In 1970, Paolo Soleri set out to build a utopia in the barren desert of Arizona. The Italian architect’s sojourn in the wilderness was an unusual one. Born in 1919 and educated at Turin’s renowned Polytechnic University, where he received the highest honours in architecture, Soleri moved to Arizona in 1947 to apprentice under Frank Lloyd Wright at the legendary architect’s home and educational centre, Taliesin West. Soleri spent a year and a half in Arizona and in Wisconsin before returning to Italy in 1950 to construct a massive ceramics factory in Vietri on the Amalfi coast, gaining international recognition for his innovative designs and masterful production of ceramic and bronze windbells.

Soleri fell for urban futurism during his first visit to the United States. Offended by the towering, inelegant skyline of Manhattan and the unchecked expansion of urban sprawl during the country’s post-war boom, Soleri envisioned cities that put people in a harmonious relationship with the natural world, and with each other.

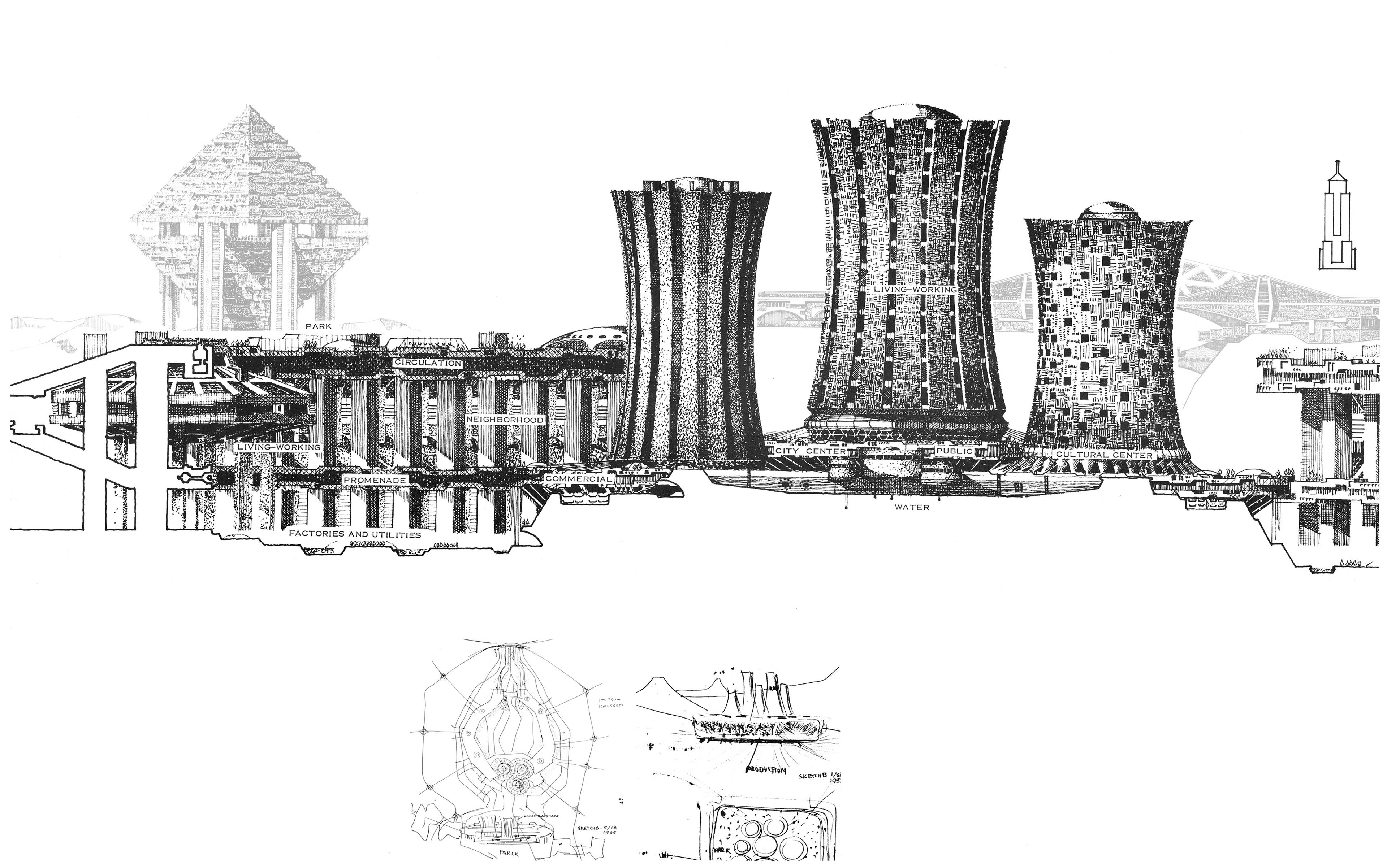

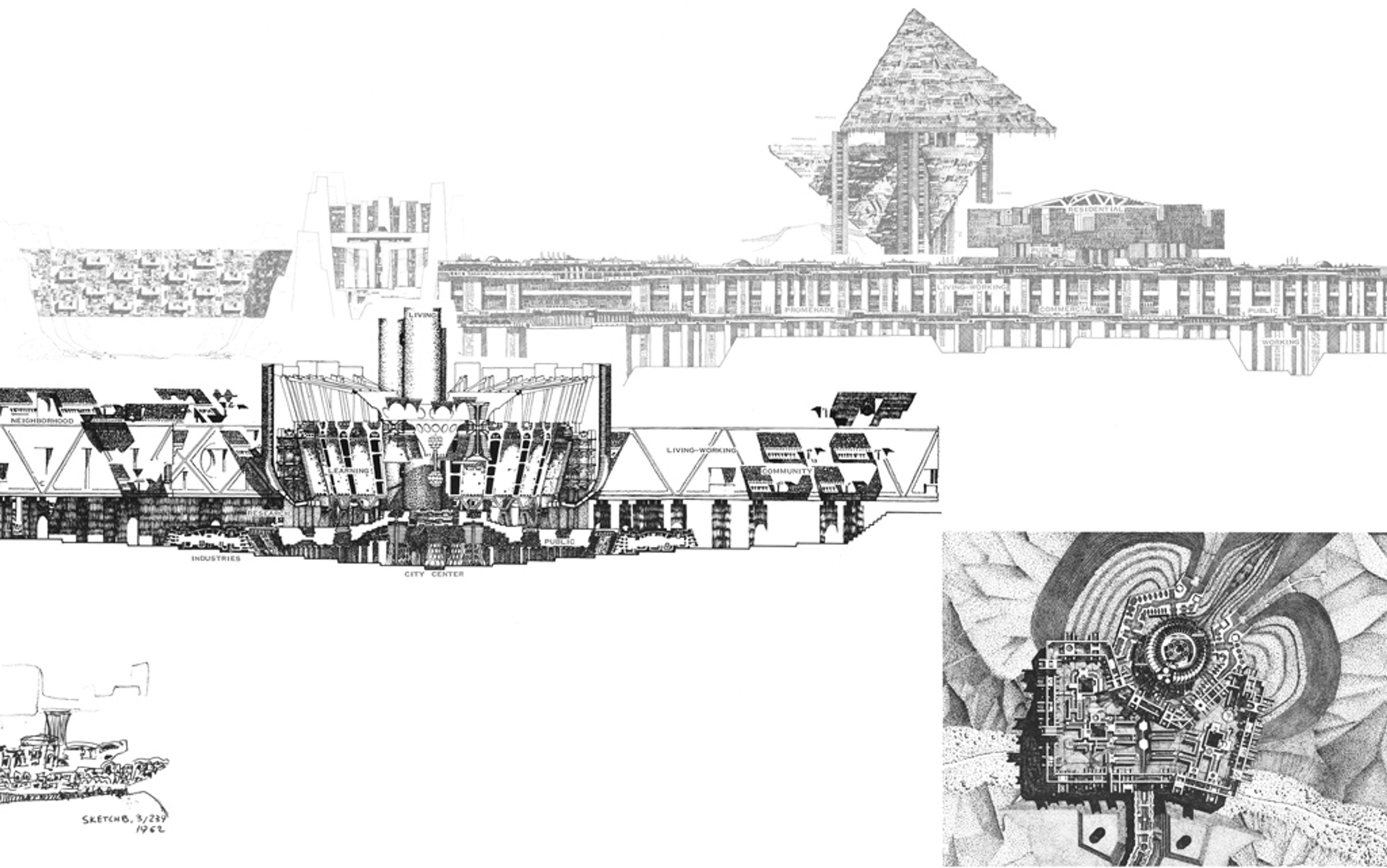

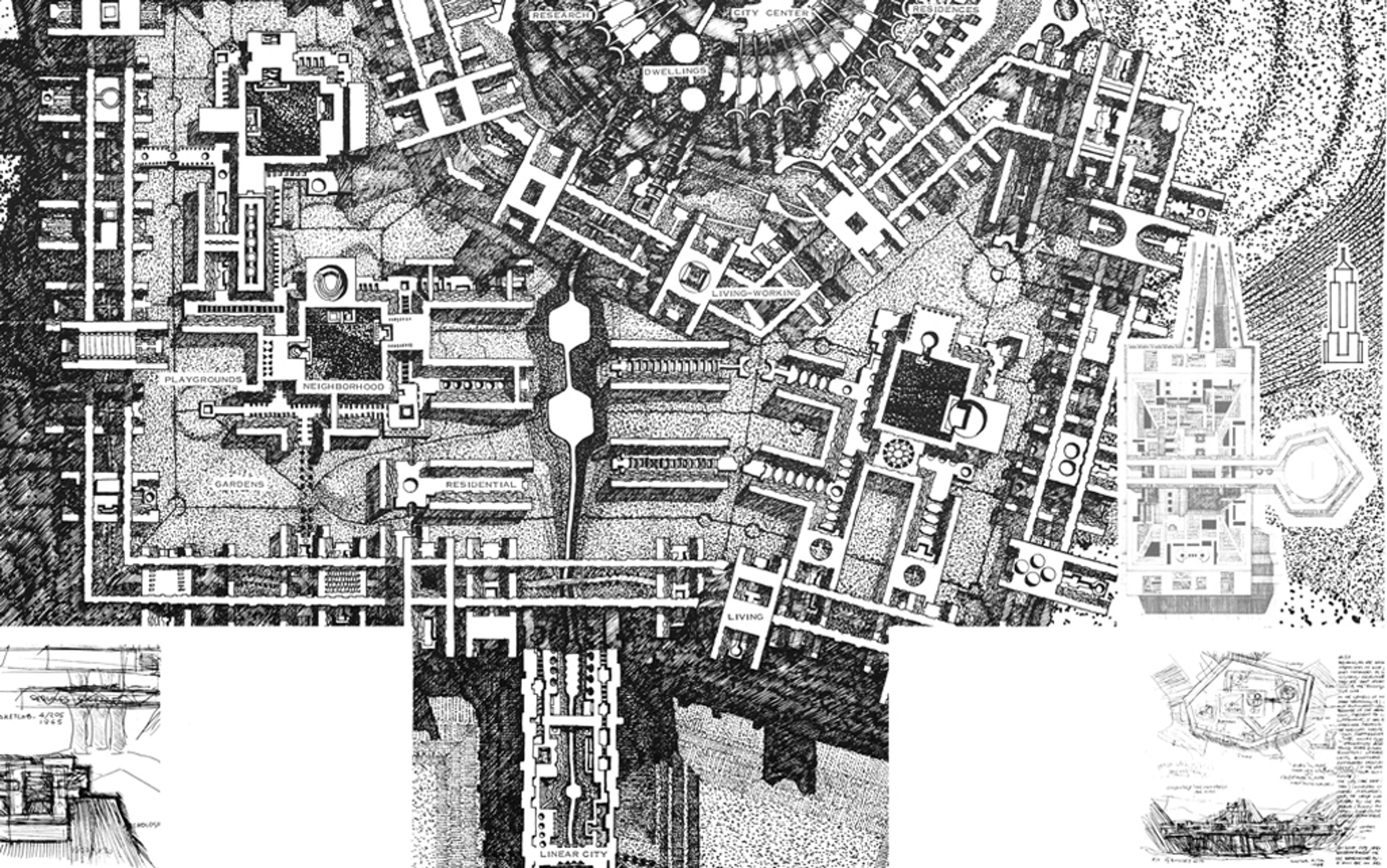

For Soleri, architecture and ecology were twin components of man’s relationship with nature – by treating cities as living, breathing, evolving organisms, humans could live in harmony with nature and with each other. He dubbed his defining philosophy arcology, a portmanteau of ‘architecture’ and ‘ecology’. ‘Architecture is the physical form of the ecology of the human, the configuration of matter which allows for the best energetic and willful flux,’ Soleri wrote in Arcology: City in the Image of Man (1969), his landmark exposition of his architectural philosophy.

Today, Soleri’s fingerprints are everywhere in our template of the cities of tomorrow. Soleri’s principles of sustainable, hyper-efficient buildings engineered to facilitate evolving human communities have become ingrained not just in the architectural community, but in our collective vision of humanity’s future.

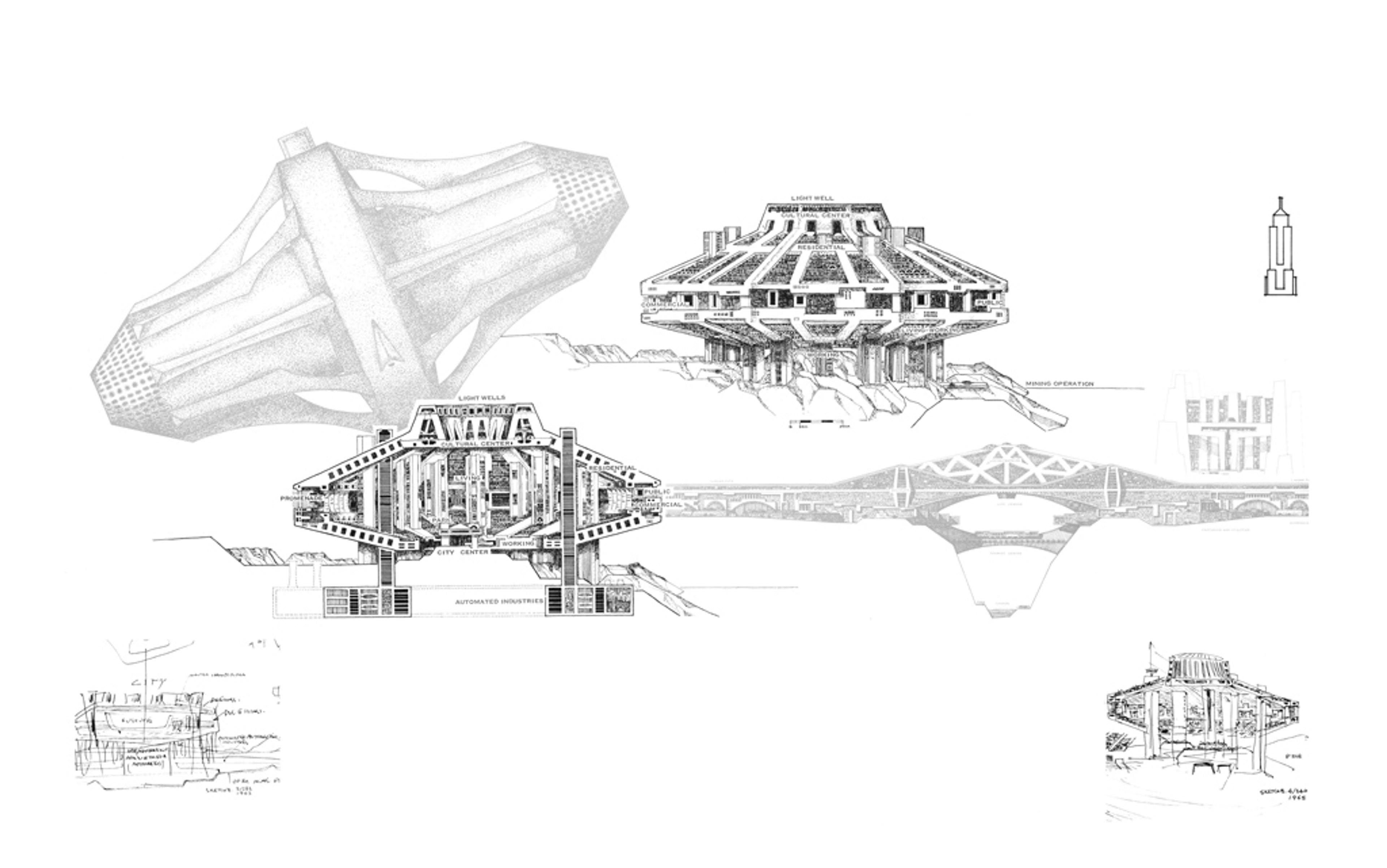

Arcologies are represented in contemporary culture by towering buildings with their own unique ecological environs, or in science fiction, with its self-contained space stations or hulking mega-structures. Arcologies are littered throughout the work of esteemed science‑fiction authors such as Frank Herbert, William Gibson, Isaac Asimov and Larry Niven. The massive Cooper Station in the space drama Interstellar (2014) bears the hallmark complexity, density and efficiency of conventional arcology. And in SimCity 2000, the popular city-building game, arcologies appear as late-stage futuristic mini-cities contained in a single building; construct enough of one variety, and the buildings blast off into outer space in search of distant planets to colonise, just as Soleri envisioned.

But while sci-fi writers and futurists imagined the triumphant metropolises of the not-so-distant future, Soleri set off to the Arizona desert to actually build one. Soleri wanted to answer a simple question: is it possible to design a utopia? Can the perfect human habitat be engineered by human hands, or does it have to emerge, organically, from the ecological and economic forces far beyond the grasp of a master builder? Soleri would spend the rest of his life trying to find out.

In 1956, Soleri and his wife Corolyn ‘Colly’ Woods moved just miles from Phoenix’s out-of-control suburban sprawl to set up an architectural workshop, dubbed Cosanti (from the Italian cosa and anti, or ‘before things’), in Paradise Valley to develop his unique philosophy of architecture. One of Soleri’s earliest visions was Mesa City, a proposed city the size of Manhattan with 2 million inhabitants. Over five years, Soleri would draw hundreds of feet of scrolls detailing the intricate structures and landscape of this hypothetical metropolis.

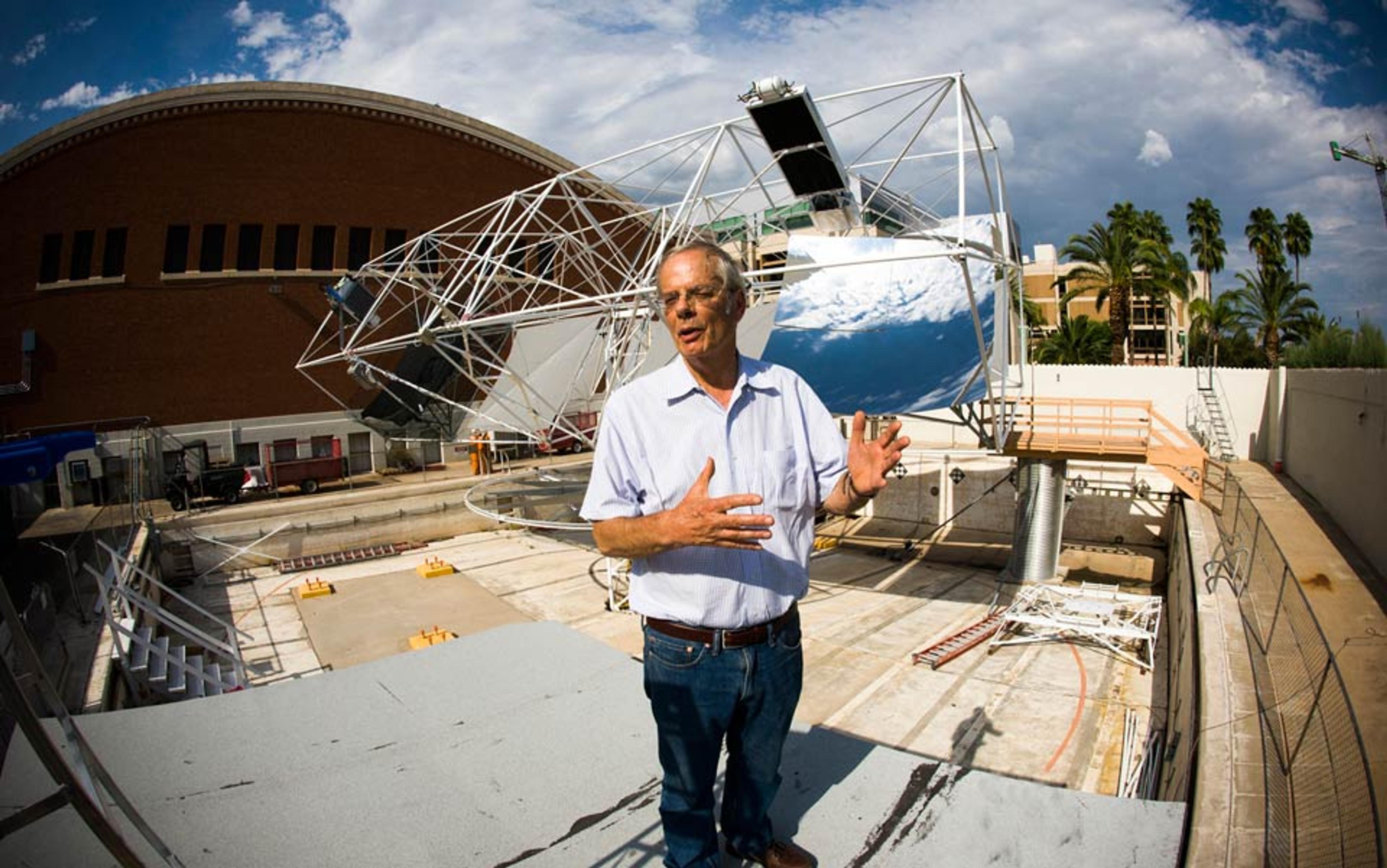

In 1970, Soleri finally broke ground on Arcosanti, an experimental city and ‘urban laboratory’ that has been under construction for nearly half a century. To the average visitor, Arcosanti looks like a college campus sprouting in the middle of the desert, molded from the red silt of the surrounding mesa. The complex is marked by a cluster of soaring stone apses, crafted in Soleri’s distinct, casting-inspired architectural style, designed to absorb sunlight and power the town’s energy grid. The majority of buildings are oriented to the south to capture the sun’s light and heat, while an open roof design yields maximum sunlight in the winter and shade in the summer. Artisans live and work in a densely packed compound, designed for maximum energy efficiency and sustainability. The community’s permanent residents keep greenhouses and agricultural fields, and income from bell-casting goes to maintaining the town’s infrastructure.

‘Arcology reorganises the sprawling urban landscape into dense, integrated, three-dimensional cities to support the complex activities that sustain human culture’

Arcosanti is as socially efficient as it is sustainable. The buildings and walkways are built in a more dynamic formation than a conventional city grid, not just to conserve resources but also to encourage increased social interaction between residents, forcing them to bump into each other in various open-air atriums, gardens and greenhouses. Living quarters are clustered in a honeycomb of sparse, minimalist apartments, all virtually identical. The open design and emphasis on sustainable living has created a distinctly hippy, communitarian vibe; the population of the town is mostly Soleri fanatics and bell-casting artisans. The city has never been officially finished, and while the current population wavers around 80, the town was designed to sustain some 5,000.

In some ways, Soleri defined his vision of arcologies in direct contrast to the work of modern urban planners such as Robert Moses, whose contributions to New York’s urban sprawl before and after the Second World War are often criticised as ‘preferring automobiles to people’. ‘Arcology,’ wrote Soleri in Earth’s Answer (1977), ‘recognises the necessity of the radical reorganisation of the sprawling urban landscape into dense, integrated, three-dimensional cities in order to support the complex activities that sustain human culture.’

With its soaring concrete apses and vibrant, welcoming bell-casting community, Arcosanti doesn’t necessarily capture the futurism of Soleri’s more ambitious and intricate designs in Arcology. But Arcosanti is a living argument that the idea of a city can continue to evolve and improve without wreaking fresh havoc on the planet’s already-scarred ecosystem, so long as such a guiding hand as Soleri’s can midwife its development.

Despite Soleri’s best efforts, it’s not clear that humanity is ready for the perfect architectural utopias he imagined. In 2004, Japan’s Shimizu Corporation proposed a modern arcology project ripped from the pages of Arcology with the TRY 2004 Mega-City Pyramid, a massive structure situated over Tokyo Bay. Built on five enormous trusses, it would have been more than 12 times as high as the Great Pyramid of Giza, and its ‘city in the air’ design of soaring glass windows would filter wind and sunlight for an estimated 1 million residents.

While originally proposed as an antidote to Tokyo’s ever-expanding urban landscape, the Shimizu Mega-City Pyramid is so large it simply can’t be built with current conventional materials. The Shimizu Corporation likely knew this: the design relies on the future availability of super-strong lightweight materials based on carbon nanotubes presently being researched, making the project little more than a futuristic PR stunt.

Russia’s Crystal Island is a similar disappointment. Proposed in 2003 for Moscow’s exurbs, the ‘city inside a building’ designed by Norman Foster was meant to soar almost 460 metres into the sky and house up to 30,000 residents, containing ‘more floor space than any other structure on Earth’. The project, like the Mega-City Pyramid, is less an exercise in arcology and more a commercial venture: the Mall of America on steroids. Architects at Foster and Partners said the plans called for some 900 apartments and 3,000 hotel rooms, and would include an international school for hundreds of students, a cinema, a museum and a sports complex, along with a bevy of stores. Despite a planned construction timeline laid out by Foster and Partners, the project was postponed in 2009 due to the global economic crisis. Its construction appears increasingly unlikely.

capitalism might be a more flexible force for innovation than the heavy-handed planning of futurists and architects

Compared with the brazen materialism of the Mega-City Pyramid and Crystal Island, Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City might be closer to Soleri’s arcology dream. Also designed by Foster and Partners, the 1,200-acre city was envisioned as a clean technology hub, relying completely on solar and other renewable energy sources and providing industrial and research space for companies such as General Electric, Mitsubishi and Siemens. Like Arcosanti, Masdar was conceived more as an organic campus for human activity, designed to be friendly to bicyclists and pedestrians, and to encourage spontaneous social interaction. But while construction began in 2008 and the compound has actual tenants – including the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, a research university – development ground to a halt due to economic downturn, although architects project the city will be completed between 2020 and 2025.

Despite the promise of Masdar City’s futuristic campus, modern arcology projects fail to capture the utopian success of Soleri’s arcologies. There’s a relatively simple reason for this: even when urbanites fixate on the idea of the city as an urban laboratory, few aggressively planned cities in the history of mankind have actually experimented with their internal organisation in the way Soleri imagined, from infrastructure to housing. In reality, the forces of capitalism might be more flexible forces for innovation than the heavy-handed planning of futurists and architects. Even Arcosanti’s hippie communitarian campus has failed to evolve in the manner Soleri envisioned.

History is littered with the empty husks of planned communities. Consider the Soviet town of Magnitogorsk, which grew during the 1930s from a small mining town into a vast industrial centre as part of one of Josef Stalin’s five-year plans. ‘The tempo of construction was such that millions of men and women starved, froze and were brutalised through inhuman labour and incredible living conditions,’ the American author John Scott wrote in his book Behind the Urals (1942).

Magnitogorsk is not a historical aberration: we see shades of Soviet brutality in the modern factory towns sprouting up across modern-day China. The giant Foxconn plants that produce consumer goods such as the iPhone are essentially self-contained cities for low-wage workers, so destitute and miserable that they’ve devolved into rioting and a rash of suicides in the past several years.

Even when communities are planned around aspirational ideals of sustainability rather than as engines of economic growth, there are similar problems. Consider the former Oracle CEO Larry Ellison’s ambitious plan to transform the Pacific island of Lanai (97 per cent of which Ellison purchased in 2012) into the world’s first ‘economically viable, 100 per cent green community’. Despite his utopian intentions, The New York Times Magazine reported in 2014 that the island’s 32,000 inhabitants were wracked with anxiety over how Lanai’s community would adapt to Ellison terraforming their home. In an interview with the Times’s Jonathan Mooallem, the local schoolteacher Karen de Brum captured this anxiety perfectly: ‘At the end of the day, Mr Ellison can do what he wants. He asks for input but that’s like me asking for input on what to do with my backyard. I own my backyard.’

arcologies such as Masdar and Shimizu are mere facsimiles of our current urban existence in the trappings of science-fiction mega-cities

And this is the fundamental problem with planned communities, from company towns to modern arcologies: they often forget about the people who inhabit them.

This is certainly evident in the Shimizu Mega-City Pyramid and in Masdar City, which both replicate the grids and angles of contemporary Western cities instead of the sloping walkways and graceful apses that make Arcosanti feel like an organic community. And it’s painfully obvious in China’s factory towns and the top-down utopianism of Ellison’s Lanai project.

Where Soleri imagined the current manifestation of Arcosanti as one step in the habitat’s evolution, envisioning the community’s growth in pre-planned stages, arcologies such as Masdar and Shimizu are static, barren, mere facsimiles of our current urban existence in the trappings of science-fiction mega-cities.

Then again, it’s not as though Arcosanti itself is a perfect example of an arcology. It’s population has been stagnant for years. If arcology is the future of mankind, is it a mankind made up solely of bell-casters and ageing hippies? As communities grow and scale, can their specific design accommodate a sea of humanity? With every aspect of Arcosanti pre-planned, it’s hard to imagine the community hosting the human diversity of New York City, whatever the latter’s problems. Soleri and his followers were ready for a meticulously designed experimental community, but for the rest of us the noise and sprawl of modern cities is more conducive to community than the rigid planning of a design genius. ‘If you build it, they will come’ might sound nice, but it just doesn’t apply to the city of the future.

The past few years have posed a new problem for Arcosanti: can an urban laboratory persist without the guiding hands of its chief scientists? Soleri died in 2013, but Arcosanti’s construction continues, carried out by students and devotees of his teachings. To date, more than 7,000 students have participated in its construction, and more than 50,000 architecture enthusiasts visit the site each year. But alumni who return to Arcosanti to commemorate the passing of the ‘oracle of the desert’ fear that, without Soleri driving the project, it will become a forgotten relic of the 1970s environmentalist movement.

‘To survive, Arcosanti must find a way to draw new converts to Soleri’s ideas without the charisma of the man himself to depend on,’ wrote Kyle Chayka in Modern Painters magazine after attending Soleri’s funeral. ‘Another option open to the Cosanti Foundation is to turn Arcosanti into a kind of museum, a monument to the utopian idealism of the 1970s rather than a working example of it.’

It’s unclear what the future will hold for both Arcosanti and its philosophical descendants such as Masdar City. But no matter what it might turn out to be, Soleri has certainly fulfilled his role as the ‘oracle of the desert’, leaving a lasting imprint on everything from green architecture to science fiction.

If he were still alive today, Soleri would likely argue that his utopian dream of a thriving arcology isn’t just a brilliant theory, or a brilliant desert mirage – it’s the key to humanity’s survival. In the foreword to a 2006 edition of his landmark text Arcology, Soleri had harsh words for the next generation of politicians, architects and urban planners.

‘Can anyone imagine a frozen tundra or a scorching Sahara colonised by millions of hermitages, single homes?’ asks Soleri. ‘A nightmarish American Dream incapable of supporting any kind of dignified life, let alone the evolution of a civilisation. Is the exurban (ever-expanding suburban) metastasis a bejewelled dream? Of food and shelter, the two indispensable needs of life, shelter is the direct responsibility of planners; architects, urban planners, builders, developers, speculators, politicians, students … time to wake up!’