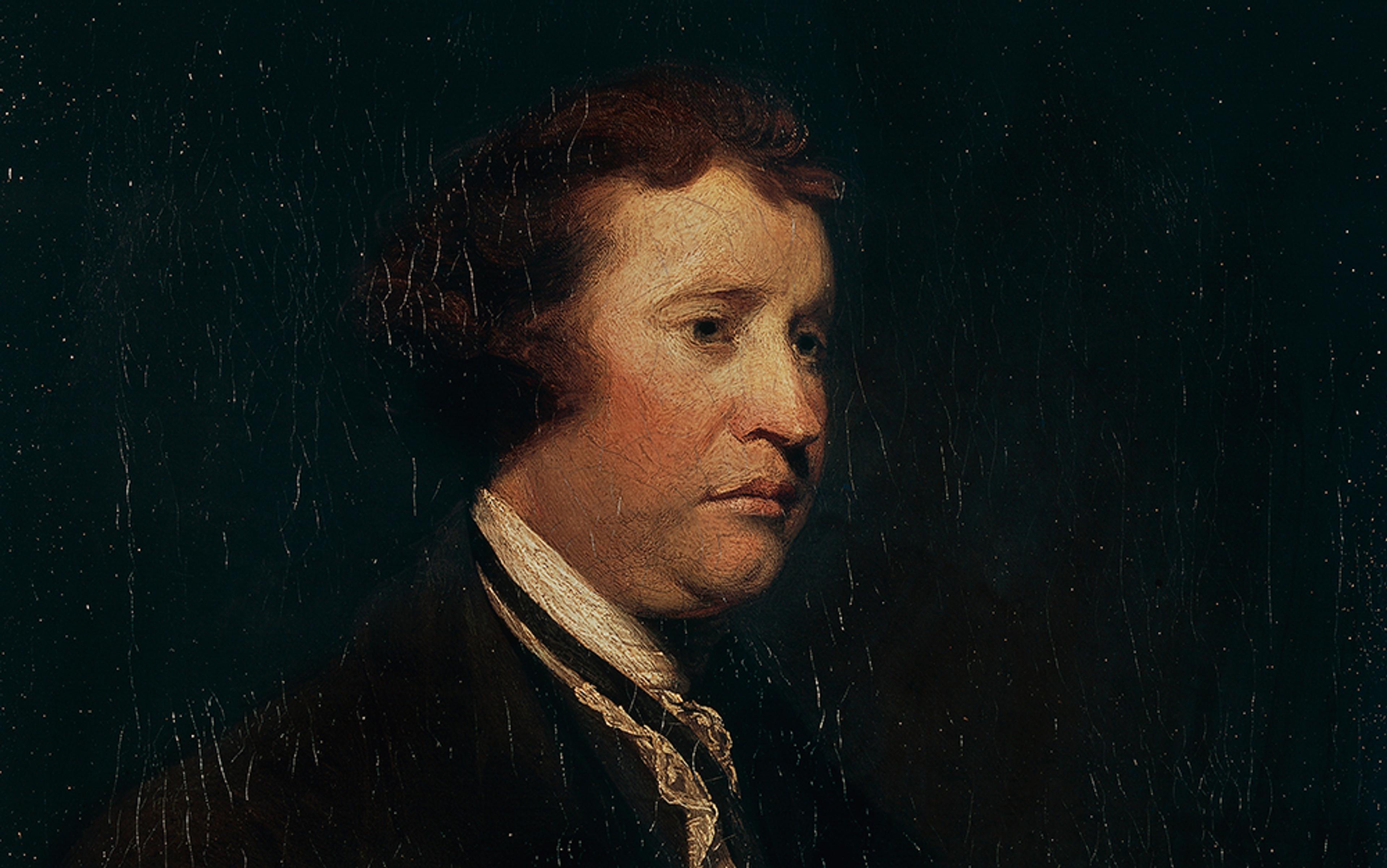

Edmund Burke, one of the great statesmen and philosophers of the 18th century, is the founder of modern conservatism. Or so it is commonly held: authorities, from Corey Robin on the left to Niall Ferguson on the right, agree that conservative ideology can be traced to this original source. The view has in fact been commonplace in the United States since the 1950s and has steadily been gaining currency across the globe. Admirers of Burke’s ‘traditionalism’ can be found in numerous countries, as different as the Netherlands and Japan. Yet there is something deeply misleading about this view of conservatism’s origins. Burke was a reforming Whig of the 18th-century British parliament whose ideas were not developed with modern politics in mind.

Even if we imagine Burke as our contemporary, his commitments are not in any way compatible with conservatism. For example, he was a defender of colonial rights against the British Empire during the period of the American Revolution. In lending his support to American defiance, he opposed the reigning tenets of British imperial policy and took a stand against successive ministries at Westminster. His defence of colonial rights included support for insurrection, for violent resistance against established authority. It is hard to reconcile this endorsement of revolt with what are usually regarded as conservative ideals.

Conservatives have either ignored Burke’s support for colonial rebellion, or maintained that his career was split between two phases: an early period of support for the ‘liberal’ cause of America and a later ‘conservative’ reaction to the Revolution in France. Burke certainly changed his opinions over the course of his career, but these shifts cannot be captured by presuming a contradiction between his support for American resistance and his aversion to the revolution in France. Representations of Burke as a renegade from early idealism are based on the dogmatic assumption that the American and French revolutions were fundamentally ‘the same’. Yet for Burke these two events were absolutely different, and in fact he had good reasons for insisting on their difference.

Burke’s interest in the North American colonies began in his 20s. Born in Ireland in January 1730, and educated in County Kildare and then at Trinity College Dublin, he moved to London in 1750 to study for the bar but was soon devoting his attention to assorted projects in the republic of letters.

From the mid-1750s, this ambition was combined with plans to get involved in public affairs. By the summer of 1757, America seemed an attractive destination for that purpose: on 10 August, Burke confided that he would soon (‘please God’) be crossing the Atlantic. The enterprise, however, never came to fruition, though Burke was still discussing it with friends as late as 1761. Yet before long, his personal interest in the colonies would be matched by his resolute intellectual engagement.

Other schemes in the interim absorbed Burke: he continued his literary pursuits but also became a man of business, accepting the post of secretary to William Gerard Hamilton, then stationed at the Board of Trade, in 1759. Around the same period, as part of his aim of contributing to public debate in Britain, Burke assumed the role of Editor of the Annual Register, a periodical established by the publisher Robert Dodsley to provide a synoptic overview of the year’s events. From 1758 to 1763, Burke opened each instalment of the journal with a historical survey of the current war being fought between the British Empire and the French. This great struggle, later known as the Seven Years’ War, brought the antagonists into conflict in a variety of theatres, extending from America to India.

Contention in one strategically sensitive part of the Empire rapidly triggered a reaction in another. ‘The dissensions of the French and English pursued the tracks of their commerce,’ Burke commented in 1758, reflecting on the course of the ongoing strife. ‘The Ganges,’ he continued in a metaphorical strain, ‘felt the fatal effects of a quarrel on the Ohio.’

The collision in America was by far the most important and so, when not dreaming of transporting his family to the colonies, Burke was immersed in fathoming the political economy of the New World. This entailed examining patterns of trade and manufacture as well as the structures of colonial law and administration. Burke undertook this investigation together with his friend and kinsman, William Burke, when they collaborated on the composition of a comparative study of Europe’s colonies in An Account of the European Settlements in America, first published in 1757 and going through multiple editions to 1777. He never subsequently alluded to his role in the Account, and it seems that he abandoned some of its leading principles. Essentially, Burke celebrated commercial regulation in the 1750s but supported a freer trade from around the middle of the 1760s.

Burke’s change of heart can be gathered from his period of official involvement in reconfiguring the terms of British trade in the West Indies. In 1765, he accepted the position of secretary to the Marquis of Rockingham, who was just forming a new ministry under George III. Within months, Burke secured a seat in the House of Commons, entering parliament in January 1766.

Burke believed that empires might either be founded for trade, or else for the purpose of fiscal extraction

The state of the American colonies was the dominant issue in British politics. The Rockinghamites had just decided to repeal the Stamp Act and then to bind the colonies under the terms of a Declaratory Act. They next addressed themselves to commercial arrangements in the West Indies. Over the course of his first seven months in parliament, Burke deepened his understanding of conditions throughout the Empire. He embarked on a review of the navigation laws, hoping to find a way of securing the subordination of the provinces by controlling their commerce while concomitantly liberalising trade.

In general terms, under conditions of ongoing competition between the French and British empires, increased commercial freedom for Burke would still mean the subordination of the colonies to metropolitan oversight. Yet he also thought that residual restrictions on provincial trade should not be compounded by interference in the American system of domestic revenue collection. Burke believed that empires might either be founded for trade, or else for the purpose of fiscal extraction. Crude attempts to combine the two risked stirring resentment among provincial populations.

Although it was obvious that the American colonies had originally been established for the sake of commercial expansion, the British government had latterly come to view them in terms of their tax-yielding potential. This perspective began in 1764 under George Grenville, but it then continued under William Pitt and his successors. From the import duties imposed in 1767 by Charles Townshend to the passage of the Tea Act under Lord North in 1773, the mother country continued to manage its Empire by levying taxes as well as enforcing tariffs.

Burke was wary of the Americans. Their religious convictions, he believed, disposed them towards recalcitrance, while their political history encouraged a spirit of defiance. They were self-righteous and liable to be hectoring in their assertion of liberty. This applied to the arrogance of the slave-owning South as well as to the rebellious disposition of the North. They were, he complained in 1769, a ‘haughty and resentful’ people.

Yet if the British wished to perpetuate American membership of the Empire, it was necessary to accommodate the colonial character. The demeanour of the colonists was certainly fractious, but they were never systematically subversive. Burke thought that, for the most part, the Americans were driven by an underlying loyalty, and so winning their consent remained a realistic plan. Despite this option, successive British governments stoked the mood of intransigence, animated by an overblown sense of imperial pride.

Burke’s view was that Westminster confused its authority with its power. In being affronted by the audacity of the Americans, the British ministry began to fear for its own dignity. Instead of bolstering its standing by public acts of goodwill, the government resorted to shows of strength. As a result, each time Westminster tried to demonstrate its potency, it compromised its standing in the eyes of the colonists. The underlying irony was that the more the metropole opted to display its might, the more it undermined its moral authority. Imperial militancy thus led to imperial impotence.

The road to collision suddenly shortened in 1775. On 9 February, Massachusetts was proclaimed to be in a state of rebellion. Two months later, major restraints were imposed on colonial trade. Then came the military engagements of Lexington and Concord. A month earlier, on 22 March, Burke had publicised his preference for a scheme of rapprochement in his ‘Speech on Conciliation with the Colonies’. The plea failed, and the North ministry proceeded to blockade American ports under the Prohibitory Act of December 1775.

long after the American crisis had subsided, he was prepared to justify armed opposition to illegitimate authority

In practical terms, this meant that all ships in colonial waters, excepting those transporting supplies intended for British troops, could be summarily captured by the forces of the crown. In Burke’s eyes, this aggression was in effect an act of war that stripped the North Americans of adequate means to preserve themselves. Whereas before this, he believed, the colonists had chosen not to ‘proceed to extremities’, he now claimed that they were forced into battle as a means of self-defence. In effect, Burke was arguing, the contract of government had been broken. The British had relinquished their duty of protection and so the Americans were compelled to resort to their natural rights: ‘The people at that time’, Burke wrote, ‘reenter’d into their original rights.’ They had earned the right to rebel.

It is clear that Burke did more than contend for the right to revolution, he also advocated the duty to resort to it in emergencies. Later in life, in 1788 and again in 1796, he championed the cause of rebellion in India and in Ireland. It follows that there was no clear-cut breach in his career: long after the American crisis had subsided, he was prepared to justify armed opposition to illegitimate authority.

Nonetheless, the justification of rebellion was not intended to vindicate a campaign of wilful subversion: the goal of resistance was to re-establish productive civil relations. As Burke saw it, long-term harmony could optimally be brought about under the auspices of a reformed Empire. Secession, by comparison, was only a last resort. Even a year after the Declaration of Independence, Burke was proposing a new ‘compact’ between the British and the Americans that would replace what had been ‘informal’ arrangements with a new charter governing relations between legislatures on either side of the Atlantic. As late as 1781, after British defeats at Saratoga and Yorktown, Burke still hoped for an American role within the Empire.

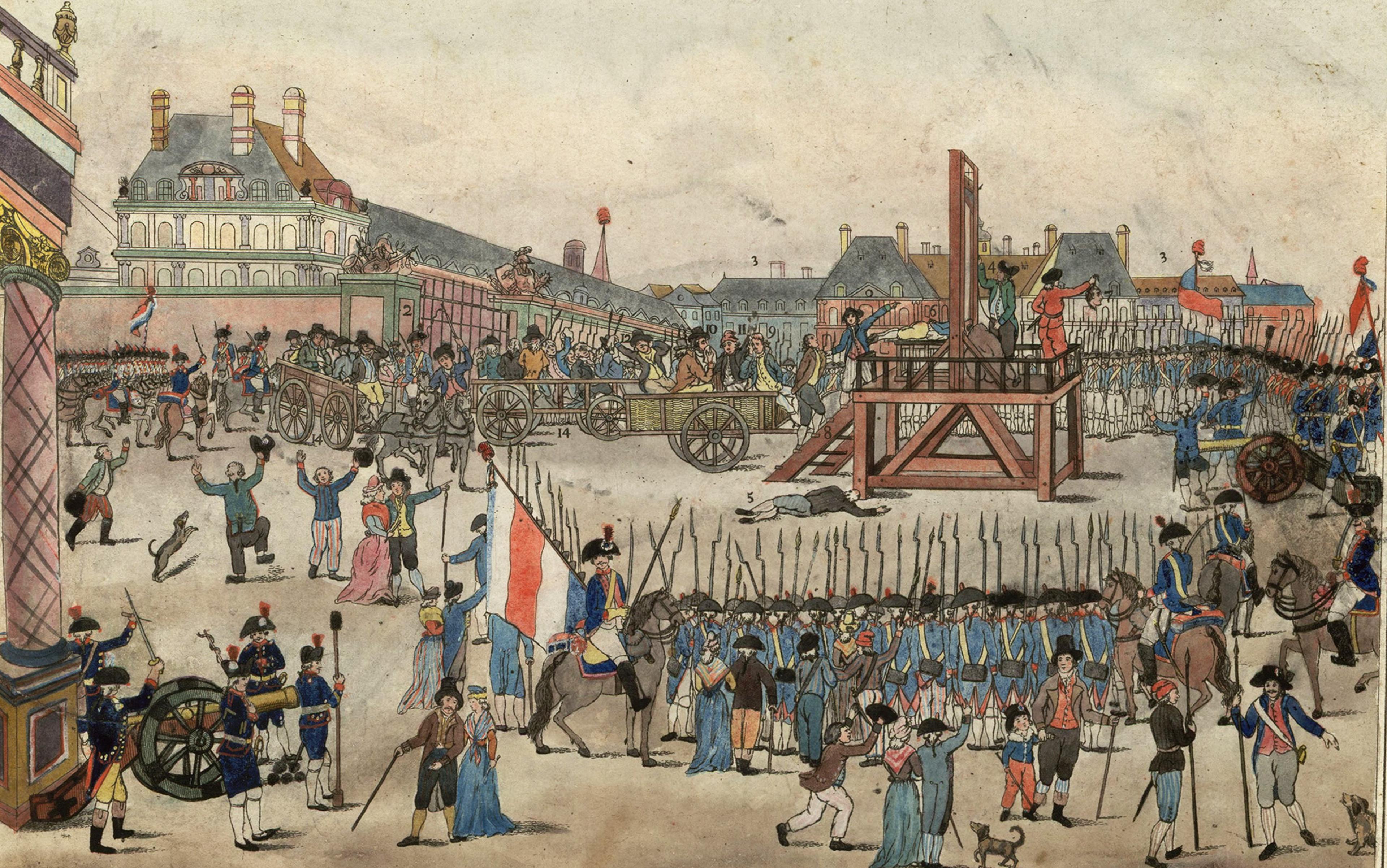

After the war, Burke came to see the provisions of the American Constitution as an impressive piece of political architecture. By the time the opportunity arose to offer his opinion on the subject, on 6 May 1791, his primary goal was to contrast the prudence of the Americans with what he saw as the revolutionary fanaticism of the French. Until his death in 1797, Burke refused to accept any parallel between the two revolutions – one, a distressing upheaval that led to a renovated system of government; the other, a scheme of permanent destruction that shattered the stability of Europe.

Most commentators have followed Burke’s one-time ally, Charles James Fox, in confusing Burke’s deliberate differentiation between these events with a seismic shift in his political convictions. Of course Fox – who became a leading opponent of Burke – was driven by resentment to insist on his former friend’s betrayal. From a more detached perspective, the depiction of Burke as an apostate dramatically simplifies his political stance. It is also prone to warp our understanding of the surrounding history.

Ever since the United States achieved the status of a world power, people have been encouraged to imagine its history as leading directly to modernity. In a similar vein, since the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity became near-universal pieties after the Second World War, the French Revolution has come to represent the advent of modern progress. Given this perception of the modernity of both revolutions, it is unsurprising that they have come to be seen as foundational events inaugurating the liberal-democratic world. At the same time, the impulse to associate the ‘sister’ republics of America and France reinforces the inclination to insulate the French Revolution from searching criticism. In making the ‘age of revolutions’ serve as the crucible of modern values, scepticism about the events of 1789 can more easily be stigmatised as ‘conservative’ or ‘reactionary’.

What Burke’s career makes plain is that actors regularly find themselves conserving radical values, or pursuing liberal causes in the name of conservatism

This tidy verdict on the meaning of progress and reaction forecloses any discussion of what opponents of the French Revolution might reasonably have wanted to conserve – such as judicial independence, economic growth and national cohesion. For Burke, the revolution in France, unlike the rebellion in America, was an assault on religion, property and government. In a post-Marxist world, the defence of religion, property and government hardly amounts to open hostility to progress. Maintaining the right to each of them is not the preserve of conservative apologists alone.

Over the past three decades, much activism in the US usually depicted as ‘left’ or ‘liberal’ was in fact devoted to conserving the remnants of a tradition threatened by the politics of austerity at home and military adventurism abroad. Just as telling, in the dying days of the German Democratic Republic, the most dogged conservatism was deployed to preserve a ‘radically’ communist agenda.

What Burke’s career along with these and other examples makes plain is that actors regularly find themselves conserving radical values, or pursuing liberal causes in the name of conservatism. Although Burke is often conscripted as an icon of timeless conservatism, his career in fact exemplifies the relativity of concepts such as ‘radical’, ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’. Each of these labels picks out a political orientation that continually adapts under shifting circumstances.

For anyone concerned to focus on what matters in politics, they would be better off evaluating the substance of particular issues than reaching to enlist canonical thinkers in contemporary causes by branding them with complacent and misleading categories.

Empire and Revolution: The Political Life of Edmund Burke (2015) by Richard Bourke is published via Princeton University Press.