Polio should have been eradicated long ago, at least in the developed world. After all, we’ve had a good, efficient vaccine for 60 years. So why is polio still here? And what is it doing in my country?

Israel is the original start-up nation, powered by high-tech and science, with some of the most sophisticated medical research in the world. We have come a long way from the 1950s, when polio was still with us and the signature experience was living on a Kibbutz. We are a modern, wired nation, but we forgot one thing: we still live in the Middle East. We have great weather, plenty of sunshine, lovely beaches, and two relatively nearby countries – Pakistan and Afghanistan – where the wild polio virus still roams free.

Shortly before polio returned to Israel, it hit the sewers of Egypt, our neighbour to the south, in December 2012. Egypt, like Israel, already vaccinated widely – so someone from Pakistan must have entered Egypt, used a toilet, and excreted polio into the sewer system around Cairo, probably infecting some Egyptians along the way. Egyptian physicians could find no cases of polio paralysis, the most devastating outcome of the disease, and that made sense: 95 per cent of people infected with polio show no symptoms and never become sick. But Egypt knew paralysis would be next if the virus was allowed to spread. So Egypt fought back. A nationwide campaign was initiated, and more than 14 million Egyptian children were vaccinated against polio. Within a month, the Egyptians had vanquished polio from its sewers and its country, yet again.

But that didn’t stop the polio virus from migrating, to us. Pakistan and Israel don’t share a border, but travel between Egypt and Israel is a common affair. During the month it took Egypt to stop the spread of polio, someone from Egypt must have travelled to Israel, bringing polio with them.

That must explain why, on 9 April 2013, our nationwide monitoring team isolated wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) – genetically related to the polio from Pakistan and Egypt – from sewage samples taken in Rahat, a city in southern Israel. Immunisation levels in Rahat, at 94 per cent, were good but not perfect. So the Israel Ministry of Health initiated a catch-up programme in the area where the samples were collected, finding the unprotected and inoculating them with the standard polio vaccine – IVP, or inactivated polio vaccine. That product, injected through the skin, is a totally dead version of the polio virus, and cannot cause the disease.

But it was too little, too late. A few days later we found polio virus in the sewers of Be’er Sheva, a city of some 200,000 people, about 20 km south of Rahat. Our national monitors responded by increasing sewer surveillance and scrutinising the population for signs of active illness, including paralysis and meningitis, a swelling of the lining of the brain.

I was, at the time, an intern in public health at the Carmel Medical Center, in a suburb of Haifa, and I was pretty excited – it’s not every day we have a forgotten epidemic on our hands. Perhaps I was cavalier, but only because I felt sure we would contain the epidemic in a month without incident, just like the Egyptians.

It was hard to tear myself away for a long-planned family vacation to the UK while this uproar was going on. But we had a great trip, and my two kids loved both the country and the fact that their mother stopped talking about polio all day.

I expected to return to work at the hospital, business as usual, problem solved. But while we were away, polio had spread through the nation’s sewer system and Israel had spiralled into panic mode.

It was terrifying. Poliomyelitis has been with us for thousands of years, at least since the days of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs. Back then, the disease was truly rare. That’s because people were exposed to poliovirus (which spreads through faeces) as infants, and built immunity against it from the start. But with improvements in hygiene over the centuries, encounters with the virus were delayed. Without early resistance, we became more vulnerable, and a scarce disease became an epidemic.

By the first half of the 20th century, with dramatic improvements in hygiene, the ravages of polio had become well-known: infection provoked a fever, sore throat, sometimes a stiff neck. Then the terror: a so-called ‘flaccid’ paralysis, caused by lack of muscle tone, starting from the feet and progressing up, as patients became unable to walk, sit erect and, finally, breathe.

Those patients were put in ‘iron lungs’, a machine that pulls the chest wall up and down, compensating for the paralysed diaphragm and chest muscles. That was the only way they could survive. Sick children had to stay in the iron lungs until the paralysis withdrew and their muscles returned to the normal strength. For some children, it meant just a few painful months. For others, it meant staying in those machines for the rest of their lives.

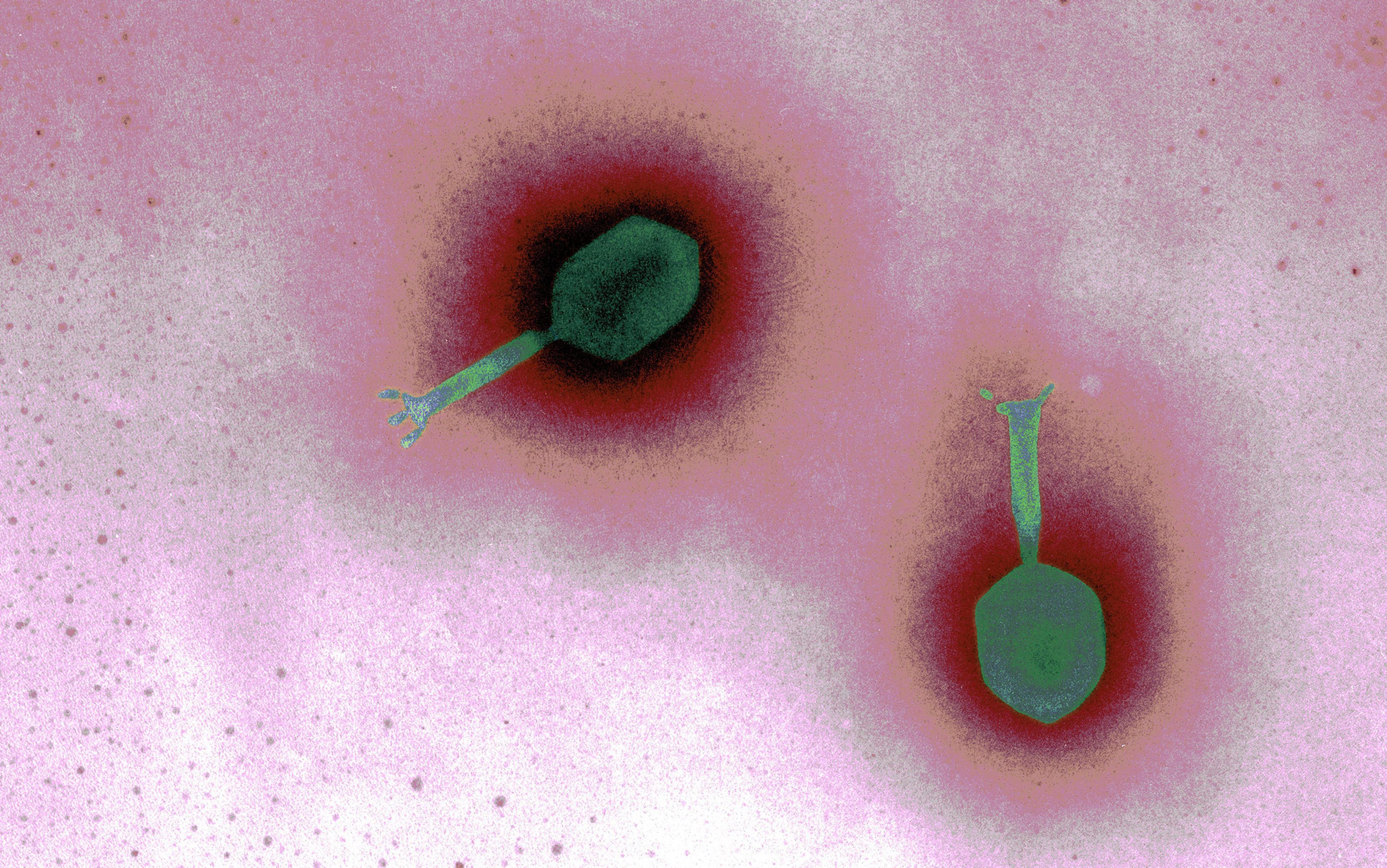

Then two people saved the world – the American virologists Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin. In the 1950s, they developed two different vaccines against polio, both efficient, both pretty safe, and both with the potential to prevent future epidemics. First, Salk invented IPV, the inactivated polio vaccine, made from dead virus. It could never cause the disease itself, but because it was injected into the muscles, it had one slight drawback: it was metabolised before reaching the gut, and thus recipients exposed to polio could harbour the virus in their intestines without ever getting sick. Such carriers could still pass on polio, through their faeces, to other carriers, and cause the disease in anyone who was not vaccinated.

Within two months, there were 15 new paralytic cases in Israel – the elderly, the immune-compromised, the already sick

Given that risk, by 1961, much of the developed world including Israel and the US switched to Sabin’s OPV, or oral polio vaccine. OPV was a living virus, weakened in the lab so it would not cause disease. Yet OPV wasn’t perfect, either. That weakened virus could still paralyse one in every 2.7 million children given the vaccine. It was better than the statistics of 1 in 200 unvaccinated children exposed to the wild virus, but still a slight risk. This type of polio disease was called vaccine-associated polio paralysis, or VAPP.

In countries that vaccinated, these life-saving but imperfect vaccines set the stage for polio’s ebbs, flows and outright outbreaks for years. It was possible to use only IVP, only OVP, or a combination of the two, with strategies varying around the world. It came home to roost in Israel in 1988, after the Ministry of Health decided to halt use of the live vaccine (and risk of dreaded VAPP) in two northern districts – Hadera and Ramla, near the city of Haifa. This group of children received only IPV, the killed vaccine, and they were well-protected against polio, though without gut immunity. Yet the switch had been a big mistake. Within two months, there were 15 new paralytic cases in Israel consisting of the most vulnerable targets – the elderly, the immune-compromised, the already sick.

Analysing the situation, the Israeli government looked at the global data collected by the World Health Organization: it turned out that in nations at risk, a combination of the two vaccines could work best. A single, previous IPV shot made of dead virus could protect against the spread of vaccine-associated polio from the live vaccine. The live vaccine, meanwhile, would prevent the virus from taking root in the gut, where it might spread out to infect the vulnerable and exposed.

So in 1990, Israel initiated a new vaccination programme – every child first received IPV, injected and dead. Then, only afterwards, they received OPV, the living oral vaccine that passed through the gut. For 15 years we saw no sign of polio in Israel – not even in the sewers. With polio seemingly gone, we followed the lead of the US in 2005 and once more pulled OPV, eliminating even a minuscule risk of VAPP.

By 2013, it was as if we had taken a time machine back to 1988 – only now, instead of just two districts, children age nine and under from all over Israel lacked gut immunity. With polio entering the country from countries around the Middle East, these kids could become carriers, spreading the virus to the unvaccinated and the immune-compromised alike, without ever getting sick themselves.

Just as before, such children endangered everyone with whom they came into contact. We found the polio that they carried in sewers all over Israel, and it was only a matter of time before one of them infected a vulnerable neighbour or relative – elderly grandparents; HIV patients; transplant or autoimmune patients on immune-suppressants; perhaps babies who hadn’t yet been vaccinated or developed antibodies. The government determined that a supplementary dose of OPV for carrier children was the only way out.

The vaccination campaign began on 5 August 2013, and Facebook exploded with complaints over the sacrifice that meant: totally healthy children were to receive the live vaccine, and parents were livid.

Fanning the flames of anger and fear and sabotaging our campaign was anti-vaccine propaganda coming from around the world, especially from the US. It’s amazing that this uneducated movement would descend on Israel in the middle of our crisis, convincing our population to turn OPV down. They doubted OPV efficiency and safety. They questioned the motives of the Israeli government and, alarmingly, they dismissed the existence of polio as an infectious disease.

We had to convince people with healthy children to vaccinate them again, not for their own safety, but for the public good

Now the war to stop polio was being fought on two fronts – vaccines and words. The vaccines did their part. Children who took those OPV drops built their gut immunity against polio and were no longer at risk of becoming walking biological weapons. If a child was already a polio carrier, the OPV wouldn’t help, but it wouldn’t harm him or her either. If the kid wasn’t a carrier, the OPV would make sure he or she would never become one.

But that wasn’t enough. We had to convince people with healthy children to vaccinate them again, not for their own safety, but for the public good. As a student of public health and a blogger with a social media presence, I took to the internet, especially Facebook, to fend off the anti-vaxxers, answer these questions, and explain the facts. It was such an all-consuming job that my kids and friends didn’t get a chance to see me for the next two months.

When one question was answered, another followed, and when all questions were answered, vaccine sceptics went back to square one and started the whole discussion again.

In fact, I explained to my online audience, for those not receiving the dead vaccine first, OVP did bring a small risk of VAPP – but that wasn’t the situation now. Everyone getting OPV had gotten IPV first.

I must be a part of the ‘Big Pharma’ industry if I thought polio was a dangerous disease, they said, or just a fool

Every time I set the record straight, pushback emerged. But after a while, I found a whole community of helpers by my side, waging the battle at the online front. Israeli doctors, science bloggers, the sceptics community and scientists all joined the explanatory effort. The data about the vaccine was available and most of us had lots of experience at explaining science in simple terms.

For months, the firestorm raged.

‘Since no one is sick, why should we vaccinate?’ asked the anti-vaxxers.

‘Why do you want to see someone with polio paralysis?’ asked the pro-vaccines community.

‘Why should I put my child at risk?’ asked a parent.

‘You’re not putting your child at risk,’ responded the pro-vaccines groups. ‘Getting OPV after IPV is completely safe.’

Pro-vaccine parents published pictures of their kids receiving OPV in the nurses’ clinic to prove their point.

As my online presence increased, I was personally targeted by anti-vaccine activists. They questioned my professionalism as well as my personal integrity. I must be a part of the ‘Big Pharma’ industry if I thought polio was a dangerous disease, they said, or just a fool.

As long as the accusations stayed virtual, it was all right, but I was terrified that someone might find out where I lived and attack my family. I went offline for a few days. Luckily for me, by that time my pro-vaccine colleagues were deftly handling the onslaught. They kept on the whole time I was gone. After I came back, we started a vacation rotation. Each time someone else went offline, others stayed on to fight the fight on Facebook, convincing parents to vaccinate their kids.

Every day during those two hard months, there was a different obstacle to tackle. One day a mother claimed her little girl had become paralysed half an hour after receiving OPV. Within minutes, the story spread through the web. Another two hours passed before someone reported the real story: the child fell asleep outside the doctor’s office, wet herself in her sleep and, when she woke up, her feet felt numb. The explanation was mundane and didn’t fit the anti-vaxxers’ agenda. The pro-vaccine group had to spread the rest of the story wherever they could.

At least I wasn’t the vaccine ‘poster girl’ anymore; there were many other people whose reputation was dragged through the mud by the anti-vaxxers along with mine. I made many new friends and, as the saying goes, a sorrow shared is a sorrow halved.

By October 2013, Israel’s official national campaign was over. The virus was still around, but more than 60 per cent of children in Israel had received OPV. It wasn’t a perfect score, but it was enough to turn the tide. By November 2013, Israel’s sewage samples started to come back negative for polio.

And in January 2014 we had a victory on the ground – a new committee convened and, after reviewing the evidence, decided to reintroduce OPV into Israel’s vaccination schedule for good.

I know this vaccine is alive, but I am not afraid. Data from around the world and from Israel tells me that OPV given after IPV is safe and effective. I know that VAPP is no longer a risk, and that the protection against polio is optimal.

We won the fight against polio in Israel but we are losing it in the rest of the world. Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria still have polio, and they are still exporting it to other countries. Syria had 22 paralytic polio cases in the wake of the civil war and the breakdown of their health system. Polio exported from Nigeria has reached the Horn of Africa, and more than 190 children were diagnosed with polio paralysis in 2013.

My parents gave me a world without smallpox – I wanted to give my children a world without polio but, beyond the borders of our little country, polio is back.