At present, describing historians as political actors evokes bias, political manoeuvring and a lack of critical thinking. This description conjures up historians merely as political pundits, rummaging through history in search of evidence to support their own political goals and potentially falling into presentism. The past few decades have seen the rise of this hybrid profile, and while some have claimed that politicians need historians so that we can transform current political debates and use their expertise to help us project ourselves into the future, critical voices have warned that ‘rapid-fire’ superficial histories might serve political aims at the price of historical accuracy.

Therefore, defining J G A Pocock (1924-2023) both as a historian and a political actor stands in need of clarification since, arguably, he does not fit into a two-camp debate on the usefulness of history, but instead he shows how history inhabits us at a much deeper political level.

Originally published in 1975, Pocock’s book The Machiavellian Moment is an acclaimed masterpiece and one of the most influential 20th-century works for intellectual historians, political philosophers and political theorists. By 2025, it will have inspired scholars and public debates for 50 years. The Machiavellian Moment presents a fluid, non-linear and geographically diverse history of republicanism as a transatlantic political language that can travel among different periods and contexts, namely, from classical antiquity to Renaissance Florence, early modern England and colonial America.

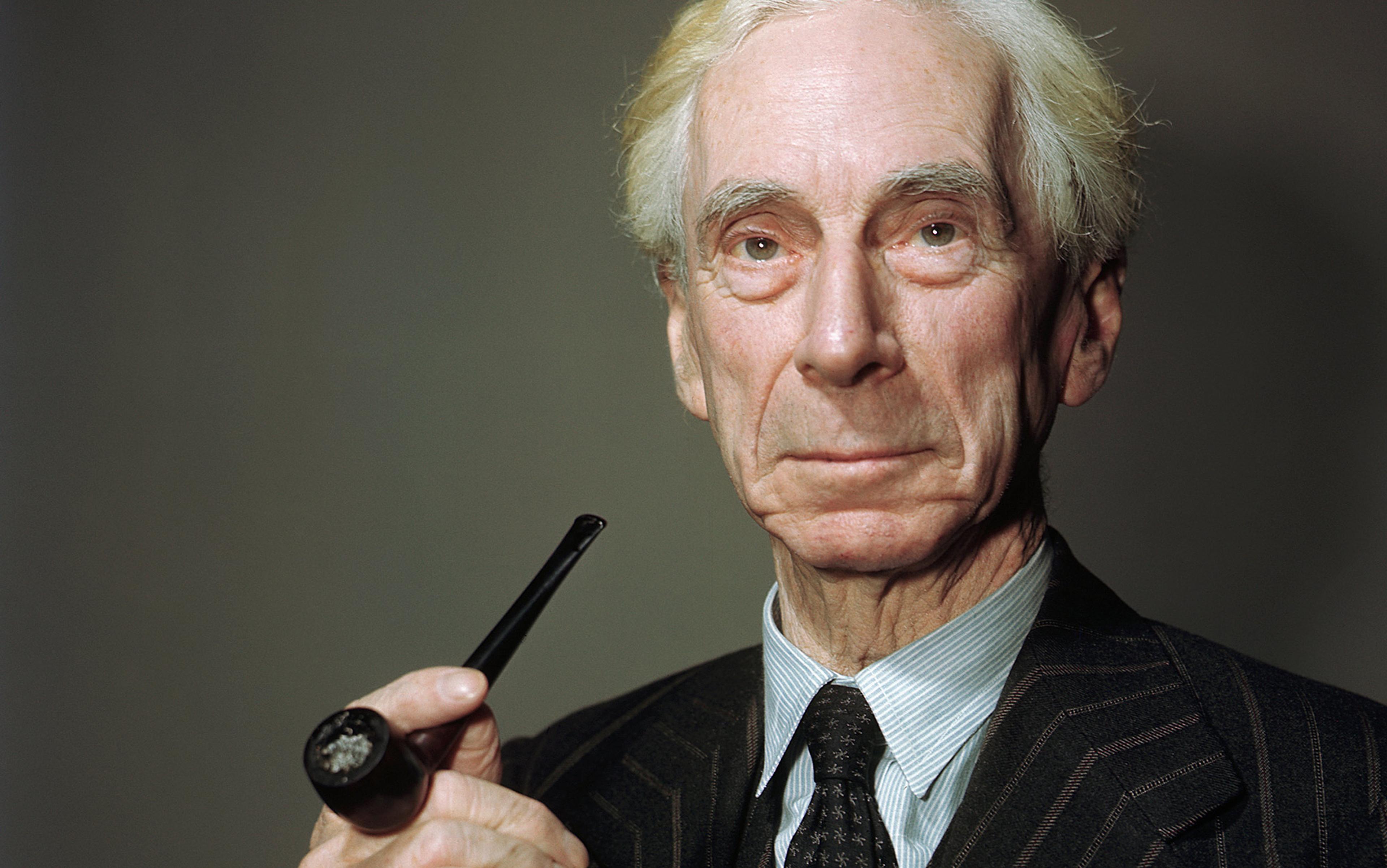

Niccolò Machiavelli (detail, 1843) by Lorenzo Bartolini, Uffizi Galleries, Florence. Courtesy Wikipedia

The book generated academic and wider public controversies, since Pocock decentred the history of the foundation of American politics when he placed the American Revolution as only an episode of an Atlantic republican tradition. In other words, he traced the intellectual origins of the foundation of the United States as far back as the ancient Aristotelian ideal of citizenship and Florentine civic humanism. In doing so, he challenged, first, the understanding that the US Declaration of Independence was a pinnacle of modernity, the deliberate and singular foundation of a polity, and, second, the view that the debates surrounding America’s foundation were coined in a liberal vocabulary. In Pocock’s interpretation, these debates were neither fully liberal nor completely unprecedented in history.

This revisionist history was, additionally, written by a London-born New Zealand expatriate living in the US. He was a citizen of the British Commonwealth whose work revised the existing narratives about a former British colony reclaiming its political identity and cultural independence. In a way, this was a familiar story, since he experienced the contestation of political identities as an integral part of the history of the British peoples and conceived of British history as the history of several nations interacting with an imperial state.

Despite its significance, Pocock’s best-known book was not originally intended for the general reader, and it is famous for its evocative style and erudite character. On the contrary, he himself acknowledged that his interlocutors were highly specialised academics. The Machiavellian Moment, he later admitted, ‘was intended to be difficult’, written in a ‘complex and discursive style’ not meant to simplify the contradictions and complexities that were present in the story he was trying to tell. Given the breadth and depth of his work, it is no wonder that the substantive conclusions argued by Pocock remain relatively opaque or misunderstood.

The Machiavellian Moment is a study of the formation and transmission of classical republican ideals in the Western world. In doing so, it offers a sweeping view of the survival of the Aristotelian concept of the good life based on active citizenship and civic virtue, and the effort to avoid corruption and political instability. Three historical moments sequence this story: Florentine Renaissance, 17th-century England, and the American Revolutionary context. Niccolò Machiavelli and James Harrington are the primary drivers of this transformation and, in terms of the conceptual constellation around which republican language revolves, concepts like time, virtue, corruption and liberty are central. Pocock shows how Machiavelli, in line with Aristotle’s concept of active and virtuous citizenship, was particularly concerned with sustaining civic virtue in a moment of instability and decay in Florence, which precisely points to the expression ‘Machiavellian moment’ as the difficulty he faced in reconciling an ideal of citizenship with the uncertain and temporal character of republics.

Two other Machiavellian moments are later framed within a republican mindset, which according to Pocock shows the persistence and coherence of this tradition over time and space. On the one hand, Harrington’s goal in The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) was the design of an ‘immortal’ English commonwealth – again trying to escape corruption and finitude – which authors inspired by Harrington later adopted in the 18th century. On the other hand, in founding the American republic, the Federalists were concerned with representative institutions, arguing that strong constitutional arrangements could save the republic from corruption. During that time, it was commerce and the rise of commercial society that posed the most significant threat, as wealth encouraged corruption. In Pocock’s account, their concern was preserving virtue and political stability, which required stopping members of society, including political representatives, from indulging in luxury, selfish passions and increasing their economic power at the expense of the public.

It was either Machiavelli or Locke who provided the philosophical underpinning for a new society

As what Pocock later called a ‘tunnel history’, The Machiavellian Moment revitalised the presence of republicanism in the history of political thought by mapping across centuries the efforts to maintain struggling republics. But it was the book’s final chapter – ‘The Americanization of Virtue’ – that had Pocock involved in most controversies. Pocock linked the American Revolution with classical republicanism as far back as Machiavelli via Harrington’s influence in Britain. He wanted to show how the language of classical republicanism was present in the nation-building efforts to guarantee popular virtue against the corruption and decay represented by commerce. Crucially, this meant that a modern US society retained early modern values, and the American Revolution, instead of marking a break with the old regime, was a chapter of European history. The Declaration and Constitution were thus not completely unprecedented, which in a way minimised their significance by partially dissolving them into longstanding political languages with roots in the old world.

George Washington (1795) by Giuseppe Ceracchi. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

In contrast to Pocock’s views, Leo Strauss and his followers, for instance, held that there were only superficial connections between republicanism and the US founding, and that the exaggerated continuity of republicanism missed the influence and inaugural character of liberalism. They contended that Pocock, in highlighting the presence of republican pasts, had left little space for liberal ideas and liberal thinkers like John Locke. Louis Hartz’s The Liberal Tradition in America (1955), under the influence of C B Macpherson, had also pictured Locke as a honorary Founding Father, and liberalism, with its defence of individualism, commerce and limited government, as providing the philosophical basis for an emerging republic. The stage was set for a debate on antithetical positions: republicanism, rooted in the paradigm of civic humanism, reason and virtue, was contrasted with liberalism, defined by possessive individualism, emerging capitalism and private passions. The virtuous citizen/patriot stood opposite to the economic man, and it was either Machiavelli or Locke who provided the philosophical underpinning for a new society.

The idea that republicanism and liberalism were mutually exclusive political traditions and languages was a historiographical as well as a political commonplace and remains a widely accepted framework for understanding political discourse even to this day. The historian David Craig has noted that Pocock’s book helped popularise, as well as problematise, a clearcut division between liberalism and republicanism. Commenting on The Machiavellian Moment a few years after its publication, Pocock acknowledged that the book ‘consistently displays republicanism as being at odds with liberalism,’ although what he wanted to convey was the existence of a complex tension between republicanism and liberalism in the minds of America’s Founding Fathers.

Particularly with his last chapter, Pocock was successful at being provocative and fuelled a debate that resonated at historiographical, cultural and political levels. Time, politics and context were intricately intertwined categories. How people understand their pasts, and the history of how they write about their pasts, have political implications and determine (not entirely but crucially) the political experience at any given time. It is historians who undertake the fundamental tasks of writing and rewriting historical narratives and, in doing so, shape present political identities. Following Pocock’s approach, history is the most powerful element in the construction and destruction of self-knowledge of political societies, and one of the engines of a shared sense of community. Pocock’s words in this regard stand out: ‘what explains the past legitimates the present and moderates the impact of the past upon it’. In other words, Pocock’s critique of a liberal past also entailed a challenge to a liberal identity. It is in this sense that history fundamentally matters and historians are political actors.

For an author who has devoted a great deal of attention to the political implications of societies’ historical imaginations, it makes sense to turn the spotlight on him and ask how The Machiavellian Moment was read politically in different contexts. This is an opportunity to contextualise Pocock’s text within a wider framework of reception and draw on some details of his professional biography – fittingly, as contextualism was a cornerstone of his own method.

The debates over the reception of The Machiavellian Moment have come to form a historiographical debate of their own. In the years following its publication, Pocock wrote several pieces addressing his numerous critics, both in the US and elsewhere. For sure, he wrote as a specialised historian, although the political implications could hardly be missed. One of them was the essay ‘The Machiavellian Moment Revisited: A Study in History and Ideology’ (1981), in which the reader gets to dive into the ideologisation of his book. Pocock provides a justification of his own approach to republicanism among different historiographical (and ideological) schools. For him, the last part of the book presented two conceptions of liberty, the ‘active-participatory’ and the ‘negative-liberal’, which were both used in the political scenario of the 18th century and at the time in which he wrote the essay. It was the coexistence of republican and liberal ideas and the possibility of using the language of republicanism that some American historians later perceived as a threat to the liberal foundational constitutionalism, that is, as a problematic rewriting of the historical narratives underpinning political discourses. Scholars on the Left like Joyce Appleby, Isaac Kramnick or John P Diggins saw Pocock’s doubt that Locke, Montesquieu and David Hume provided the basis for the Federalist papers as doubt about America’s political character and cultural identity as derived from liberal values, that is, as an alleged departure from individualism, constitutional pluralism and commercial values.

His aim was to problematise the intellectual origins of the foundational myth as exclusively liberal

America, Pocock said, became a ‘very unclassical’ republic and that is why, he contends, a foundational myth served a political purpose and had the potential of speaking to contemporaries: it was a nation, he wrote, ‘founded in experiment’, in which a covenant created a bond among individuals. According to this so-called foundationalist myth, US history and society originated thanks to a conscious and deliberate act, or rather as an act that could be separated into two moments: the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the ratification of the Constitution in 1788. The language of liberal rights, most notably articulated by Locke, served as the blueprint in this process. In this ‘foundational culture’, citizens judge the performance of the republic according to the observance of these principles. And therefore the existence of political corruption would not only mark a decadence, but also shake the very foundation of the (liberal) republic. In other words, liberalism became integral to the nation’s identity, and doubts about this correspondence amounted to attacks upon a cultural identity. What was at stake in situating either Locke or Machiavelli at the roots of US political history was Americans’ own understanding of who they were and are. In Pocock’s words in 2017, ‘in debating the fundamentals of their government, Americans debate who they essentially are.’

This debate was by no means confined to US academia. In this sense, Pocock was accused by Italian historians including Renzo Pecchioli of being an exponent of the ‘ideologia americana’. For instance, Cesare Vasoli reproached The Machiavellian Moment for being less a work of history than a work of ideology targeting the political roots of US culture. Pecchioli argued that Pocock’s interpretation pictured the US as the culmination of a republican tradition originating in Europe, and in doing so it positioned Florentine republicans as one link in the chain of a global republicanism. Reclaiming the singularity of European Renaissance republicanism, Pecchioli labelled Pocock’s history of republicanism as ‘neoliberal’, by which he meant that the global continuities described by Pocock masked instead a form of appropriating and undermining the significance of European traditions. Pocock was thus reduced to representing an ‘American liberal imperialism’ and, being unaware of his own ideological bias, he had established a liberal history of republicanism. Interestingly, the tentacles of this allegedly liberal expansionism even seized its political counterpart, republicanism. Pocock defended himself with his elegant and sharp rhetoric by showing that his Italian critics had misunderstood his conclusions, and that, quite on the contrary, the so-called republican thesis was not a strategy aimed at imposing an ideology of American liberalism onto the trajectory of European history. His aim was not to uphold American traditional liberal values, but precisely to problematise the intellectual origins of the foundational myth as exclusively liberal.

In sum, Pocock was paradoxically under attack for being too liberal, but also for not being liberal enough. Said differently, Pocock was criticised for being too American and for not being American enough – all the more intriguing for a New Zealander. In a way, these examples vividly illustrate the existence of a powerful but too simplistic correspondence between American identity and liberalism that Pocock’s Machiavellian Moment precisely challenged.

Pocock was never comfortable engaging in these debates, as he himself acknowledged. In the foreword to the French edition of The Machiavellian Moment, he wrote that the book had been ‘too successful for his own comfort’, creating a ‘vehement’ debate in a ‘confused and complicated scene’. Still, he was acutely aware that historical narratives are read differently in different contexts, since – as a historian of historiography himself – he devoted his career to situating ideas in the contexts to which they belong.

Pocock died in December 2023, a few months short of his 100th birthday. His death sparked well-deserved tributes across the world and heartfelt reflections on his legacy, with a number of academic events subsequently organised in his memory. Participating in some of them, I found that, when approaching his extensive body of work, a two-fold commonsense division emerged. On the one hand, one could look at his historical practice, that is, his studies on the history of legal and political thought and the history of historiography, where a number of monographs stand out: The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law: A Study of English Historical Thought in the Seventeenth Century (1957), The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (1975) and the six-volumes of Barbarism and Religion (1999-2015), his study of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-1788) by Edward Gibbon.

On the other hand, Pocock was also celebrated for his theoretical and methodological contributions on how to study the history of political thought, mostly spread across journal articles and essays, and many of them collected in Politics, Language, and Time (1971), Virtue, Commerce, and History (1985) and The Discovery of Islands (2005). Among those who have praised Pocock’s methodological contributions, many have emphasised the significance of the notion of ‘political language’ as an idiom, rhetoric or specialised vocabulary (such as the language of ‘common law’, ‘civil jurisprudence’ or ‘classical republicanism’). Political debates can be conducted in a variety of languages (notice the plural form), since languages could coexist with each other, be adopted by different authors and travel between discursive contexts variously located in time and place. A somewhat less discussed theoretical point in Pocock’s work is his view of the intimate link between historiography and politics, which led him to believe that histories are political narratives that should be perpetually open to discussion.

Historians narrate what was and is to be admired or despised, imitated or avoided

In the two-fold division described above, his substantive monographs and his methodological writings are typically mapped separately within Pocock’s impressive production and often presented as independent from one another. This would suggest that, depending on the reader’s interest and focus, one could engage with Pocock as a historian of political thought while possibly remaining unaware of Pocock the theorist and political actor, and vice versa. However, an interesting path (among many) into Pocock’s oeuvre involves looking at how his insights on historiography illuminate his work as a historian of early modern republicanism and the political debates surrounding the reception of The Machiavellian Moment.

I take Pocock’s extensive reflections on the role of historians in the abstract as an invitation to consider his own writings in this light: he personified, according to his own formula, a historian who is also a political actor. In this picture, expert historians are prominent public figures who are far from comfortable seclusion in so-called ivory towers. Historians occupy a central, privileged position for crafting and re-crafting shared meanings and political identities. They narrate what was and is to be admired or despised, imitated or avoided.

Pocock’s views are related but not identical to those of his close associate Quentin Skinner. In defending the importance of contextualising intellectual history, Skinner had to counter accusations of antiquarianism and address critiques about the public irrelevance of historical knowledge. Building on this defence, Skinner has shown, for example, that political freedom has been historically linked to the absence of coercion, thus highlighting that these insights could be potentially helpful when navigating present-day politics. His strategy has been to underline that the past could be put to use in the present. In doing so, he nicely articulates a defence of the role of the historian as a public intellectual who brings together past, present and future, but his point remains susceptible to the pitfalls of political punditry.

While for Skinner history can be a political tool, Pocock’s claim is that history writing is, to some extent, political in itself. Pocock’s intricate relations between history and politics crucially merges the polity and the academia, that is, political debates and academic discourses are not simply in a constant dialogue, but rather they are forms of each other. In this sense, according to Pocock, historians are not potential partisans in disguise who use and abuse historical records for political purposes. History is not to be used for political intervention, but instead we get to inhabit the history that we believe. The downside is that the historian’s role carries an almost too heavy weight, as is apparent when examining the reception of The Machiavellian Moment.

Ideas about the inseparability of history and politics run through many of Pocock’s theoretical essays. For instance, in ‘The Historian as Political Actor in Polity, Society and Academy’ (1996), republished in Political Thought and History (2008), Pocock radically asks: ‘what kind of political phenomenon is a history?’ and ‘what kinds of political reflection, or theory, may the various forms of historiography constitute?’ His replies emphasise the circularity of history writing as a political act and inevitably lead us to picture a degree of both contestation and consensus in public debates.

Contestation logically implies the existence of different narratives or positions on historical events. History has therefore shed its singular nature and embraced pluralism, which manifests in the existence of several possible ‘histories’ and ‘pasts’ – within the constraints of evidence. Pocock is far from falling into the relativist trap, by which, if anything goes, everything goes. In terms of what can be said about the past, he emphasises that histories are invented but also verified, which means they are both ‘discovered’ and ‘constructed’. In turn, the existence of multiple histories also leaves us with the possibility of upholding multiple political identities coexisting within a polity. In this regard, Pocock ends up giving competing stories about a polity a prominent place in his theory, as these stories constitute political identities, foster a sense of belonging and otherness.

He further elaborates on these ideas in the article ‘The Politics of Historiography’ (2005). The processes by which political societies ‘acquire pasts’ and ‘re-tell contested narratives’ in ‘endless’ and ‘multiple’ ways enhance citizens’ experiences. In fact, narratives form historical ‘myths’ that function to ‘uphold the continued existence’ of societies, that is, to bind them together and establish their autonomy and sovereignty. This is not to say that historians should be mere instruments of governmental propaganda (although they might have been), but rather that a degree of disagreement and pluralism is integral to both the historian’s craft and the citizen’s experience.

There was no history without politics, and no politics without a contested political identity

Pocock’s career and biography might provide some clues to further contextualise his approach. Although he moved to the US in 1966 and remained there until his death, Pocock grew up and spent most of his early life in New Zealand. He travelled between Britain and New Zealand while doing a PhD at the University of Cambridge, yet he retained his New Zealand citizenship and considered his home country to be instrumental in shaping what he called an ‘antipodean perception’ of history. The Machiavellian Moment, which he conceived during the years spanning his own transit between ‘the South Pacific Ocean’ and ‘the Mississippi Valley’, is fittingly also a history determined by the ‘voyaging’ of people and ideas. As he said in his Valedictory Lecture (1994), he had traced the ‘journeying’ of the Atlantic republican tradition. A bold statement follows, struck through by his own pen in the manuscript of this lecture, admitting that ‘only a mid-Pacific being … can truly develop a mid-Atlantic perspective’.

Being part of a family of settler descent, histories were naturally in motion, determined by ‘voyagings’ and generated by settlements and contacts. British history, which for him included the American Revolution, was a global phenomenon with locations in two hemispheres. And, as far as we accept that histories and political identities are inseparable, a sense of political contestation easily arises from a contested history. When thinking of history as the creation of autonomy, sovereignty and political identity, history writing sets the scene for a ‘contest for power’ in a postcolonial world. Both hegemonic and ‘subaltern’ (ie, subordinated) positions generated non-final histories that were never quite settled and were required to find ways to enter into a respectful dialogue. It is with these theoretical points in mind that I suggest framing the controversies generated by The Machiavellian Moment. The insistence among many American academics in reading Pocock’s work as a challenge to US history and identity was artificial from the perspective of a historian like Pocock who was ‘never quite at home’ and who had personally witnessed the struggles that configurate the political identities of the ‘British peoples’. For Pocock, there was no history without politics, and no politics without a contested political identity.

While attempting to read Pocock’s own career and contributions to the history of political thought as part of contemporary political debates, I am purposely avoiding simplistic definitions about his political sign in present-day terms. Many critics understood that The Machiavellian Moment was an attack of contemporary liberalism per se, but in fact his belief in the inherent contestability of histories accordingly required a robust pluralism and organic liberalism. Allowing different and sometimes opposite points of view was, he argued, a necessary condition for the historical profession to take place. To put it differently, the historical profession, as Pocock envisaged it, required a liberal political setting: ‘History is a field of study in which many explanations can, and must, exist together.’ (My emphasis.) In a sense, all history writing enables the creation of multiple worlds and facilitates a constant redefinition of the continuities and discontinuities that link past, present and future.