At a cotton plantation in Louisiana owned by Bennet H Barrow, in 1841 and 1842, ‘a total of 160 whippings were administered, an average of 0.7 whippings per hand per year.’ Or so calculated the economists Robert Fogel and Stanley L Engerman, drawing on tables created by the historian of Louisiana Edwin Adams Davis, from the owner’s diaries.

The economists put forward this number, among many others, in a controversial revision of the historiography of slavery, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery (1974). The book was marketed to attract a wide audience, project scholarly authority (the footnote-free volume was accompanied by an equations- and table-rich supplement) and arouse controversy. The inevitability of the Civil War was at stake. And along their way, starting with the neoclassical model of a rational slave-owner, showing that the plantation business was profitable, the authors went so far as to write that:

Planters sought to imbue slaves with a ‘Protestant’ work ethic … Such an attitude could not be beaten into slaves. It had to be elicited.

They also minimised the sexual abuse of slaves and the separation of families.

Debates about Time on the Cross have cast a long shadow on the relationships between economists and historians in the United States. Fogel and Engerman depicted themselves, and are still heralded by many, as heroes of a ‘new economic history’ – also called ‘cliometrics’ – that would use numbers and models to make history more efficient. They argued that National Science Foundation grants which could fund teams of assistants would ultimately disprove the theses of older historians. Meanwhile, most historians in the 1970s dismissed not only the book’s assessment of slavery but its quantitative methods generally, for their lack of consideration of the complexities of human experience and agency. This was, in fact, just another episode in a decades-long war. Why would there be battles about numbers in history? Because quantitative methods have long been a signal and symbol of much more than numeracy, or computer proficiency. Scientific disciplines often develop through wars along binary divides, and ‘quantitative vs qualitative’ is a classic. This becomes a problem when each entrenched camp remains static.

There have always been exceptions, though: daring scholars who crossed the battlefield to explore or create new territories. Among the outraged academics who wrote hundreds of pages to refute Fogel and Engerman’s hypotheses and evidence was the social historian Herbert G Gutman, a specialist of African American families who did not hesitate, in his own research, to translate original sources into numbers. Not any number would do, however. As Gutman pointed out in Slavery and the Numbers Game (1975), it made no more sense to talk about receiving 0.7 whippings per year than it would to write that 99.998 per cent of Black people living in the US were not lynched in 1889. Another way to look at the average of 0.7 was to calculate that each slave in the plantation witnessed a whipping every 4.56 days – that of a man once a week, plus a woman once every 12 days. So much for elicitation as opposed to threat.

That there is more than one way to interpret numbers might seem obvious, but is worth repeating at a time when, once again, historians claiming that they will emulate the supposedly ‘hard’ sciences are in a position to get huge grants and hire armies of assistants. Sketching the history of the numbers wars might be a way to avoid, once again, pitting a hard, scientific, male, simplistic, materialistic quantification against an ambiguous, painstaking, female, complex, humanistic history – a way towards less boring books and articles.

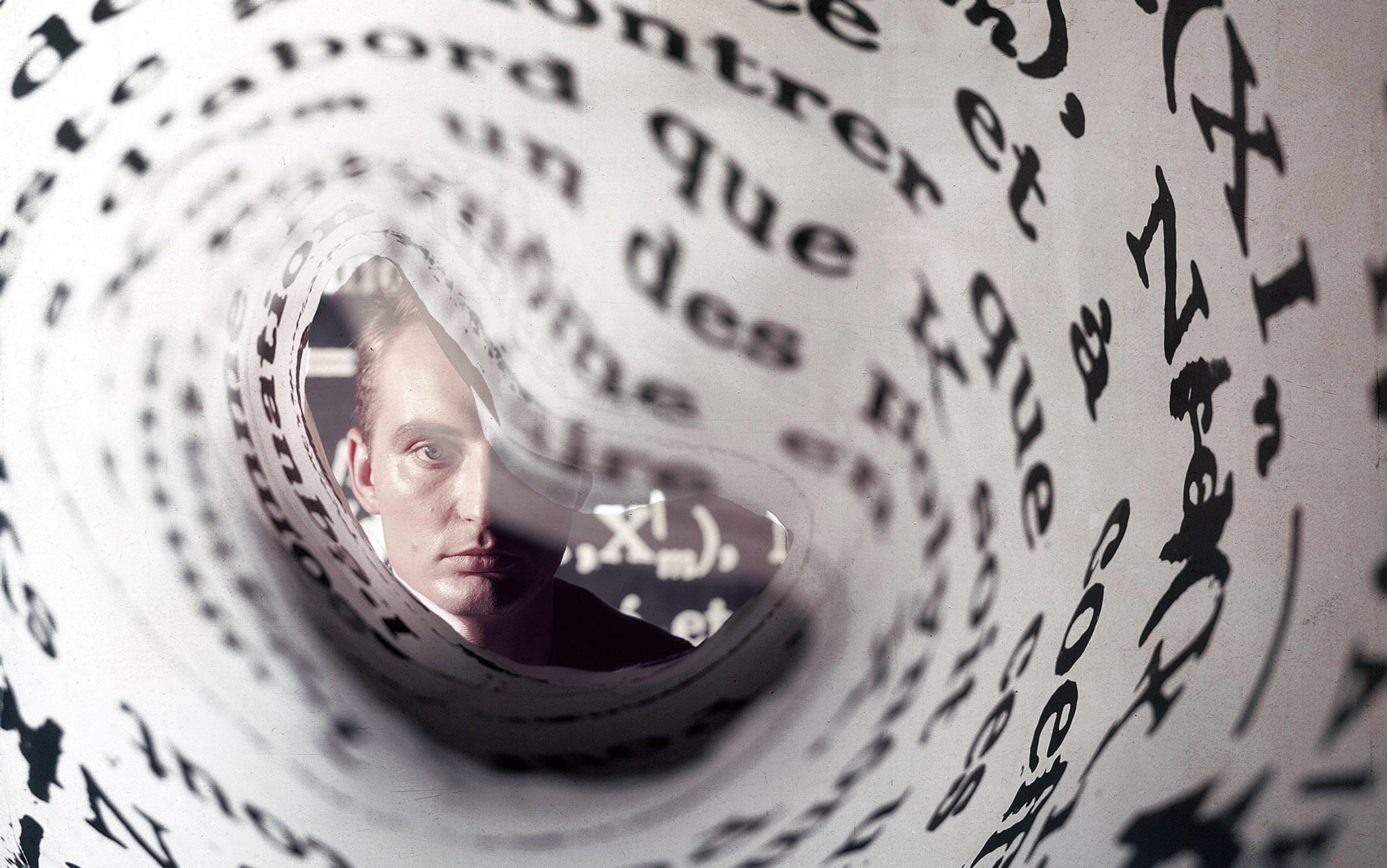

‘The historian of tomorrow will be a programmer, or he will not exist,’ wrote Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie in 1968. Those were the heydays of a fashion for quantitative history shared in many countries and specialties; it was branded as ‘new’: not just ‘new economic history’ but also ‘new social history’, ‘new political history’. The novelty could be questioned: there had in fact been punch-card history in the previous decades and, as early as 1903, the young French sociologist François Simiand had set the tone of the verbal war. He publicly attacked Charles-Victor Langlois and Charles Seignobos, renowned history professors and the proponents of source criticism (then a new method, still a standard of the historical profession today).

Simiand indicted the three ‘idols of the historical tribe’: ‘the political idol … the individual idol … [and the] chronological idol’, and the historians’ non-scientific view of causality. On the contrary, sociological methods, ie, statistics, would allow historians to reveal persistent basic phenomena, especially in economic history, instead of focusing on biographies of leaders or on battles. This episode set the tone for the numbers wars. Numbers would be on the side of real science, history from the bottom up, and/or long-term tendencies in material life. On the other side, trying to nuke ‘that Bitch-goddess, quantification’ in 1963, Carl Bridenbaugh, the president of the American Historical Association, spoke in defence of ‘a sense of individual men living and having their daily being’, ‘comprehension’ and ‘chaps’.

Bridenbaugh’s speech was unequivocally conservative, but quantitatively oriented ‘new historians’ had very diverse politics and theories, from the Marxists to neoclassical economists. What they all took part in was an international trend toward positivism in the social sciences. ‘New social historians’ focused on people, themes and sources that had previously been mostly dismissed by mainstream historians: they used tax registers, records of marriages and so forth to capture the whole range of ordinary people’s life experiences. But they often considered those ordinary people in the aggregate, as constrained by objective ‘social structures’ of which they were incompletely aware. The keyword ‘structures’, be it used to refer to class struggle or to the typical size and arrangement of households, suggested that details did not matter much. Nor did individual human agency.

‘New historians’ had confidence in 20th-century statistics and ranked the ‘reliability’ of sources accordingly. The more massive and homogenous, the more suited to contemporary categories, the better; other features of the sources were problems to be fixed. In 1955, one of the pioneers of ‘new political history’, Walter Dean Burnham, published almost 1,000 pages of data on presidential ballots, 1836-92. Similar books still commonly appeared in the 1980s.

Radical scholars were not satisfied with writing a history of the masses; they sought to recover individual voices

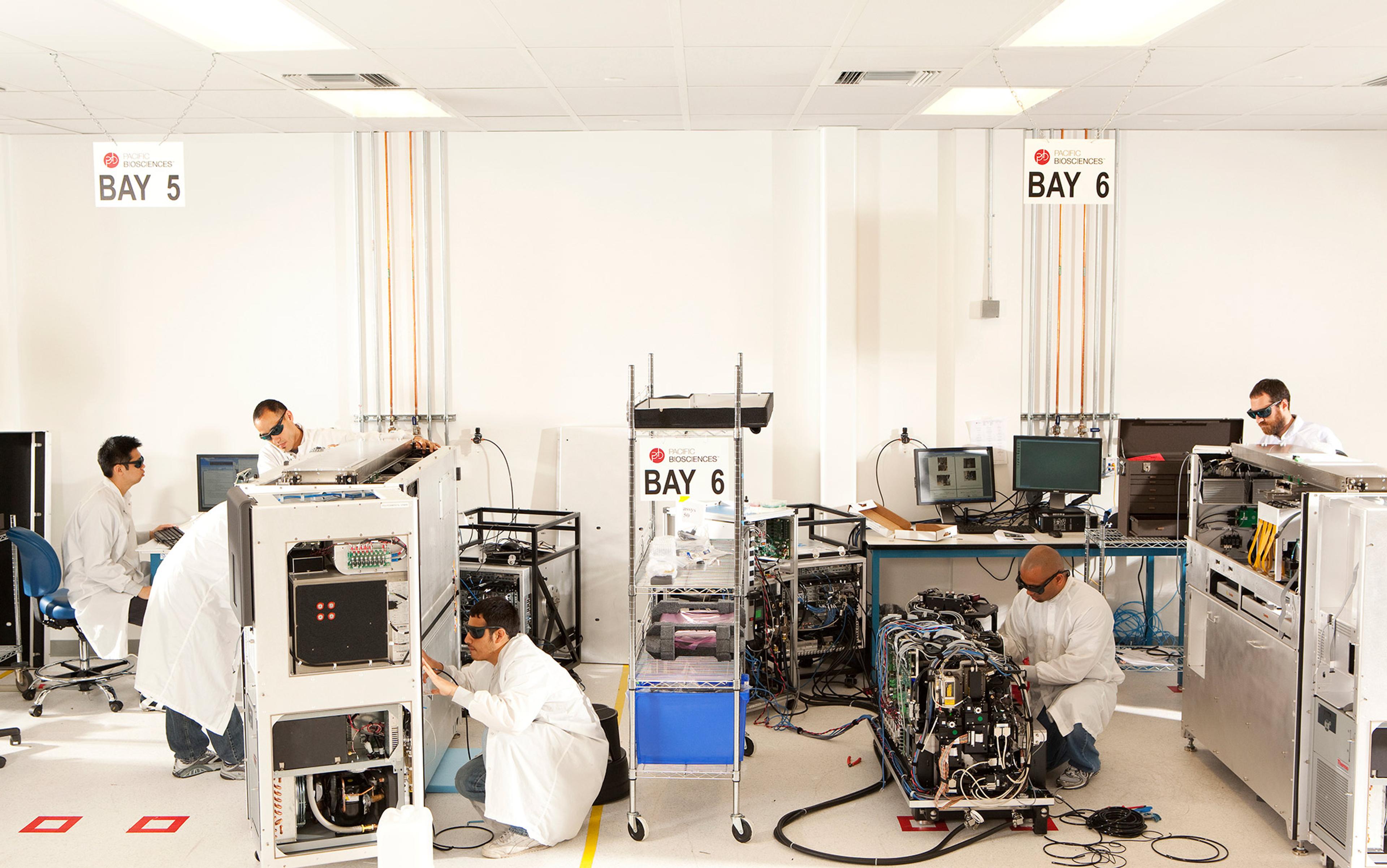

When data were analysed, this had to be done on mainframe computers located outside history departments. The production of data was even more work-intensive and based on an increased division of labour, using research assistants to read sources, as well as punch-card operators, cartographers and other specialists. This type of very hierarchical collective research was explicitly designed to follow the model of the ‘hard sciences’. Many ‘new historians’, as radicals politically opposed to Fordism, could not entirely approve this organisation. Critics of Fogel and Engerman talked about the work of ‘helots’ – from the slaves of the Spartans – in historical ‘factories’.

Some pioneering efforts of this type are still cited today: the University of Michigan study of the Florentine census of 1427 is a landmark in the history of the family. Many series, or their analyses, were never completed, however, and data were often lost in successive generations of computer formats. More generally, questions arose as to the returns on such investments.

Not incidentally, the neoliberal economic policies of the 1980s decreased funding for historical research projects in most countries. Dissertations had to make sense as readable books if one wanted to obtain a tenured position. Thus, quantification seemed less rewarding at the very moment when microcomputers allowed historians to process their own data. In fact, the ready availability of computing power diminished the value of methods adopted in part for the distinction they conferred.

Quantification in history departments did not just die quietly, however. It was also attacked for its exaggerated focus on structures and series. While ‘new social history’ had originally aimed at making ordinary (in the sense of not famous) people legitimate targets of enquiry, radical scholars were no longer satisfied with writing a history of the masses. Not only were they more and more interested in minorities, and not just the ‘average man’; they also sought to recover individual voices and agency. On the whole, most historians rejected Marxism, economic determinism, structuralism and quantification, and favoured the individual, narrative, and cultural or political dimensions of history – seeing all this as antagonistic to quantification.

From the early 1990s onward, quantitative methods courses for historians in universities mostly disappeared. Those that survive in some places are often disconnected from the rest of the curriculum, akin to foreign-language courses intended for use on a specific set of sources, as Margo Anderson put it in 2007. Economic history is mostly written in economics departments, where it is considered self-evident to reconstruct estimates of gross domestic product for periods when there were no official statistics and, in fact, no nation-states. Meanwhile, most members of history departments consider such endeavours as anachronistic and pointless (why would past GDPs matter anyway?) – if they are even aware of their existence. There is no generally agreed-upon banner for non-quantitative history: it is just a fact of academic life. Lawrence Stone did herald a ‘Revival of Narrative’ in 1979; but from the perspective of history departments, the numbers war faded in memories because of a lack of serious opponents.

For many historians today, the use of computers or numbers rather refers to ‘digital humanities’, a phrase popularised in the mid-2000s, or, in the past decade, ‘big data’. Most bearers of these flags actively ignore the existence of the ‘new historians’ of the 1960s – they would rather present their efforts as entirely novel, and they do not look for inspiration in sociology or economics, but in computer sciences or physics. Yet they have reinvented many of the old mottos: ‘retooling’ history so it functions more like the ‘hard sciences’, with more money, more teamwork, and more objectivity. Fifty years after Le Roy Ladurie, the historian-as-programmer is back, with a vengeance. When they are aware of the first wave, they consider that it failed because it came too early. Better computers and more digitised data will now allow success.

Funding agencies seem to share this view. Since the 2000s, there has been a surge of grants for anything ‘digital’ or ‘big’. This has led to massive hiring of temporary personnel to input data. Some digital humanities projects once again pretend that they will make all previous scholarship obsolete, then channel a lot of resources without producing original historical results. The Venice Time Machine project, launched in 2013, aimed to build ‘a multidimensional model of Venice and its evolution covering a period of more than 1,000 years’ by digitising kilometres of archives. It would have arguably advanced research in computer science, notably in optical character recognition, but the benefits for historical knowledge were far from clear. Perhaps predictably, the project ran into serious problems and was put on hold in 2019, but an eight-year ‘second phase’ is now advertised.

Meanwhile, David Armitage’s and Jo Guldi’s The History Manifesto (2014) went as far as to criticise the undue interest of many historians in archives, individual agency and the political stakes of identities. Among the new wave, they adopted the most martial rhetoric, accompanied by large publicity – something like a new Fogel-Engerman duo. In an essay for Aeon, commenting on the specialisation of non-data-driven historians, they wrote : ‘Why not toss all those introverted but highly competent monographs and journals articles onto a bonfire of the humanities?’

As historical data become available online, many analyse it without questioning its provenance and construction

It is striking that much of the criticism launched against the ‘big science’ of the first wave around 1980 could be repeated today without any change: lavish funding, mathematical sophistication, a quest for exhaustive data – yet very few new insights about the past. Those who marvel, for example, at Google Ngrams without pausing to wonder what exactly is included in Google Books are, for us, not very different from those who admired figures for deflated wages without questioning their sources.

The ‘digital humanities’ projects encounter the same pitfalls as the old ‘new histories’ of the 1960s did when some practitioners considered that using new techniques for data storage and analysis made source criticism optional. The new fashion for ‘bigness’ is often based on the old naive idea that many biases will cancel out one another. Archaeology as well as ancient and medieval history offer many cautionary tales in this respect. For example, Søren Michael Sindbæk, a pioneer in the careful network analysis of archaeological and narrative medieval sources, wrote that ‘“big data” is rarely good.’ This statement concludes his experiment on a large heterogeneous repository of data on maritime networks. A network visualisation of this data mostly revealed patterns in archaeological knowledge and ignorance – a useful result per se, but not to be confused with patterns in medieval transportation. Yet as historical data become more readily available online, many economists, physicists and others analyse it without questioning its provenance and construction.

We like the historian Mateusz Fafinski’s admonition that ‘historical data is not your familiar kitten. It’s a sabre-toothed tiger that will eat you and your village of data scientists for breakfast if you don’t treat it with respect.’ But we are not sure that the distribution of power across disciplines is such, for now, as to allow this type of retribution. Non-quantitative historians are not likely to win the war for interdisciplinary grants soon; nor will historians prevent practitioners from other disciplines from misinterpreting data. Yet just leaving the battlefield to find comfort by forgetting quarrels about methods in (financially) besieged history departments would not satisfy us. Outright wars on methods have been unproductive when they have entrenched boring research standards on each side of the divide. Yet there have always been exceptions – quieter hybridisations that actually produced new insights. Those are the ones that we like to lift from the shadows of less bellicose scholarship.

While others loudly advertised for purported digital revolutions, many colleagues invented productive ways to bridge the gap between humanistic and social-scientific approaches. They created diverse alliances between variants of source criticism and situated knowledges on the one hand, and quantitative, formal or data-centred methods on the other. There are many pathbreaking examples – pathbreaking because they did not coalesce into a school or subdiscipline. As early as 1978, Cissie Fairchilds used statistical techniques for an in-depth analysis of an allegedly smallish sample of archives related to illegitimate births in late-18th-century France. Her research is remarkable for her carefully discussed relabelling of relationships and social backgrounds that, in her sources, were categorised according to the laws of that time. Her aim was to bring her quantification as close as the source allowed to the lived experiences and voices of women.

In 2017, the art historian Yael Rice published a study of manuscripts of the 16th-century Mughal court. Those include not only beautiful illuminations, but also names that document the cooperation behind pictures – for example, between a designer and a colourist. Rice used these leads to uncover the operation of workshops that had left few other traces. She found a steady rotation of cooperation that might explain how an integrated courtly painting style developed.

Two women historians thus discovered, through a careful and inventive close reading of their sources, things that their predecessors had thought impossible to assess. Some of their results were produced through methods that are not taught in most graduate programmes in history (statistical tests for Fairchilds, network analysis for Rice), and that no historian could have applied on a personal computer before the late 1990s. Yet they did the job by themselves – and it was only one part of their research. Not something that obliged them to stop questioning categories, to forget individual agency or to put aside aesthetic questions. Quantitative techniques were just one tool among others that helped them do their job as humanists.

In this universe, peopled by diverse colleagues producing home recipes and bespoke formalisation, we feel politically and scientifically at home – much more so than in the world of ‘retooled’ historians. Moreover, what happens here is less boring. Using quantitative methods to demonstrate the weight of well-known structures is like beating a dead horse with a highly sophisticated bludgeon. Do we need to spend so much time and effort to collect, count and classify, if the results are predictable or expected? There are, however, different, more rewarding ways to count.

Counting always requires a decision to consider two elements as equivalent or different from one another

It is possible to use quantification at micro scales, even to assess the exceptionality of individuals and to discuss their agency. What drives quantification is the density of information and the determination to deal with it in a systematic way – rather than dealing directly with entire societies. In the 1980s, some Italian microhistorians explored the meanings of Edoardo Grendi’s phrase the ‘exceptional normal’ using quantitative techniques, and others have done so since. For example, in 2012 Paul Ocobock used the narrative of the caning of a Kenyan Asian boy to frame his examination of corporal punishment in colonial Kenya – but he wove it together with a quantitative study of court and prison records, showing which dimensions of the boy’s experience were commonplace (his age and gender) and which were exceptional (his Asian origin). Data need not consist of long, homogenous series pertaining to a single phenomenon. Intricate sets of trajectories and interactions are more interesting: patterns can be discovered thanks to techniques such as multiple correspondence analysis, network analysis or sequence analysis.

Counting always requires a decision to consider two elements as equivalent or as different from one another. Quantification uses categorised data. Yet this categorisation does not have to be done in a standard, ahistorical way or to remain blind to the intricacies of lived identities. Assigning categories such as ‘type of occupation’, gender or religion to persons on the basis of historical sources is always a scientifically tricky and politically charged operation – whether the aim is to produce percentages or write a narrative. Some quantifiers take this task seriously. A precondition for this is the acceptance of the intricacies, the biases and the silences in our sources.

Most quantifiers routinely talk about ‘cleaning’ data, implying that heterogeneity in the sources is a problem to be solved – and that solving it is a subaltern task. For us, on the contrary, building data from sources and creating categories that do not erase all complications is not just the longest and most complicated stage of research; it is also the most interesting. We teach the value, for cunning historians (a phrase coined in the context of feminist scholarship), of outliers and weirdness as well as of missing data – in short, of dirty data, stored in verbose spreadsheets. And we teach techniques of analysis developed, for example, in intersectional economics: saying that inequalities just do not add up is important; exploring how inequalities then interact is, arguably, one of the most exciting tasks in social history.

In short, the alternative quantifiers share the microhistorian Giovanni Levi’s will to avoid a passive approach to data and sources, and uninspiring positivism associated with ‘assertive, authoritarian forms of discourse’. They do not want to use adverbs such as ‘often’ or ‘generally’ without the support of precise data; but they use formalisation as an aid to intuition rather than affirmation.

Even when the numbers seem to refute conventional wisdom definitively, the investigation should not end there. Where did conventional wisdom (whether of historians or actors) come from in the first place, if the data so easily refute it? For example, Geoff Cunfer showed that the ‘Dust Bowl’ was not directly caused, as was generally believed, by indiscriminate ploughing of grassland – but, rather, by drought, which often caused similar dust storms in the late 19th century. He did not stop there, however, but explained how the scarcity of data concerning older storms and the artworks representing the ‘Dust Bowl’ had influenced former interpretations.

Numbers, when used as tools, not fetishes, allow defamiliarisation, comparison and oblique readings of sources: they can be part of an experimental practice of history that is playful, in the sense of not boring, yet attentive to ethics. Rather than limiting intuition and creativity, quantitative methods can stimulate them. Turning historical sources into data does not have to be a way to impoverish them, to erase lived experiences. Quantification or ‘digital history’ just offer new books of recipes, among others, allowing us to see sources differently and foster new interpretations. These recipes are good at making questions and categorisations explicit, at preventing us from hiding widely shared experiences and embarrassing exceptions under our interpretive carpets. They are definitely not the ultimate weapon that some still hope for, the one that could kill debate by ascertaining causation or producing definite answers.