Perhaps the grandest tale of capitalist modernity is entitled ‘The Disenchantment of the World’. Crystallised in the work of Max Weber but eloquently anticipated by Karl Marx, the story goes something like this: before the advent of capitalism, people believed that the world was enchanted, pervaded by mysterious, incalculable forces that ruled and animated the cosmos. Gods, spirits and other supernatural beings infused the material world, anchoring the most sublime and ultimate values in the ontological architecture of the Universe. In premodern Europe, Catholic Christianity epitomised enchantment in its sacramental cosmology and rituals, in which matter could serve as a conduit or mediator of God’s immeasurable grace. But as Calvinism, science and especially capitalism eroded this sacramental worldview, matter became nothing more than dumb, inert and manipulable stuff, disenchanted raw material open to the discovery of scientists, the mastery of technicians, and the exploitation of merchants and industrialists. Discredited in the course of enlightenment, the enchanted cosmos either withered into historical oblivion or went into the exile of private belief in liberal democracies. As Marx put it, all that was solid melted into air, and the most heavenly ecstasies drowned in the icy water of egotistical calculation.

With slight variations, ‘The Disenchantment of the World’ is the orthodox account of the birth and denouement of modernity, certified not only by secular intellectuals but by the religious intelligentsia as well. In A Secular Age (2007), his leviathan survey of intellectual history, Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor gestured toward a possible recovery of the numinous at ‘the unquiet frontiers of modernity’: the poetry and philosophy of Romanticism, as well as the efflorescence of spiritualities that constitute ‘New Age’. The resurgence of religious fundamentalism throughout the world over the past two generations (even in societies where ‘disenchantment’ was supposed to have vanquished the company of the spirits) is not the only event that casts doubt on the veracity of the disenchantment thesis.

Since the 17th century, much modern history has provided good reasons to show that ‘disenchantment’ is more of a fable, a mythology that conceals the persistence of enchantment in ‘secular’ disguise. Capitalism, it turns out, might be modernity’s most beguiling form of enchantment, remaking the moral and ontological universe in its pecuniary image and likeness. For some of the dissenters from the disenchantment thesis, capitalism perverted the sacramental character of the world. As the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins declared with late-19th-century industrial squalor in mind, ‘the world is charged with the grandeur of God … There lives the dearest freshness deep down things’ – a trace of divine radiance ‘seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil’. Capitalist enterprise obscures and disfigures the graceful quintessence of the material world.

Weber and Marx themselves pointed, though inadvertently, to an alternative account of capitalism that suggests the tenacity of enchantment. At the conclusion of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), Weber announced the twilight of the spirits not with exhilaration but with dread: the disenchanted world, he feared, would degenerate into ‘mechanised petrification’, ruled by ‘specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart’, philistines who believe they’ve attained ‘a level of civilisation never before achieved’. Maybe, he wrote, ‘new prophets will arise’ to herald ‘a great rebirth of old ideas and ideals’. Indeed, Weber wrote in ‘Science as a Vocation’ (1919): ‘We live as did the ancients when their world was not yet disenchanted of its gods and demons,’ adding: ‘only we live in a different sense.’ Where the Christian God replaced the dying pagan deities, ‘we’ had no supreme beings in waiting. In the interim, ‘many old gods ascend from their graves’ and take ‘the form of impersonal forces’; Weber’s intuition that the gods had assumed a modern, ‘secular’ façade – especially in the ‘laws’ of the market that had acquired something like a divine status – suggests that the hegemonic version of ‘disenchantment’ is at least partly mistaken, if not fallacious.

Though renowned for describing religion as ‘the opium of the people’, Marx was emphatic that enchantment had also taken refuge in the capitalist marketplace. While in the Communist Manifesto (1848) Marx identified capitalism as driving disenchantment – immersing those ‘heavenly ecstasies’ in the gelid whirlpool of ‘egotistical calculation’ – he also referred to the capitalist as ‘a sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world he has called up by his spells’. Rhetorical flair, to be sure; but elsewhere – in his ‘1844 manuscripts’, and in the Grundrisse (1857) and Capital (1867) – Marx called attention to the enchantment of money and commodities under capitalism. Having drowned traditional religion, money morphed, he asserted, into ‘the almighty being’, ‘the god among commodities’, ‘the truly creative power’. This is more than literary grandiloquence; for Marx, money is, in effect, the ontological leaven and foundation of the capitalist world: ‘If I have the vocation for study but no money for it, I have no vocation for study – that is, no effective, no true vocation.’ (In economics, it’s called ‘effective demand’: if I’m thirsty but have no money for water, my thirst doesn’t exist.) Money is not just a medium of exchange; like the God who creates ex nihilo, out of nothing, it becomes the source and arbitrator of ontological validity under capitalism.

Marx expanded on the ontological sorcery of money when he wrote, in Capital, on commodity fetishism. The commodity, he writes, abounds in ‘metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties’. Those ‘subtleties’ and ‘niceties’ arise from the very nature of commodities themselves, divided between their ‘use-value’ – the qualitatively different purposes and uses of goods (shoes for feet, cups for drinking, etc) – and their ‘exchange-value’ – their status as commodities produced for sale to make money and accumulate capital. In order to be exchanged for money, an abstract equivalence among commodities must be established; their incommensurable use-values must be erased and their ‘value’ or ‘worth’ expressed in monetary terms. Thus – like the vocation whose effective existence depends on the size of one’s bank account – ‘value’ is not only assessed but determined in the ontological crucible of money. Money is what anthropologists might call the mana of capitalism: the spirit that inhabits all material things, and whose departure decrees oblivion. Purchase, sale and investment become acts of mercenary divination; Marx describes ‘all the magic and necromancy that surrounds the products of labour’. Commodity fetishism is the equivalent, in capitalism, of the Roman Catholic sacramental system: where the latter conveys divine power and grace through material objects and rituals, the former channels the power of money through the pecuniary transubstantiation of objects.

Marx expected revolution to dispel the venal alchemy of commodity fetishism, as political struggle against the power of money disenchanted the apparatus of fetishism. Simone Weil, the French mystic and radical, long ago offered an explanation for the continuing failure of Marxism to secure its Hollywood ending. Because it envisioned socialism as the dialectical culmination of capitalism, Marxism, in her words, represented ‘the highest spiritual expression of bourgeois society’. Weil observed that, like the industrial bourgeoisie and both its religious and secular ideologues, Marx and his followers subscribed to a disenchanted conception of matter. Marx might have considered his materialism ‘historical’, but if matter – even historical matter – is governed by the immutable and unyielding law of force, then on Marx’s own terms capitalism is insurmountable. Embedded in a disenchanted materialism, Marx’s trust in the forces of history required him to affirm dispossession, proletarianisation, the industrial division of labour, and the mounting concentration of economic and political power – a historical momentum that portended, not the demise, but the entrenchment of capitalist hegemony.

Weil rejected the Marxian theory of modern disenchantment on the grounds that it presumed an erroneous and truncated account of matter, one that rejected out of hand any possibility that matter could convey any spiritual import or power to historical action. The spiritual and material worlds did not, to Weil’s mind, constitute a dualism; they were complementary rather than antithetical or antagonistic, and the corporeal realm could mediate divinity while still structured by the laws of nature. Weil preferred an enchanted or sacramental materialism with its own social theory and political implications. ‘The true knowledge of social mechanics,’ she wrote in Oppression and Liberty (posthumous, 1955), involved a conviction that ‘there exist certain material conditions for the supernatural operation of the divine that is present on earth’. In other words, because matter was capable of conveying the supernatural, she saw Marx’s disenchanted materialism as, in a sense, not materialist enough. There is ‘a divine order of the universe’, Weil insisted, and the historical mediations of ‘labour, art and science are only different ways of entering into contact with it.’

Long before Weil, enchanted materialism found an exponent in Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the Diggers, the most radical of the movements that appeared during the English Revolution of the mid-17th century. A band of landless men who occupied and cultivated St George’s Hill outside London in the spring of 1649, the Diggers (or ‘True Levellers’ as they called themselves) called for common ownership of land and an end to enclosure – the eviction of farmers and the fencing of the commons, the first steps in what Marx called the ‘primitive accumulation’ that gave birth to capitalism.

Seeing many ‘cheated by false-spirited men’, Winstanley – in tracts he wrote from 1648 to 1652 – sketched an unorthodox theology of communism. He insisted that the nascent capitalist order was not just an injustice but a desecration. God, he thought, permeated all things in radical, panentheist immanence, vibrating and shimmering through the material world like Hopkins’s dearest freshness. ‘The whole creation … is the clothing of God,’ he avowed; He ‘fills all with himselfe, he is in all things, and by him all things consist.’ God, or ‘the Great Creator Reason’, had ‘made the Earth to be a Common Treasury’; ‘the Living Earth is the very Garden of Eden, wherein that Spirit of Love did walke.’ The world was charged with this spirit of Love, communism pulsed through the marrow of creation.

Winstanley envisioned a material version of the Christian fall from grace, whereby man began to ‘delight himselfe in the objects of the Creation, more than in the Spirit Reason and Righteousness’. The Fall into idolatry triggered the emergence of property, class and despotism – ‘civil propriety’, as Winstanley called it, with disdain. Greed induced a mis-enchantment of the world; ‘the Ayre and Earth is all poysoned, and the curse dwels in both.’ By occupying St George’s Hill, Winstanley and his comrades had commenced a crusade against the ‘disturbing devil’ of enclosure, or agrarian capitalism metastasising through the English countryside. Winstanley called for English men and women to revive the original communism and reclaim the common treasury of the holy earth. Imbued with the spirit of love, True Levellers would ‘restore all things from the curse’, building a beloved Eden of enchanted communards on the ruins of enclosure. (Alas, the curse remained. Driven from St George’s Hill and silenced in the wake of Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, Winstanley eventually joined the Society of Friends and became a respectable corn merchant in London.)

In his masterpiece The World Turned Upside Down (1972), the historian Christopher Hill tried to turn Winstanley into a proto-Marxist, arguing that his merger of God and ‘Reason’ indicated he was ‘struggling towards’ insights conveyed more credibly in ‘non-theological materialisms’. Yet there is no reason to characterise Winstanley in this way other than Hill’s own assumption that religion is an impediment to revolution. Winstanley’s sacramental sensibility galvanised him to political action and afforded him a keen discernment of the iniquity of capitalism.

The Romantics criticised industrial capitalism as a kind of demonic enchantment

Winstanley’s sacramental materialism found later exponents in the Romantic movement, which inherited the sacramental imagination from Christianity. Some of the best-known passages in Romantic poetry exhibit this sacramental quality: William Blake’s ‘auguries of innocence’ that enable him to perceive ‘Heaven in a Wild Flower’; William Wordsworth’s awareness of a ‘presence’ or a ‘sense sublime … Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, / And the round ocean, and the living air, / And the blue sky, and in the mind of man’. Romantics discerned this world of wonders through ‘imagination’ – a perceptual and rational as well as creative faculty, a kind of vision that enabled the visionary to see more keenly into reality. ‘How can we sing and paint when we do not yet believe and see?’ as Thomas Carlyle asked. Imagination was, Wordsworth explained, ‘reason in her most exalted mood’.

Relying on imagination, the Romantics criticised industrial capitalism as a kind of demonic enchantment. ‘Commercial nations, if they acknowledged the deity whom they serve, might call him All-Gold,’ wrote the poet Robert Southey; indeed, Mammon was ‘a more merciless fiend than Moloch’. ‘Rapine, avarice, expense / This is idolatry; and these we adore,’ Wordsworth wrote of mercantile London. In an early poem, ‘Mammon’, Blake confessed his attraction to the demon: ‘I took it to be the throne of God.’ Mammon was the owner and manager of the ‘dark Satanic mills’ that despoiled England’s green and pleasant land. Like Winstanley, Blake perceived cosmological defilement as well as venality in Lucifer’s factories, a contagion of ‘the spirit of evil in things heavenly’ that turned the world into a ‘Babylon … in the waste.’

In the second quarter of the 19th century – after the Luddite rebellion of the 1810s, the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, and the rapid acceleration of British industrial development – ‘Tory radicals’ such as Carlyle and John Ruskin translated the epiphanies of Diggers and Romantics into the new genre of social criticism. In Sartor Resartus (1833-34), Carlyle wrote of the need to re-tailor ‘the Mythus of the Christian Religion’; the gospel, he asserted, must be re-clothed ‘in a new Mythus, in a new vehicle and vesture, that our Souls … may live.’ Like Winstanley’s, Carlyle’s unorthodox gospel portrayed the world as both a source of sustenance and a portal onto divinity: ‘the Universe is an Oracle and Temple, as well as a Kitchen and Cattle-stall’. Yet there was an insidious new ‘mythus’ that stalked the world: ‘the Gospel of Mammonism’, as Carlyle decried it in Past and Present (1843), a counterfeit evangel proclaiming the ‘miraculous facilities’ enabled by money. Mammon’s gospel had rendered people ‘spell-bound’ in ‘horrid enchantment’; ‘invisible Enchantments’ suffused the ‘plethoric wealth’ churned out by the immiserating factories.

Carlyle’s friend Ruskin rooted his Romantic view of capitalism in a robust imagination of mercenary mis-enchantment. An art critic and historian, Ruskin was mostly known to his contemporaries as a prophet against industrialism: the second volume of The Stones of Venice (1851-3) brought us one of the earliest invectives against mechanisation, and Unto This Last (1862) – one of the greatest (and most vilified) artifacts of social criticism of the Victorian era – inspired not only the Arts and Crafts movement but trade union and Labour Party rank and file.

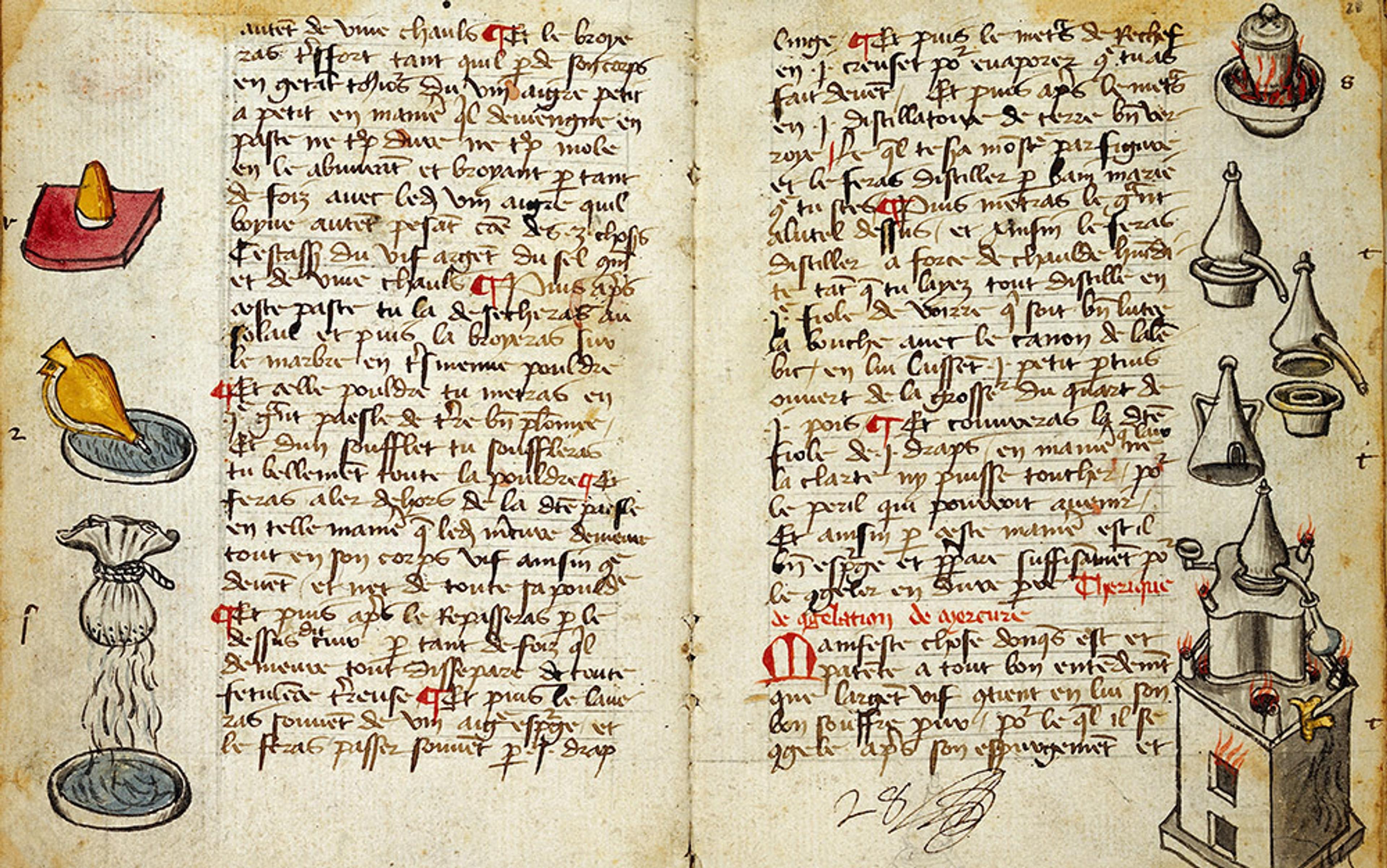

Marking the stark antagonism between the necessities of capitalist competition and Christian charity, Ruskin observed in Unto This Last that he ‘knew no previous instance in history of a nation’s establishing a systematic disobedience to the first principles of its professed religion’. Ruskin traced the national apostasy to a mis-enchantment that wrought human and ecological devastation. Throughout the five volumes of Modern Painters (1843-1860), he espoused a heterodox sacramental ontology and humanism, praising the ‘ceaseless, inconceivable, inexhaustible loveliness, which God has stamped upon all things’ – especially human beings, whose souls were ‘a mirror of the mind of God’. To Ruskin, capitalism violated earthly beatitude. Devoting their ‘Mammon-matins’ and ‘Mammon-vespers’ to ‘the Goddess of Getting-on’, capitalist societies, he remarked in The Political Economy of Art (1857), worshipped ‘the great evil Spirit of false and fond desire, or Covetousness, which is Idolatry’. (In Unto This Last, Ruskin compared economics to witchcraft and alchemy.) In The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884), Ruskin’s prescient account recorded the pervasive ecological despoliation of the ‘visible Heaven’ of the atmosphere: clouds infected by ‘bitterness and malice’, and the earth polluted into a hellscape of ‘Blanched sun, – blighted grass, – blinded man.’

From early 19th-century Transcendentalists to the 1960s counterculture, American thinkers have also spoken against capitalist mis-enchantment. Though alienated from organised Christianity, Henry David Thoreau possessed a vivid sense of the holy and sacred. ‘The earth I tread on,’ he wrote in his journals, ‘is a body – has a spirit – is organic – and fluid to the influence of its spirit …’ The market economy profaned the spirit he saw animating the earth. Condemning his pious and enterprising neighbours who lived near Walden Pond, Thoreau focused his fury on one devout yeoman in particular who worshipped ‘the infernal Plutus’. As the farmer was a devotee of pecuniary metaphysics, ‘fruits are not ripe for him till they are turned to dollars’.

With the development of American capitalism after the Civil War, a number of Populists, Social Gospelers, and Arts and Crafters continued the critical tradition of mis-enchantment. Ignatius Donnelly, a popular firebrand and autodidact, promoted a producerist cosmology that echoed Carlyle and Ruskin. The myriad forms of energy and matter were, he asserted, ‘God’s glorious stamp’ on creation; confounding this emblem of divinity, bankers idolising gold ensured the ‘survival of primeval superstition’.

Social Gospelers articulated a similar remonstrance in a more Christian idiom. George Herron spoke for many when he declared that material goods were ‘sacraments of grace’, and that labour and technology were media through which ‘God creates and unfolds the power of men’. If all material reality was sacramental – conveying the grace and power of God – then human making, rightly conceived and performed, was as legitimate a path to righteousness as the more ritualised forms of sacrament. Affirming this ontology, W D P Bliss claimed that George Pullman’s exploitative company town outside Chicago was ‘a devil’s sacrament’, a moral and metaphysical depravity. In Socialism and Character (1912), an important work of socialist theology, Vida Dutton Scudder avowed that ‘the material universe … is a sacrament ordained to convey spiritual life to us’. She contended that God is so present in nature and society ‘it is easy to confuse Him with the very world which He inspires’ – the idolatry into which capitalists fell, worshipping the creation rather than the creator.

Peter Burrowes, a representative voice of the Arts and Crafts intelligentsia, marvelled at craftsmanship in 1904 as ‘the sacrament of common things’, while Horace Traubel, another prominent practitioner, saw ‘God woven in tapestries and beaten in brasses and bound in the covers of books’. Industrial technology, they thought, dehumanised production and deprived men and women of sacramental agency; it posed, in Mary Ware Dennett’s view, ‘a religious problem’ as well as a social question.

‘The task of our generation … is one of metaphysical reconstruction’

William James also echoed Romantic anti-capitalism. In ‘On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings’ (1899), he lamented the ‘jaded and unquickened eye’ of disenchanted moderns, caught up in the scramble for riches. In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), James wrote of his alarm at the extent to which acquisitiveness had cancered ‘the very bone and marrow’ of his generation, and he offered ‘saintliness’ as the existential antidote to avarice. Saintliness, to James, was neither callow nor sanctimonious; the saint dwelled in a ‘rapture’ or ‘ontological wonder’ at the beauty and vastness of the Universe – ‘rapt’, he wrote, ‘to the mere spectacle of the world’s existence’.

These religious indictments of capitalism found, in the 1960s, a later generation of exponents. Of all the era’s Left-wing mystics – the Catholic monk Thomas Merton, the poets Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, among many others – it was Theodore Roszak in The Making of a Counter Culture (1969) who gave the richest and most cogent alternative to the myth of disenchantment. In Where the Wasteland Ends (1972), Roszak developed a more ambitious account of how radicals needed to enlist the wisdom of older, premodern beliefs, accentuating ‘visionary splendour and the experience of human communion’.

Pointing toward the Romantics, Roszak urged readers to take up the ‘battle cry of a new Reality Principle’: a ‘sacramental consciousness’ more vivid than its ‘objective’ (but not erroneous) antagonist. Politics, he admonished, ‘is metaphysically and psychologically grounded’ – our conceptions of the world and our place within it determine both how we structure communities and how we seek and allocate power. By reducing the world to inanimate stuff that could be understood and manipulated only by experts, ‘disenchantment’ or ‘objective consciousness’ served the interests of business and professional elites – ‘the technocracy’, in Roszak’s shorthand. It allowed them to establish what he called a deadly ‘monopoly of the sacramental powers’. ‘Disenchantment’ disempowered the people; but in organic farms, rural and city communes, cooperatives, free clinics and ‘open universities’, as well as in a mélange of genres and traditions – poetry, Gestalt psychology, Catholic mysticism, Hindu and Zen Buddhist spirituality, Native American animisms – Roszak saw the human and spiritual lineaments of a sacramental, ‘visionary commonwealth’. The restoration of a ‘sacramental vision of nature’ would discredit disenchantment and ‘the technocracy’, and usher in a more humane, democratic and green political economy. As one of Roszak’s visionary vanguard, the economist E F Schumacher, wrote in Small is Beautiful (1973), ‘the task of our generation … is one of metaphysical reconstruction.’

With ecological as well as economic calamity looming today, understanding and addressing the ontological assumptions of capitalist modernity is imperative. Indeed, ‘metaphysical reconstruction’ must lie at the basis of any revolutionary struggle in our day – in fact, it’s necessary for the survival of the species. If it’s long past time to deny that ‘there is no alternative’ to capitalism, the time has come to renounce the parochial secular dogma of ‘the disenchantment of the world’. The pre-modern belief in the enchantment of the world – modernised in Romanticism, blending scientific rationality with Hopkins’s conviction of God’s worldly grandeur – offers a more humane and generous account of our place in creation, and it provides the most compelling foundation for opposition to capitalism.