When the German banking giant Wirecard collapsed in June 2020 amid a roaring fraud scandal, public opinion was shocked. The company, praised as the country’s innovative answer to the fintech industry of Silicon Valley, had been widely seen as a ‘German miracle’ following recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. Its bankruptcy involved a massive state prosecution that sent shockwaves through world markets. To the astonishment of German and international observers, Wirecard executives were found to be involved in all manner of deception: direct falsification of accounts, fake cash-flows, re-routing of payments through non-existing shell companies, ghost subsidiaries. While forging profits, they had obscured a mammoth debt of €3.5 billion.

This, of course, is not an unfamiliar tale. The explosive growth of finance as a percentage of the ‘real’ economy in recent decades has been matched by an equally dazzling scale of financial fraud, from the Enron scandal to Bernie Madoff’s pyramid scheme (the largest recorded fraud in world history) in the 2000s, to more recent scams in cryptocurrency markets such as FTX. Denizens of finance – both system insiders (Madoff was a former chairman of the Nasdaq exchange) and ‘maverick’ outsiders (Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX had been seen as a challenger of mainstream banking elites) – have displayed a unique capacity for alchemy: whipping up distorted realities in which false truth and true fact become indistinguishable. Their plotting is often aided by regulatory bodies, rating agencies and consultancies that firm up such distorted realities through either action or inaction.

A recent Netflix documentary follows the Financial Times reporter Dan McCrum in his quest to reveal Wirecard’s own big con. The ‘aha’ moment comes when McCrum and his FT colleagues show up at the Singapore address of one of the company’s supposed subsidiaries only to find an unassuming farmhouse. Behind Wirecard’s opaque structure lay simply nothing: no accounts, no offices, no cash. Much of the bank’s alleged business had been conjured out of thin air. Evocatively subtitled ‘a fight for the truth’, McCrum’s bestselling book Money Men (2022), on which the Netflix show is based, offers an animated account not only of Wirecard’s fraudsters, but also of their victims – those led to believe the company bosses and their outlandish myths of stratospheric growth, despite ominous clouds of deceit hovering over. What made a fake story so readily believable by so many? How is it possible that a DAX 30-listed bank (with the backing of Germany’s former chancellor, Angela Merkel, herself) transpired to be a giant Ponzi scheme?

Today’s financial fraud is part of a bigger story unravelling outside of trading floors and corporate board rooms: a growing preoccupation over the nature of reality itself. On one level this preoccupation is fuelled by Big Tech, which has been pumping financial value through innovations ostensibly geared towards tackling ‘existential’ future threats via the production of simulated realities. Facebook’s launch of the Metaverse, an avatar world promising to revolutionise work and everyday life, has been critiqued as a fluke that aimed to distract from the company’s legal troubles, and the more recent release of programs such as ChatGPT and DALL-E by OpenAI intensified concerns about the use of artificial intelligence in Silicon Valley to address fabricated, rather than real, problems.

While some artists, teachers and writers grew uneasy about the increasing ‘realness’ of such AI outputs, others see new opportunities in implementing these chatbots into their work and daily tasks – even though OpenAI has admitted that its ‘large language model’ suffers from so-called hallucination problems: a propensity to cheat by weaving fictitious facts into its answers to user prompts.

Everything appears ‘almost true’ and nothing seems ‘entirely false’

This fuzzy line between authenticity and fakeness is also reflected in social media debates around, for instance Twitter’s use of ‘blue ticks’, originally introduced for identity verification and recently turned into a monetisation tool that made legitimate and feigned accounts harder to tell apart. In popular social media platforms, newcomers such as BeReal strive to capture more spontaneous ‘authentic images’, responding to a growing demand for less staged (yet, still, curated) content among younger users – a feature now incorporated by Instagram and Snapchat. The latest trend in these platforms is ‘dupes’: user forums around fake products mimicking luxury items, which explicitly challenge the distinction between bootleg and original goods (with both being often manufactured in the same supply chains to identical blueprints).

Meanwhile, concerns about ‘fake news’ breed new political conflicts. As a disparate alliance of conspiracy ‘truth-seekers’, New Age entrepreneurs and populist demagogues attack time-honoured certainties and scientific facts, nervous advocates of democratic capitalism strive to expose disinformation and repair our hollowed trust in liberal values. Out of these battles we are often told that a new ‘post-truth’ era emerges, in which material struggles give way to a relentless ‘epistemological crisis’ – as the former U S president Barack Obama put it in the wake of the 2020 election: the dismantling of the means by which we seek and recognise truth. As this state of doubt and confusion takes hold over everyday life, our capacity to tell fact from fiction weakens. Everything appears ‘almost true’ and nothing seems ‘entirely false’.

Contemporary finance has become emblematic of this state of affairs. How true is the reality of mark-to-market accounting practices (the ‘marking’ of fictional future values as ‘present’) used recently by Wirecard and by Enron before that? How real is the wildly fluctuating value of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), the blockchain technologies used to certify authenticity of digital or physical assets traded in exchanges like FTX?

Last February, it transpired that more than 80 per cent of NFTs minted in OpenSea, the most popular marketplace for such tokens, were wash trades (simultaneous sells and buys of the same NFTs creating a false impression of market activity) or straight spam: fake and plagiarised works. Because blockchain asset markets are inherently opaque and built around a belief system that defies ‘real’ valuation – the consensus real set by central banks, ratings agencies and forex trade – they are especially fertile ground for fraud. They often become the stage where traditional forms of scam (such as phone impersonations) are combined with AI technologies (such as those underpinning ChatGPT) to deceive unsuspecting lay investors. In social media, fake celebrity endorsements abound, and ‘pump-and-dump’ schemes artificially inflate the price of crypto-assets before selling them to retail investors.

Despite this, financial wizards have been among the first to take off their gloves and defend their own versions of market reality and truth. Fraud schemes now routinely deploy the well-rehearsed populist rhetoric of ‘fake news’ to respond to allegations of corruption. In the months and weeks before its collapse, Wirecard’s defence line (adopted fully by the German Chancellery and the country’s financial authorities) was that the FT investigation was rigged by short-sellers spreading misinformation for profit. Turning the tables, the company’s bosses pointed the finger to finance itself, blaming their meddling with reality on the ruthless games of greedy speculators. Earlier this year, the Indian commodity trading giant Adani shrugged off similar allegations of market manipulation as fake news sown by market opportunists, who were distorting market reality with bad data – what is commonly referred to in trading as ‘noise’.

Soros suggested that a far wiser move would be to accept the distorted reality of finance

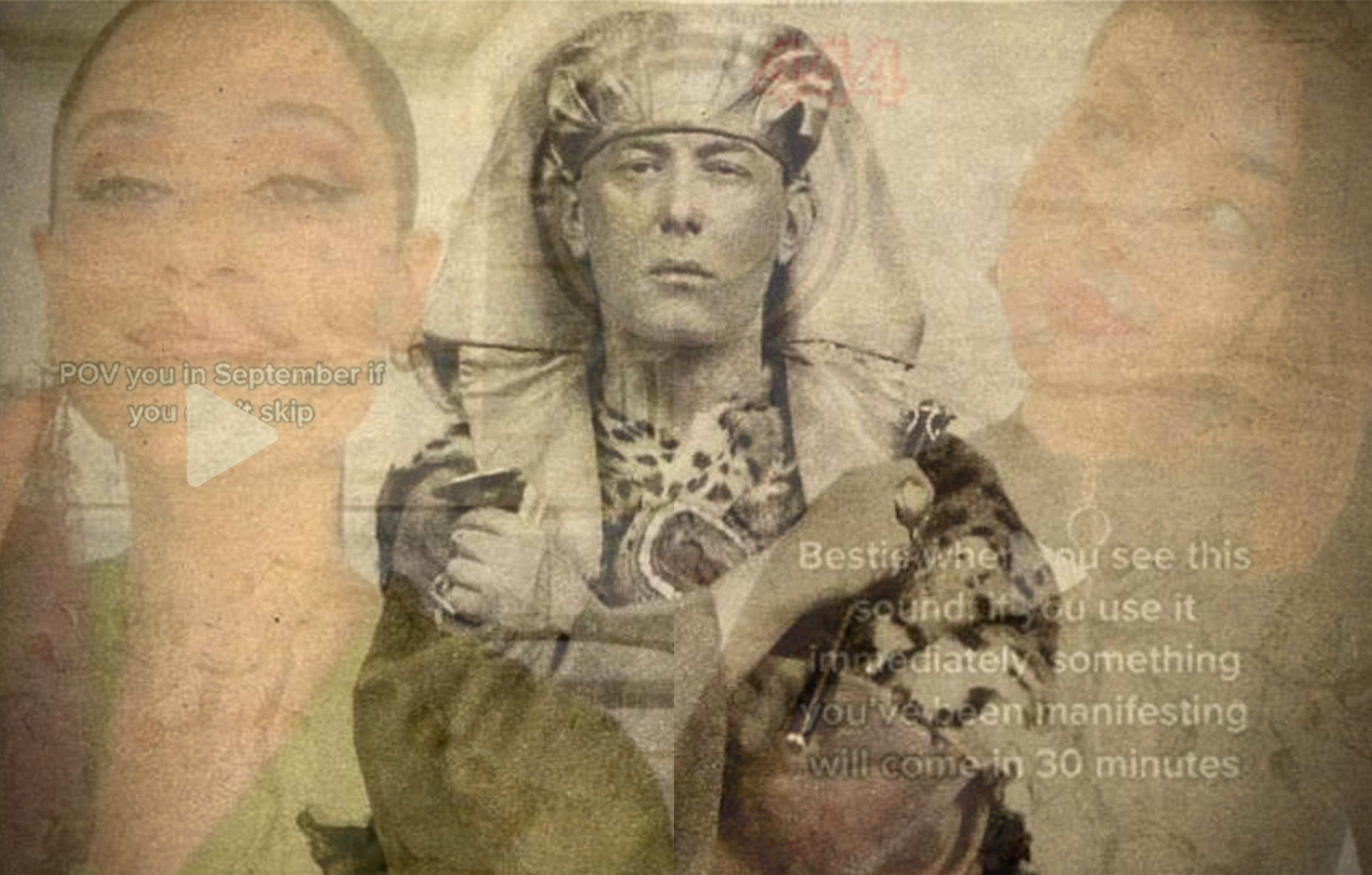

Unravelling the deceptiveness of these worlds appears less straightforward than calling out the lies of fabulists such as Donald Trump or the congressman George Santos. Fraud technologies themselves tend to be spectacularly ‘low fi’ – fake trading at Madoff involved practices as ‘sophisticated’ as manually cobbling together accounts on spreadsheets, keeping cash at office safes, or even hiding it in grocery bags. But finance’s big con hides in plain sight. As financialised culture proliferates and ordinary digital life becomes gamified, the impact of finance on our everyday reality becomes insidious. For those coming of age in today’s middle-class United States, speculation’s augmented reality is only a few scrolls or swipes away from the worlds of gaming, dating, wellness or even the realms of digital astrology and the occult. The deeper we immerse ourselves in the simulated worlds of finance, the more difficult it becomes to explain its alchemy.

One way to make sense of it is to ask how alchemy is imagined by financiers themselves. The leading liberal philanthropist George Soros first took centre-stage during the currency speculation wars of the 1990s, when he gambled against the Bank of England to make an alleged $1 billion profit. In so doing, he became a symbol of greed during a period of unhinged expansion of financial markets. Soros had given important hints of the mindset driving his sensational wagers in his book The Alchemy of Finance: Reading the Mind of the Market (1987).

One year before the publication of Paulo Coelho’s hit novel The Alchemist, the master speculator sought to draw the outlines of financial alchemy. Soros understood it as the capacity to control the fakeness of markets by becoming immersed in it. He challenged the proclaimed association of financial forecasting with ‘hard science’ and quashed mainstream economists’ assumptions regarding the ‘underlying truths’ of market prognostication. Insofar as no financial theory can ever be ‘verified’, he argued, all modelling of price movements can be based only on ritual and incantation – a belief later spurring his infamous ‘discretionary macro’ strategy, which came to be known as a sort of market sorcery. Instead of trying to decipher the unassailable truth of market prices and wrestle it apart from the ‘noise’ of human bias and irrational behaviour, Soros suggested that a far wiser move would be to accept the distorted reality of finance.

He has not been alone in this gambit. Bankman-Fried, the crypto swindler at the helm of the collapsed exchange FTX, allegedly played the popular League of Legends video game while negotiating capital investments. A passionate gamer, he treated the worlds of cryptocurrency markets and action role-playing games with the same knack for plotting. Jan Marsalek, the now-fugitive former boss of Wirecard, had a reputation for evading ‘finer details’ when negotiating trades, often shifting the conversation to diverting stories about Cold War secrets and spies. His zest for casual forgery was not all that different from the tales and rumours greasing the reality of contemporary venture capital. However, rather than simply warping economic ‘facts’, Bankman-Fried and Marsalek also strived to control the forces moulding those facts. Like Soros, they did not aspire to merely interpret ‘the mind of the market’. They sought to re-shape its material reality, too.

The figure of the market alchemist long predates such contemporary villains of finance. The most adventurous confidence tricksters were always to be found in markets: in the fin-de-siècle US, stock touts and tipsters dominated news headlines, stirring fierce debates on the legitimacy and morality of speculation that defined the history of modern finance. Memorable works of fiction during that era at once mirrored and fuelled the public’s fascination with rogue financiers. From Anthony Trollope’s sensational account of Victorian England’s corrupt traders in The Way We Live Now (1875), to Frank Norris’s epic of greed and wheat speculation at the Chicago Board of Trade in The Pit (1903), and from Theodore Dreiser’s fictionalisation of the notorious tycoon Charles Yerkes in The Financier (1912), to Edwin Lefèvre’s celebrated Reminiscences of a Stock Operator (1923), financial fiction invoked an underworld of greed and deception in which ruthless con men reigned supreme. Real figures like Charles Ponzi – the most infamous of all market fraudsters – could have jumped right out of the pages of these novels.

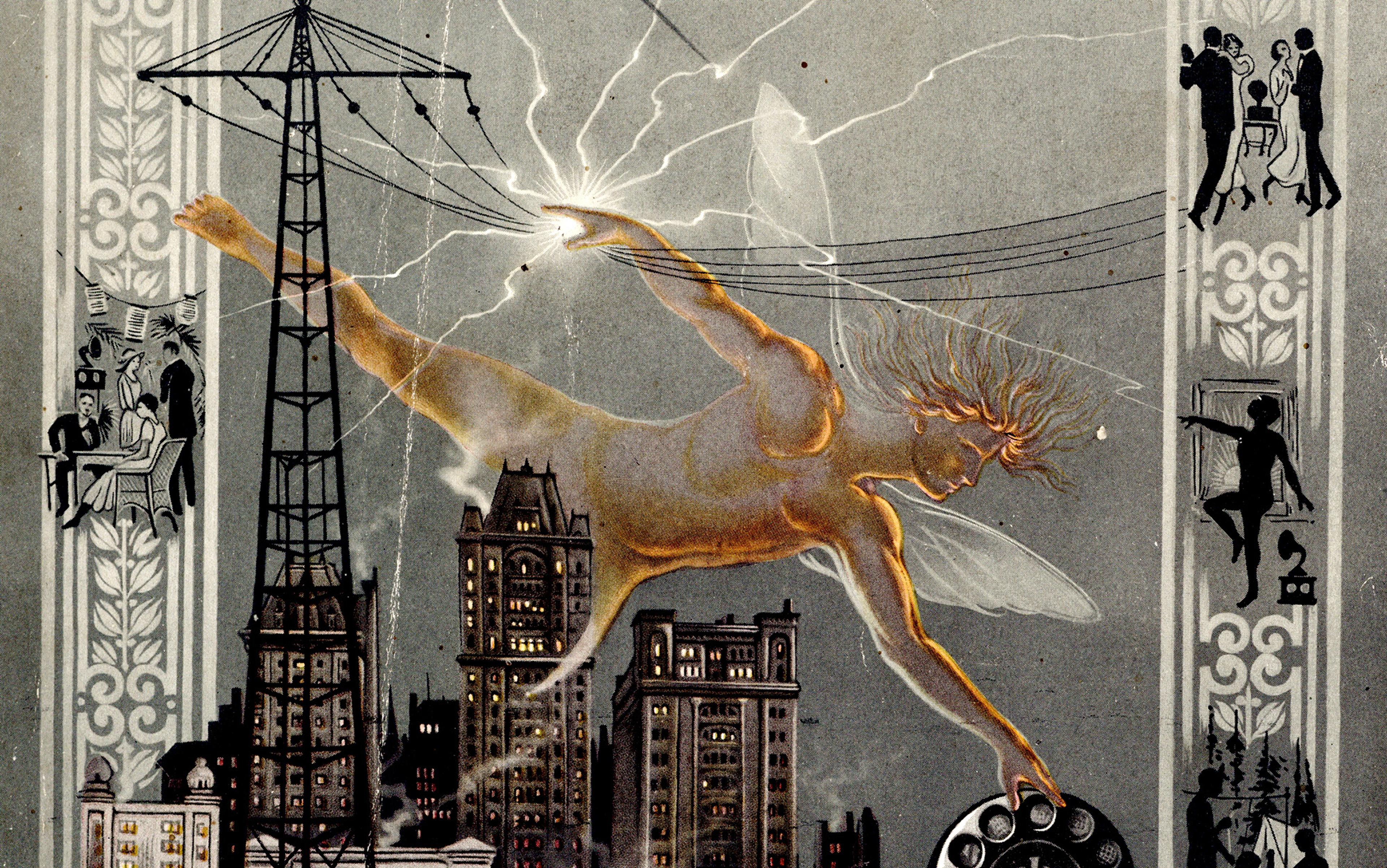

Still, Ponzi and others like him were seen as deviant in ‘efficient markets’ whose hallmark principle of instrumental rationality epitomised the spirit of scientific modernity. The late 19th century was a time when mathematical forecasting took off in earnest in the major stock exchanges in the US. The trading floor became a testing ground for methods of scientific prognostication writ large, including in the fields of meteorology and climate-related prediction. The rise of statistical techniques such as time series analysis, the bell curve and Gaussian distribution revolutionised the study of market price movements, further unmooring it from the material reality of assets. At the dawn of the 20th century, a conviction settled in among traders that stock prices were in some fundamental sense right, their fluctuation conferring a godlike truth.

But while faith in the power of statistical prognostication was growing in the pits, it was not the only method of deciphering finance’s inner truths. The turn of the century saw a renaissance of mystical foreknowledge seeping right into the heart of markets, spawning influential financial practices including ‘technical analysis’ (gaining immense popularity under the aegis of Charles Dow, a co-founder of Dow Jones) and popular trading manuals expounding the virtues of ‘gnostic reason’. Contrary to accounts of markets as cardinal sites of a disenchanted, scientific modernity, fin-de-siècle finance was the stage of a lavish spectacle that swept economic and political life alike. Rather than augurs of a stifling rationality, stockbrokers became the shamans and magicians of a ‘pecuniary enchantment’ – in the words of the historian Eugene McCarraher. Their alchemy, however, did not merely aspire to departures from the material reality of economic doings. Guided by a growing conviction in both material-scientific and spiritual practices, they sought to transmute the base materials of finance (capital, labour) and create a gold-coated reality in the image of markets. In it, their hermetic quests were undergirded by an unwavering belief in market rationality.

Futures trading was legal and desirable because it enabled ‘the self-adjustment of society to the probable’

The great sweep of the traders’ gospel was strengthened through significant developments in US finance over the ensuing decades, most notably the establishment of a national market for financial securities through a widespread distribution of stocks and bonds championed by the government. The promise of more democratic markets encouraged larger swathes of society to reap the benefits of ‘market wisdom’ alongside the professional financiers. However, while the predecessors of today’s securities analysts adeptly reaped the rewards of financial alchemy, those at the bottom of finance’s pecking order were proving more vulnerable to its evils. Economic and political observers of the fin-de-siècle era became gripped by the spectre of ‘irrational crowds’: mobs of market dwellers purportedly marred by manias, panics and delusions, and thus prone to manipulation and deception.

This negative view of the world of lay finance was bookended by Charles Mackay’s 1841 account of ‘manias’ in Victorian-era markets and the historian Richard Hofstadter’s damning 1960s treatise of the Populist Movement as a ‘paranoid style’ of politics: collective action taken by exuberant publics who were led astray by misinformation, gossip and hearsay. If professional financiers were seen as competent helmsmen in turbulent speculative markets, amateur bettors were cast as deluded crowds threatening market stability. Their ‘noise’ was seen as a distortion of market reality, an inflection of the fundamental truths summoned by the signals of stock prices. The early period of market ‘democratisation’ had let the genie out of the alchemist’s bottle, and the fever of speculative finance was spreading to thousands of ‘bucket shops’ in the far corners of the US.

But the trading of commodities did not merely excite publics by fuelling their speculative longings. It also invited them into a ‘marketplace of ideas’ that bolstered the vision of liberal democracy that came to define 20th-century politics. The term itself is often traced back to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and his 1919 ruling in the Abrams v United States Supreme Court case, in which he asserted the superiority of the truth defined by market competition.

This avowal was not incidental – it reflected the broader convergence around the ideas of democracy and speculative finance that were congealing in US capitalism. A few years earlier, Holmes had been a key figure behind a lesser-known – yet just as influential – Supreme Court ruling: the 1905 Chicago Board of Trade v Christie Grain & Stock Co, which declared futures trading (the most speculative kind of financial activity) legal and desirable because it enables ‘the self-adjustment of society to the probable’ (thus distinguishing professional exchanges from the lay trading in bucket shops, which he regarded as pure gambling). Sanctioning the enchanting world of markets while asserting its vast power inequity conferred on financial alchemy an enduring force that is still with us today.

Our time’s market alchemists, like their forebears in the postbellum stock exchanges, are typically seen through the binary of fraud: the flip side of institutional norms assumed to be constant, fair and tending towards equilibrium. Popular depictions of high-octane finance continue to focus on stories of smoke and mirrors woven around lies and greed – and they do so for a good reason. But by singling out the ‘excess’ of a few fraudsters, they ultimately distract us from the messier reality of finance, where alchemy is at the core, not an outlier. The ways in which Madoff and Bankman-Fried steered their multibillion scams through global markets were not as much a deviation from that reality as a window into it. Because markets are worlds where noise and signal are impossible to distinguish, the boundaries between real and fake are much more porous than what is assumed in mainstream accounts of fraud.

This, as I hope to have shown, has been the case throughout the history of a modern finance capitalism powered by alchemy. But it has become especially pronounced in our time, because contemporary forms of (computational, quantified) finance thrive in the uncertain space of big data and correlation, where noise reigns supreme. Fraud becomes both more insidious and harder to parse out in this context. Financial alchemy, in that sense, is more akin to distortion than to deception. Rather than a neat movement from facts to fibs, it represents an ambivalent coexistence of truths and falsehoods, which – as is often the case in today’s gamified markets – can even embrace fakeness. From J P Morgan’s avowed passion for astrology during the Gilded Age, to contemporary bankers’ enthusiastic endorsement of memetic NFTs, the history of finance brims with distortions that make no totalising claims of truthfulness. Financiers have long understood themselves as performers of alchemy, often being entirely transparent about their own gimmicks.

Today, paradoxically, it is this open admission – the ‘exposure of the trick’ – that makes financial alchemy even more effective. Its mass appeal emanates from being rooted into our volatile social and cultural worlds. In them, opacity and spectacle so often become accepted features of everyday reality. Far from dupes in the grip of ‘collective hallucinations’, modern financial subjects have been entwined with the forces of alchemy in much more dynamic, imaginative – and, often, wilful – ways. Their collective expression has produced a politics rich in myth, stretching today from outlandish conspiracy movements like QAnon, to TikTok communities of ‘vibes’, and gaming and crypto-trading subcultures.

It is for this reason that calls to break the spell of financialisation in everyday life offer insufficient answers to our so-called ‘post-truth’ moment. The ghosts of mob psychology and irrational exuberance have continued to haunt our perceptions of fraud and financial deception. But the present ‘reality crisis’ demands greater sensitivity towards the capacity of market distortion to create absorbing other-worlds. Distortion has been a critical force across fields as diverse as scientific and cultural production, from data science to music. Interpreting signals has been closely entangled with studying the generative possibilities of ‘noise’: looking for an ally in the glitches, dupes and ‘bad data’ that inhere within all forms of life and permeate our technologies of representing truth. At stake in the ‘fake worlds’ of financial alchemy is not merely resisting their will to deceive us but understanding their capacity to condition our struggles for other, more democratic realities.