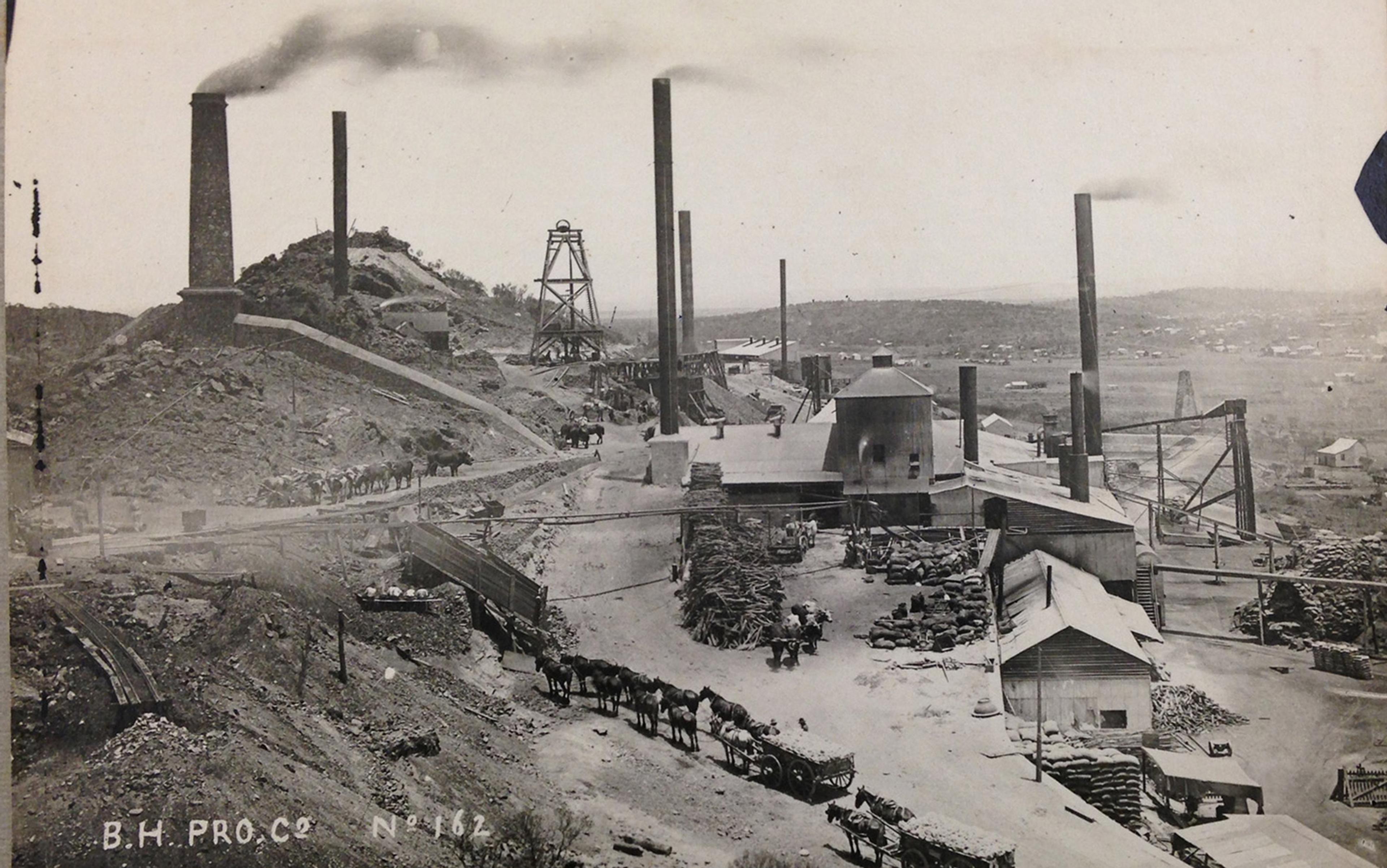

Tom Bailie grew up on a dryland farm in Mesa, Washington, just downwind from the massive Hanford plant founded in 1943 to produce plutonium for the Manhattan Project. Bailie often served as an informal spokesman for the ‘downwinders’, the people who believed they were poisoned by fission products that flowed from the plant on air currents, along underground aquifers, and down the Columbia River on the dry plains of eastern Washington. Bailie shows up in dozens of articles and almost every book about Hanford. Talking to him, it’s easy to see why. He has the gift of gab spiced with a knack for colorful sound bites. He also looks, dresses and drawls just like a farmer on the Western range should, which makes for good copy. Because it takes historians a long time to research a story, I got to know Bailie well. Over the years, we became friends.

The first time I met him, we climbed into the swather he used for cutting crops and rode up and down a field of alfalfa he was getting ready for export to Japan. He told me that the former CNN journalist Connie Chung had ridden in the same seat. I got the message that he was offering me a photo-op worthy of national TV. As he drove, he kept up a monologue.

‘When I was a kid in the 1950s, I used to love Buck Rogers, and one day I looked out the window to see men in space suits shoveling dirt from our front yard into little metal boxes. I was thrilled, but my mom panicked. She ran out and asked the scientists what was wrong. “Nothing, M’am,”’ Bailie cuffed his hand over his mouth to mimic a voice behind an assault mask, ‘“everything is just fine.”’ The scientists asked for the beaks and feet of the geese his father had shot, then they left.

‘I finally realised,’ Bailie announced on another day, ‘why me and my buddies are still going strong, and the goodie-two-shoes we went to school with are sick or dead.’

‘Why, Tom?’

‘Because when their mothers told them to eat their vegetables and drink their milk, they did! Meanwhile, me and my friends snuck off to the store and bought Twinkies and Coke.’

One day, Bailie took me to a low-slung, cement-block building abandoned behind chain-link fencing. It was the old Pasco slaughterhouse. ‘These guys in tan suits used to pull up in beige cars marked with consecutive plates. They were looking for our crooked lambs and calves,’ he said. He leaned closer to make sure I was listening. ‘Twenty per cent of our livestock were malformed. The feds would go in, say something to the manager, and then come out with stainless steel containers. They were collecting organs — like regular body snatchers.’

There are some truths that most people don’t believe, not because they are not true but because, like the mythical prophet Cassandra, society is resistant to them

When he ran for the state legislature in the 1980s, Bailie says he started to notice something. He campaigned among senior citizens (‘because they vote’). In some communities, people in their 90s were still farming. His campaign manager came from the same neighbourhood as him. Bailie asked him: ‘Why we don’t have any old folks?’

‘They all died of cancer.’

‘Why is that?’

‘I don’t know.’

Bailie asked the elderly farmers if they used pesticides. ‘Yes, we did,’ they told him, ‘until that communist lesbian bitch Rachel Carson came along.’

‘See,’ Bailie said to me, ‘everyone used DDT, so that didn’t make the difference.’

Bailie said he saw a pattern. The communities where elderly people still lived were in the valleys, but they were missing in hamlets on the hillsides. When I gave him a blank stare, he pencilled out for me how the wind followed the contours of the land, funnelling up through the edges of valleys.

In the decades after the Chernobyl disaster, state-funded scientists in the United States determined that landscapes polluted with radioactive isotopes from weapons production required $100 billion amelioration programmes. In these places, residents had been exposed to low doses of ionising radiation since the mid-1940s, longer than anywhere else in the world. Richland, Washington, was a model city re-built in 1943 for plutonium plant operators. Scientists claimed that the local testimonies of chronic illness and sick children were scientifically anecdotal; that, on average, rural inhabitants were no less healthy than other populations. Internationally, experts argued that people living near radioactive zones in the US, Ukraine and Russia were just fine. If they were sick, it was because they had ‘radiophobia’, or they drank too much, smoked and had poor diets.

In this light, recent reports of deformed barn swallows in the Chernobyl zone and mutant butterflies appearing a year after the meltdown of three reactors in Fukushima make for especially worrying copy. Butterflies and birds don’t smoke, drink, or suffer from radiophobia. For the past seven years, I have spent a great deal of time in the radiated traces of the world’s first plutonium plants — the Hanford factory in eastern Washington State and the Mayak plant in the southern Russian Urals. As countries from the Middle East to the Baltics gear up for a new generation of nuclear power reactors, it is worth taking another look at how scientists laid claim to the ‘truth’ to dismiss the testimony of local farmers such as Tom Bailie, and how farmers fought back to cast doubt on the experts.

As Bailie tells it, he didn’t always harbour suspicions of government agents in unmarked cars. He said he was once a freedom-loving, take-it-or-leave-it American patriot. He tried to enlist during the Vietnam War, and was rejected because of birth defects. Even so, he spurned the hippies and peace movement, and was proud of living alongside the plutonium plant in a community of like-minded people who knew the value of a strong defence. After the Chernobyl disaster, however, de-classified documents showed that the Hanford plant’s routine dumping of radioactive waste exceeded the Chernobyl blast several times over. This news gradually eroded Bailie’s political certainties.

In the early 1990s, along with 5,000 other plaintiffs, he filed suits against five corporations that had operated Hanford for the US government. The ‘downwinders’ waited anxiously for the results of a federally funded Hanford Thyroid Disease Study (HTDS), hoping it would provide determining evidence. But the case, which seemed so clear to plaintiffs living in areas where most people seemed to be chronically ill, proved elusive.

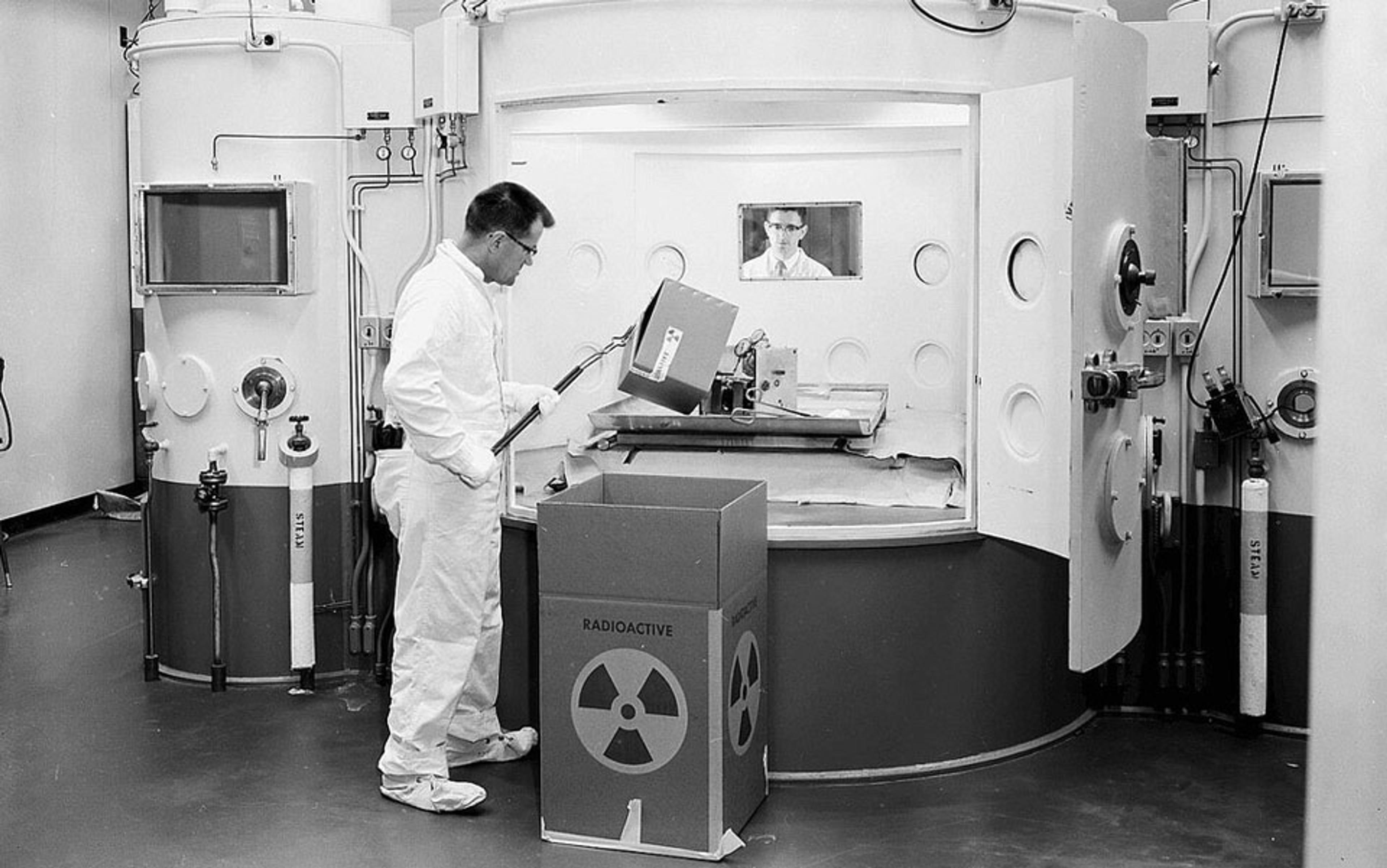

In the last decades of the 20th century, lawyers representing manufacturers had created a highly restrictive set of court rules dictating the evidence necessary to prove damages from environmental contamination. Scientists drawing on American-directed studies of Japanese bomb survivors narrowed the field of inquiry to a few carcinomas and thyroid disease. Downwinders, however, connected their sheep born without eyes to birth defects in their children. The thyroid study did not address genetic effects, or many other health problems that Russian scientists discussed in medical literature as ‘chronic radiation syndrome’.

Taking his lead from the study, the US district judge Alan McDonald severely limited the number of claimants in the downwinder case. He ruled that, to be eligible, plaintiffs had to prove they had received a dose of radiation high enough to cause twice the number of cancers that would occur in the population at large.

During the heated debates that followed, the science of ‘experts’ was often pitted against local knowledge wielded by farmers and ‘lay people’. In angry meetings in eastern Washington, scientists pulled out charts and graphs showing how impossible it was that anyone had been harmed by the plant: ‘on average’, they were well within permissible doses. Locals replied that what the scientists said made no sense, that in their communities they could pinpoint the places where most people had health problems. The scientists discussed ions, rads and isotopes. They clashed with people who wanted to talk about their loved ones’ immune disorders and tumors. The dry, bristling Seattle-based experts reminded many people of the arrogant Hanford scientists, whom the downwinders believed had caused their problems in the first place.

It isn’t that one form of knowledge, expert or local, was right and the other wrong. Both local and expert knowledge were limited and reflected diverging interests. Because the record of ingested and ambient radioactive isotopes was nearly impossible to trace backward in time, both forms of knowledge were, in the end, circumstantial. In court and congressional hearings, however, science wielded by experts was seen as ‘objective’ and ‘disinterested’, while women tallying up their sick children and neighbours were labeled ‘subjective’ and ‘anecdotal’.

How did Bailie, with his high-school education, come to the same conclusions as an army of Hanford researchers with multi-million dollar budgets?

As the case dragged on, Bailie staked his social capital on proving that the plutonium plant had caused his parents’, aunts’, uncles’ and sisters’ cancers, and possibly his own birth defects and infertility. As a child, he told me one night over dinner, he had long stays in the Hanford-funded hospital where he was put in an iron lung for a mysterious paralysis. He remembered a strange blue light, the door to a ward guarded by soldiers, and being awakened to shouts. When he asked the nurse what was wrong, she hushed him, saying: ‘Go back to sleep. Those are just the men from Hanford.’

I never knew what to make of Bailie’s stories. As he spoke, I’d often have a vertiginous sensation that I’d entered the studio of a midnight talk radio show and wasn’t allowed to leave. Sometimes uncouth and usually inappropriate, he would ramble from conjecture to rumor to conspiracy. His stories were hard to follow and much, much harder to believe. A couple of journalists have said as much, one calling him a blowhard. Bailie might be the most oft-quoted unreliable narrator in American history.

He knew he didn’t sound credible. ‘I’m a kid, they give us milkshakes and pass a meter over our stomachs; there’s a naval base in landlocked Pasco. My friend’s father who runs the train depot is really, my friend tells me, an FBI agent, and no one around here but me seems to think all this is strange.’

Unreliable narrators are often worth listening to. There are some truths that most people don’t believe, not because they are not true but because, like the mythical prophet Cassandra, society is resistant to them. So I seek out unreliable narrators and then cross-check the facts.

Almost everything Bailie told me panned out.

In the early 1960s, scientists did collect samples from local farms and took ‘bioassays’ of wild game and livestock. They tested the drinking water and collected bovine thyroids from slaughterhouses in the towns of Pasco, Mesa and as far away as Wenatchee. From 1949, Hanford researchers also harvested the organs of plutonium workers and workers on neighboring farms. Investigators funded by the Atomic Energy Commission secretly gathered bones of children worldwide to measure radioactive fallout. The Richland hospital did have a guarded ward with cement-lined rooms, to protect staff from the bodies of patients too radioactive to go near. Twinkies and poor diet might indeed have helped Bailie. Hanford studies showed that people who ate food purchased in grocery stores had lower counts of radioactive by-products. Another study showed that pigs on poor feed retained fewer radioactive isotopes than those on healthy diets.

Bailie’s guess that farmers living on the hills had more exposure than those below also fitted with the Hanford researchers’ descriptions of plumes of radioactive iodine heading ‘upslope into the valleys’. Over the years, Bailie tipped me off about plant accidents. He gave me little lectures on topography, soil qualities and the path of radioactive particles through a digestive track. ‘But what do I know?’ he would say at the end of his monologues. ‘I’m just a dumb farmer.’

He had a point there, too. How did he, with his high-school education, bouncing around country roads in a battered Chevy, come to the same conclusions as an army of Hanford researchers working on classified studies with multi-million dollar budgets?

Science understands complex processes by simplifying them. Radiation pathway studies were based on models, averages and aggregate populations, with a streamlined view of single isotopes entering the body through singular routes. But radioactive effluents don’t really spread through environment as a generalised statistical aggregate. In reality, they collect at random points because air currents, river eddies and groundwater follow idiosyncratic patterns to deposit fission products unevenly across the land. At these hot spots, bodies were drenched in fission products, not at average levels but at great intensities.

Scientists breezing in from Seattle had only a cursory grasp of the hot spots, which is not surprising. To determine where and how hot they were, they would have had to go over the exposed 75,000 sq mile territory inch by inch, measuring in three dimensions: plants, roots, soil, ground water and cubic air vertically up to 2,000 feet. They would have had to know the land the way children know the back lot, the way a farmer understands the nutrients of his soil, the drainage, dips and turns of a field, the vagaries of wind and weather.

To do a thorough epidemiological study, the scientists would have had to get to know the population on intimate terms, not just the people living there but also those who had moved or died. It would take knowing who had had a miscarriage, who was sick with what, which couples had trouble with fertility, which kids were somehow just not right. In short, it would require the kind of knowledge people in extended families or close-knit communities possess. The Hanford and Seattle scientists, sequestered by day on the nuclear reservation, often transplanted from elsewhere to the lab headquarters in Richland where they were seen as arrogant and socially isolated, did not have that kind of knowledge.

As the community divided into people who backed the plutonium plant and those who suspected they had been poisoned, Bailie became a lightning rod

But Bailie did. He carried around folders of clippings and documents, and he put that information to work alongside his farmer’s understanding of local history, geography, geology and climate, mixed in with gossip, rumor, family lore and coffee-shop conjecture. He talked to every reporter who called him until his wife just about divorced him. A lot of fellow farmers wished that Bailie would shut up before their crops were stigmatised as radioactive and lost value. As the community divided into people who backed the plutonium plant and those who suspected they had been poisoned, Bailie became a lightning rod. Lots of people, including friends and family, stopped talking to him. He suddenly had trouble extending his credit lines at the town bank, and he lost his farm.

Meanwhile, the downwinders’ lawsuit was languishing in court. Delaying the case again, Judge McDonald told the press that ‘the government’s limited resources should be focused on [nuclear] clean-up and not diverted by litigation’. Ten years passed with no hearing, then another five years. The defence had good reasons to postpone the case. The federal government was committed to covering all legal fees for the five former contractors being sued, so corporate defence lawyers had no motivation to settle out of court or resolve the issue speedily. The Chicago law firm, Kirkland and Ellis, racked up $28 million in legal fees, all of it bankrolled by taxpayers. Downwinders, on the other hand, had neither time nor deep pockets. Many plaintiffs were elderly or sick. They struggled with medical bills and their lawyers worried over the mounting legal costs. To top off the injustice, in 2000 the federal government agreed to pay up to $150,000 each to former Hanford employees with radiation-related health problems. Downwinders were exasperated to see that while their claims were denied, workers who had submitted to the risks and secrecy of making plutonium got a payout. The whole process felt like a fix.

Rather than concede defeat, the downwinders did something remarkable. They took the burden of research into their own hands. Several activists convinced the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to review the original thyroid study, which had found no significant health effects among downwinders. The CDC determined that the thyroid study researchers had overstated their conclusions, underestimating the population’s doses, and that, in fact, the subject population had three times more cases of thyroid disease than expected. These contradictory assessments made sense when the downwinders discovered that lawyers for the defence firm had sat in on the first meetings of the original dose reconstruction study in order to design the study for ‘litigation defence’. The downwinders also learned that Judge McDonald owned an orchard directly across the river from Hanford. Acknowledging that his agricultural holdings could decline in value if a jury found Hanford hazardous, the judge finally had to recuse himself.

The downwinders embarked upon a new kind of people’s epidemiology. Joining forces with doctors, scientists and social justice advocates, they devised a health survey that they distributed to friends, neighbors and family members in grocery stores and churches. They canvassed anyone who might have been exposed to internally ingested radioactive isotopes. The survey asked about the kind of specific factors — family health, diet, landscape, and wind patterns — that might contribute to localised exposure to radiation. Analysing the results from 800 completed surveys, the downwinders compared disease rates with those among a control population. They found the affected population to be six to 10 times more likely to have thyroid disease and other illnesses. The community-based study contradicted the original government-funded reports, but its results squared with tests that Hanford scientists had run on animals over the years, and that Russian scientists had conducted on populations exposed to the Mayak plutonium plant in the southern Urals. Perhaps no less importantly, the downwinders’ epidemiology validated people’s knowledge about their health and landscapes. That felt good after a decade of being told they were wrong and ignorant.

In 2009, Bailie took me to his high-school reunion. The class of 1968 was meeting at Michael’s Café in downtown Connell, less a town than a strip off the highway. It has a hotel, a state prison, a food processing plant, and a string of mobile homes. Twenty-five years had passed since locals learned of Hanford’s dangerous emissions. Even so, as we went in, Bailie said it wouldn’t be a good idea to mention thyroid or health problems. ‘People don’t want to talk about that.’ He looked nervous, perhaps expecting to get dressed down for bringing a snooping historian to the class reunion.

While he went off to greet old friends, I sat down at a table and prepared to make small talk. I didn’t get a chance. Pat rolled up in a wheelchair. She told me she had multiple sclerosis, as did her sister. She said she used to pick peaches down in Ringold, across the river from the plant. She attributed her illness to Hanford. Linda chimed in that her mother had troubles with her thyroid. Her father, always slim and active, had heart problems very young. Crystal (thyroid and lung cancer, never smoked) said she never bothered with that downwinder business on account of her own health problems, but when her daughter got cancer and was diagnosed infertile, that made her angry. Gwen (thyroid disease) didn’t look well. Her husband had to heave her from her walker to a chair. The classmates all grew up on land opened in the early 1950s for irrigation, farms just downwind from Hanford. They talked about the green books the scientists gave them in the 1960s to record every bushel of wheat and pound of potatoes. All that crazy detail, they laughed.

Bailie joined us and turned to Gwen. ‘Remember how your mother used to say she didn’t feel well because of the water? And your father used to say: “You’re crazy, woman! That is a 1,200 foot artesian well.” Remember that?’ Bailie asked. ‘No one knew then that we shared an aquifer with Hanford’s leaking waste tanks. We all drank from that aquifer.’ Becoming agitated, he pulled out a dinner napkin and drew a line marking a country road. He made an X over the Holmes’ farm. ‘She got bone cancer. The girls both had thyroid problems.’ His pen turned a 45-degree angle. ‘She drowned her deformed baby in the bathtub and then committed suicide.’ Bailie marked out two more farms: ‘She had leukemia, and up there the baby was born with no head.’ Bailie stopped at Gwen’s farm. Gwen’s mother died of leukemia in her 40s. Her father also died of cancer. Gwen had a lifetime thyroid condition (and died a few years after the reunion). ‘That’s what we used to call the death mile,’ he said.

A man walked up to our table. He’d had a few drinks. His eyes were red, his speech slurred. He said Bailie was full of bull. He had grown up on a downwind farm and he was fine. ‘We have plenty of 87-year-olds around here.’ Bailie nodded and blinked, abnormally silent. The other classmates stared at their laps. I was surprised. I’d never known Bailie to back down from a debate. Later he told me that the interloper suffered from serious health problems. ‘I couldn’t argue,’ he said. ‘I felt sorry for him.’

Bailie had been reviled in his community. In his obstinate refusal to stop talking, he pointed out how some truths, visible to the naked eye, had been overlooked, while silences had begotten certainties. By 2009, there was only one drunken man at the reunion left to question him. Those crazy stories he had been telling for decades no longer sounded so crazy.

Before Bailie and other downwinders started talking, there had been no real debate about Hanford’s health effects. Instead, there was an appearance of scientific debate that washed out in an often-calculated confusion and uncertainty. Until the downwinders started making a noise, there was no debate because there were no sick people. Sick Hanford workers, sick farmers and sick neighbours silently suffered alone for years, never realising they shared a fate with thousands of others.

In the years after Chernobyl, as the downwinders talked, met, campaigned and traveled to Japan, Ukraine and the southern Urals, they came to learn of multitudes like themselves. The diseased bodies of self-proclaimed downwinders helped to map the invisible geographies of contamination, hidden for decades in the interior American West. Using their own bodies as evidence, they pointed to the gaping contradiction in the claim that, while the nuclear reservation itself was deemed dangerous enough to require more than $100 billion to clean up, the people living next to the reservation were safe. In their frustration at experts used to zoning territory into ‘clean’ and ‘contaminated’ and compartmentalising information based on laboratory procedures, the downwinders created alternative ways to produce knowledge.

And it paid off, at least to a point. A schedule of cases in various classes (thyroid cancer, thyroid disease, hyperthyroidism and ‘other’) is now working its way through the legal system. Trials are planned for 2013. In 2005, plaintiffs won two of six bellwether cases for thyroid cancer, and had the other four cases reversed on appeal. Based on that success, downwinders won some leverage in settling out of court. Most payments, however, are tied to dose estimates that are still highly contested, and the settlements are very small ($2,500-$150,000). They come nowhere close to covering medical and legal bills.

Is it a victory, then? Lawyers for the defence and for the plaintiffs both claim they’ve won. Kevin Van Wart, the lead counsel for Kirkland and Ellis, says that by halving the original 5,000 plaintiffs they saved tax-payers from funding cases that should never have gone to court. The downwinder lawyer Richard Pierson believes that his clients have the victory because the Department of Energy has finally acknowledged the need to settle with payouts. Officials can no longer claim that there was no connection between Hanford pollutants and the downwinders’ thyroid conditions.

Meanwhile, Tom Bailie, who lost his own farm, drives a truck in his nephew’s fields for minimum wage. For him, for now, this small triumph will have to suffice.

Excerpted from Plutopia: Nuclear Families in Atomic Cities and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters by Kate Brown. Copyright © 2013 by Kate Brown, published by Oxford University Press US, April 2013. Reprinted with the permission of the Author, all rights reserved.