Listen to this essay

29 minute listen

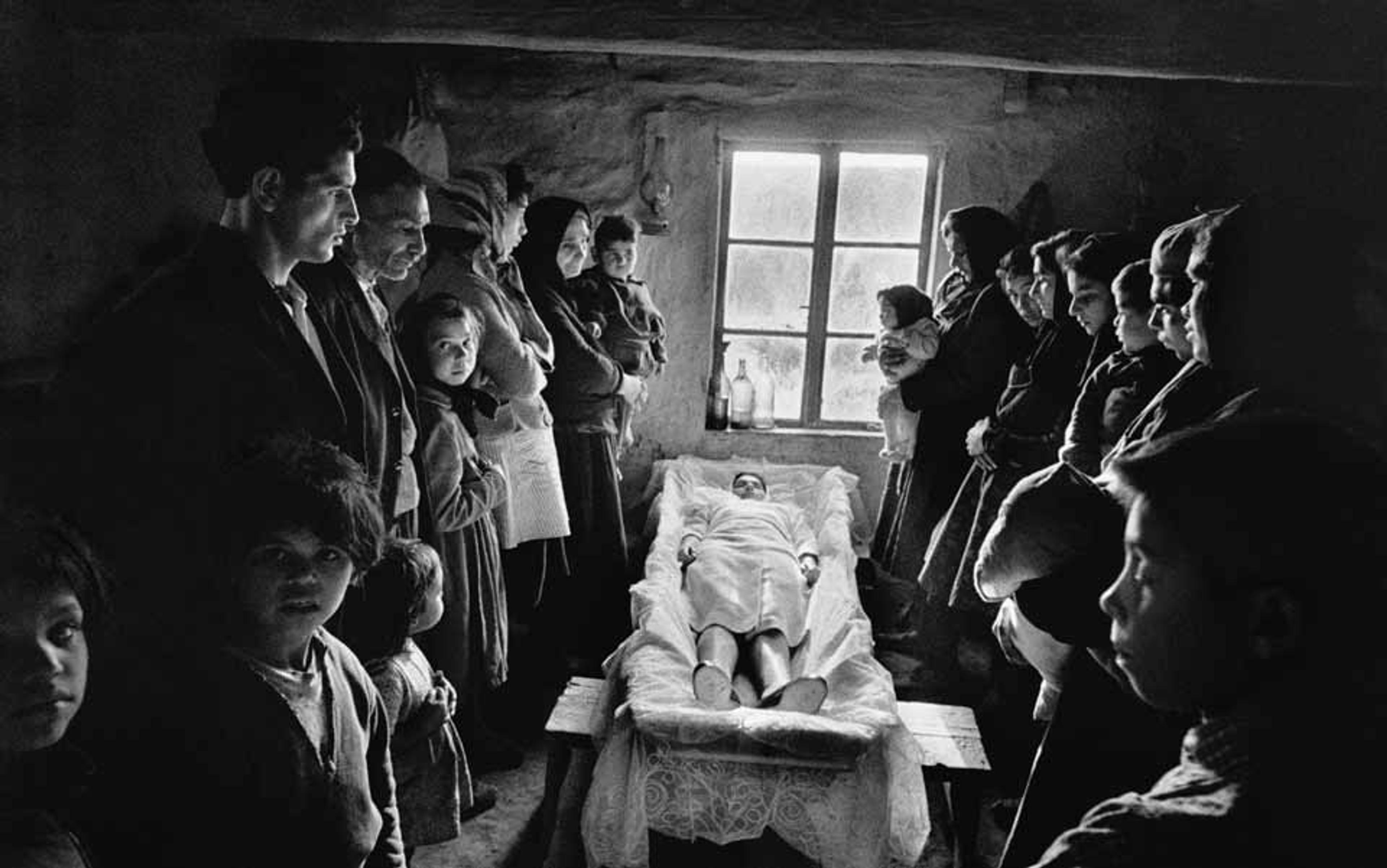

‘When I consider the short duration of my life,’ wrote the 17th-century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, ‘I am frightened.’ Human history is riddled with such examples of our struggle with mortality, from ancient mortuary practices intended to grant safe passage through an uncertain afterlife, to the uncountable stories of loss that fill our libraries. As René Girard observes in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978), human culture itself arises from the brute fact of our ending: ‘There is no culture without a tomb and no tomb without a culture; in the end the tomb is the first and only cultural symbol.’ Death, it seems, has always been a problem for us.

Yet in the past decade, human mortality has become newly troubling in unexpected ways. Each year, roughly 3.6 billion kg of human flesh and bone must be disposed of worldwide, and it is becoming clear that the dominant methods we rely on for that task – burial and cremation – significantly impact the Earth. For example, the emission of nitrogen oxides during a single cremation is roughly equivalent to driving a car almost 3,670 km. Human death and human remains – not only human life and livelihoods – may now be contributing to planetary decline, a problem intensified by anthropogenic climate change. These conditions have given rise to what Tony Walter, emeritus professor of death studies at the University of Bath in the UK, calls ‘a (new) death mentalité’. That is, a new shared attitude in which our attention has shifted from the loss of individuals or communities to ‘species extinctions on a scale hitherto unknown during homo sapiens’ time on Earth.’

The problem of death seems to demand different answers – new methods. And now, you can take your pick: would you like to become a tree? Perhaps you would prefer to transform into soil? Maybe you’d rather feed a microbial network?

These are some of the ecological afterlives promised to those in search of a ‘green death’. In the past two decades, funeral directors, cemeteries and start-ups in the UK, the US and other parts of the Western world have begun offering a range of ecologically friendly options for body disposal, marketed with organic aesthetics and lush imagery. These options envision different returns to nature – imagine shrouded bodies decomposing in rich, moss-covered soil under sprawling tree canopies.

In recent years, interest in green death has surged in the West, as the human impact on the Earth has become clearer. Far from a destructive or polluting act, human burial is being reframed as a chance to mend our relationship to nature. The dream of green death is that of a gentle end: a death that is aesthetically beautiful, nourishes the planet, and restores community. Composting your remains or allowing your dead body to feed a tree seem like noble responses to the problem of our toxic bodies – a way to participate more fully in the flourishing of future life on our planet.

However, closer examination of contemporary eco-death technologies reveals that this dream is not so easily realised. It remains plagued by a lack of reliable empirical evidence, inflated corporate claims, and unequal access to new technologies. Can we truly hope to die green? Or is it all just greenwashing?

In 1993, a forward-thinking bereavement services manager in Cumbria, England, named Ken West responded to requests from people asking to be buried among the 20 acres of wildflowers that had been planted on a cemetery where he worked. With this decision, Carlisle Cemetery in Cumbria became the first place to commercially offer a natural ‘woodland burial’, in which bodies were interred in soil without technical interventions that would hinder decomposition, such as embalming. The goal was to create a kind of nature reserve with no headstones or non-biodegradable ornaments. In place of these memorials, family members planted saplings (mostly oak trees). Each spring, beneath the growing trees, the cemetery ground would fill with snowdrops, daffodils and bluebells. In this way, burial became a return to nature, whereby decomposing corpses would bestow a final nutrient gift to other forms of life.

Such green death practices are nothing new. In fact, they are really the first forms of body disposal, from the time when many of our ancestors dug shallow graves or left bodies exposed to the elements and scavengers. An openness to decomposition continues in many traditions: consider the widespread use of biodegradable shrouds rather than coffins in Islamic and traditional Jewish burials. The woodland burials at Carlisle Cemetery are an extension of these earlier practices. But in the context of the Western funeral industry, and its fixation on slowing decomposition, such approaches can still appear innovative – even radical.

A dominant narrative is that decomposition is a return to nature, and should be reframed as positive

At the turn of the 21st century, green death practices expanded. They appealed as technical solutions for handling the disposal of human remains, but also as new ways of envisioning the dead human body, its value and relationship to the Earth. Today, though the green deathcare movement remains largely in its infancy, there are thousands of providers around the world who offer these kinds of burial options.

One dominant narrative promoted by such providers is that death and decomposition constitute a return to nature, and that this return should be reframed as something positive. As Caitlin Doughty, a mortician from the ‘death-acceptance organisation’ The Order of the Good Death, said in 2011: ‘If we work towards accepting, not denying, our decomposition, we can begin to see it as something beautiful. More than beautiful – ecstatic.’ In some cases, this revaluation of decomposition adopts quite direct scientific language, describing the processes by which our bodies break down as we gradually disappear into the surrounding earth.

Occasionally, a ‘return to nature’ is facilitated by water, not soil. Some funeral companies offer alkaline hydrolysis – variously known as resomation, aquamation, or water cremation – which reduces the body to its basic components via an alkali-based solution that can be heated up to around 160 degrees Celsius. As with cremation, the resulting bones are then crushed into ash, while the residual fluid is released into the wastewater treatment system.

Alkaline hydrolysis was first developed for use in the funerary context in the 1990s and has since been marketed as the most environmentally friendly way of dealing with human remains. Indeed, this was a primary motivation for its choice by the archbishop Desmond Tutu following his death in 2021. But there are many other reasons why alkaline hydrolysis appeals, including cost and perceived gentleness.

More recently, ‘woodland burials’ and alkaline hydrolysis have been joined by a host of new green death technologies that promise ecological afterlives in the form of compost, mushrooms or trees.

One such technology is natural organic reduction (NOR), known commercially as terramation or recomposition. This form of ‘human composting’ involves placing bodies in a vessel between layers of woodchips, straw and alfalfa. Over the course of several weeks (if not months), microbes decompose the body to produce humus, the organic matter in soil. This humus is then removed from the vessel and ‘cured’ in the open air for several weeks. Throughout the process, the remains may be agitated, and bones and teeth crushed.

Like alkaline hydrolysis, NOR has its origins in the agricultural industry – both were used in the disposal of farm animals. The first facility to use NOR on human remains is run by the Seattle-based company Recompose, which opened in 2020. Its founder, Katrina Spade, spearheaded the legalisation of the technique for use in the US funeral industry.

The egg-shaped vessel would house a human corpse as it decomposes underground, feeding nutrients to support the life of a tree above

By transforming the dead into soil, Recompose promises the deceased and their families the chance to make a positive contribution to nature. Calling the process ‘Life After Death’, this is how the company describes its approach:

Healthy soil is vital for an ecosystem to thrive. It regulates moisture, sequesters carbon, and sustains plants, animals, and humans.

… Recompose was born from research on the soil cycle. Soil created by Recompose will nurture growth on the same forest floor that inspired its creation, allowing us to give back to the earth that nourishes us all our lives.

Trees, however, seem to be even more powerful metaphors for ‘nature’ than soil. The desire to live out an arboreal afterlife is expressed in a range of new technologies and services available globally – a continuation of the ‘woodland’ burials offered at Carlisle Cemetery.

Mornington Green in Australia, situated on 126,000 square metres of land reclaimed from a golf course near Melbourne, is a memorial garden offering the dead and their families the opportunity to become a tree through the interment of cremated remains under established saplings. Unlike many other funeral organisations offering an ecologically friendly form of burial, Mornington Green promotes the idea that individual personhood can be extended posthumously. The company does this by weaving the personal character of the deceased with the qualities of the tree that grows from their remains. There are a range of options, including Australian natives and exotic European species, presented in a manner that anthropomorphises each tree’s unique attributes. The ginkgo is described as ‘tenacious and hopeful’; the trident maple is ‘unique and strong’; and the flame tree is ‘charismatic and passionate’. The Mornington Green website even invites people to take a two-minute quiz to ‘find out which tree reflects your personality’, based on lifestyle questions about one’s ideal season, holiday destination, or Sunday afternoon activity.

Capsula Mundi. Courtesy Capsula Mundi

A similar burial technique, perhaps the most romantic of all, is Capsula Mundi, a biodegradable pod that has captured the global imagination in reporting on green death. Though not yet ready for widespread use, this egg-shaped vessel is intended to house a human corpse as it gradually decomposes underground, feeding nutrients to support the life of a tree above. Inside, a corpse would be curled in a fetal pose, forging a symbolic link between death and the regeneration of life, evoking continuous cycles of rebirth. As the Capsula Mundi website intimates: ‘Life is forever.’

Many green death technologies appeal for reasons beyond their environmental credentials, for example their cost, simplicity or convenience. They also offer powerful and appealing narratives that can help us make sense of the mystery of death in the absence of religious beliefs. If we don’t believe in an afterlife in some metaphysical sense, there is comfort to be found in the idea of returning our biological elements to the natural world and becoming part of some greater whole. Think of the astronomer Carl Sagan’s reflection: ‘The cosmos is also within us. We’re made of star-stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.’

A strong connection with nature and an awareness of our interdependence with it is becoming a prevalent worldview and a source of meaning for many. In his book A Brief History of Death (2005), the anthropologist and theologian Douglas Davies sees this kind of thinking as a form of ‘secular eschatology’ – a concept that religious studies scholars have elsewhere called ‘dark green religion’, ‘reverential naturalism’ or ‘relational naturalism’.

Folding our bodies back into the Earth, new death technologies are methods for absolving our ecological sin

Belief in a god or the supernatural is not necessary for making deep meaning around death. Rather than reciting verses from the Bible, secular funeral services at green burials might instead use Aaron Freeman’s ‘Eulogy from a Physicist’. The final lines read: ‘According to the law of the conservation of energy, not a bit of you is gone; you’re just less orderly. Amen.’ The green death company Recompose even offers their own naturalist ‘carbon cycle’ funeral service, in which staff verbally remind mourners that the molecules of their deceased loved one will be ‘transformed and incorporated back into life’.

So, there are many good reasons why someone might desire a green death. Increasingly, however, a return to nature is framed within the context of grand planetary shifts. For example, the US-based tree-burial company Transcend claims that their natural burial method has emissions savings equal to a ‘100 per cent reversal of your lifetime carbon footprint (based on global averages)’. Green death appears to be a direct means of reducing, or even absolving, the guilt of contributing to anthropogenic climate change. That is, by folding our bodies seamlessly back into the Earth, new death technologies are presented as methods for absolving our ecological sin.

But a closer examination of the available scientific evidence points to deeper complexities beneath the surface of green death. Perhaps our fantasies of returning to nature say more about our desire to feel redeemed than our genuine concern for damaged ecologies.

Those who promote green death technologies often make overtures to the environmental credentials of their services through comparisons with ‘conventional’ forms of burial and cremation. According to Transcend, their tree burials are ‘576 per cent more sustainable than cremation’. One Australian alkaline hydrolysis company claims their service ‘uses less than 10 per cent of the energy of a traditional fire cremation’. The UK start-up Cryomation says their method of using liquid nitrogen to freeze bodies and turn them into a powder has ‘a 70 per cent lower carbon footprint than Cremation’. And in a section on Recompose’s website titled ‘Healing the Climate’, the company states: ‘For every person who chooses Recompose over conventional burial or cremation, one metric ton of carbon pollution is prevented. In addition, our approach to human composting uses 87 per cent less energy than conventional burial or cremation.’

There are many good reasons to be sceptical of these ambitious claims.

To begin with, some of the most frequently discussed green death technologies are simply not possible. This includes Capsula Mundi, which to date has never successfully been used for whole-body burial, despite a marketing campaign that has led many to assume the pods are already viable. Instead, similar devices are currently being sold as urns for cremated remains. Another example is cryomation, which purportedly involves freezing a dead body in liquid nitrogen at a temperature of -196 degrees Celsius. The body is then shattered into small fragments, freeze-dried, and buried in a biodegradable container, which decomposes over 12 months. The process is said to reduce the total amount of matter that needs to be buried compared with many other kinds of burial, thereby freeing cemetery space. The process, initially called promession, was first advocated for by a Swedish company, Promessa Organic AB, which never managed to proceed to human trials. The technique has now been taken up by the UK company Cryomation, which has received significant funding from a range of sources – the European Commission, Innovate UK, Shell – without ever launching a commercial prototype.

None of the companies listed have shown how they arrived at the statistics they are sharing on their websites

Even the green death solutions that are possible are not always accessible or even legal in all locations worldwide. This means that being composted or hydrolysed to ease the environmental burden of your death could require travelling tens of thousands of kilometres unless you’re lucky enough to live in one of the US states where human composting is legal or alkaline hydrolysis is commercially available. Neither technology is widely available outside of a small handful of select providers in the UK, Australia, South Africa, Canada and Ireland. Natural burial grounds can be similarly scarce, and the emissions required to transport dead bodies long distances to access them means that they can’t always function as a green choice.

The companies that promote green death technologies generally provide poor evidence to support their claims. None of the companies listed above have shown how they arrived at the statistics they are sharing on their websites. It remains unclear how companies calculate the environmental impact of conventional burial and cremation, let alone composting, natural burial, alkaline hydrolysis or cryomation. Some companies make reference to pilot research studies or internal trials, but neither raw data nor analyses have been made publicly available.

It does not appear that any independent authority or regulatory body is yet providing advice to consumers about the veracity of such claims or preventing companies from making them. As such, it is incredibly difficult for journalists and academics to assess the relative effectiveness of these techniques. And for the dying and bereaved seeking greener forms of deathcare, making sense of all of this is nearly impossible.

There are still very few peer-reviewed, independent studies that assess or compare the overall environmental impact of new burial technologies. Two peer-reviewed reports were published in 2011 and 2014 by the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research, an independent research organisation. These reports, which present an environmental impact life-cycle assessment of different burial options, determined that the best techniques were, in order of effectiveness, alkaline hydrolysis, cryomation, and cremation. Traditional burial was rated as the least environmentally friendly option.

However, these reports are now more than a decade old and do not consider significant recent developments, including human ‘composting’ methods. The reports are also specific to the context of the Netherlands and not easily generalisable worldwide. A more recent report from 2023, conducted by the UK sustainability certification company Planet Mark, takes an in-depth look at the environmental impact (ie, carbon emissions) of different ‘body disposal’ options and coffins. Again, alkaline hydrolysis was determined to be the most sustainable burial method. But the authors also make some controversial assumptions in the process of judging carbon emissions. Against the advice offered by the report’s own experts, they suggest that graves in natural burials are excavated manually rather than by machines – excavating by hand, however, is very rare. The report also excludes certain data points, such as effluent from alkaline hydrolysis, due to a lack of independent evidence.

What of the catering, imported flowers, marble headstone, and visitors attending the funeral or grave from afar?

This research shows how complicated it can be to declare one body-disposal method the ‘greenest’. A method might perform well in one category (such as carbon emissions) but poorly in another (such as water consumption). It might perform well in one location but not another. And there can be hidden environmental impacts built into a specific technology’s supply chain or its real-world application. For example, it’s hard to determine the emissions associated with growing the necessary alfalfa, straw or other organic matter used for human composting in NOR. Even alkaline hydrolysis, typically identified as the most ecologically friendly method, has uncertainties: researchers rarely consider the emissions involved in transporting the deceased to a facility that offers this form of burial. In most cases, a crematorium or cemetery will likely be much closer.

This last point is important. Body decomposition itself makes up only a small fraction of the total environmental impact generated by activities surrounding a death. What of the catering, imported flowers, marble headstone, and visitors attending the funeral or grave from afar? As the PlanetMark assessment report concludes: ‘recurrent visits to the final resting place has a much higher impact over the years than any of the disposal methods.’

For this reason, it is perfectly plausible for a relatively polluting option, like natural gas cremation, to end up with a smaller environmental footprint than something promoted as a green burial.

Ultimately, everything we do in relation to death pales in comparison with the environmental impact of our lives. As the Dutch report of 2011 notes: ‘the relative value of the environmental impact of funerals, however, scores low in all effect categories compared with the resource use and emissions of one year of life of an individual.’

Looking closely at the available research can lead to serious doubts about environmentally friendly ways to die.

Regardless of how environmentally friendly new burial practices really are, there are many reasons why a green death remains desirable. Becoming a tree or returning to earth provide a meaningful narrative to help people make sense of their mortality and place in the cosmos. And visions of death and decomposition as something peaceful, regenerative and even beautiful are equally appealing. The danger and greenwashing arise when the environmental credentials of burial methods are inflated.

There are larger concerns, too. The focus on individual choices – should I become a tree, compost, liquid or a microbial network? – is a market solution that distracts us from what we could be doing on a collective scale to make death greener. The real task falls to government regulators and the funeral industry, not the bereaved. And it involves work that is often unromantic.

The burden of planetary repair is shifted onto individuals and families during a period of profound vulnerability

Simply improving existing facilities can sometimes be more effective than looking for new solutions. This may involve imposing standards for increasing efficiency across the entire sector, such as installing nitrogen oxide and mercury abatement equipment in crematoria, which help to reduce the negative environmental impact of cremation emissions. There are a range of other changes that could help existing ‘traditional’ cemeteries, including introducing restrictions on the international importation of granite for headstones, increasing the recycled materials used in concrete, and relying on electricity rather than gas for vehicles and crematoria. These approaches would also allow for environmental concerns to be balanced against other sector-wide challenges, including the protection of deathcare workers who are often stigmatised for their work, poorly renumerated, and vulnerable to significant occupational health and safety hazards.

Unfortunately, none of these options conjure the same appeal as new green death technologies – and that appeal is undeniable. It promises to make our final act ethical, restorative and spiritually resonant. Death becomes a way to reimagine ourselves as participants in ecological renewal rather than contributors to planetary harm. But danger arises when this dream eclipses scientific and regulatory realities. And what about greenwashing? It appears when poetic imagery stands in for evidence, when technological optimism obscures the much larger environmental impact of a life, and when the burden of planetary repair is shifted onto individuals and families during a period of profound vulnerability.

What would it mean, instead, to align the art and the science of death – to cultivate rituals that acknowledge our entanglement with damaged ecologies while demanding rigorous, sector-wide reform? A genuine ecological approach to death would not ask the dying or grieving alone to atone. It would require rethinking the infrastructure of deathcare itself: the energy systems that power crematoria, the materials that are made into funerary goods, the regulations that govern emissions, land use, and human labour conditions. Only when our stories of renewal and return are matched by transparent evidence and systemic change will green death become more than a consoling fiction. Only then can we claim to die in ways that do not merely soothe our anxieties, but that meaningfully lessen our trace on an Earth in disrepair.