Antibiotics, defibrillators, feeding tubes and ventilators are lifesaving tools that sometimes become weapons to prolong life against our will. None of us can escape death but some of us want to shape our final time on earth. We don’t want to live for years in a nursing home rendered unconscious by late-stage dementia; or brain-damaged by strokes; or on and off ventilators with recurring pneumonia, growing so frail we lose the choice of an unfettered death at home. We grow determined in our wishes. We formalise end-of-life plans asking for comfort care only, no heroic, invasive or futile medical procedures, no artificial food or hydration, minimal feeding. We assemble and legalise these plans. We calm our fears.

It sounds rational and safe. But in reality, the faith we place in legalised directives, or in the medical professionals charged with enforcing them, has proven unwise. Medical professionals ignore such directives, no matter how carefully we’ve crafted them, particularly if we end up in a hospital or nursing facility.

I’m not talking about assisted suicide. I’m talking about plans that specify withholding treatment, such as a ventilator, a feeding tube or antibiotics for pneumonia, for a person who won’t recover, prolonging death even over fierce objections from family members. This situation results, in part, because directives go against the culture of medicine, which focuses on healing, on doing everything possible even if what’s possible proves futile. Our wishes might be viewed as disrespecting life, and medical personnel can prevent us from dying, no matter how airtight our legalised directives are.

The terms ‘advance directive’ and ‘living will’ are used interchangeably, but they’re actually not the same, even though the intent of each is to prevent futile medical treatment. Advance directive is the generalised term for the legal documents spelling out our end-of-life wishes, should we become unable to express them at the time. There are three types of advance directives: living wills, healthcare power of attorney, and healthcare proxy. Living wills detail the type of medical treatment people might not want, such as artificial nutrition, antibiotics, dialysis, resuscitation, and so on. Both healthcare proxies and powers of attorney appoint another person to make medical decisions on our behalf.

The issue is critical because the very nature of death has changed in modern times. By the 1960s, medical advances such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and portable defibrillators could restart hearts away from hospital settings. Artificial ventilation kept an unconscious person breathing, and feeding tubes kept them fed and hydrated. But restarting the heart sometimes meant people survived with brains so damaged they lived only by artificial means. This changed the legal definition of death from solely a cardiac event to include brain death, defined as irreversible loss of brain function, including the ability to breathe on one’s own. With this new definition, people on ventilators could be brain-dead, but have beating hearts and be warm to the touch. The shell of a person would be functioning, but everything we knew and loved about them would be gone.

In 1969, to protect the living and the brain-dead, the US attorney and human right advocate Luis Kutner, co-founder of Amnesty International, proposed the idea of living wills. These wills could protect people from futile end-of-life treatment, as long as medical professionals respected their wishes.

But very few young people had documents drawn up, and those who wanted loved ones off ventilators, feeding tubes or both had to petition the courts, and found pushback at every turn. The first such case came in 1976, in the US. Karen Ann Quinlan was 21 when she collapsed at home after attending a party where she mixed alcohol and tranquilisers. Afterwards, she needed an artificial respirator to breathe and a feeding tube to eat. After months with no improvement, Quinlan’s father, who’d been appointed guardian, asked her doctors to remove the respirator. They refused after a prosecutor warned they could face homicide charges. The Quinlans went to court, and eventually the New Jersey Supreme Court sided with them. The respirator was removed, but Quinlan remained in a coma until her death in 1985.

During media coverage of the Quinlan case, my mother and I had our first conversation about-end-of life issues. In 1976, she was 61, the same age I am now. We were both horrified by the effort and agony of Quinlan’s parents in their fight. My mother said that if she were in the same situation she ‘never wanted to be hooked up to machines’.

After Quinlan, each decade brought signature end-of-life cases in which young men and women who did not have living wills ended up on respirators or feeding tubes after a sudden illness or accident. In Missouri, where I live, the parents of Nancy Cruzan fought the Department of Health to have their daughter’s feeding tube removed. Cruzan had been thrown from her car during an accident in 1983 when she was 25. She was found, unconscious in a ditch of water, revived and placed on a feeding tube (a decision her father later said he regretted). In 1987, her parents requested removal of the tube, after their personal physician assured them that Cruzan would not suffer. The Department of Health refused saying that they ‘would not starve somebody to death’. The fight went to the Supreme Court; Cruzan’s family eventually prevailed and in 1990, Cruzan’s feeding tube was removed and she died. But protesters kept a vigil at the care facility. Some were so loud they had to be moved so the family could not hear them.

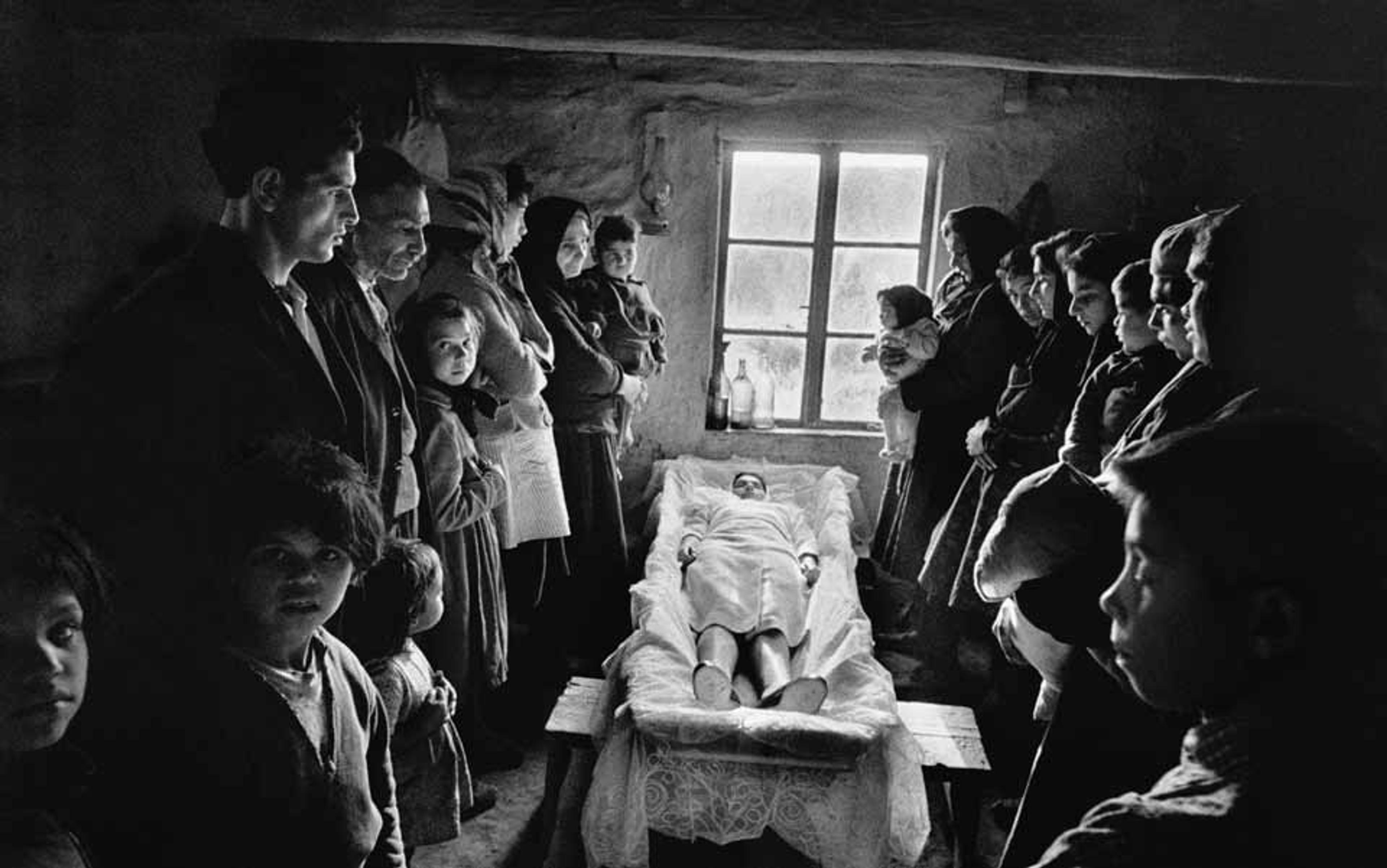

Removing food and hydration from a person with no hope of survival touches the core of our religious, political and cultural beliefs

The fight for the right to die became even more heated over the years. In 2009, the US Conference of Catholic bishops came out against removing feeding tubes from an unconscious person if that person was not imminently dying; they even wanted to keep feeding those with advanced-stage dementia, a terminal illness with only one outcome. In fact, the Church requires doctors to ignore advance directives that conflict with Church doctrine, and insists that food and hydration, even artificially administered, do not constitute medical treatment. These policies emanating from Rome matter to the secular world because the Church owns and runs hospitals throughout the US. In some cities, for example Durango in Colorado, people have little choice about which hospital to use because the Catholic Church owns and runs the only general hospital in the area. If a person with an advance directive seeks medical help in a Catholic-owned hospital, that directive may not be honoured.

The Catholic Church and other religious organisations have been echoed by political voices worldwide. Take the case of Terri Schiavo, in a persistent vegetative state since collapsing at her home in Florida after going into cardiac arrest in 1990, at age 27. In 1998, Schiavo’s husband petitioned the courts to have her feeding tube removed; her parents wanted the tube kept in place. In 2001, the tube was removed but, 60 hours later, a judge ordered feeding reinstated. In 2003, another judge ordered the feeding tube removed but a special session of the Florida legislature gave the then Governor Jeb Bush authority to keep it in place. In 2004, that ruling was deemed unconstitutional. Finally, after a US District Court intervened, Schiavo died on 31 March 2005. Her autopsy showed ‘massive, irreversible brain damage’.

The firestorm surrounding these cases captured the essence of the public debate. Removing food and hydration from a person with no hope of survival touches the core of our religious, political and cultural beliefs. For some, keeping loved ones alive by artificial nutrition means prolonging a death already underway. For others, removal of artificial food and hydration means starving a person to death.

The lingering effect of such public cases and debates was double-edged. While the uproar sparked interest in advance directives, it also provoked a backlash against them. ‘This really is the patient’s decision, but if the patient has dementia or can’t decide, then this should be the family’s decision,’ Mildred Solomon, president of the Hastings Center, a nonpartisan bioethics research institution in New York, told me.

In Germany, Australia and the UK, doctors who ignore end-of-life directives can be charged with assault

Still, after 40 years of advance directives, the religious right, the Catholic Church and many in the medical community seem unprepared to let people die. This is why I worry that my mother, now 99, might not be allowed to die when the time comes. I’m her primary caregiver, and she lives with my husband and me, although one of my sisters watches her for long stretches. Because my mother’s dementia has been worsening over the years, my sisters and I met with an attorney three years ago, updating her financial paperwork and giving me healthcare power of attorney.

Now, her wishes to avoid a prolonged death are my legal and ethical responsibility, but so many things could go wrong. Patients are often transferred between care facilities and directives get left behind. In the US, for instance, only a few states use electronic records that would alert the medical community to an advance directive.

My mother could die far from home. Or try to die. US laws differ from state to state, and end-of-life care varies from facility to facility. What seems most universal is the extent to which geography determines whether medical staff respect or ignore advance directives. In Japan, they are not widely accepted. Across Europe, the legal status of end-of-life wishes depends on the country: in Ireland, Portugal, Bulgaria and Italy, advance directives have no legal standing. In some European countries that legally recognise advance directives, such as the Netherlands and Spain, doctors can deviate from the plans for ‘good medical reasons’. In Germany, Australia and the UK, doctors who ignore end-of-life directives can be charged with assault.

Physicians worldwide give many reasons for pushing aside a patient’s legal wishes. Doctors tend to work in specialised silos, and might pressure family members to keep treatment going without taking into consideration how such care would burden the patient. The medical community is focused on curing people by trying everything, and can be reluctant to give up on treatment.

‘At best, doctors are afraid they will be sued for negligence if they don’t do everything medically possible. At worst, it’s money for paid intervention, and they will go on treating regardless of the patient’s overall condition,’ says Colleen Cartwright, director of the Aged Services Unit at Southern Cross University in Queensland, Australia. Even if treatment could prove futile, some physicians might be uncomfortable – or fearful they will be accused of euthanasia – if the directives don’t include very specific language, such as refusing dialysis if kidneys fail.

In 2012, Linda Ganzini of the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland (one of three states in the US where medical aid in dying is legal) and colleagues published results of a nationwide survey in the Journal of Palliative Medicine detailing how often palliative-care physicians are formally accused of murder and euthanasia. More than half said measures from withdrawal of food and hydration to palliative sedation were ‘characterised as euthanasia’. Four per cent said they were officially investigated for hastening a patient’s death even when that was not the intent.

Tia Powell, a bioethicist at the Montefiore Einstein Center for Bioethics in the Bronx, New York, uses the following scenario to explain how doctors can still honour directives that might not spell out everything. A frail, elderly man lives in a nursing home after a stroke. He can no longer communicate, and his nephews are the only family who speak for him. He ends up in hospital with complications from an infection, then kidney failure sets in. His advance directive specifies no ventilator and no resuscitation following cardiac arrest, but says nothing about dialysis. Yet his nephews feel certain he would not want that treatment and make it known to the kidney doctor, who’s pushing for dialysis. The nephews refuse and send their uncle back to the nursing home where he dies in peace. ‘No law says you have to try every treatment on somebody if they didn’t tell you not to,’ Powell explained.

In 2007, the US physician Henry Perkins wrote in the Annals of Internal Medicine that there are too many problems with advance directives for them to be useful, even when the directive is legally valid and precise. Perkins used this example. An elderly patient has frequent bouts of pneumonia that put him in hospital on ventilators, where his primary care physician suggests a formalised end-of-life plan. With their physician, the patient and his wife craft a directive that spells out treatments he would and would not want, including resuscitation or mechanical ventilation. The family’s doctor also has the foresight to ask who would likely be present in a medical crisis, and the couple mention their daughter, who would be apprised of her father’s wishes and given a copy of the directive.

Perkins’s example then illustrates how quickly an advance directive can unravel. Back home, the patient starts to have trouble breathing, his wife calls 911. An ambulance takes him to hospital. He has pneumonia again and is unresponsive. Their physician is out of town, but his wife has brought a copy of the directive and gives it to the hospital staff. Together they decide against antibiotics and choose to give only care that would make her husband comfortable. This is how advance directives can and should work.

But then the patient’s daughter arrives at the hospital, learns that her father is receiving comfort care only, and accuses her mother and the hospital staff of ‘murdering Daddy’, threatening lawsuits and to notify the press unless her father gets antibiotics and other forms of life support immediately. The daughter bullies her mother and the medical staff, and the patient receives antibiotics and life support. He dies anyway but Perkins emphasises that it’s a death the patient never wanted, and one he took time and care to avoid.

if care workers in a nursing home can’t accept death as part of life, then they probably should work elsewhere

This could happen so easily in my family. Faced with the same scenario, I too would choose against antibiotics but in my heart I know that one of my sisters could well be the daughter in Perkins’s example, even though my sisters sat in the attorney’s office when my mother named me as her healthcare proxy and neither of them objected. I could be faced with honouring my mother and destroying my relationship with my sister, who might find she cannot let my mother go.

What I am most worried about where my mother is concerned is that she will end up in a nursing home and the staff will interfere with end-of-life decisions. I have seen this happen before. In 1994, my mother-in-law was dying in a nursing home from complications of Alzheimer’s disease. For the first three days of her death watch, we kept her lips moist for comfort but didn’t force her to eat. Then a nurse, a former emergency medical technician, angrily marched in carrying a 50cc syringe of artificial nutrition, and announced he was going to feed her. He pushed the button to raise her bed with such force the ensuing motion jerked my mother-in-law’s comatose body. I thought my husband was going to faint. I ran to the nursing station and raised hell, and that nurse never returned. I remember thinking that if healthcare workers couldn’t recognise death as imminent or realise that dying people don’t eat, and if care workers in a nursing home can’t accept death as part of life, then they probably should work elsewhere.

In the 20 years since my mother-in-law died, end-of-life issues surrounding dementia have gone downhill, especially in terms of withholding food and hydration. A person might craft an advance directive – while mentally sound – that includes wishes to withhold food and water if dementia reaches end-stage. However, because dementia robs memory, that person will have forgotten the instructions and might willingly accept food. In such an instance, the medical staff could very well ignore the directive, forcing the family to court.

This type of situation is publicly unfolding in Canada right now. The family of Margaret Bentley, a former nurse, is fighting to implement her end-of-life wishes. She is in late-stage dementia and no longer speaks to, or recognises, them. Her living will states that she did not want ‘nourishment or liquids’ in such a circumstance. The nursing‑home staff feeds Bentley by spoon, and the family wants it stopped. In 2013, a judge sided with the nursing‑home staff. As of April 2014, the family is appealing.

Barbara Coombs Lee, president of the end-of-life advocacy organisation Compassion and Choices, told me it is a ‘common and valid way for someone to say ahead of time: “If I have forgotten how to eat and you have to force my mouth open and rub my throat, forget about it.”’ Lee explained that she has worked with people in the mid-stage of dementia who, during a lucid moment, realise they don’t want to go any further: they see themselves ‘at the edge of a crevasse they don’t want to go down’. These patients enlist family support, get into hospice care, and write themselves notes about stopping food, in case they forget, which removes the burden from the family. Dying bodies actually don’t want food or water. Dehydration triggers the release of endorphins, easing a peaceful death. Quite the reverse happens if a dying person is hydrated: nausea, vomiting and increased discomfort can result.

These days, I think a lot about what will happen when my mother dies. She’s been in the hospital twice in the past few months, riding the carousel from home to the emergency room to a nursing floor and back home again. At first, doctors suspected urinary tract infection but in the hospital her liver enzymes went up, which spurred an ultrasound and a CT scan; two months later she needed a procedure requiring light anaesthesia to ease a constriction in her throat and help her swallow. She’s still healthy and mentally aware enough to have tolerated these procedures.

As difficult as caring for my mother has been, my sisters and I want to ensure that she has the kind of death that Coombs Lee describes as respecting ‘a person’s values and priorities, peaceful, pain-free, and gentle’. I keep the paperwork on my desk, within hand’s reach and I still have strong memories of conversations with my mother as we watched news accounts of Karen Ann Quinlan, of Nancy Cruzan, of Terri Schiavo. I know her wishes.

The best advice came from Powell, the bioethicist. She told me to view the legal paperwork as a ‘sacred text’, one that we can interpret with the knowledge of how my mother lived her life. None of us can foresee every medical treatment coming, nor should we have to keep updating advance directives to include new treatments. Powell insists that the spirit of our wishes and how we’ve lived our lives should suffice.

I still want my mother to slip away quietly at home, in her sleep, or in the afternoon while she’s napping in a soft chair. It’s a death she’s always prayed for, when she remembered what prayer was. However, if she ends up in a care facility, I will push hard, if need be, to give her the death she’s entrusted to my care.