Mathew Brady, the great 19th-century American photographer, said: ‘The camera is the eye of history.’ The power of the photographic eye makes the global village visible, obliterates distance, and brings strangers close up. Brady came to his insight photographing the carnage of the American Civil War. Whether he knew it or not, he was helping to inaugurate an enduring, intimate relationship between war and photography. To begin with, modern guns and cameras shared some technological parentage: they evolved from clunky machines requiring complex reloading into highly mobile, precise, and repeating, devices. They both shoot. For more than a century in newspapers and glossy magazines, at demonstrations and at Pulitzer Prize ceremonies, photographs and war have gone together, the tools of truth-seeking reporters.

But something has changed. Photoshopping has clouded presumptions about images and heroic reportage. Smartphones and Instagram have made everyone a photographer, a recorder of history. ISIS publicises beheading videos, and United States soldiers take photos of themselves abusing their wards in Abu Ghraib. For every image of a bleeding orphan from Aleppo come allegations of inauthenticity. The quantitative problems pose no less a challenge. The deluge of images – imperilled polar bears, murders in Manila, refugee columns in the Balkans (used by the pro-Brexit campaign) – inure.

Doubt about the trustworthiness of the camera as the eye of history is as old as photography, but in 1972, after Susan Sontag went to see a Diane Arbus show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it acquired a new clarity and depth. Arbus’s pictures, Sontag thought, were voyeuristic. Sontag was also disturbed by the images of the Vietnam War on the front pages. Encouraged by her editors – the late Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers – Sontag wrote the first of a series of articles on the topic for The New York Review of Books. Five years later, On Photography came out. Sontag asked if the photograph deceived and if it concealed more than it revealed.

Ever since, there has been a feud over whether you can believe what you see. Sontag herself would waver. She started out the skeptic. But by the end of her life, she came to believe that the photo, properly understood, was a humanitarian instrument, perhaps the ultimate way to help strangers appreciate another’s suffering at a distance. But understanding her conversion means retracing how humanitarianism – especially connected to wartime atrocity – and photography were entangled, to see how Sontag was part of that history, writing at a moment of anguish about the limits of human sympathy at the height of the Cold War and the explosion of atrocity imagery in its wake.

On Photography took aim at those who Sontag regarded as cynics, such as Arbus and Andy Warhol. It also lashed out against heroics, exemplified above all by the Magnum agency. Formed in 1947 by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson and other photojournalists, Magnum is now celebrating its 70th anniversary, sharing retrospectives from its canonical collections. In contrast to Sontag’s skepticism, Magnum’s shooters use cameras to cut through the fog, make the invisible visible, document wrongdoing and injustice.

Whether deceiver or witness, the photo remains the dominant way in which strangers encounter and see one other. Photos arouse fury, elation or just plain indifference about wider happenings; they shape our mixed feelings about ethical attachments to strangers, especially those in dire straits. In a world that prizes bravura and leadership, and turns social entrepreneurs into latter-day saviours, it’s hard to feel good about just watching. How do we get out of being passive spectators?

One way out of the impasse is to look differently, to behold rather than to see. Instead of looking at a photograph as consumer-voyeurs, consider how each photo has a story, is the product of a chain of observations and choices that connect two ends, the viewed to the viewer. If, as the psychologist Daniel Kahneman reminds us, feelings are one form of thinking, as fast and intuitive as the snapshot that arouses them (he calls this ‘System 1 thinking’), why not, as some photographers are enjoining us to do, slow down a bit? Consider looking at an image as a sum of interlinked observations. To behold the photo and to consider its narrative need not be such a passive act; it might yet hold a key to understanding our global attachments.

Speed can be the enemy of reason. Photos, more so in the iPhone age, are an Insta harvest. But the photo starts with the choice of the photographer to observe. For several generations, the photographer had to envision the image before peering through the camera, because taking a photo meant managing trunks of bellows, swings, tilts and stands – all to prepare the subject for long exposure times. Subjects had to keep still or be blurred. Subjects had to pose, be dead – or both.

The first generations of photojournalists worked, and thought, like studio photographers. The technological requirements of taking photos simply required staging, in the field as in the studio.

The charge that a photographer has ‘staged’ an image implies deception. Sontag took Roger Fenton, the Crimean War photographer, to task for altering the battlefield. To dramatise an after-battle scene in the Valley of the Shadow of Death, Fenton moved cannonballs. He turned the documentary object into an instrument of deceit to make the human experience of war photogenic.

Fenton wanted war to look a certain way. But it’s hard to say exactly what way; after all, he exhibited shots of the Valley both with the cannonballs and without. In its first generations, the line between taking photos and making paintings was a blurry one. Slow-drying plates also encouraged photographers to stage. In 1858, after the uprising in India, Fenton’s contemporary Felice Beato went to Lucknow to shoot the rubble in the interior of Secundra Bagh. As he set up his box camera with 10 x 12 inch plates, bystanders helped him arrange bones and skulls across the foreground. What’s the difference between this kind of early staging and other routines of managing focus, depth of field, contrast, and the choice over what to include within the viewfinder?

Interior of Secundrabagh After the Massacre (1858-62) by Felice Beato. Albumen silver print. Photo courtesy the J Paul Getty Museum

Despite the early ambiguity, photography soon moved to a documentary genre. Worldly photographers would come to imagine themselves less as studio artists staging and posing what the mind’s eye could see and more as ‘reporters’. The camera became a cool, mechanical eye, an instrument of objectivity producing images that say: ‘See for yourself.’

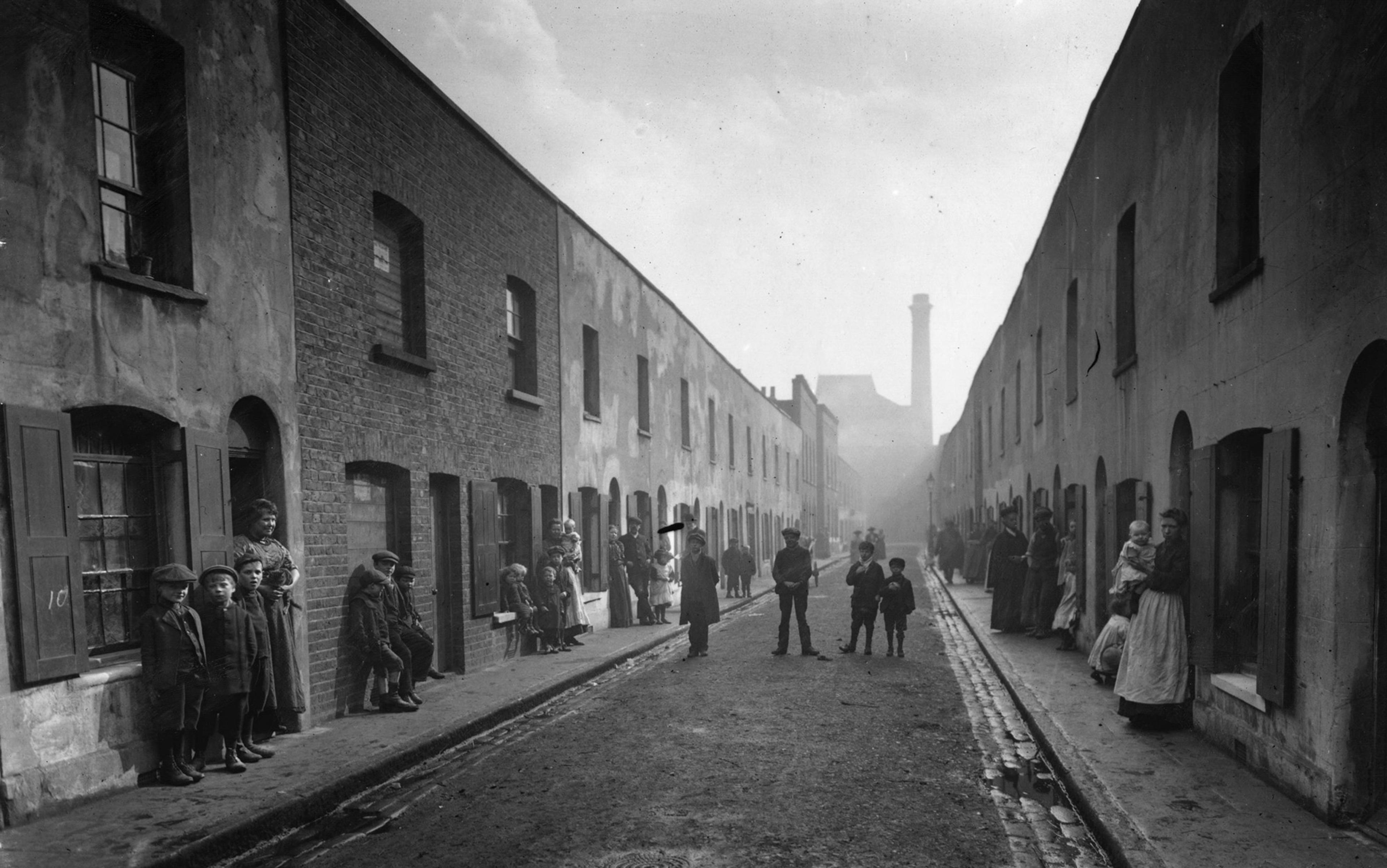

Technology played a role in this change. Cameras became portable, better able to capture action shots and street scenes. ‘Freeze-framing’ a moving reality turned a photographer into a documentarist. Instead of refined studio habitués, photographers became rugged individualists with camera bags slung over their shoulders, venturing forth into a shrinking world. George Eastman’s 1888 Kodak was a simple hand-held box capable of multiple exposures on paper negatives. The same year, the Danish-American Jacob Riis tinkered with the use of flash to illuminate the squalid dark corners of multi-ethnic working-class neighbourhoods in Manhattan. In 1889, Scribner’s Magazine published his 18-page exposé (with 19 line drawings of his photos) as an article called ‘How the Other Half Lives’. It brought to the eyes of the city’s elite what it preferred to ignore. By 1914, just in time for the war to end all wars, halfpenny papers had conditioned readers to expect pictures alongside the text.

The camera is less the eye of history than that of the beholder, each with his or her own story

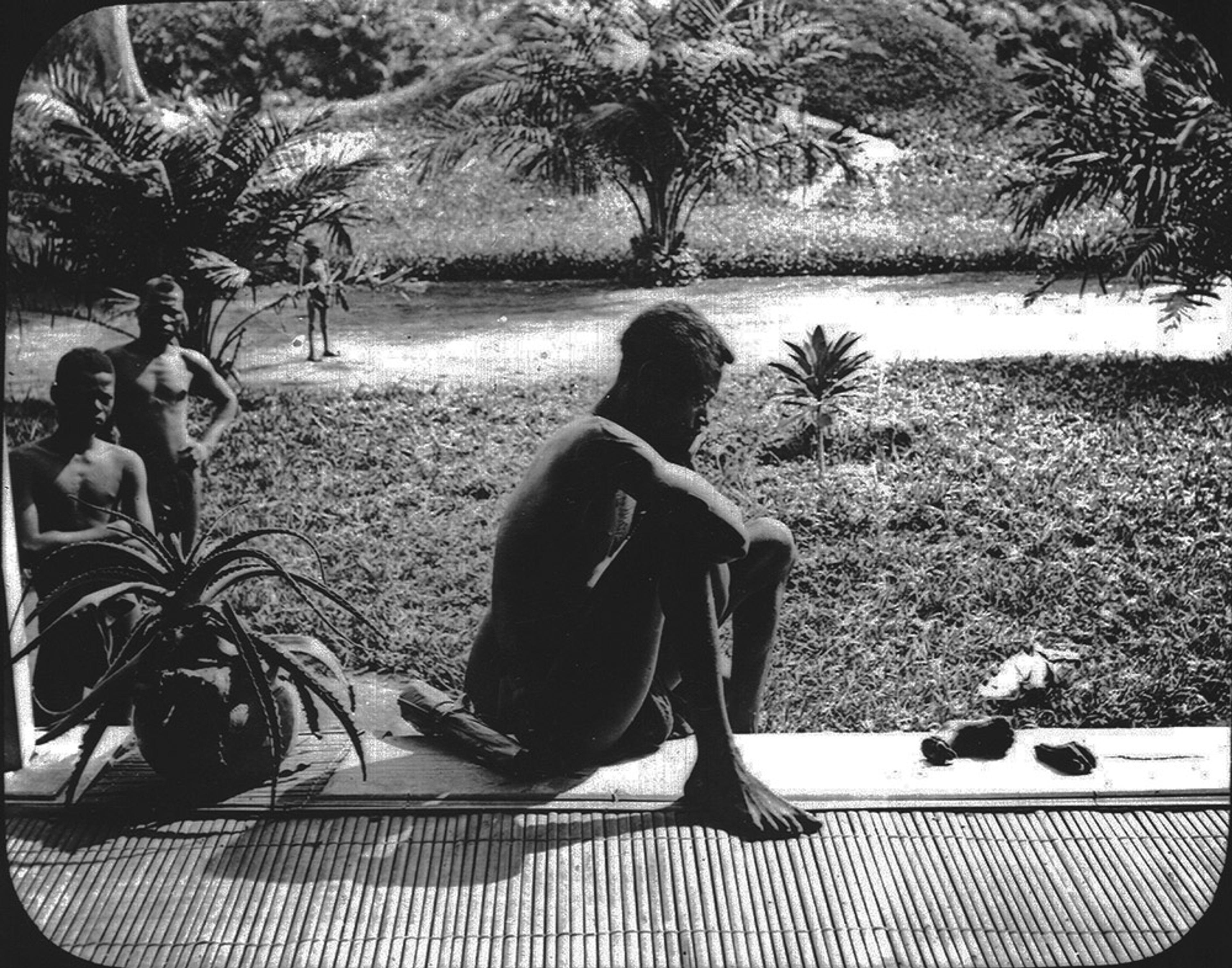

Seeing for yourself did not rely only on the pros. Missionaries were prototypes of today’s image-activists, and often took Kodaks with them to broadcast their work. Alice Seeley Harris, a ‘missionary wife’, accompanied her husband to King Leopold II’s nightmarish Congo Free State. One day, a man called Nsala, a victim of the regime’s brutal henchmen, approached Seeley Harris carrying a bundle of leaves. Opening the bundle, he revealed a child’s hand and foot. He claimed they were his daughter’s: Leopold’s sentries had, evidently, eaten the rest of her. Appalled, Seeley Harris sat Nsala down and took his photo. In it, the bereaved father rests on a cushion, his left hand cupping his chin, beside the remains of his daughter. Yet the bystanders look not at the grieving man but at the photographer. Here was documentary evidence cast in the pose of mourning.

‘Sala of Wala’ (1904) by Alice Seeley Harris. Photo © Anti-Slavery International/Autograph ABP

By then, a storm was brewing over Leopold’s Congo regime. Seeley Harris knew of the allegations that the Belgian king’s henchmen were severing the hands of workers. She also knew that her photograph illustrated a growing narrative about exploitation and empire. She got the image to the humanitarian crusader E D Morel, in London. He featured ‘Sala of Wala’ and the remains of his daughter as a slide in his lantern lectures when he toured England to mobilise public sentiment against the Belgian monarch.

Sontag’s On Photography begins with the story of humans living in Plato’s cave. They think of pictures as real life and submit to a pixilated world of fragments. ‘The camera,’ she noted in a formulation conjugated to enrage the eye-of-history believers, ‘makes reality atomic, manageable, and opaque. It is a view of the world that denies interconnectedness, continuity, but which confers on each moment the character of a mystery.’ Since the image explains nothing, it’s the perfect tool for inexhaustible fascination, confusion and fantasy; it’s how modern culture made the past consumable. In 2014, Sontag’s biographer Daniel Schreiber noted the irony that the photographer herself acquired celebrity as a photogenic – and photographed – glamour-author.

Still, in Nsala, Anglo viewers saw a victimhood that illustrated the moral qualms over slavery and empire. No doubt implicating a rival empire made the visual corroboration of imperial crimes easier to accept. The career of Seeley Harris’s photograph was also an early instance of photoreportage as the exhibition – some would say exploitation – of the pain of others, especially non-Western people. In this foundation of photoreportage, exploited or brutalised people become props in the growth of Western humanitarianism. As Mark Twain wrote in his send-up of King Leopold’s imagination, King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905): ‘the Kodak has been a sole calamity to us… [It is] the only witness I couldn’t bribe.’

During the war in the Philippines (which started in 1899 and ended with the final defeat of Moro resistance in 1913), photographic images played an important role in a furious debate over the meaning of humanitarianism. In 1906, on the sides of the volcano Bud Dajo, US troops slaughtered up to 1,000 Tausūg Muslims. President Theodore Roosevelt celebrated the soldiers as brave patriots. Orders went out to seize any evidence to the contrary. But an unknown photographer followed the troops of Captain A M Wetherill to a gully full of cadavers of slaughtered civilians. The cameraman set up his tripod and box, got the soldiers to pose as the grim, weary victors, and took the shot. The picture got into the hands of a teacher, who took it to Japan while on furlough, and from there it reached stateside.

This photo shocked the American public. In the wretched tangle of bodies and clothing, only a few Filipino faces are visible, all looking skyward. Who is watching whom? The bare breast in the middle was also the subject of dismay. When I showed the photo to a friend recently, she said she could almost smell the stench of rotting flesh. In 1906, the civil rights activist W E B Du Bois wrote to the president of the Anti-Imperial League: ‘I want especially to have it framed,’ he said, ‘and put upon the walls of my recitation room to impress upon the students what wars and especially Wars of Conquest really mean.’

After the First Battle of Bud Dajo, 7 March 1906, by an unknown photographer. Public domain photo

What did the photographer intend? Were the US soldiers, posing with apparent pride, tricked? Then there’s the teacher, the smuggler, the censor, the editor. The only non-watchers are dead. With each beholding, the story of the photo changed course and thickened with significance.

The stories of photographs are important, because photographers don’t necessarily create the meaning of their photographs. Was the US army reserve specialist and Abu Ghraib guard Charles Graner intending to help to discredit an entire war when, in 2003, he snapped Lynndie England, his girlfriend and co-guard at Abu Ghraib prison, posed as if shooting the penis of a cloaked prisoner? Indeed, the images were initially understood, by the US and the UK intelligence services, as evidence that the inmates were being ‘appropriately’ treated. When a reporter from the German magazine Stern interviewed England in 2008 after her 521-day sentence, she explained that it all started as an extension of a Chuck Norris gung-ho movie – and she reminded the reporter that, after all, the first people to look at the images of routinised humiliation were her superiors: ‘When you show the people from the CIA, the FBI and the MI [Military Intelligence] the pictures and they say, “Hey, this is a great job. Keep it up,” you think it must be right.’

The MI guys were the first to see for themselves. ‘They were all there,’ said England of her superiors, ‘and they didn’t say a word. They didn’t wear uniforms and, if they did, they had their nametags covered.’ The only one who couldn’t see the action was the prisoner.

Lynndie England with Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib, 2003, by Charles Graner. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

Unlike Graner and England, none of the officers or intelligence officials who solicited and viewed the images ever did time. Yet they played a decisive role in the making of Abu Ghraib’s gallery of depravity. Bud Dajo and Abu Ghraib remind us that the photograph cannot speak for itself. The camera is less the eye of history than that of the beholder, with each beholder viewing the result from his or her place, with that particular story in mind.

What is often called ‘photographic objectivity’ was the stepchild of the First World War, a conflict that professionalised visual reportage and the scramble to control it. Technologies set up the photographer, riding the authority of new professionalisation, to be the kingmaker of a new reportorial regime. The small-plate Ermanox camera shrank the bulky box but wielded a large aperture; Leica unveiled the 35mm roll of film, so a person behind the lens could cock and repeat up to 36 shots a canister. Faster lenses, rapid film advancement, detective-style shooters made handling easier, less obtrusive and more intuitive, perfect for capturing action, making the motion the picture itself. Improvements in developing and printing helped, and freed the photographer to work in the field, concentrating on personal expression or journalistic reportage. When Arbus began to take her first photography lessons from Berenice Abbott, she could declare: ‘Photography is a new vision of life, a profoundly realistic and objective view of the external world.’

Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. US troops assault Omaha Beach during the D-Day landings (first assault). Photo by Robert Capa © International Center of Photography/Magnum

Capa, the Hungarian-born celebrity photojournalist and war photographer, took the new ideal of the photographer, and the possibilities of the new technologies, to iconic heights. When he jumped off the landing vessel at Normandy in 1944 to shoot the first moments of D-Day, Capa immediately sent back his rolls to London for developing so he could follow the action. He didn’t have to worry about the darkroom. He didn’t have to set up complex gear. He was a lot like the GIs he accompanied. Of his landing in Normandy, Capa wrote in Slightly Out of Focus (1947):

The next mortar shell fell between the barbed wire and the sea, and every piece of shrapnel found a man’s body. The Irish priest and the Jewish doctor were the first to stand on the ‘Easy Red’ beach. I shot the picture. The next shell fell even closer. I didn’t dare take my eyes off the finder of my Contax, and frantically shot frame after frame. Half a minute later, my camera jammed – my roll was finished. I reached in my bag for a new roll, and my wet, shaking hands ruined the roll before I could insert it in my camera.

This was the opposite of staging. A darkroom error, by a hasty assistant, destroyed all but 11 of Capa’s original 106 assault-frames of his landing in Normandy. A decade later, Capa stepped on a landmine just south of Hanoi. It killed him.

The era of the photo as pre-visualised perfection was gone forever. Realism – gritty, spontaneous, candid, even blurred and grainy – became the hallmarks of the new aesthetic, which found expression in the Soviet utilitarian imagery of a Dmitri Baltermants, or the montages of German printers. The new tension was no longer between art-form and the documentary, but between a spirit of realism and the daring of the heroic photographer raking the scene for – as Cartier-Bresson put it – ‘the decisive moment’. Magazines such as Vogue, Paris Match, Der Spiegel and Life specialised in the glossy photograph for the mass reader-viewer. In fact, pictures no longer illustrated the story; they became the story, the prize-winners.

Paris Match’s slogan was: ‘The weight of words, the shock of photos’ – the words and the images were all tangled up

In 1931, Walter Benjamin wrote ‘A Short History of Photography’. His essay probed some of the same questions that Sontag would address 40 years later. It’s here that we find Benjamin’s much-quoted line: ‘There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’ In contrast to Sontag, Benjamin saw photos of others’ pain and suffering bringing a sharpened, more ‘singular’ truth about personal experience to a viewer. Yet, Benjamin also saw that as cameras grew more compact and the images became more fleeting, photography grew more shocking and brought ‘the viewer’s association mechanism to a standstill’ – the photo could arouse feelings but dull the observer’s understanding. In Kahneman’s terms, photos stoked System 1 thinking.

Benjamin saw the problem. But he also saw that photos seldom came alone. In magazines and newspapers, they were surrounded by words. The caption, Benjamin noted, made sense of the image. The words, he wrote, would ‘implicate photography in the literalisation of all conditions of life and without which all photographic construction is stalled in vagueness’. Paris Match’s slogan was: ‘The weight of words, the shock of photos.’ The words and the images were all tangled up.

Disconnecting the image from the word prioritised System 1 emotion (anger, sadness, the gamut of feelings) without the understanding and precision of words, the meaning that came from System 2 processes.

Actually, Capa, the fatigued vet, got it. As the Second World War came to a close in 1945, and as Allied troops liberated concentration camps, he returned to London to recover. Capa passed cameramen scrambling eastward with their gear, hoping to be the first to shoot the evidence of genocide. Today the spectacle might horrify, he observed, but it would be forgotten tomorrow in the barrage of imagery that he himself had contributed to making.

As war zones doubled as sites of humanitarian calamities, the challenge of making sense of the image from far away grew. That did not thwart the heroes. In her final book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Sontag noted sarcastically that Magnum’s 1947 charter claimed a moral mission to chronicle. Magnum was a global business, she observed, ‘with wars of unusual interest (for there were many wars) a favourite destination’.

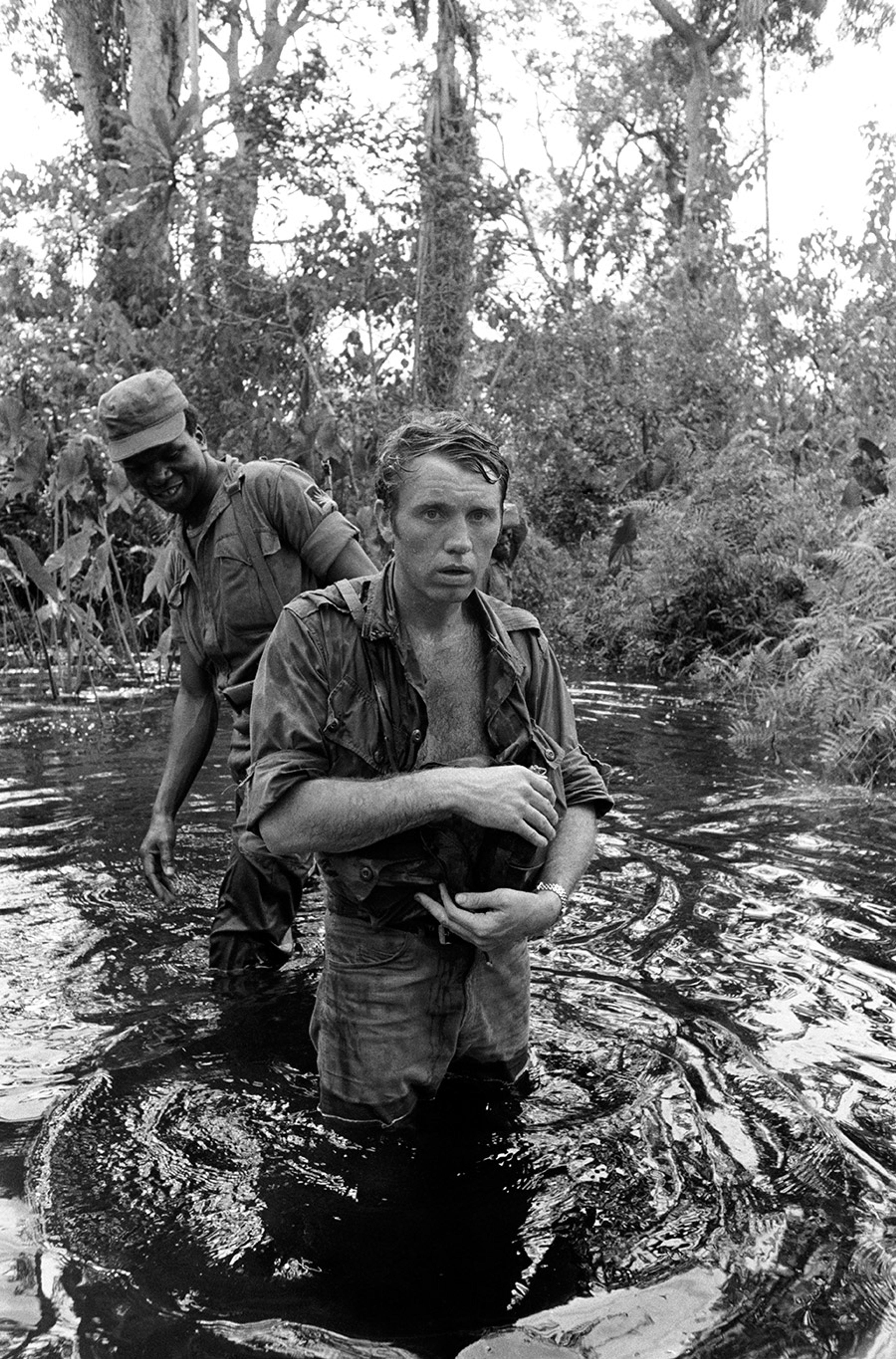

Vietnam brought a photographic barrage. Life began its coverage in 1962. But the magazine depended on family-doctor waiting-room subscriptions, and after 1967 it backed off graphic coverage of an escalating war. Vietnam also brought new advances in diffusing photographic imagery. In 1967, after shrapnel nearly severed his leg at Bu Dop, the German photographer Horst Faas turned the AP bureau in Saigon into a new-style media hub. Hitherto, bureaux had to send out their prize pictures with ‘pigeons’, human couriers who flew around the world with photographic cargoes. Using a cylindrical Wirephoto drum that took about 15 minutes to send a print, Faas devised a way to get pictures to editors almost immediately. It clogged up international telegraph lines, but got photos to editorial desks fast. Newspaper readers felt like they were watching clipped history in real time. Long before Facebook and Instagram, Faas shattered the distance between the source and the observer.

The photographs from Vietnam shocked media veterans. Marguerite Higgins and Joseph Alsop, for example, heirs to the moral faiths of the Second World War, preferred tidier reportage, with good guys clearly good and bad guys clearly bad. Nothing about Vietnam was tidy. By 1968, pictures of the muddied face of the Leica-strung cameraman alongside the muddied GI had become a pictogram of a counter-insurgency gone terribly awry.

It’s tempting to infer that Sontag lashing out at Magnum was a reaction to her feelings about being manipulated

It was in 1968 that Eddie Adams’s shot from Saigon shocked the world. The image of the South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, chief of the national police, firing a bullet into the temple of the Viet Cong (VC) officer Nguyen Van Lem helped to drain whatever convictions remained that the Saigon regime was worth dying for. The contact sheets reveal that Adams was shooting and cocking his way backwards as the small crowd of angry captors and the seized VC sharpshooter got closer. Then Loan stepped forward and shot Lem. Adams wasn’t even sure of what he’d got until later, when his AP-editor Faas picked it off the contact sheet and wired it to New York. Editors at The New York Times debated what to do. It was an unforgettable photo, but was it too much? Theodore Bernstein, the assistant managing editor, decided to balance Adams’s picture of allied brutality (which the Times printed big) with a smaller photo of a child killed by VC troops. Unsurprisingly, the latter image used to ‘balance’ Adams’s has been forgotten.

‘Saigon Execution’ (1968) by Eddie Adams. Photo by Eddie Adams/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Adams’s photograph enraged Sontag, and not just for its injustice. She thought it was a pernicious form of staging masquerading as reflex spontaneity. She charged that, had Adams not been there, camera loaded, the killing would never have happened. Loan killed Lem because there were witnesses, not just on the street, but – via Adams, Faas and AP – the whole world, according to Sontag.

On 8 June 1972, four years after ‘Saigon Execution’, Nick Ut photographed the scorched, naked nine-year-old girl Phan Thi Kim Phúc fleeing her burning village after a South Vietnamese napalm attack. Sontag saw this one in a different light; by then, the war was a débâcle. Ut’s image, Sontag argued, helped to turn viewer outrage into citizen action. On 9 June 1972, when it printed the photo, The New York Times’ caption read: ‘ACCIDENTAL NAPALM ATTACK: South Vietnamese Children and soldiers fleeing Trangbang on Route 2 after South Vietnamese Skyraider dropped bomb. The girl at the centre has torn off burning clothes.’

The Napalm Girl, Trang Bang, Vietnam 1972. Photo by Nick Ut/AP/Rex/Shutterstock

When Sontag composed her first essay on photography, for Epstein and Silvers, she was thinking about ‘Napalm Girl’. The sight of her agonised face ‘was more memorable than a hundred hours of televised barbarities’, wrote Sontag. ‘It may even,’ she speculated, ‘have done more than anything else to mobilise the anti-War movement.’ Without evidence, but with characteristic assurance, Sontag claimed that ‘the shock of Kim’s face changed history’. She herself had fallen prey to the System 1 mode, her rage was taking over; it’s tempting to infer that Sontag’s lashing-out at Magnum was itself a System 1 reaction to her System 1 feelings about being manipulated. Either way, she was swinging back and forth, at once accusing photographers of manufacturing history while bowing to them for giving observers new means to change it.

What she did not do was probe the story behind the image. In fact, the editors at the Times responded to Ut’s photograph with some ambivalence. Do we show her genitals on the front page, not to accent the pain on her face but to avoid offending the prurient? They decided to blur her groin, using a technique called, ironically, burning and dodging. They also cropped the photo to excise the image of the other journalists on the left, one of them reloading his camera. Better not to remind readers that the photographers were part of the story. (‘Napalm Girl’ was back in the news last year when Facebook banned it for indecency. I guess they are less ingenious than the Times editors. When users complained, the firm relented, with an anodyne statement about ‘the history and global importance of this image in documenting a particular moment in time’.)

Vietnam often dominates discussions of reportage and sympathy. But it wasn’t the only place that photojournalism contended with the Cold War getting hot or the souring of developmental dreams.

In 1967, a different kind of horror broke out in Biafra. A year earlier, the economist Albert O Hirschman went to the secessionist state in eastern Nigeria to evaluate the World Bank’s development projects, including the Bornu rail line that crossed Nigeria’s Hausa-Igbo frontiers. Hirschman’s report, called Development Projects Observed – note the verb choice – called upon fellow economists to observe; to not allow the mystique of abstract theory blind them to the world. The book came out and Nigeria soon erupted into a brutal civil war that would kill three million people. Hirschman was alarmed: how could I not have seen this imminent disaster? What’s the point of urging others to observe if I could not see what was before me? These doubts about his acumen sent Hirschman back to the drawing board and resulted in Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970), a social sciences classic.

I went back to Hirschman’s field-notes, the writer’s equivalent of contact sheets. Had he been blind? His notes were full of griping Nigerian voices. But the complaining was mainly about freight rates on trains compared with buses, and about price-gouging of ground-nut farmers at the railheads. If you go looking for evidence about the economy, that’s what you’ll get. Even economists start with a picture in their head, and pose the questions that beget the answers.

‘When in bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, uplifted – yes – but whom has it saved?’

Photography is not so different. When you lift the viewfinder to your eye, you are already making choices about what to include in the frame and what to exclude; in a way, it is staging. Brady’s aphorism about the eye of history reflected an enthusiasm about the machine. It is easy to forget, as Brady did, that it’s still people, making decisions, trying to observe.

The Biafran war of 1967-70 was among the first televised and mediatised civil conflicts that led to a humanitarian disaster. It was a harbinger of wars to come, and photography changed too. After Biafra, war photography and humanitarian photography shaded back and forth into one another. Don McCullin, a British photographer who had worked in Berlin during the Cold War, as well as Cyprus and the Congo, became famous for his Biafra photographs. They were unflinching black-and-white shots of emaciated children with distended bellies. The absence of colour in McCullin’s images draws the eye to the distortions of his subjects’ bodies. The day he left for Biafra was the worst of his life. He arrived at a scene of nearly a thousand children ‘dropping down dead in front of me and crawling around on their stomachs with their insides hanging out’ (the ailment is called rectal prolapse, induced by chronic diarrhoea caused by starvation). McCullin’s professional instinct took over and his Nikon F went to work.

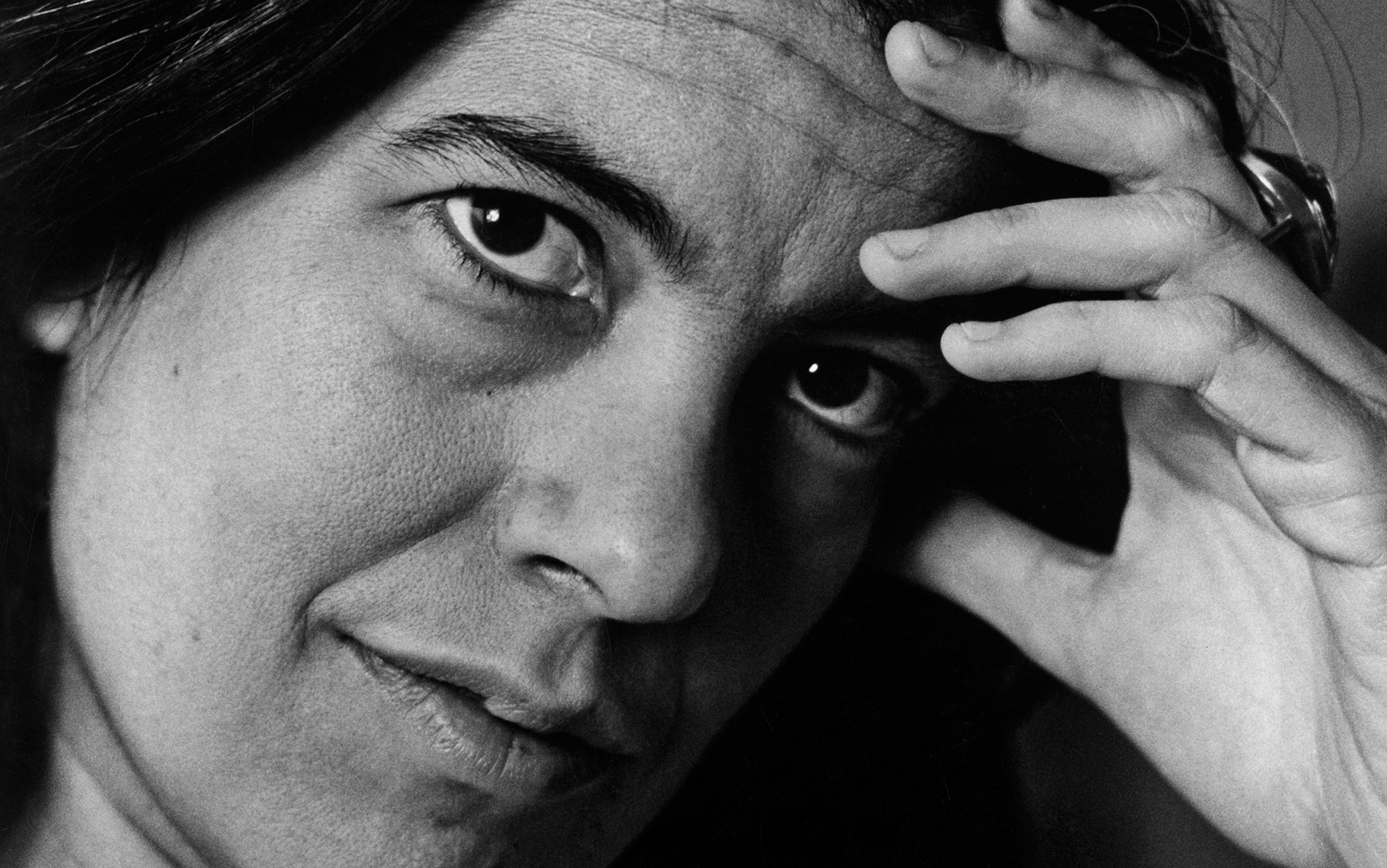

Don McCullin in April 1968, in Onitsha, Nigeria. Photo by Gilles Caron/Fondation Caron/Getty

Sontag lamented that McCullin’s repertoire was another atrocity show, even though the growing affinity between photographers and humanitarians involved dropping the visage of objectivity that Sontag criticised. In 1971, McCullin worked with Gilles Caron and other French doctors to create Médecins Sans Frontières (Caron later disappeared on Route 1 between Cambodia and Vietnam in territory controlled by the Khmer Rouge). Nineteen-seventy-one was also the year that humanitarianism, philanthropy and rock’n’roll locked arms in George Harrison and Ravi Shankar’s Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden. The following year, the documentary format hit movie theatres, inaugurating a tradition of the benefit concert and celebrity humanitarianism.

Sontag despaired that human deprivation was becoming a new genre of entertainment. McCullin too worried that what all the festivity meant was that caring was becoming a commodity. McCullin’s book, published in 1971 as The Destruction Business and updated a couple of years later with the new title Is Anyone Taking Any Notice?, was sprinkled with dark phrases from Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize speech: ‘When in bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, uplifted – yes – but whom has it saved?’ The cover of the revised edition said it all; if McCullin was best-known for gritty portraits of conflict and destitution, photos that dared you to blink, the jacket bore the negative of a dead bird lying on snow, like a ghost for spring.

Sontag would later write a preface to one of McCullin’s anthologies. But their views were not entirely compatible. For Sontag, the photographic medium was tethered to a business of image-making that turned the message into the simulacrum of reality; photographers could not but widen the gap between the observed and the observer. For McCullin, the image was blameless in the world’s suffering. ‘I don’t make any protest other than take photographs and show how bad it is.’ In other words, why blame the messenger?

Ifirst read On Photography more than 30 years ago, in the wake of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, when I was tempted by the calls of global photojournalism. I had a poster of Alberto Korda’s ‘Guerrillero Heróico’ portrait of Che Guevara on my wall. With that super-ego in my head, and equipped with a Pentax K1000 – an all-mechanical entry-level brick of a thing – I set off for the Andes and Central America to prove Sontag wrong. It was 1981.

Today, I concede the point. At worst, images turn distant suffering into a show, grist for a society of spectacles, turning distress into entertainment. Even the eye of history has become a commodity. Korda’s Leica, the one that shot Che looking into the distance and that yielded the visage of our revolutionary illusions, sold last year for $20,340. His son, Dante Díaz Korda, auctioned it. The starting bid was $134.

At best, according to the American photojournalist Lynsey Addario, photographs might bring material aid. Addario is a veteran photographer of Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Darfur and the Congo. She has won a Pulitzer, a MacArthur grant, and is one of the more celebrated heirs of Capa’s legacy. Like Capa, Addario is a realist shooter, but she doesn’t follow the master’s affection for what Caroline Brothers in War and Photography (1996) called Capa’s ‘evocative blurring’. Addario’s shots sharpen the lines to a razor’s edge. A viewer dare not blink lest the subjects of her image explode out of control. In 2011, she got caught in a firefight in Libya; Capa’s words came to mind: ‘If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.’ In Libya, as she recounts in her memoir It’s What I Do (2015), Addario told herself: ‘If you weren’t close enough, there was nothing to photograph. And once you got close enough, you were in the line of fire.’

In 1996, when Addario launched her reportage career in Buenos Aires, she had images of the Biafran famine in her head. She took pictures of the Argentine Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, by then the shopworn symbols of human-rights defiance, but found them flat, derivative. Addario shook her head; she hadn’t gotten ‘close enough’. She turned, in her quest for ‘a strong humanitarian angle’, to Africa, specifically Darfur. Addario thinks that the antidote to the passivity of pity and the surfeit of images is more and better imagery – not less. ‘I always felt horrible photographing people in such states of misery,’ she recalled about shooting in Mogadishu, ‘but I hoped my images, in bringing greater awareness of the desperation, might also bring food and medical aid.’ Her view was not so far from McCullin’s.

In On Photography, Sontag targeted her indignation at the shooter’s conceits: the eye of history, the authoritative image-taker freeze-framing the past, once and for all. No one believes that any more. But how far should we lower our expectations? Do we want photographers to fill galleries with images of injustice and melting ice-caps, to remind us of how fallible and fragile humans are, and then nod with the media critic who calls it an expression of neo-liberal hegemony – or some such theory?

Worried about over-theorised paralysis, Sontag returned to the thematic scene. In 1993, she went to visit her son, David Rieff, who was reporting from the siege of Sarajevo. Amid the shelling of Bosnian homes, Sontag despaired about the West’s inaction. In late 2002, as the US launched its catastrophic war in Iraq, she wrote ‘Looking at War’ for The New Yorker, which became her last book, Regarding the Pain of Others.

Photos give feeling but cannot explain. They need words to join observed and observers in shared understanding

That book conceded a space for Sontag’s argument of 30 years earlier about the anaesthetic impact of images of suffering, and McCullin and Addario’s best-case perspective, in which photographs can raise consciousness among viewers and bring succour for victims. In her final work, Sontag rounded on media-studies gurus who delighted in merely identifying the alienating divide between the spectator and the subject, a divide she had done so much to identify and magnify in the first place. She also criticised soft-minded viewers – an earlier version of herself? – who were ‘shocked’ at worldly depravity despite the visibility of distant suffering.

Was it possible to imagine photos fostering ethical attachments between strangers? In contrast to On Photography’s moral judging of the producers, Regarding the Pain of Others takes a more modest, inconclusive stance on this inescapable problem. The modern humanitarian who wants to attach strangers – observers – in bonds of mutual regard cannot do so just with photos. Photos give feeling but they cannot explain. They need words, narratives to make sense, to join observed and observers in something closer to shared understanding. Photos make emotions and memories; but stories make meaning. They need, at least, Benjamin’s humble captions. ‘Narratives,’ Sontag wrote, grandstanding somewhat, ‘can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.’

It is worth remembering that Sontag wrote Regarding the Pain of Others before the onslaught of the digital age. The digital turn explodes the range and quantity of images, from the dick-pic to videos taken from Aleppo rooftops as Syrian bombers release their payloads. The digital turn also makes finding the story even harder, and all the more important.

Some photojournalists want to slow things down. Addario and ‘Abbas’ – one of Magnum’s cameramen once dedicated to shooting the northern side of the Vietnam War – have pulled back from the news cycle in order to, as Addario puts it, ‘shoot with patience’. Instead of chasing jeeps, they now go for producing books or feature montages. Abbas is adamant about the sacredness of the shot: ‘Once you take it, that’s it: you don’t crop it, you don’t touch it, you don’t fool around with it.’ The observer’s skill, he reminds us, is observing before shooting. The menace with digital is that, in a dozen ways, it makes it easier than ever to alter and de-contextualise the image from the story it’s part of.

The horror of Syria has brought an array of challenges to piecing together the narrative. We get the pictures that ‘make’ history, like the image of Aylan Kurdi, the three-year-old boy washed up on a Turkish beach in early September 2015, after his family had been denied asylum in Canada. Nilüfer Demir, the Turkish photographer, had been patrolling the beach shooting boatloads of Syrian fugitives trying to cross the Mediterranean. One morning, she happened upon the toddler before anyone else. At first, the government of Canada’s then prime minister Stephen Harper denied that there had been any asylum application. As the image went viral, however, Ottawa was forced to concede the truth about the story. The Harper regime would get trounced two months later in the elections.

Some European governments welcomed refugees. Yet, the World Press Photo jury decided not to award Demir a prize because the image depicted despair. Jurors wanted a story of hope. For others, the image became one of defiance, like the enlargement on a bridge in front of the headquarters of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. ‘Dead Europe,’ reads the slogan, ‘Death and Money.’ The German male graffiti artists gave themselves credit, but left the female Turkish photographer out of the picture.

Nilüfer Demir’s photo of Aylan Kurdi as graffiti art by a bridge over the Main river in Frankfurt, 2015. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

In the middle, observers, editors, advocates, make decisions as to how to represent tragedy. Those decisions may be based on style, ideology, intellectual property, or technical questions. Newspapers such as The Independent in the UK and Le Monde in France put Demir’s shot on the front page. The Guardian and The New York Times elected to publish not the face-in-the-sand photo, but the kinder, if sadder, version of Aylan draped in the arms of a Turkish policeman. The Times placed it deep in the paper. Social media and advocacy groups plunged the image into instant global circulation. Peter Bouckaert, the emergencies director at Human Rights Watch, fired out the shot from his Twitter account: ‘Just imagine this was your child. Please don’t look away.’

It took Sontag decades to let her skepticism about heart-warming beliefs in technological progress, burnished in the age of Cold War certainties, give way to uncertainty and despair. In a sense, her voyage was part of the debate about photography and sympathy, spurring on a quarrel over whether the camera helped or hindered. Looking back, we can see the arc from heroic reportage to waning confidence in photographic objectivity. We were left poised between cynical disbelief and humanitarian urgency. In between the two is moral ambiguity, a realm that expands as the manufacture of images goes digital and their circulation goes global.

Until now, the question has been: does a photograph make us act, or does it dull our senses? That question preoccupied Sontag. But it is too blunt; it misses that the photo works both ways. The photo is neither the answer nor the obstacle to our capacity to sympathise across distances. The camera gives feeling and emotional power, but insight comes from beholding the photo as an image made by events, and links that chain the viewed and the viewer in a shared, if often disjointed, narrative. The distance between them is connected by choices and small, forgotten acts of posing, staging, shooting, editing, selecting, captioning, circulating and making strangers visible to one another. These everyday practices of turning photos into stories that connect the viewer to the viewed may not dissolve moral ambiguity, but understanding them helps turn the passive spectator into a more active witness.