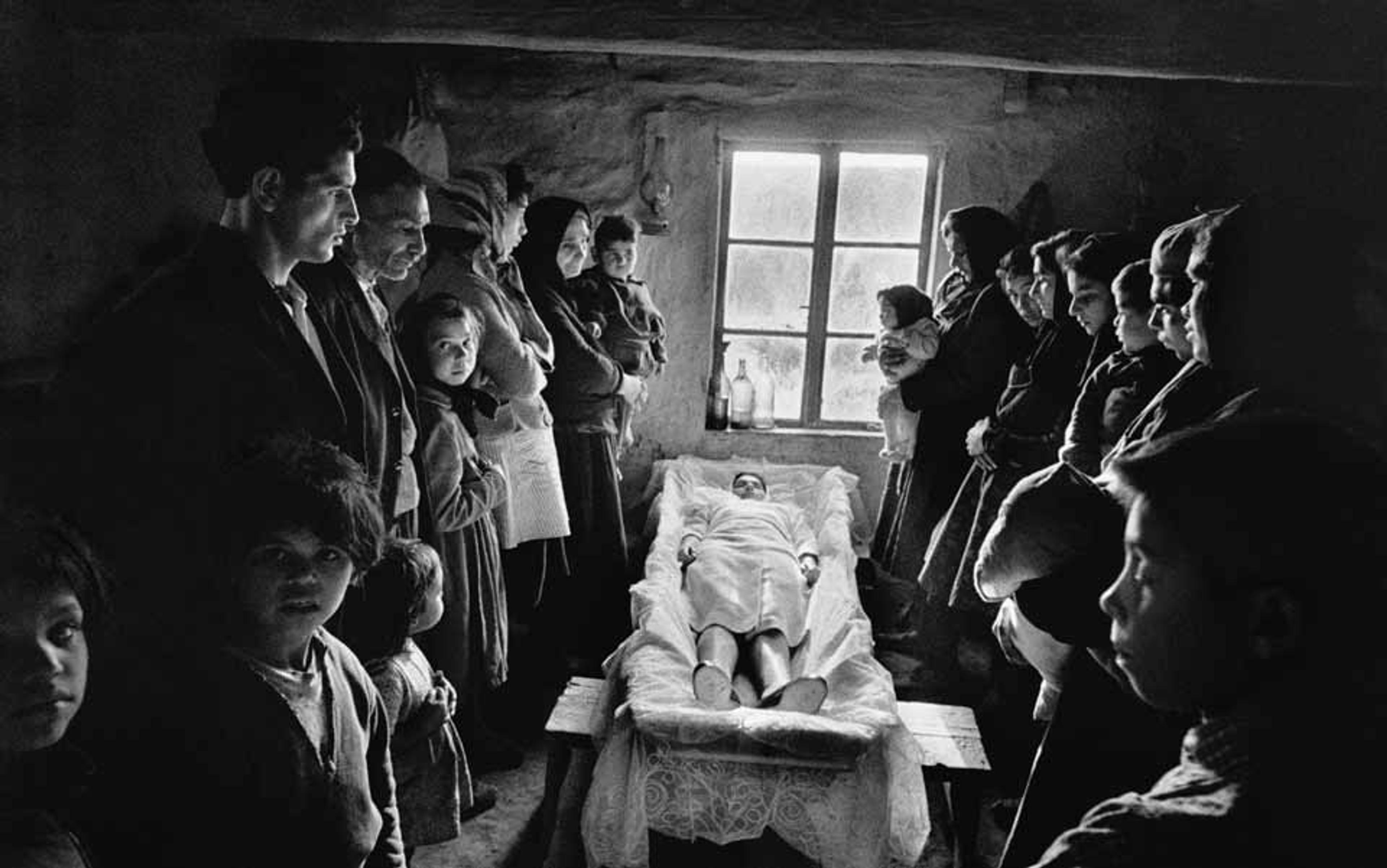

The first week of April 2005 was dominated by images of Pope John Paul II’s dead body vested in red, mitred and laid out among his people with bells and books and candles, blessed with water and incense, borne from one station to the next in what began to take shape as a final journey. The front pages of the world’s daily papers were uniform in their iconography: a corpse clothed in sumptuous vestments from head to toe, still as stone and horizontal. Such images, flickering across their ubiquitous screens no doubt gave pause to many Americans, for whom the presence of the dead at their own funerals had gone, strangely out of style.

For many bereaved Americans, the funeral has become instead a ‘celebration of life’. It has a guest list open to everyone except the actual corpse, which is often dismissed, disappeared without rubric or witness, buried or burned, out of sight, out of mind, by paid functionaries such as me — the undertaker. So the visible presence of the Pope’s body at the his funeral struck many as an oddity, a quaint relic of old customs. How ‘Catholic’ some predictably said, or how ‘Italian’, or ‘Polish’, or ‘traditional’; how ‘lavish’, ‘expensive’, or ‘barbaric’.

Instead, what happened in Rome that week followed a pattern as old as the species. It was ‘human’, this immediate focus on the dead and this sense that the living must go the distance with them. Most of nature does not stop for death. But we do. Wherever our spirits go, or don’t, ours is a species that down the millennia has learned to process grief by processing the objects of our grief, the bodies of the dead, from one place to the next. Whatever afterlife there is or isn’t, human beings have marked their ceasing to be by going with their dead — to the tomb or the fire or the grave, the holy tree or deep sea, whatever sacred space of oblivion we consign them to.

The formula for human funerals was fairly simple for most of our history: by getting the dead where they needed to go, the living got where they needed to be. By acting out the necessary tasks to rid ourselves of dead human bodies, we came to understand the meaning of death. The disposition of the dead inured us to the benefit of the living and so, unlike other living breathing, eating, breeding things that died and were ignored by others of their kind — cocker spaniels and rock bass, warblers and wombats — our kind has always felt somehow duty-bound to do something with, or for, or to, or about it. Even when it is not one of our own — a family dog, or pet rabbit, for instance — we construct sweet obsequies to make sense of those things we find hardest to put into words.

Ours is the species bound to the dirt, fashioned from it according to the Book of Genesis. Thus human and humus occupy the same page of our dictionaries because we are beings ‘of the soil’, of the earth. The lexicon and language is full of such wisdoms. Thus, our ‘humic density’, as the Dante scholar Robert Pogue Harrison calls it: the notion that everything human — our architecture and history, our monuments and cities, are all rooted in and rising from the humus, the earth, the ground in which our dead are buried — is what eventually defines us.

Years ago I took to trying to imagine the first human widow awakening to the dead lump of a fellow next to her, stone-still under the hides that covered and warmed them against the elements. This might have been 40,000 or 50,000 years ago, somewhere in the Urals, or Mesopotamia, or the Dordogne. Or maybe Lebanon, or Uganda, or the Congo, and 70,000 or 80,000 years ago. Our species’ history is a work in progress. Anyway — long before we had alphabets or agriculture, or any of the later-day civilizers. Our species evolved from upright foragers and carnivores to upright foragers and carnivores who start thinking in symbolic terms. They began to wonder. Symbol and image and icon and metaphor became part of their reality. What was it, I ask myself, that first vexed them into contemplations?

I always imagine a cave and primitive tools and art and artifacts. They have fire and some form of language and social orders. This first human widow wakes up to find the man she’s been sleeping with and cooking for and breeding with gone cold and quiet in a way she had not formerly considered. Depending on the weather, sooner or later she begins to sense that something about him has changed quite utterly and irreversibly. What makes her human is that she figures she’d better do something about it.

Perhaps she gathers her things together and follows the nomadic herd of her group elsewhere, leaving the cave to him, in which case we could call it his tomb. Or maybe she likes the decor of the place and decides that the now unresponsive and decomposing lump of matter next to her should be removed. She drags him out by the ankles and begins her search for a cliff to push him over or a ditch to push him into or maybe she digs a pit in the earth to bury him because she doesn’t want wild animals attracted to his odour. Or maybe she builds a fire, a large fire, around and atop his rotting body and feeds it with fuel until the body is consumed. Or let’s say she lives near a body of water and counts on the fish to cleanse his remains; or maybe she hoists him into a tree and figures the birds will pick him clean. Maybe she enlists the assistance of others of her kind in the performance of these duties – who do their part sensing that they might need exactly this kind of help in the future.

The bodiless obsequy has created an estrangement between the living and the dead that is unique in human history

It has to do with that momentary pause before she turns and leaves the cave, or the ditch or the pit or the fire or the pond or the tree or whatever she has chosen for him, and she stares into the oblivion she has consigned him to, and frames what are the signature questions of our species: Is that all there is? Why is he cold? Can this happen to me? What comes next? Of course, there are other questions, but all of them are uniquely human, because surely no other species ponders such things. This is when the first glimpse of a life before or beyond this one begins to flicker into our species’ consciousness, and questions about where we come from and where we go take up more and more of the moments not spent on rudimentary survival.

Contemplation of the existential mysteries, those around being and ceasing to be, is what separates humans from the rest of creation; our humanity is directly tied to how we respond to mortality. In short, how we deal with our dead in their physical reality and how we deal with death as an existential reality define and describe us in primary ways. This intimate connection between the mortal corpse and the concept of mortality is at the core of our religious, artistic, scientific and social impulses. As the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman writes in Mortality, Immortality and Other Life Strategies (1992):

No form of human life, however simple, has been found that failed to pattern the treatment of deceased bodies and their posthumous presence in the memory of the descendants. Indeed, the patterning has been found so universal that discovery of graves and cemeteries is generally accepted by the explorers of prehistory as the proof that a humanoid strain whose life was never observed directly had passed the threshold of humanhood.

And this formula — dealing with death by dealing with the dead — defined and described and, by the way, helped humans for 40,000 or 50,000 years all over the planet, across every culture until we come to the most recent generations of North Americans who for the past 40 or 50 years have begun to avoid and outsource and ignore their obligations to deal with the dead. They are willing enough to keep ‘their presence in the memory of descendants’ (the idea of the thing), so long as they don’t have to deal with ‘the treatment of deceased bodies’ (the thing itself). A picture on the piano is fine but public wakes, bearing the dead to open graves, are strictly out of fashion.

While this estrangement is coincident with the increased use of cremation, and might be correlated to it, cremation is not the cause of this estrangement. Indeed, cremation is an ancient and honorable and effective method of body disposition, but in most cultures where it is practised it is done publicly in ceremonial and commemorative venues, whereas in North America very often it is consigned to an off-site, out-of-sight, industrial venue where everything is handled privately and efficiently. Only in North America has cremation lost its ancient connection to fire, because it is so rarely actually witnessed. In the past 50 years, cremation in North America has become synonymous with disappearance, not so much an alternative to burial or entombment, rather an alternative to having to bother with the dead body.

The bodiless obsequy, which has become a staple of available options for bereaved families in the past half century, has created an estrangement between the living and the dead that is unique in human history. Furthermore, this estrangement, this disconnect, this refusal to deal with our dead (their corpses), could be reasonably expected to handicap our ability to deal with death (the concept, the idea of it). And a failure to deal authentically with death might have something to do with an inability to deal authentically with life.

Mark Duffey started his ‘funeral concierge service’ in Houston after running a chain of funeral homes. In an article in The New York Times in July 2006, entitled ‘It’s My Funeral And I’ll Serve Ice-Cream If I Want To,’ he said: ‘Baby boomers are all about being in control… This generation wants to control everything, from the food to the words to the order of the service. And this is one area where consumers feel out of control.’ Duffey told the reporter, John Leland, that what people want are:

Services that reflect their lives and tastes. One family asked for a memorial service on the 18th green of their father’s favorite golf course, ‘because that’s where dad was instead of church on Sunday mornings, so why are we going to church? … Line up his buddies, and hit balls.’ Another wanted his friends to ride Harleys down his favorite road, scattering his ashes.

The biggest change, Mr Duffey said, is that as more families choose cremation — close to 70 per cent in some parts of the West — services have become less sombre because there is not a dead body present. ‘The body’s a downer, especially for boomers,’ Mr Duffey said. ‘If the body doesn’t have to be there, it frees us up to do what we want. They may want to have it in a country club or bar or their favorite restaurant. That’s where consumers want to go.’

This, of course, is exactly what the British gadfly and writer Jessica Mitford envisioned when she wrote The American Way of Death (1963) — a funeral without the ‘downers’ — notably a corpse and a creedal obligation.

In some areas of the US —– notably, the east and west coasts — the dismissal of the dead from their own ‘memorial services’ has become the new normal. There might be no better testimony on the east-coast variation on this theme than the recent memoir The Long Goodbye (2012) by the poet and critic Meghan O’Rourke.

A studious child who grew into a bookish woman, for whom reading and writing made sense of a world full of mystery and happenstance, O’Rourke writes with arresting power. ‘We read books on the porch all afternoon,’ she says in the memoir’s prologue, recounting the summers of her childhood. ‘I was a child of atheists, but I had an intuition of God. The days seemed created for our worship.’ The daughter of educators and a graduate of Yale, O’Rourke began her career, according to her website, as ‘one of the youngest editors in the history of The New Yorker’, and later at The Paris Review and Slate.com. Her first book of poems Halflife (2007) earned good reviews in the best of places.

So when her mother died, of metastatic colorectal cancer shortly before 3pm on Christmas Day 2008, little wonder that she would seek solace in books. Five pages of bibliography — from Philippe Ariès to Virginia Woolf — attest to her thoroughgoing scholarship. She avoids Mitch Albom, author of Tuesdays with Morrie (1997), the bestselling memoir about dying, but instead dives headlong into John Bowlby, the English psychoanalyst who did pioneering work on attachment; Erich Lindemann, the American psychiatrist specialising in bereavement; and Geoffrey Gorer, the English anthropologist who wrote an essay on ‘The Pornography of Death’ in 1955.

Likewise, little wonder that O’Rourke would be moved, after reading about death, to writing about it. The Long Goodbye and her most recent book of poems, Once (2011), are both memorials to her mother’s cancer and death, and the attendant griefs. Still, a death in the family is more than a readerly or a writerly event, and if O’Rourke’s mother had died at age 55 on the west coast of Ireland rather than the east coast of America, the obsequies would be entirely different.

‘Grief work’, as Geoffrey Gorer called it years ago, is not so much the brain’s to do as the body’s

The Long Goodbye, then, is a record of two bereavements. One is as old as the species, to wit: a child’s parent dies. The other, oddly postmodern, is special to the last couple of generations. The newer story, a fresh lament raised within the context of the old one, is the story of a culture and a family bereft of existential narratives and metaphors, gone ritually adrift and left clueless as to what to do when someone dies. As O’Rourke writes:

After my mother’s death, I felt the lack of rituals to shape and support my loss…. I found myself envying my Jewish friends the practice of saying Kaddish, with its ceremonious designation of time each day devoted to remembering the lost person. As I drifted through the hours, I wondered: What does it mean to grieve when we have so few rituals for observing and externalizing loss?

What O’Rourke missed was the year of mourning or some version of it, which customarily granted to the bereaved some time to grieve as well as outlining rituals meant to assist the mourner. She writes:

They took my mother’s body away so quickly. There we all were, touching her, hugging her, kissing her, saying goodbye. A year ago. For 20 minutes she was warm and she didn’t look dead… I could have spent days with the body, getting used to it, loving it, saying goodbye to it.

This inclination to ‘spend days with the body’, much like her ‘intuition of God’, are vestigial leanings towards the societal norms of wake and funeral, shiva and Kaddish — a primal obligation to witness or participate in the body’s burial or burning or disposition. These are customs that have been abandoned only in the past 50 years in favour of a more ‘virtual’ or ‘convenient’ commemorative event.

How far removed from any obligation to take part in the disposition of the dead is measured by O’Rourke without irony. It simply never occurs to her to wonder what has become of the body that was taken from the home. But a phone call and a credit card are not all that’s required to affect the disappearance of what remains of the person around whom so much of the family’s attention had circled for months before her final breath was taken. That it might never have occurred to the author to wonder about any of the adverbials — place, time, manner, cause, circumstance, degree — attached to the removal of her mother’s corpse, and that her obliviousness could survive a year is breathtaking for its detachment. She writes:

As I passed my father’s open bedroom door, I saw a large, square white cardboard container on a side table. My heart started beating faster, I went in. The box bore a plain label that read, in neat type, BARBARA JEAN KELLY O’ROURKE. If the box had always been there, I had managed never to see it. Now, the morning of the anniversary of her death, I recognized it as the container of my mother’s ashes.

Had her mother died on the West Clare peninsula on the other side of the Atlantic, her daughter and her family would have had to mix their grief with dozens of duties and details to do with her final disposition. They would have to help to lay her out, most likely in the bed in which she had died. They might assist with the washing, dressing and arrangement of the corpse — fresh linens for the bed, a rosary to hold her hands together, candles lit against any early putrefaction.

With no practical obligations to deal with around her mother’s dead body, O’Rourke has spent the intervening year searching out metaphors and resources and do-it-yourself ceremonials — the ubiquitous ‘celebration of life’. No longer attached to any ethnic, religious or regional culture that could be counted on for direction around a death in the family, she is left to reinvent the wheel that works the space between the living and the dead herself. She reads, she writes, she weeps, she tries to cope. Eventually, there’s a reading of John Keats and a selection of wines at a service where the good laugh is approved while the good cry seems awkward. She writes:

At the time the speedy removal felt natural, perhaps because I had no idea what to expect. Now, however, there is a blankness at the center of it that troubles me. We’re too squeamish for the ritualistic act of cleansing and purifying, the washing of the body, that used to take place in other times, and still does, in other places, but I wonder if it might have helped me to take care one last time of the body I’d cared about my entire life.

‘Grief work’, as Geoffrey Gorer called it years ago, is not so much the brain’s to do as the body’s. And it is better done by large muscles than by gray matter; less the burden of cerebral synapse and more of shoulders, shared embraces, sore hearts.

For the west-coast iteration of these issues there is, perhaps, no more reliable witness than Alan Ball, the creator and producer of the HBO black-comedy-drama television series Six Feet Under (2001-5). It followed the lives and times of the Fisher family who operate their own Ma and Pa mortuary in Los Angeles. Nathaniel Fisher, husband to Ruth and paterfamilias, is killed in the first episode of the show. It is Christmas Eve when the new hearse he is driving to the airport to pick up his son Nate is broadsided by a bus. His children, the prodigal Nate and the dutiful David (who has followed his father into the family business) and Claire, his wayward teenage daughter, must assist their mother with the funeral plans. This sets a pattern for the weekly series, each installment of which will begin with a death. What is clear is that the show needs a corpse in every episode for the plot to accomplish its purposes, the denouement of which very often coincides with the disposition of the body.

When I heard Alan Ball being interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, soon after the show’s premier in June 2001, I was flattered to hear him tell her that he had read my books on the subject of funerals and death. There were so many similarities. Like David Fisher, I had taken up my father’s business and, like David, I had embalmed my father when he died and, like David, I still heard my dead father’s counsel in difficult situations.

So I was a little starstruck, what with the Hollywood of it all, that an Oscar-winning artist and filmmaker had trained his attention on the quotidian work of morticians and their extended families. I also knew that what informed his vision were the experiences of death and grief in his own life, notably the horrific death of his older sister, on her 22nd birthday, when he was 13 and she was driving him to his music lesson, when the car was broadsided on the driver’s side.

During that Fresh Air interview, Gross had questioned Ball in some detail about his sister’s death and funeral. It was, by his own account, a life-changing event. ‘My life was very clearly separated into before and after at that moment,’ he said. ‘It was profoundly shocking… and I will carry deep scars until the day I die.’ He said he remembers the blood and the ambulance and the lie he was told by everyone about his sister being OK until the family physician, who was driving him home and saying he’d ‘have to be strong’ for his parents, let slip what actually happened.

When Gross asked him about her funeral, Ball said it was ‘surreal… very surreal’. He described it as the ‘traditional open-casket thing’ and, at his first sight of his sister in the casket, he said he wondered ‘Who’s that?’ They had given her ‘big boofy hair’ and a lipstick colour she would never have worn. ‘And I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘when they lay those bodies out in caskets, they look phoney, like wax figures’. He told Gross that for him this surreal event was ‘not at all comforting’.

In 1963, when Mitford’s exposé of the funeral industry came out, I was 15, working nights and weekends at my father’s funeral home

Worse still was that his mother’s grief, her loud weeping, her ‘breaking down’, was seen by the funeral home staff as problematic, and she was ushered into a side room behind a curtain where she might be expected to compose herself, as if amplified emotions were somehow inappropriate at the sight of your dead daughter’s body in a box. As if ‘breaking down’ was caused by some weakness or structural difficulty. Witnessing these reactions, along with the family doctor’s well-intentioned but mistaken counsel about ‘being strong’ for his parents, left the 13-year-old Ball no option for the authentic expression of his own deep hurt. The message he took from it was that grief should be quiet and private, muffled and subdued, hidden behind a curtain in an adjacent room. ‘That’s a lie!’ he told Gross in the interview. ‘What you need to do is scream, bang on the wall, tear at your hair, because grief is a primal thing and the only way out of it is through it.’ He described his family’s long-term reaction: ‘Everyone splintered and went into their own little world, and there’s a dynamic of that in the Fishers.’ By his own account, it took him another 25 years before he really dealt with his sister’s death.

From the very first episode of the first season of Six Feet Under it was clear that Ball wanted to change the conversation about funerals — a conversation that had, since the publication of Mitford’s The American Way of Death in 1963 and its revision and reissue in 1998, revolved almost entirely around how much a funeral might cost. Such a dialogue, after a while, becomes tiresome — How much did you spend? How much did you save? — as if the math of caskets mattered most.

That said, Mitford changed my life. In 1963, when her exposé of the funeral industry came out, I was 15, working nights and weekends at my father’s funeral home, greeting mourners at the door, and moving flowers and caskets. My father bought her book and said I should read it. At first, it seemed about funereal fashion — the boxes and cosmetics, the unctuous euphemisms of undertakers, their ‘beautiful memory pictures’ and ‘grief therapy’, the laughable sales pitches of cemetery moguls. Mitford took them all to task. In a culture that did not discuss these things, her willingness to do so was new. To an enterprise shrouded in darkness she brought her curiosity, wry humor and wary indignation. So much of what we do now when someone dies has been shaped by her commentary.

Whether or not they’ve ever read it, most of the families I’ve dealt through the years have in their heads a version of Mitford’s book. It has entered the conventional wisdom, seamlessly. That funeral directors are determined to sell you something you don’t want for a price you can’t afford, by preying upon your grief and guilt — these are all articles of that conventional wisdom. Not only was this at odds with my experience and perceptions of my father’s conduct, but they were at odds with a business model that relied on a community’s goodwill as a guarantee of future business. Because most of the families who called us for help were those who had called us years before in similar circumstances, it made no sense that we could retain their confidence by abusing the trust they had placed in us. Serving a family in accordance with their wants, needs, and financial abilities was not only good ethical conduct, but good business as well. And yet Mitford’s book has sold millions of copies since publication. My interest in her work and her impact on ours was keen and longstanding.

There was a fundamental element of funerals that Mitford truly abhorred. For all her carping about boxes and embalming, it was the bodies of the dead that bothered her, those unwelcome realities whose stillness leaves us dumbstruck and bereft of punchlines. It is largely on her advice that we have become, in the decades since she wrote her book, the first of our species to have our dead ‘disappeared’, ‘banished’ and ‘erased’. What put her off most about the American way of death was our tendency to mark our losses and grieve for our dead in ways that — for intensely personal reasons, as it turns out — she could never understand.

I’ve waited with the families of abducted children, foreign missionaries, tornado victims, drowned toddlers, and Peace Corps volunteers

Regardless of Mitford’s motivations, funeral directors unfailingly present an easy target for lampoon and ridicule. They are all too often their own worst enemies. Which is one of the reasons why Mitford’s book sold briskly in that first summer after publication and why things began to change in the mortuary marketplace. Almost immediately, there was an increase in the cremation rate, which had been below five per cent before Mitford’s book and has increased to nearly 50 per cent in the decades since. Whereas in England, cremation is now the norm and the living can accompany their dead to the crematorium, in North America where the tendency is to separate the disposition of the body from commemorative rituals, the cremation is accomplished often out-of-sight, off-site, with convenience, cost containment, and industrial efficiency, while the living gather later and elsewhere for their own purposes.

Here is where Alan Ball and Jessica Mitford differ. Mitford made much of caskets — how much they cost, how profitable they were, how devious or obsequious the sales pitch was. She disliked the boxes for their expense. But she especially disliked the bodies in the boxes for the untidy and unpredictable feelings they could be counted on to trigger. And while she wrote, often hilariously, about the foibles of morticians, she never wrote about the emotions she feared, about which her life had provided a substantial tuition — her first husband, first daughter, and first son all died tragically young. She recommended getting rid of both caskets and corpses, and letting convenience and cost-efficiency replace what she regarded as pricey and barbaric display.

Like Mitford, Ball sends up the smarminess and scams of those who see a death in the family as primarily a sales opportunity or an altar call, and like Mitford, he abhors the wax figurines of overly ‘prepared’ corpses. But whereas Mitford’s solution is to have the bodies and all costly accoutrements banished, Ball unambiguously wants the body back, undisguised, its mortal nature manifest, and the living welcome to their emotions, however raw; he wants to deal with the sad facts in the flesh. He rejects the virtual in favor of the real. He rejects ease and convenience in favor of the actual. He affirms the essential obligations of the funeral while dispatching the ridiculous accessories with grim drama and good humor.

Nowhere is the essential role that the deceased’s body plays in our responses to death felt more keenly than in those circumstances where bodies are lost or destroyed. Such was the case with the victims of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The terrible facts became all too clear as rescue and recovery teams worked through the rubble: that we would not get them back to let them go again. We would not be granted the little mercy to wake and weep over them. If humans are the ones who consign their dead to oblivions of our own choosing — the grave, or flames, or tomb, or sea, or open air — and if doing these things is one way we deal with death (because these hard duties have their comforts), then the further heartbreak and horror of those deaths that day is that it would not be kin that scattered them, or friends who carried them, or family ground that covered them, or their beloved who last whispered soft goodbyes. They were lost — too vastly buried, too furiously burned, too utterly commingled with the horror that killed them to get them back, to let them go again.

Like funeral directors and clergy everywhere, I’ve waited with the families of abducted children, foreign missionaries, tornado victims, drowned toddlers, Peace Corps volunteers, firefighters overcome by flames, passengers in fallen planes, casualties of wars — waiting for their dead to be found and counted, identified and returned to them from whatever damage or disaster claimed them. I have witnessed the odd relief, elation and thanksgiving at hearing that the lost are found and will be returned. I’ve stood with parents of children killed in crashes and other mayhems, viewing a body that cannot be restored to anything approximating its former appearance. And I’ve heard them give thanks for the recognisable limbs that have not gone missing, for the wounds that, however awful, did not dismember or decapitate even when they did disfigure. To have something, anything, unmistakably theirs to take leave of, say goodbye to, promise to remember — these are mercies in what often seem the most merciless of circumstances.

Likewise, I’ve heard no few well-meaning ignoramuses suggest that the body in the box, there among the gladioli and hushed respects, was ‘just a shell’ or ‘only the tent’ or some other metaphor to minimise the loss. They mean, of course, to say that they believe our souls outlive us, that we are more than blood and bone and corporality. But to say that there is ‘something more’, albeit unseen, is not to say that what we do see is ‘something less’. The bodies of the dead are not ‘just’ anything or ‘only’ anything else. They are precious to the living who have lost them. They are the seeing — hard as it is — that is believing, the certainty against which our senses rail and to which our senses cling. They are the singular, particular sadness that must be subtracted from the endless mundane tally of sadnesses that are the everyday history of the world.

Whatever our responses to death might be — intellectual, philosophical, religious, ritual, social, emotional, cultural, artistic, etc — they are firstly and undeniably connected to the embodied remnant of the person who was. And while the dead can be pictured and imagined and conjured by symbol and metaphor, photo and recording, our allegiance and our primary obligations ought to be to the real rather than to the virtual dead.

Thus, on my short list of the essential elements of the good funeral, the presence of the dead is the first and definitive element. Memorial services, celebrations of life, or variations on these commemorative events – whether held sooner or later or at intervals or anniversaries, in a variety of locales – while useful socially for commemorating the dead and paying tribute to their memories, lack an essential manifest and function: the disposition of the dead. The option to dispose of the dead privately, through the agency of hirelings, however professional they might be, and however moving the memorial that follows, is an abdication of an essential undertaking and fundamental humanity.

A second essential, definitive element of a funeral is that there must be those to whom the death matters. A death happens to both the one who dies and to those who survive the death and are affected by it. If no one cares, if there is no one to mark the change that has happened, if there is no one to name and claim the loss and the memory of the dead, then the dead assume the status of Bishop Berkeley’s tree falling noiselessly in the forest: if no one hears it, it did not fall, it never was. It is the same with humans.

A third essential, definitive element of a funeral is that there must be some narrative, some effort towards an answer, however provisional, of those signature human questions about what death means for both the one who has died and those to whom it matters. Thus, an effort to broker some peace between the corpse and the mourners by describing the changed reality that death occasions is part of the essential response to mortality. Very often this is a religious narrative. Often it is written in a book, the text of which is widely read. Or it might be philosophical, artistic, intellectual — a poem in place of a psalm, a song in place of prayer — either way, there must be some case to be made for what has happened to the dead and what the living might expect because of it.

A fourth and final essential, definitive element of a funeral is that it must accomplish the disposition of the dead. They are not welcome, we know intuitively, to remain among us in the way they were while living. Furthermore, it is by getting the dead where they need to go that the living get where they need to be. And while this disposition often involves the larger muscles and real work, it also enacts our essential narratives, assists in the process of our essential emotions, images and intellection about the dead, and fixes their changed status in the landscape of our future and daily lives, whether the dead are buried, burned, entombed, enshrined or scattered, hoist into the air, cast into the sea, or left out for the scavenging birds, our choice of their oblivion makes their disposition palatable, acceptable, maybe even holy, and our participation in it remedial, honorable, maybe even holy.

These are the four essential and definitive elements that make a human funeral what it is. Once we can separate the essential elements from the accessories, the fundamental obligations from fashionable options, the substance from the stuff, the necessary from the knick-knacks, the core from the pulp, we might be able to assign relative measures of worth to what we do when one of our own kind dies. We might be able to figure not only the costs but the values. Thus, coffin and casket, chrysanthemums and carnations, candles and pall, vaults and monuments, limousines and video tributes — all of them accessories, non-essentials. They might be a comfort but they are non-essential. Same for funeral directors and rabbis, sextons and pastors, priests and clerks, florists and lawyers and hearse drivers — all of them accessories who can, nonetheless, assist the essential purpose of a funeral. And when we do, when we endeavor to serve the living by caring for the dead, we are assisting in the essential, definitive work of the funeral and the species that devised this deeply human response to death.

This is an extract from The Good Funeral by Thomas G Long and Thomas Lynch. Available autumn 2013 from The Thoughtful Christian. Used by permission of Westminster John Knox Press. All rights reserved.