in space and in time, Einstein assumed that it must therefore be space and time themselves that conspire together to make the principle of relativity work. And he was right: we since know and can measure that, indeed, space shrinks and time stretches in well-defined unison, and always such that everything in nature comes out following the exact same rules regardless of the observer’s motion.

But it turns out that Einstein’s theory is not the only way the principle of relativity can be ensured, and that it also allows other conspiracies of space and time. These alternative versions of relativity theory come with wonderful properties that are similar, but not quite the same, as Einstein’s version. For instance, they can imbue spacetime with a tendency for space to push itself outward. If conventional gravity pulls everything together, whereas this new type of spacetime pushes itself outward, a stable configuration could be possible in which the pushing and pulling balance each other out. This would be a novel type of black hole mimicker, a spherical shell that has new rules of spacetime on the inside whereas the rest of the Universe outside plays by conventional relativity theory. The subtle point is what happens on the shell where the two different spacetimes transition into each other. There, the curvature must have a smooth transition from the inside to the outer. This smoothness must necessarily be the case, because a black hole’s curvature is inseparable from its mass and energy, meaning that a jump in spacetime curvature would violate the conservation of energy, one of nature’s other sacred principles.

It turns out that it is indeed mathematically possible to glue different spacetimes to each other in this way, provided that the transition takes place exactly at the horizon of a black hole. This makes for yet another tantalising type of black hole mimicker, where its horizon does not trap exotic stuffing, but is a gateway to other types of spacetimes. The fact that they would be hiding behind a black hole’s horizon would then conveniently explain why they have not been seen – at least so far.

There exist many models for black hole mimickers, worked out in beautiful mathematics. But is mathematical consistency enough to take their existence seriously? The history of science provides some clues here. When the standard black holes were predicted, they were originally seen as some sort of anomaly; an interesting product of mathematics, but not quite as real as atoms, egg-laying chickens, or the existence of a landmass called Great Britain. Sometimes scribbly symbols on a chalkboard simply predict more than nature has chosen to manifest. But in other cases, mathematics has been a very effective way to predict new rules of nature, even when the predictions sounded very unfamiliar at first. When the physicist Paul Dirac merged quantum mechanics with special relativity, he found twice the amount of particles than were then known to exist. And, lo and behold, measurements revealed that these antiparticles do indeed exist.

To which type of mathematics do black holes mimickers belong? Einstein himself firmly believed that conventional black holes were of the first type: an interesting prediction that nature decided not to adopt. But a century of measurements – and gravitational waves in particular – have shown that black holes are abundant in the Universe. The same might very well be the case for the mimickers.

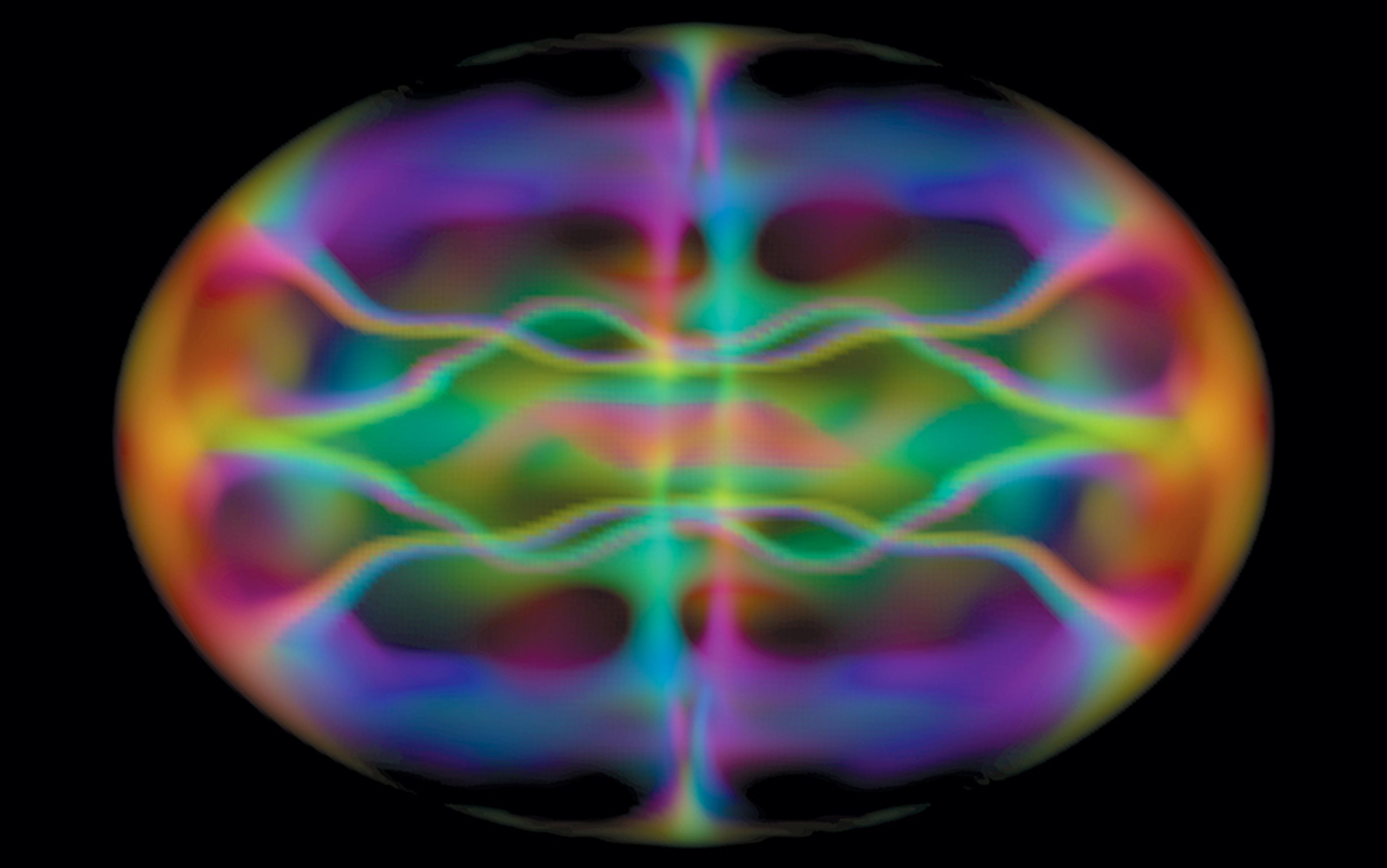

The way to find out is by actively going out and looking for them. Although it’s true that the outside spacetime of a black hole mimicker tends to look the same as that of a normal black hole and the inside is hidden from us by the horizon, their gravitational waves are likely to be different. Hit a black hole hard enough (crashing another black hole into it will do it) and it will wobble about, producing gravitational waves with very specific frequencies. Just as a chemist can identify the type of gas by the light frequencies it sends out, wobbly black holes have their own characteristic frequency spectrum that might allow us to separate black holes from the imposters. Fortunately, nature was kind enough to fill up the Universe with many such cosmic collisions. The only thing we have to do is measure their resulting gravitational waves in full detail.

Humankind is very close to unlocking such measurements. Black hole collisions have been measured in abundance in the past 10 years. And, as recently as this year, the gravitational wave detector network LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA was able to measure a black hole collision with such precision that the frequency spectrum of its wobbly end product could be seen. What’s more, the current network is soon to be superseded by the next generation of detectors, such as the upcoming Einstein Telescope and the LISA gravitational wave detector in outer space, which are much more sensitive to the frequencies of black hole horizons. With such powerful new techniques in hand, we might perhaps be able to crack the horizons of the black hole, or certainly peel at its shell. Whatever we will see, it is either going to tell us that black holes are exactly as we always expected, or will change our ideas of space and time forever.