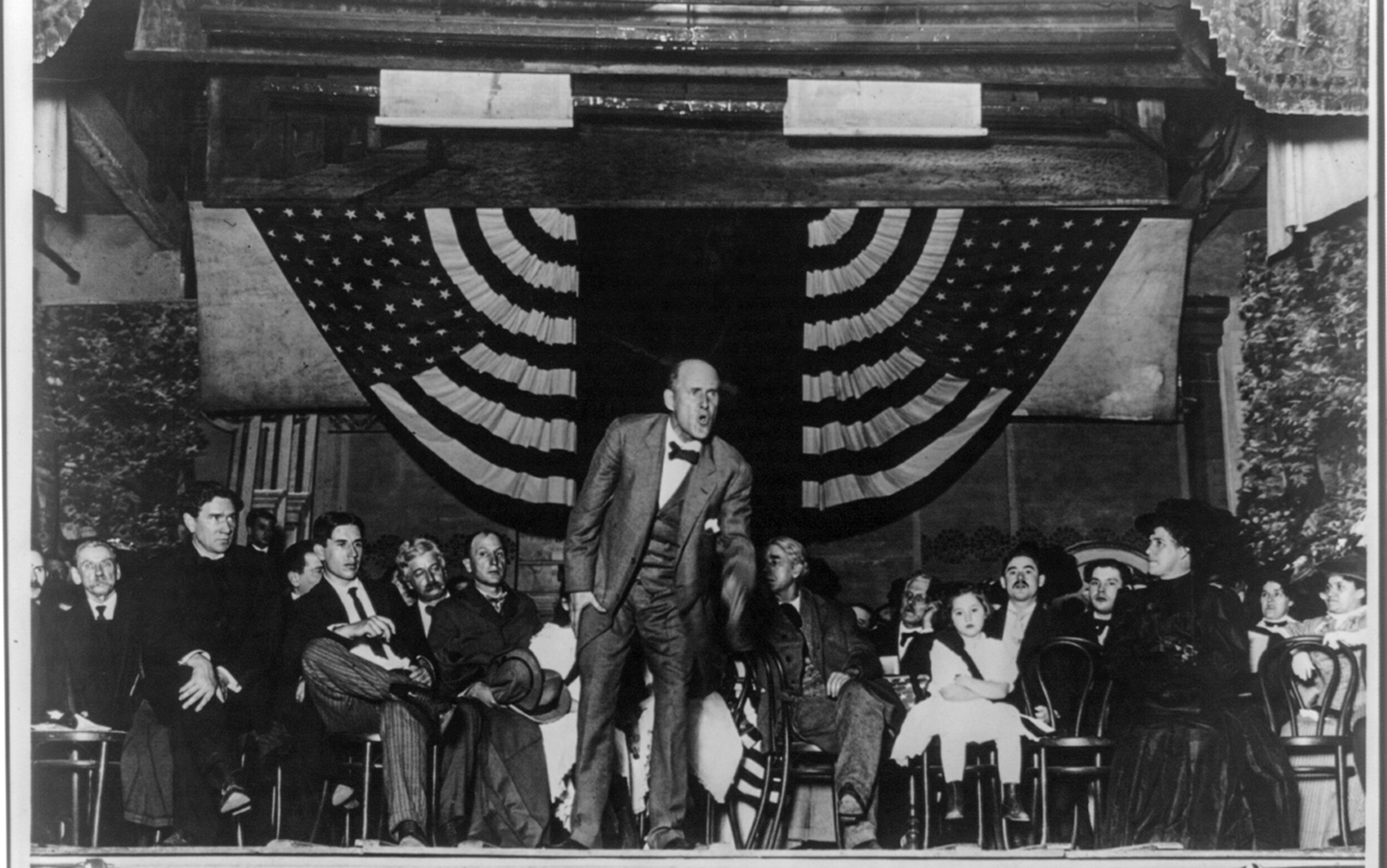

A shot rang out from the jailhouse at Woodstock, Illinois on a quiet summer’s morning in 1895. One of the inmates had pulled the trigger on an old Civil War musket after thrusting it between the iron bars of a window. The gun was fired by the union leader Eugene V Debs to mark the Fourth of July: this was no prison break, but a demand for another kind of freedom. Later that day, he would write in praise of liberty, while delivering the grim verdict that, in the United States, it now ‘lies cold and stiff and dead’. Soon to be the country’s most influential socialist, how had Debs come to find himself contemplating the prospects of US liberty from behind the bars of McHenry County Jail?

Debs’s story is more than mere biography: it speaks to the wider struggles of the US working class, who were facing the harsh new realities of industrial capitalism. But it must be admitted that the man himself cut a striking figure, being possessed of great charisma, courage and powers of speech. His French immigrant parents found their way from Alsace to Terre Haute, Indiana, where little Gene was born in 1855. Something of the frontier spirit still survived in the small city, which had not yet suffered the sharp class divisions that were visible elsewhere in the country. Although Debs left school at 14 – heading to the railroad to scrape paint and grease for 50 cents a day – his education acquainted him with a republican history of the US, which held the liberty and sovereignty of its citizens in the highest regard.

Eugene V Debs (seated, far left, appropriately) aged 14 with fellow painters at the Vandalia Railroad in Terre Haute, Indiana, 1870. National Archives and courtesy the Debs Collection, Indiana State University, Cunningham Memorial Library

Graduating from the paint shop to a job as a locomotive fireman, his mother pleaded with Debs to quit the railroads after an accident killed two of his colleagues. An abysmal safety record and negligible compensation for injured railwaymen were just some of the many indignities of the ruthless business practices of avaricious industrialists. Before wisely heeding his mother’s warnings, Debs joined the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, subsequently rising to become its Grand Secretary and editing the widely read Firemen’s Magazine for well over a decade. From this editorial perch, he could be far from militant, initially opposing strikes and delivering moralistic sermons on the Brotherhood’s motto of benevolence, sobriety and industry. His new prominence would even lead to his election as a Democratic member of the Indiana House of Representatives in the mid-1880s. But sensing the limitations of both the state legislature and the conservative craft unionism of the Brotherhood, he sought a different vehicle to advance the interests of railroad workers.

What began to disturb Debs was the despotic power of corporations and the judicially sanctioned violence that could be unleashed on workers who resisted attempts to sack them or suppress their wages. As he later remarked, their combined influence let loose ‘deputy marshals armed with pistols and clubs and supported by troops with gleaming bayonets and shotted guns’, and has ‘vanished liberty from the land.’ He came to feel that citizens could no longer be counted as free when they were under the thumb of a plutocratic ruling class backed by a corrupt judiciary and the violence of hired ‘Pinkerton’ strikebreakers, with helpless workers even coming to resemble slaves. That language of slavery was shocking, even hyperbolic, but it allowed Debs to associate the plight of workers with the two great republican bids for emancipation in the country’s history: the fight for independence against the political slavery supposedly imposed by the British, and the more recent attack on chattel slavery that had led to the Civil War.

On the railroads, the insular craft unions, who organised separately according to job roles, seemed doomed to irrelevance in the face of the titans of industry. Leading the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers in the failed Burlington railroad strike of 1888, where several workers were killed, brought home to Debs the bitter limits of this kind of organising. So he gradually broke with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers in order to help found the American Railway Union in 1893, which aimed to unite all those who worked on the railroads, while enjoying rapid growth ahead of an early victory on the Great Northern Railroad. This set the scene for the Pullman strike that would propel Debs to national fame and put him on a collision course with a powerful coterie of economic, legal and political elites.

George Mortimer Pullman was an industrial magnate who manufactured railway sleeper carriages from his company town of Pullman on the outskirts of Chicago. He set the rents of the houses in which his workers were required to live, and imposed a strict moral code on them, including discouraging alcohol and gambling. When a nationwide financial panic hit in 1893, Pullman made dramatic cuts in wages while maintaining rents at their existing levels. Workers were squeezed dry, and they braced themselves for a desperate fight for survival. The ensuing conflict drew in the American Railway Union, which eventually called a boycott of trains that continued to carry Pullman carriages. The federal government responded by obtaining an injunction to stop strikers interfering with the railways, and specifically the free traffic of mail cars.

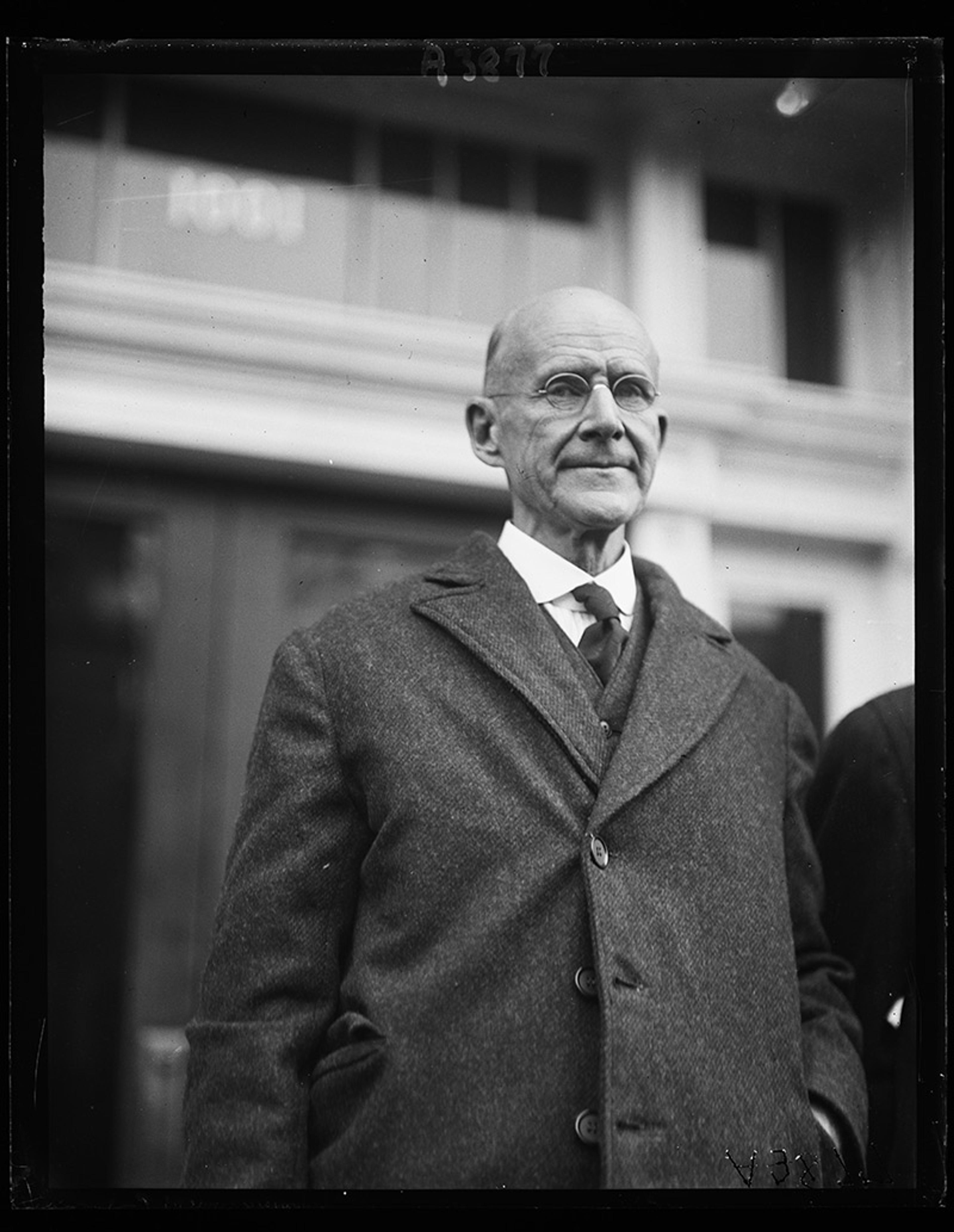

Eugene V Debs c1922-23. Courtesy the Library of Congress

The leaders of the American Railway Union, including Debs, did not stand down. Their fate was sealed by the Supreme Court upholding an earlier decision to jail them for contempt of court. What most outraged Debs and his fellow defendants was that no jury had convicted them of a crime. They had been incarcerated at the ‘autocratic whim’ of a federal judge, with no opportunity to plead their case in front of ordinary citizens. If Debs could be locked up so easily, he reasoned that his fellow citizens were unfree too. But the courts were not the only arbitrary authority that must be fought in order to be free.

The rise of an industrial capitalism in the closing decades of the 19th century created a breeding ground for unaccountable power. Waged workers in particular were at the mercy of their wealthy employers, who determined whether they would earn enough to house, clothe and feed themselves and their families. Without the safety net of a welfare state, the discretion to dispense with labourers effectively gave wealthy industrialists the power to impoverish workers who demanded better conditions or were simply deemed surplus to requirements. The huge fortunes of industrial millionaires also granted sweeping political influence, whether through outright bribes or more subtle webs of influence. In mounting these criticisms, Debs took himself to be following in the footsteps of a longstanding republican tradition in the US, which lauded the freedom of its citizens. Yet his own path through the labour struggles of the Gilded Age would lead Debs to a more radical destination than his republican forebears. He demanded an unequivocally socialist republic in which all could be free.

Debs turned the language of republican thought against bosses and the system that sustained their power

Many know republicanism best today as a rejection of monarchy – a commitment Debs eagerly shared with earlier generations of Americans who parted with King George III. But hostility to royal authority is only a small part of a much richer republican philosophy that stretches back to the ancient world. Republicans stand for the freedom of citizens who can come together to pursue the common good. The great evil they recognise is subjection to another’s arbitrary will. Someone who has to depend on sheer goodwill lacks freedom, even if they happen to be treated well. Such a person acts at the mere indulgence of others. That is the servile condition of chattel slaves and subjects of absolute monarchs, no matter how kindly or enlightened their masters are.

The freedom of the citizen has always been precious to republicans. But the bounds of that citizenship could be drawn narrowly, with no space for women, the poor or those outside a ruling racial caste. Thus, to the glee of fellow critics of a fledgling American republic, Samuel Johnson could ask: ‘[H]ow is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?’ However, a century later, Debs would recall abolitionism with pride, organise across racial lines, and align himself with the cause of women’s suffrage. From early in his career as a labour organiser, he even claimed to be tackling ‘wrongs which take on some of the forms of slavery’.

Back in the 17th century, the English republican Algernon Sidney claimed that to ‘depend upon the will of a man is slavery’. Drawing on ideas with classical roots, he was warning about the unaccountable power of monarchs (with good cause, given his own subsequent beheading for treason). Sidney’s writings have been dubbed a ‘textbook of revolution’ and, partly through his influence, we find framers of the US Constitution such as Alexander Hamilton distinguishing liberty from a state of slavery in which someone is ‘governed by the will of another’. The very possibility of unlimited British taxation without representation in their parliament could seem to fit the bill. But neither Sidney nor Hamilton would defend the plight of servants or hired labourers in these republican terms.

Debs turned the resonant language of republican political thought against bosses and the whole system that sustained their power. Like republicans of old, he warned of a fatal dependence on the arbitrary will of others. But rather than attacking the untrammelled authority of a king or overseas legislature, he adapted this analysis to the conditions of a rapidly industrialising capitalist economy. There could be no political equality when workers were dependent on capitalists who owned the resources, tools and machines needed to make a living. Debs would conclude that: ‘No man is free in any just sense who has to rely upon the arbitrary will of another for the opportunity to work.’ But that unfreedom was the reality for most working people, who laboured and therefore lived by the permission of bosses.

Control became key to how Debs understood work under capitalism. The long hours, unsafe conditions and exhausting nature of much of this labour was not lost on him. As a former locomotive fireman, shovelling coal into the fire-box of a rail engine, Debs knew what gruelling work meant. Nor did he have any illusions about the bleak conditions among the mills, factories, mines and farms where, day after day, workers slogged their guts out for a meagre reward. But Debs’s complaint was more fundamental than poor working conditions or even low wages – it took aim at the lack of freedom at the heart of the economy.

Republicans want to eliminate arbitrary power, not entrust it to wise and kindly rulers. In this spirit, Cicero remarked that ‘freedom consists not in having a just master, but in having none.’ Sidney would add: ‘[H]e is a slave who serves the best and gentlest man in the world, as well as he who serves the worst; and he does serve him if he must obey his commands, and depends upon his will.’ Debs saw that this was the plight of those workers who desperately needed a wage and could not buck the strenuous discipline of employers that came with it. Such a life was lived at the mercy of others, whose favour or displeasure could determine whether families could eat or put a roof over their head. To be so squarely under the thumb of a class who could see that you starved – and so to have many masters rather than a solitary owner – is to begin to taste at least some of the characteristic unfreedom of the slave.

If freedom was the destination, the solution to such vulnerability could not be nicer bosses brimming with paternal affection for their workers. Control must instead rest with citizens rather than plutocrats and their minions. This conviction led Debs to a socialism that sought to secure economic freedom for all. Finding himself in another courtroom towards the end of his life, he set out this socialist demand:

[A]ll things that are jointly needed and used ought to be jointly owned – that industry, the basis of our social life, instead of being the private property of a few and operated for their enrichment, ought to be the common property of all, democratically administered in the interest of all.

That conclusion was not the product of the giddy enthusiasm of youth or a life of detached scholarly study. It was wrested from a tireless struggle in support of workers being chewed up and spat out by a capitalist economy and the plutocrats who it enriched.

Debs’s time in McHenry County Jail was a point of inflection in the development of his political thought. Confronting the combined power of industrialists, the government and the judiciary, while ending up imprisoned for his troubles, led Debs to think more seriously about what kind of society would allow people to be free. That his answer was socialism might surprise us. Perhaps a socialist society would be more equal, perhaps even more just, but why think it would be freer? Won’t the clunking fist of the state actively deprive people of their liberty by appropriating their property and pushing them around? Debs did not see it like that, and had some impeccably republican grounds for his judgment.

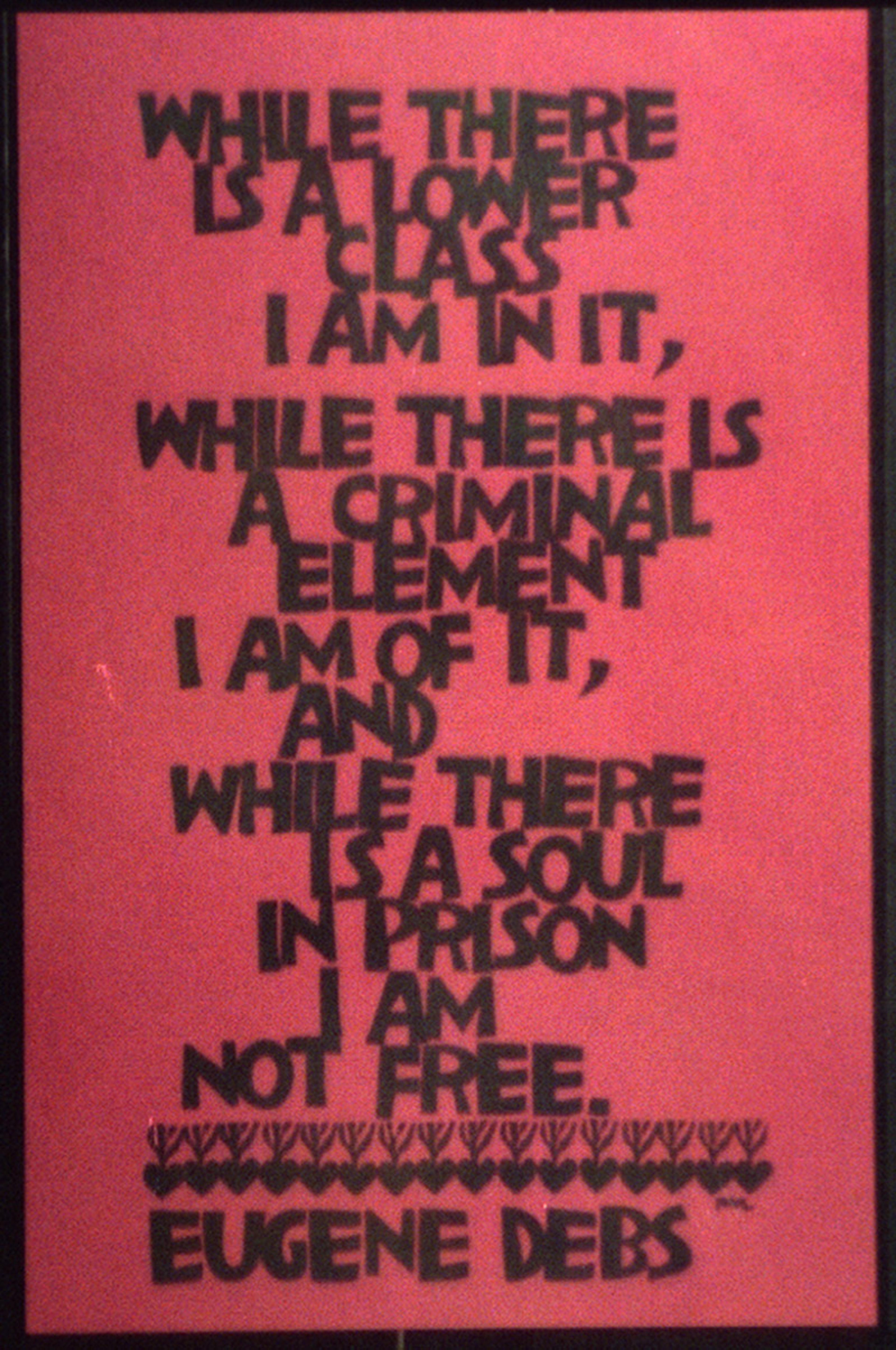

A poster from 1965 incorporating one of Eugene V Debs’s most noted slogans. Courtesy the Library of Congress

There is a long republican tradition that associates freedom with property. The ancients often assumed that liberty depended upon having the time for leisure and political activity granted by ownership of land and slaves with which to work it. Economic independence became the material foundation of freedom, and itself rested on secure possession of private property. Modern republicans can be found taking up the call for land for citizens more broadly – lauding the independent yeoman or homesteader, who appears somewhat insulated from the arbitrary power of others, insofar as they can provide for themselves through their own labour. Another model of the economic security needed for freedom was the artisan who owned their own tools and workshop. But both agrarian and artisanal independence were increasingly threatened by industrial society. Debs recognised that in the age of the factory, railroad and mass-market goods, there was no hope in clinging to this already romanticised past: the future of economic production would be inescapably social and interdependent.

After reading socialist writings during his incarceration at Woodstock – above all, Karl Kautsky – Debs was increasingly convinced of the need for a cooperative economy that took power out of the hands of plutocrats and gave it to ordinary citizens. He was not the first member of the US labour movement to have such thoughts or to frame them in republican terms. The Knights of Labor, an influential nationwide labour federation that reached its height in the 1880s, had called for a cooperative commonwealth. They were labour republicans, who believed workers were effectively rendered slaves by their subjection to the will of employers. If this dominating control was to be eliminated, citizens would have to ‘engraft republican principles into our industrial system’, rather than reserving them for politics alone, as the labour leader George McNeill put it.

Under such a system, working life would be geared not to profit but to human needs

The Knights set up many cooperatives owned by workers themselves, but these experiments eventually ran aground. Debs concluded that something more ambitious was needed: the genuinely collective ownership of the means of production and distribution. If all citizens have a stake in the economy, without unaccountable bosses who could sack them whenever it proved profitable, then people would possess the economic security necessary to be counted as genuinely free. Furthermore, in the workplace itself, workers rather than capitalists could govern how labour was organised, and so not be subject to the whims of owners who were not answerable to those they employed.

Debs arrives at a socialist republicanism. While freedom borne of control over property remains central to this republican story, this is no longer private property. Instead, ‘Economic freedom can result only from collective ownership.’ A real republic, according to Debs, cannot restrict democracy to narrowly political affairs, but must be founded on an economic democracy. Under such a system, working life would be geared not to profit but to human needs. Nor would anything of great value be lost, since we ‘no more need owners of the railroads and other great machines than we need a king.’ This was the ethos that informed the Socialist Party of America (and its forerunner, the Social Democratic Party of America), which Debs helped found in 1901. He was their US presidential candidate five times, and secured 6 per cent of the national vote in 1912.

This turn to electoral politics was not only motivated by the opportunities for propaganda afforded by electoral campaigns but the realisation that political office was needed to definitively transform the country. Yet, this did not imply a rejection of the union activity to which Debs had devoted much of his life. Just as he had turned from craft unions segregated by job type to the industry-wide American Railway Union, Debs came to embrace an even more capacious model of industrial unionism that sought to bring together the whole working class. Thus, along with many of the most influential members of the US labour movement, Debs contributed to the creation of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905. They were committed to abolishing waged labour and ultimately sought to construct a ‘new society within the shell of the old’.

Debs’s magnetic appeal was not confined to his timely political programme but flowed from an impassioned and empathetic character. His speeches were legendary, with working people being left in no doubt he would always fight alongside them. But he hated demagoguery, and would often stress the importance of self-education and following one’s own conscience:

I am no labor leader. I don’t want you to follow me, or anyone else. If you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I could lead you in, someone else could lead you out. You must use your heads as well as your hands and get yourself out of your present condition.

This is a socialism from below. Fatherly leaders directing the class struggle with their superior foresight were not what was needed. The working class must instead free itself, while drawing its strength from the democratic energies of workers and citizens as a whole.

He would get close to a million votes as a presidential candidate in 1920 while still a prisoner

Nor did this concern for others stop at the country’s borders. Despite his opposition to Prussian militarism, Debs believed that the First World War was a senseless disaster for the working classes of all the nations involved. In a fiery speech in Canton, Ohio in 1918, he articulated his opposition to the war. Before a fortnight had passed, Debs was arrested for sedition, then put on trial and sentenced to a decade in prison, after the court found that he had sought to obstruct military recruitment. Upon his conviction, Debs made one of his most widely known pronouncements:

[W]hile there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

It was this sincere identification with the oppressed that won Debs such a hearing throughout his political career. Indeed, he would get close to a million votes as a presidential candidate in 1920 while still a prisoner and unable to conduct rallies or give speeches. His victorious opponent in that contest, Warren G Harding, eventually commuted his sentence to time served, with Debs being released on Christmas Day 1921, after spending more than two and a half years inside.

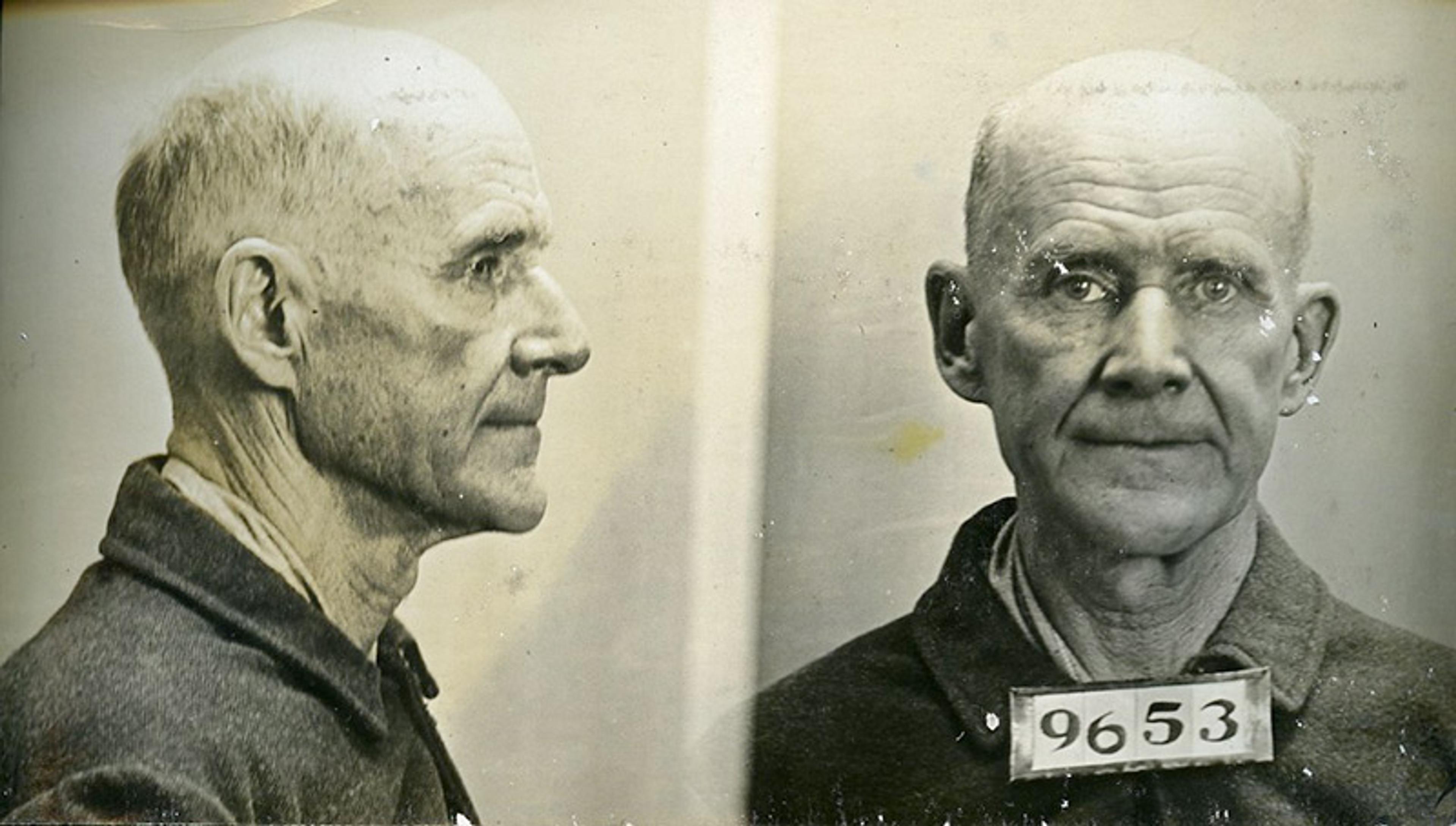

Convict No. 9653 at the US Penitentiary, Atlanta, where he was sentenced to 10 years for sedition. Courtesy National Archives at Atlanta, RG 129

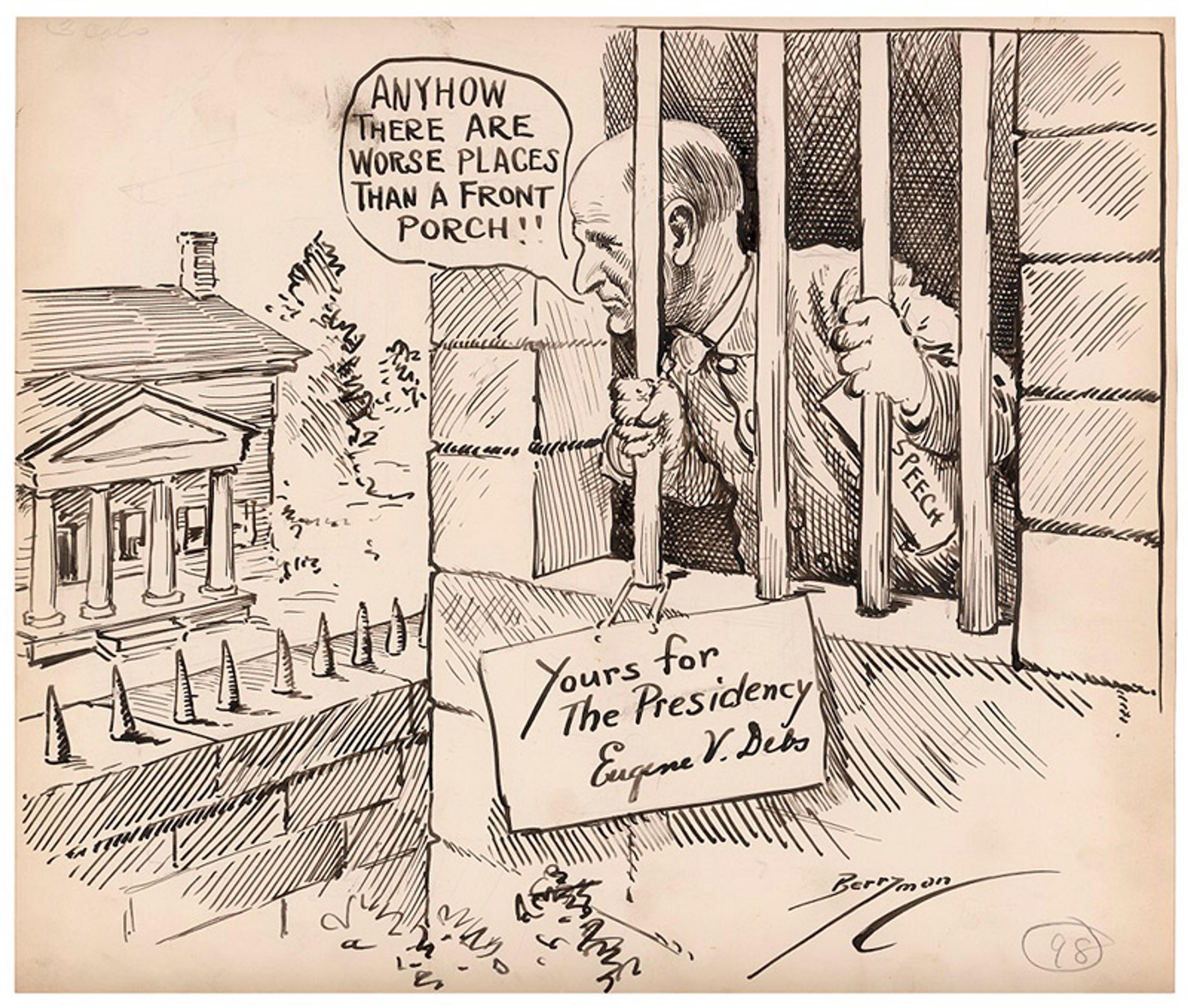

A political cartoon featuring Eugene V Debs in his cell; the ‘front porch’ comment refers to Republican candidate Warren G Harding’s conservative presidential campaign. Courtesy National Archives

Eugene V Debs on Christmas Day 1921 outside Atlanta Federal Penitentiary upon his release. Courtesy Library of Congress

This was not the first time Debs had been imprisoned. But this longer and more onerous stay led him to reflect at greater length on the conditions of prisoners and the place of criminality within a socialist society. The main function of law, he believed, was to keep the poor in subjection to the ruling class, and most prisoners owed their sentences to the poverty thrust upon them by the demands of a capitalist economy. In an early statement of what we would now call ‘prison abolitionism’, Debs held that prisons in anything like their current form would and should be eliminated by a socialism that stood for human liberty. Theft, in particular, would dwindle when the economic subordination created by capitalism was replaced by cooperative production and common ownership. Other crimes that remained ought to be handled by civilised institutions rather than through the brutality of prison life.

Debs’s often-frayed health had suffered from incarceration, and did not hold for long after his release. Slowed by cardiovascular problems, he died less than five years later at the age of 70 in 1926. But he left a vivid legacy, not only in a life that has inspired later US socialists such as Bernie Sanders, but in an intellectual if unscholarly contribution to republican and socialist thought. The promise of liberty – of free citizens not subject to the whims of bosses, judges and a plutocratic class – was not to be found in the anarchy of market competition. Instead, it required us all to have a democratic say in how the economy is governed, and the workplaces where we spend so much of our lives. That vision asks people to break with the desperate attachment to private property that has become second nature to so many of us. True security, and the liberty-giving independence of thought and action that it brings, rests upon a deeper act of solidarity, where we learn to cooperate in our economic lives rather than dance to the tune of profit. Debs held that the path to freedom runs through the institutions of a socialist republic.