For as far back as I can remember, I have been preoccupied with what it will be like to die. As a girl, I would often zone out on my bed, or at my desk in school, imagining that I was on the verge of death, and trying on a range of possible reactions: terror, confusion, grief. What I really hoped for in those moments of morbid fantasy was a kind of peaceful, alert confidence. I would be brave and mature enough when I died. I would let go and master whatever might be waiting on the other side. But, mostly, all I could authentically muster was a shiver of panic.

As I moved into adulthood, I began to collect glimpses into the deaths of family members and friends. There were hints at how to be at peace, but some of these deaths were sad and torturous. An elderly friend with pneumonia who expired tethered to ICU machines against her wishes, another who succumbed to cancer, leaving two young daughters behind, and another who died of AIDS, shunned by his family, delirious and heartbroken. Living in a society that offers few lessons on how life should end, and where the moribund are mostly hidden from view, it’s hard to find tangible examples of dying well.

A few years ago, I signed up to volunteer with a New York City hospice. I was inspired by a dying friend who described how lonely she was being terminally ill in a death-phobic culture. Maybe I could be of comfort to someone like her. But also, I simply wanted to be near dying people – to get an education in death, to glean some coordinates for the roadmap to my own end.

My tenure as a volunteer began with a six-week training programme, a valiant effort by the volunteer coordinators to prepare us – for the iron grip of medical bureaucracy, paperwork and protocols we would have to endure, as much as for visiting with the dying and their families. The first day, 35 of us sat around a conference table and engaged in a hospice kind of icebreaker, in which we each had to narrate what we wanted our own deaths to be like.

One woman imagined a lovely death arriving as she dozed in a rocking chair on the porch of her childhood home in South Carolina, surrounded by kin. A graduate student described his perfect end in the midst of some exhilarating adventure – skydiving or hiking in the Andes: a sudden accident in the midst of thrill; no lingering pain. A retired nurse with grown children envisioned a serene, solitary demise in her bed, at home in Brooklyn, lulled by the familiar whir and soft wind emanating from the ceiling fan.

Only a handful of us mentioned a death inspired by religious ethos – getting right with God, say, or moving toward a state of enlightenment. I attributed this partly to the fact that we were in the centre of a secular metropolis – had we gathered, say, in Kansas, the group’s orientation very likely would have skewed deeply Christian. But part of it was due to the fact that none of us was actually dying. Reams of deathbed chronicles report that when death is imminent, many people, even confirmed atheists, reach down to long-buried religious roots for solace and direction.

No one wanted heroic medical treatment to prolong life if death were imminent or if we were suffering terribly. In essence, we described our desire for control over the circumstances of our deaths, and for the ability to tailor them to our personal preferences, and in so doing we were in tune with our culture. According to sociologist Tony Walter, ‘the good death is now the death that we choose’. It is shaped, he writes in The Revival of Death (1994), ‘not by the dogmas of religion nor the institutional routines of medicine but by the dying, dead or bereaved individuals themselves’.

Indeed, the more deaths you’re exposed to, the more diversity of experience you see. Scores of studies by social scientists and articles by death experts, many based on interviews with dying people and their caregivers, point to the vast range of good death concepts and experiences. ‘I can’t presume to know what anyone else’s good death looks like,’ says Barbara Coombs Lee, an intensive care nurse-turned-lawyer who co-authored Oregon’s Death with Dignity law in 1994. ‘A good death is one that comports with the way we’ve lived our lives, with our manifest values and beliefs. And that is going to differ for everyone.’

My hospice group might not have been a scientifically selected sample, but we formed a robust cross-section of urbanites who wanted to approach death conscientiously and with purpose. In placing so much emphasis on control and self-determination, and faith in the idea that choice would remain within our grasp, were we ignoring the fact that dying is the ultimate loss of control?

Until relatively recently, Western people’s expectations about death had little do with personal choice. Cultural prescriptions for how to die have been around for as long as people have organised themselves into societies, and for the most part, they were rooted in belief about how things would go in the afterlife. For the ancient Greeks, the goal was euthanasia, referring, literally, to the ‘good’ or ‘noble’ death, as of a hero in battle or an upstanding citizen departing this world with absolute moral purity – the better to face the trials that awaited in the underworld. The transcendent value of pleasure in the Graeco-Roman world figured into the good death, too. A second-century astrologer noted that a person born under a particularly propitious constellation would ‘die well falling asleep from food, satiety, wine, intercourse or apoplexy’.

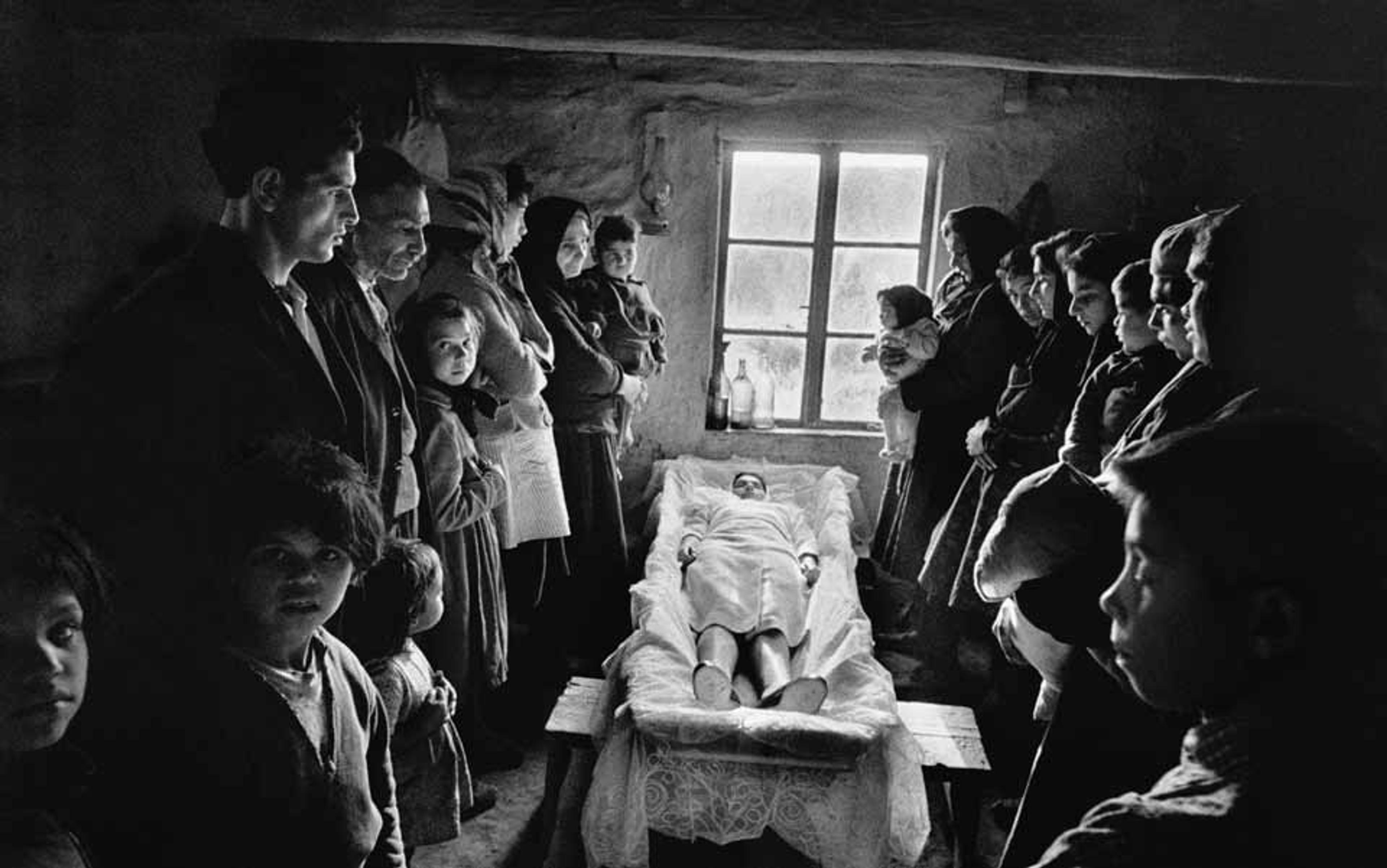

By the 15th century in western Europe, how-to guides known as Ars Moriendi (‘The Art of Dying’) provided Christians with very specific deathbed rules of conduct. These manuals reached their apotheosis with a bestselling booklet by the English cleric Jeremy Taylor called The Rule and Exercise of Holy Dying (1651), which, thanks to the advent of vernacular printing, proliferated for the next 200 years. Taylor’s tome and others like it instructed dying people on ‘how to give up one’s sould gladlye and willfully’, how to resist the devil’s temptations at the time of death, how to emulate Christ and what prayers to recite. A priest was to interrogate the dying person about the state of his soul and plans for the afterlife, and the many onlookers were to learn what they could, both about the spiritual condition of the deceased and how to behave when their own time came.

medical intervention to prolong lives in hospitals reached such a pitch that last words could hardly be uttered

These aspects of the good death dominated in the Judeo-Christian world well into the 19th century. Family had always figured prominently in the ars moriendi – to assemble around the bed, perform rituals, encourage the dying person, and imbibe his momentous last words. During the American Civil War, when a tenth of the US population was perishing, away from home, ‘soldiers, chaplains, military nurses, and doctors conspired to provide the dying man and his family with as many elements of the conventional Good Death as possible’, writes the historian Drew Gilpin Faust in This Republic of Suffering (2008), her masterful study of death in that conflict. They struggled ‘even in the chaos of war to make it possible for men – and their loved ones – to believe they had died well’. The use of embalming and undertakers – professional death attendants – became widespread, as returning the body to the family, whenever possible, was imperative to the closure of good death.

In some ways, the cultural phenomena surrounding death that emerged during the crisis of war became routine with the more or less permanent upheavals of the industrial revolution. Like soldiers mobilised for battle, huge swaths of the population began moving away from home, rupturing the family and community structures that once oversaw the dying process. The rise of the commercial funeral industry was part of a trend that legislated – and priced – home dying virtually out of existence. Longer life expectancy, combined with life-preserving medical technology, meant that more and more people would eventually die with dementia or bodies that had in other ways outlived their faculties. By the middle of the 20th century, medicalised death was the norm. As Katy Butler describes it in Knocking on Heaven’s Door (2013), a memoir of her parents’ deaths, medical intervention to prolong lives in hospitals reached such a pitch that last words could hardly be uttered – dying people’s mouths were too clogged with tubes and respirators to speak.

The modern hospice and palliative care movements emerged in compassionate reaction to the pain, loneliness and grief in which so many medicalised deaths end. Set in motion by Dame Cicely Saunders, an Anglican nurse and physician who founded the first modern hospice in 1967 in London, and the psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, whose work with the terminally ill inspired her ‘five stages of grief’ paradigm, these models focus on the psycho-social needs of the dying person and the alleviation of physical symptoms. A good death, from the view of a hospice, includes ‘an open awareness of dying, good or open communication, a gradual acceptance of death, and a settling of both practical and interpersonal business’, writes Beverley McNamara, an Australian sociologist who studies the concept of good death in hospitals and nursing homes. ‘In order for the social and psychological aspects of death awareness and acceptance to take place,’ she adds, ‘the dying person’s suffering should be reduced and they must be relieved of pain.’ Spiritual concerns, too, are taken into account as part of the psychological package, but are not necessarily given more weight than other dimensions of care.

This version of how to die – a sort of hospice ars moriendi – has become the conventional wisdom about what comprises good death among many of the people who study modern dying, or work in the trenches of end-of-life care. I think back to my volunteer training group and the salient themes that recurred in our disparate fantasies. We wanted a minimum of pain and discomfort, a favourite place (usually home), privacy and a congenial ambience (skydiving notwithstanding), our worldly affairs in order, the chance to say goodbye and sew up loose emotional ends with loved ones. A peaceful and, ideally, lucid mind.

I wanted all those things too, but the notion that I could guarantee myself any of the external trappings of a good death – comfort, loving bystanders, freedom from pain, a ceiling fan – has always struck me as tenuous. As a teenager wound up in thoughts of mortality, I first found an inkling of relief when I began to meditate, inspired by some instructions I read in a yellowing, 1960s paperback about yoga for weight loss. Those early attempts at quieting the relentless chatter in my mind and feeling the thread of my breath were a revelation – there was something I could access inside that seemed reliable, and softened my worries about dying. I sought out more books on meditation, began to visit a local Zen centre, and in the intervening decades, adopted Theravada Buddhism as my religion.

That same sort of yearning for inner peace has led several generations of Westerners to pick up an Eastern compass. In the 1960s and ’70s, as Saunders and Kübler-Ross were railing against the heartless treatment of the dying, and forging new models of care, seekers began filling the spiritual vacuum at home with yoga, Buddhist meditation and such guideposts as the Tibetan Book of the Dead, all of which uphold death as part of a cyclical journey requiring rigorous preparation – not as an awful terminus.

The first Buddhist I knew to die was the poet Allen Ginsberg. He was surrounded by friends, students and his teacher, all chanting and sitting vigil in his East Village apartment, before, during and for three days following his death, according to Tibetan Buddhist custom. It was understood that the people around him could actively assist his passage, and that the final moment of consciousness was paramount, the most important moment of his life.

On my very first outing as a volunteer, I experienced a hospice death. I shall call the patient I was assigned to visit Sonia, a 51-year-old grandmother with nine grown children and many grandkids. She had struggled with a decades-long crack cocaine habit, and was now consumed by breast cancer she had mostly neglected to treat. At the close of an afflicted, sometimes homeless life, Sonia had summoned her waning energies to ask whichever family members visited for forgiveness, to say she loved them, as she was doing with a daughter-in-law when I walked in. Her translucent lips curved into a weak smile when I placed a tiny flowering plant on the table near her bed and then she sank into a deep, interior quiet, absorbed, it seemed, in the work of shutting down.

More than 70 per cent of people in the US say they want to die at home, but more than 80 per cent end up dying in hospitals and nursing homes

I was asked to call the hospice hotline, to fetch a chaplain to give Sonia her last rites – the nurses and her daughter-in-law thought it was time. Staff bustled in and out, checking the morphine drip that kept her pain at bay, and glancing at the empty urine bag (Sonia had stopped eating and drinking several days before). Her face was smooth and pale as parchment, her skin refrigerator cool, and her breaths came in short, jagged sips, punctuating wide gullies of profound silence.

For several hours I sat, my hand on her arm, in a state of electrified attention, watching a stranger disengage from life. Sonia released her last breath, almost imperceptibly, in the characterless, air-conditioned room of the run-down Brooklyn nursing home. ‘She had a good death,’ a hospice social worker told me over the phone the next day, when I described my time with Sonia. ‘A good death is good for everyone.’ As I left the nursing home and walked out into the stunning heat of the July day, I was struck by the contrast between the acute mystery of dying, and the banal settings and circumstances in which it usually takes place. As my physician friend Liz said to me once, from a clinical standpoint, a good death is usually anticlimactic. ‘Whatever is happening for the person internally, spiritually, you’re not going to see,’ she said. ‘But when a death is going badly, you know it.’

Still, in a world as heterogeneous as ours, can there be one ars moriendi that fits all? Can we safeguard the common denominators of good care and still accommodate wide-ranging individual choice? Ironically, hospices and palliative care teams – entities that grew out of a deep desire to mitigate the suffering of dying people – have come under fire for being too rigid and unimaginative in their views and rhetoric. Just because someone is dying in hospice care doesn’t mean they want to talk about it. Nor should be expected to articulate how they might hope their deaths to be.

Some argue that the Western psychological approach to good death leaves out the myriad social, ethnic and religious currents that make up our global civilisation. The anthropologist James Green, whose book Beyond the Good Death (2008) has become a primer for the burgeoning number of college courses on death and dying, has no use for Kübler-Ross’s stages, which he sees as far too narrow and culture-bound. Since retiring from academia, Green has worked as a hospital chaplain in Seattle, a vocation he says has proved to him that ‘a white, middle-class model for dying is not a universal model. Not everyone is looking for some happy contentment and growth. The ending of suffering may not be what they’re looking for.’

Certainly, there are plenty of faith traditions in which enduring suffering is seen as an indispensible part of dying, a source of honour and the key to salvation. Take the poet and undertaker Thomas Lynch whose mother, a devout Catholic, was determined to emulate the passion of Christ as she died. ‘She refused the morphine and remained lucid and visionary’, offering her pain ‘up to the suffering souls’, writes Lynch in The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade (1997). ‘I’m not certain it works – only certain that it worked for her.’

Other people, for whom a room full of hovering caregivers or worried relatives would be the antithesis of a good death, might prefer to die alone, undistracted by the pull of the living. At the time I began writing this essay, my 83-year-old uncle died, after breaking two ribs and then contracting the flu in hospital. He had fallen and lain on the floor of his apartment for two days, likely in considerable pain, before anyone found him. It sounded bad, but he had decided he was ready to go, and this was his opportunity for exiting, on his terms. The truth of that was borne out by the affection and goodwill he showed his family at the end, and which infused his joyful memorial service.

Nowhere is the issue of choice in constructing a good death more fraught than in the discourse around the ‘aid in dying’ movement and the passage of laws, such as one ratified in Oregon in 1997, or another recently debated in the British House of Lords, that allow doctors to prescribe a lethal dose of medicine to a terminally ill person who wants to hasten her own death. Remarkably, less than half of dying people who obtain lethal drugs end up using them. ‘That’s the palliative effect of choice,’ says Coombs Lee. ‘People experience improved quality of life when they have the means to avoid their worst nightmare.’

Needless to say, it’s extremely hard to maintain control, autonomy and independence when we’re approaching the end. The one strategy for getting to a good death that everyone seems to agree on is advance planning – planning now – while we are still alive and cogent. ‘One should be ever booted, spurred and ready to depart,’ wrote Michel de Montaigne in the 16th century. In arranging temporal things – making wills, assigning health proxies, researching and sharing our wishes for end-of-life care and for the preparation and disposition of our own bodies – we can hedge our bets for dying as we want and avoid burdening our caretakers with heavy, confusing decisions when we can no longer make them. More than 70 per cent of people in the US, for instance, say they want to die at home, but more than 80 per cent end up dying in hospitals and nursing homes, in part because no advance directive made those wishes known.

Apprehending the truth that all things arise and pass away might be the ultimate groundwork for dying

Putting our worldly affairs in order can also make it easier to drop the attachments and anxiety that muddle the mind as we approach death. But even the best-laid plans can be torn asunder, or overlooked. Death is unpredictable and prone to disruptions, even when papers are in order, or when a hospice has been brought in. There can be unwanted medical interventions, misunderstood directions. We might be too demented or impaired to know what’s happening. We might die suddenly – violently – hit by a car or in cardiac arrest, without what the psychologist Ronna Kabatznick calls, in reference to post-tsunami Thailand, ‘the privilege of transition’ – a deathbed, a chance to say goodbye, a body to mourn over.

If my experience with hospice care has taught me anything, it’s that the only way to ensure some measure of wellbeing at death, given all that can go awry in the time leading up to it, is through developing an inner strength that cannot be shaken by the demise of the body, by the loss of all that is dear to me, or even by pain. Looking back on my enduring childhood obsession with dying well, it’s no surprise that I would jibe with this view. Buddhism teaches that we can attain a reliable, deathless happiness through the cultivation of discernment, ethics and meditative concentration. Apprehending the unavoidable truth of impermanence – that we are of the nature to get sick, grow old and die, that all things arise and pass away – might be the ultimate groundwork for dying.

Over the course of several years, I sat with dementia patients receiving hospice care at a down-at-heel nursing home in Manhattan. Few of the dying people I met there seemed to have family or friends who visited regularly, and for the most part, it was impossible to know their plans for death, or if they’d had any. Most seemed lonely and anxious. A man in his seventies, whom I shall call Mr Pollard, appeared to be on a brutal psychic treadmill, reawakening, moment after moment, into panic, not knowing where he was or how he’d gotten there. He would relax a little when I held his hand.

Of course, improving the circumstances and care of the sick, old and dying – doing what we can to ensure people get the good death they want – is critical; a humanitarian revolution that has yet to take place. But most of the circumstances of our deaths are ultimately beyond our control. Any one of us could be Mr Pollard. It could be me sitting in a drenched diaper with the TV blasting. It could be me having food shovelled in my mouth when I don’t want to eat. It could be me asking for morphine when I’m wracked with pain and hearing I’ll have to wait two hours for the next dose. The only thing that is within our control is inside. To die contentedly like that, in a dingy room with no privacy, filled with indifferent strangers, will take serious inner work. If I can get that ‘thing’ from the meditation, it will be the most reliable medicine I can have, accessible whenever I need it, when all else fails. As I see it, it’s the only hope for the good death I want – unburdened, unafraid, mindful.